Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Take our Insights reader feedback survey

Help shape the future of ANAO Insights by taking our reader feedback survey.

Auditing Regulatory Activities

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The purpose of Insights: Audit Practice is to explain ANAO methodologies to help entities prepare for an ANAO audit.

Audit Practice: Auditing Regulatory Activities is intended for senior management and those responsible for managing internal audit within Australian Government entities that have a regulatory function.

Introduction

Regulation is any rule endorsed by government where there is an expectation of compliance. The Department of Finance describes the purpose of regulation is to provide equitable access to public services, promote competitive markets, ensure systems work effectively, and protect Australia and its people from harm. Regulatory functions may include administering (for example, providing approvals, making operational rules about, handling complaints on), monitoring, promoting compliance with and enforcing regulation.

Regulatory functions are exercised across a range of governance arrangements and structures. They may be located within Commonwealth entities that also hold responsibility for other non-regulatory functions, and that are not publicly identifiable in their own right as a regulator.

Performance audit topics on regulatory activities

The Auditor-General for Australia is an independent officer of the Parliament, supported by the ANAO, with responsibility under the Auditor-General Act 1997 (Auditor-General Act) for auditing Commonwealth entities and reporting to the Australian Parliament. The Auditor-General cannot be directed in deciding what to audit, but the Auditor-General is to have regard to the audit priorities of the Parliament.

The ANAO’s performance audit activities involve the independent and objective assessment of all or part of an entity’s operations and administrative support systems. This includes auditing regulatory activities. More information on the overall performance audit process is outlined in the Insights publication Audit Practice: Performance Audit Process.

To help explain how the ANAO undertakes performance audits of regulatory activities, this edition of Audit Practice refers to audits from 2023–24. In 2023–24, the ANAO undertook five performance audits specifically focused on regulatory functions and activities.

- Auditor-General Report No.3 of 2023–24 Management of Non-Compliance with the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 for Unapproved Therapeutic Goods;

- Auditor-General Report No.5 of 2023–24 Trade Measurement Compliance Activities;

- Auditor-General Report No.8 of 2023–24 Design and Early Implementation of Residential Aged Care Reforms;

- Auditor-General Report No.15 of 2023–24 Australian Taxation Office’s Management and Oversight of Fraud Control Arrangements for the Goods and Services Tax; and

- Auditor-General Report No.26 of 2023–24 Department of Home Affairs’ Regulation of Migration Agents.

When deciding to undertake a performance audit, the Auditor-General is guided by six key considerations: risk; impact; importance (to the Parliament and to stakeholders); materiality; auditability; and previous coverage.One of the 2023–24 topics, Department of Home Affairs’ Regulation of Migration Agents, was identified as a priority of the Parliament for 2023–24 by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit.

Specific regulatory considerations and risk areas were also considered by the Auditor-General when deciding to undertake the five performance audits on regulatory activities for 2023–24: risk-based compliance strategies; proportionate responses to non-compliance; monitoring and reporting on compliance activities; and probity in the administration of regulatory functions.

Audit approach for regulatory audits

Audit objective

For each regulatory audit, the Auditor-General decided on an audit objective, which is the ultimate question to be answered by the audit report. Audit objectives can focus on economy; efficiency; effectiveness; ethics; and legislative and policy compliance. All five of the regulatory audits in 2023–24 focused on effectiveness.

- For four audits, the objective was whether the regulator was effective in managing or administering its regulatory functions.

- For one audit, the objective was whether the design and implementation of new regulations had been effective.

Audit criteria

To conclude against the audit objectives set for each audit, the Auditor-General established a set of audit criteria and sub-criteria. The criteria and sub-criteria break down the audit into a series of smaller questions that are mutually exclusive (i.e. do not overlap) and collectively exhaustive (i.e. address the entire audit objective).

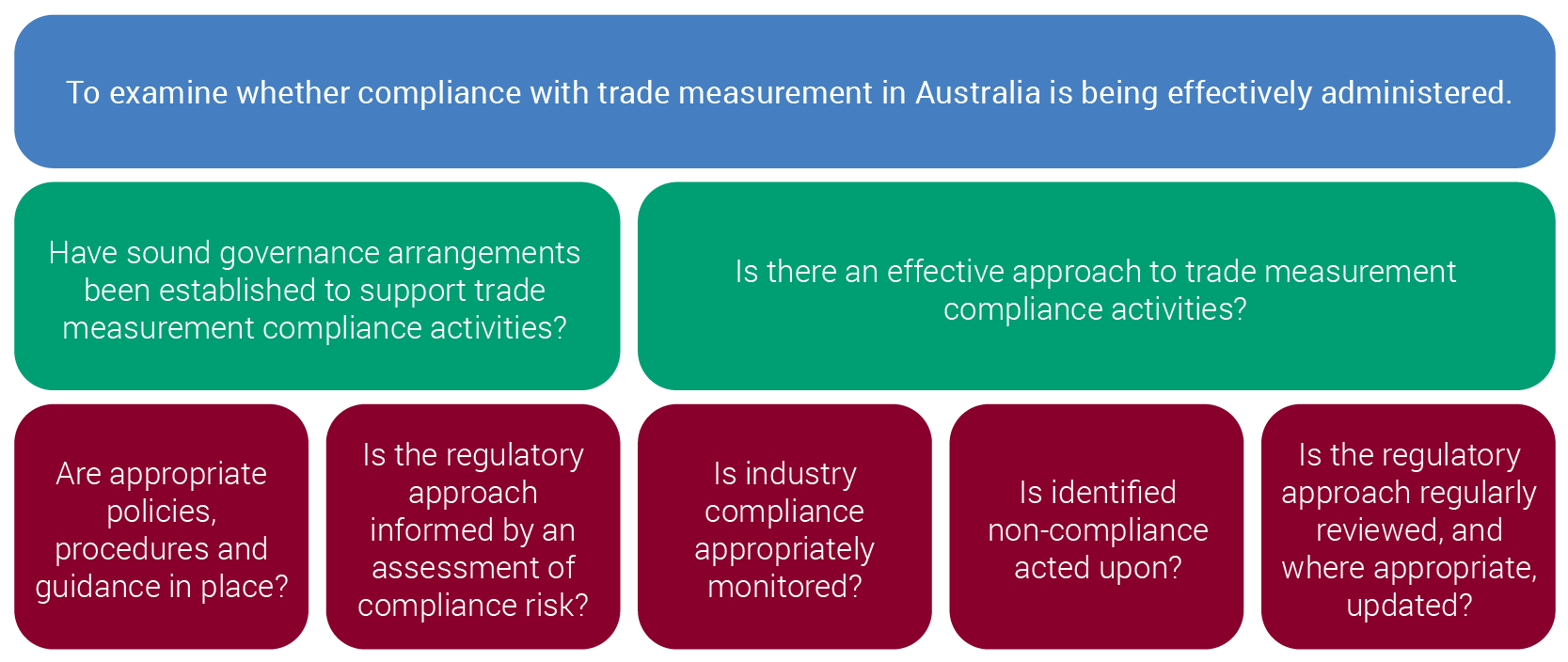

Example of audit objective, criteria and sub-criteria for a regulatory audit: Trade Measurement Compliance Activities

Source: Auditor-General Report No.5 2023–24 Trade Measurement Compliance Activities

A section in the background chapter of each ANAO performance audit report titled ‘Audit approach’ details the audit objective, criteria, and scope. Sub-criteria form the basis of the sub-headings within the report chapters.

Audit scope

The audit scope describes the period being audited and what elements of the activity or program have been included or excluded. The types of regulatory activities within scope across the five regulatory audits are outlined in the table below.

Types of regulatory activities within scope, by audit

|

|

Preparing to regulate |

Risk-based compliance approach |

Identifying non-compliance or fraud |

Preventing non-compliance or fraud |

Responding to non-compliance or fraud |

Monitoring and reporting on performance |

|

Design and Early Implementation of Residential Aged Care Reforms |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

Management of Non-Compliance with the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 for Unapproved Therapeutic Goods |

|

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

ATO’s Management and Oversight of Fraud Control Arrangements for the Goods and Services Tax |

|

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

|

Source: ANAO analysis of regulatory audit reports, 2023–24.

Evidence gathering and analysis for regulatory audits

Standards, frameworks and guidance applicable to regulators

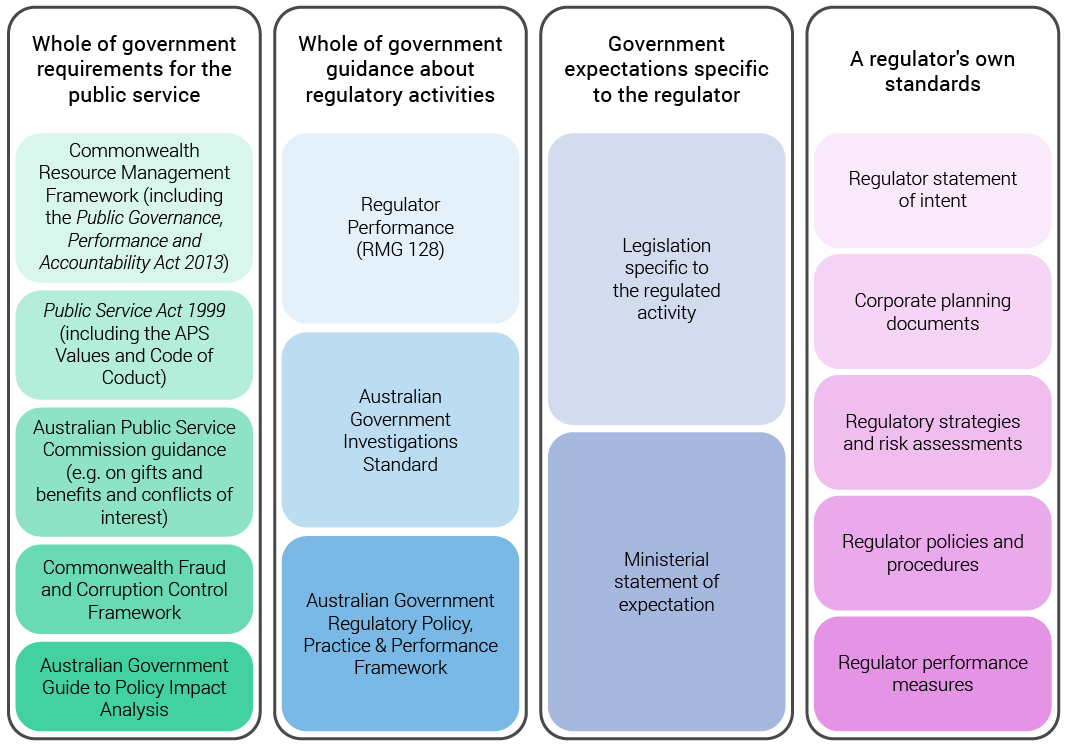

The choice of audit criteria and sub-criteria, and the analysis that underpinned answers to these questions, were informed by reference to standards, frameworks and whole of government guidance that apply to regulation and provide an objective basis for assessment. In this way, the ANAO assessed what was being done against a suitable benchmark.

In its 2025 report on the inquiry into the administration of Commonwealth regulations, the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) noted that Finance had advised the committee that a ‘Regulator Maturity Model’ was expected to be released in March 2025, which would provide ‘a road map for Commonwealth regulators to take steps towards best practice by supporting them to evaluate and improve their capability at the entity level … ‘.Paragraphs 5.19 to 5.24 of the JCPAA inquiry report provide commentary on the whole of government principles-based guidance issued by the Department of Finance.

Testing and analysis against standards, frameworks and guidance

Whole of government requirements for the public service

Australian government regulators are subject to whole of government requirements that apply across the public sector. This includes the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework, which governs how officials in the Commonwealth public sector use and manage public resources and includes requirements under the:

- Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act);

- Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule); and

- Department of Finance guidance on performance reporting, governance and risk.

The five 2023–24 performance audits on regulatory activities used whole of government policies and guidelines to inform audit testing.

|

Whole of government requirements for performance reporting |

|

The PGPA Act and PGPA Rule require accountable authorities to measure their entities’ performance.The PGPA Rule requires that an entity’s corporate plan include details of how an entity’s performance will be measured and assessed through performance measures and targets.The PGPA Rule sets out the requirements for performance measures, including, among other things, that they: relate directly to one or more of the entity’s purposes or key activities; include measures of the entity’s outputs, efficiency and effectiveness; and provide a basis for an assessment of the entity’s performance over time. The ANAO applied these requirements in regulatory audits in 2023–24.

|

Requirements under the Public Service Act 1999 (including the APS Values and Code of Conduct) and guidance from the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) on managing gifts and benefits and conflicts of interest also apply to regulators, which may have unique risks stemming from their regulatory function — such as regulatory capture.

|

Whole of government requirements for managing conflicts of interest |

|

The APS Code of Conduct, which is set out in section 13 of the Public Service Act 1999, requires that APS employees take reasonable steps to avoid any real or apparent conflict of interest. Where conflicts cannot be avoided, the APS Code of Conduct, section 29 of the PGPA Act, and section 16 of the PGPA Rule require that employees must disclose details of any material personal interest. The APSC guide APS Values and Code of Conduct in Practice states that entities may choose to require written declarations of interest of employees at particular risk of conflict of interest, such as those involved in ‘regulating individual or business activities’.Management of conflicts of interest was examined in the following 2023–24 performance audit on regulation.

Management of conflicts of interest has also been the focus of other recent performance audits involving regulators.

|

Another example of whole of government policies and guidance that were used as standards and benchmarks in regulatory audits is the Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework.

|

Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework |

|

The requirements for Australian Government entities to have fraud control arrangements in place are contained in the Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework (the Framework), developed under the PGPA Act. The Framework comprises three tiered documents, section 10 of the PGPA Rule 2014, the Commonwealth Fraud Control Policy (the fraud policy) and Preventing, detecting and dealing with fraud (RMG 201) (the fraud guidance), with different requirements for corporate and non-corporate Commonwealth entities.

|

Whole of government guidance about regulatory activities

The 2023–24 performance audits on regulatory activities commonly referenced Regulator Performance (Resource Management Guide 128), as it lists hallmarks of accepted best practice for Australian Government regulators. RMG 128 defines regulatory functions; sets out reporting requirements against the three principles of regulator best practice; and provides information on issuing and refreshing Ministerial Statements of Expectations and responding Regulator Statements of Intent.

The Australian Government Regulatory Policy, Practice & Performance Framework was published in August 2024 (after the 2023–24 audits described here), and is another important framework referenced in more recent ANAO audits of regulatory activities. The framework provides regulators and regulatory policymakers with six principles of fit-for-purpose regulation:

- targeted and risk-based;

- integrated in existing systems;

- user-centred;

- evidence-based and data-driven;

- reflective of the digital era; and

- continuously improved and outcomes-focused.

The Department of Finance describes RMG 128 as one resource that supports policy makers and regulators to achieve the Australian Government Regulatory Policy, Practice & Performance Framework’s purpose and six principles for regulatory systems.

|

Regulator Performance (Resource Management Guide 128) |

|

Using a risk-based approach in areas such as operational policy development, administration, compliance and enforcement is one of three principles set out in Regulator Performance (RMG 128). This better practice guidance was cited by three of the five 2023–24 performance audits focused on regulation. These contained a specific sub-criterion that examined whether regulators had a regulatory approach informed by risk:

|

Another whole of government policy that was used as a standard in regulatory audits in 2023–24 is the Australian Government Investigations Standard.

|

Australian Government Investigations Standard |

|

The Australian Government Investigations Standard (AGIS) is an Australian Government policy that establishes the foundational standard for Australian Government entities conducting administrative, civil, or criminal (type) investigations.

|

Government expectations

As each regulator is established to meet specific regulatory objectives, the audits also needed to use frameworks relevant to the specific circumstances of the regulator. Parliament articulates specific expectations for regulatory activities in the regulator’s enabling legislation or administered legislation; these should be read in the context of general principles of administrative law. The Executive Government sets out its specific expectations in a ministerial statement of expectations.

|

Statutory requirements |

|

The Migration Act 1958 and Migration Agents Regulations 1998 set out statutory requirements for the registration of migration agents.

|

A regulator’s own frameworks

The ANAO also had regard to a regulator’s articulation of its own context, organisation, methods of operating, performance measures and desired regulatory outcomes. These were contained in regulator statements of intent, corporate planning documents, annual reports and published regulatory strategies.

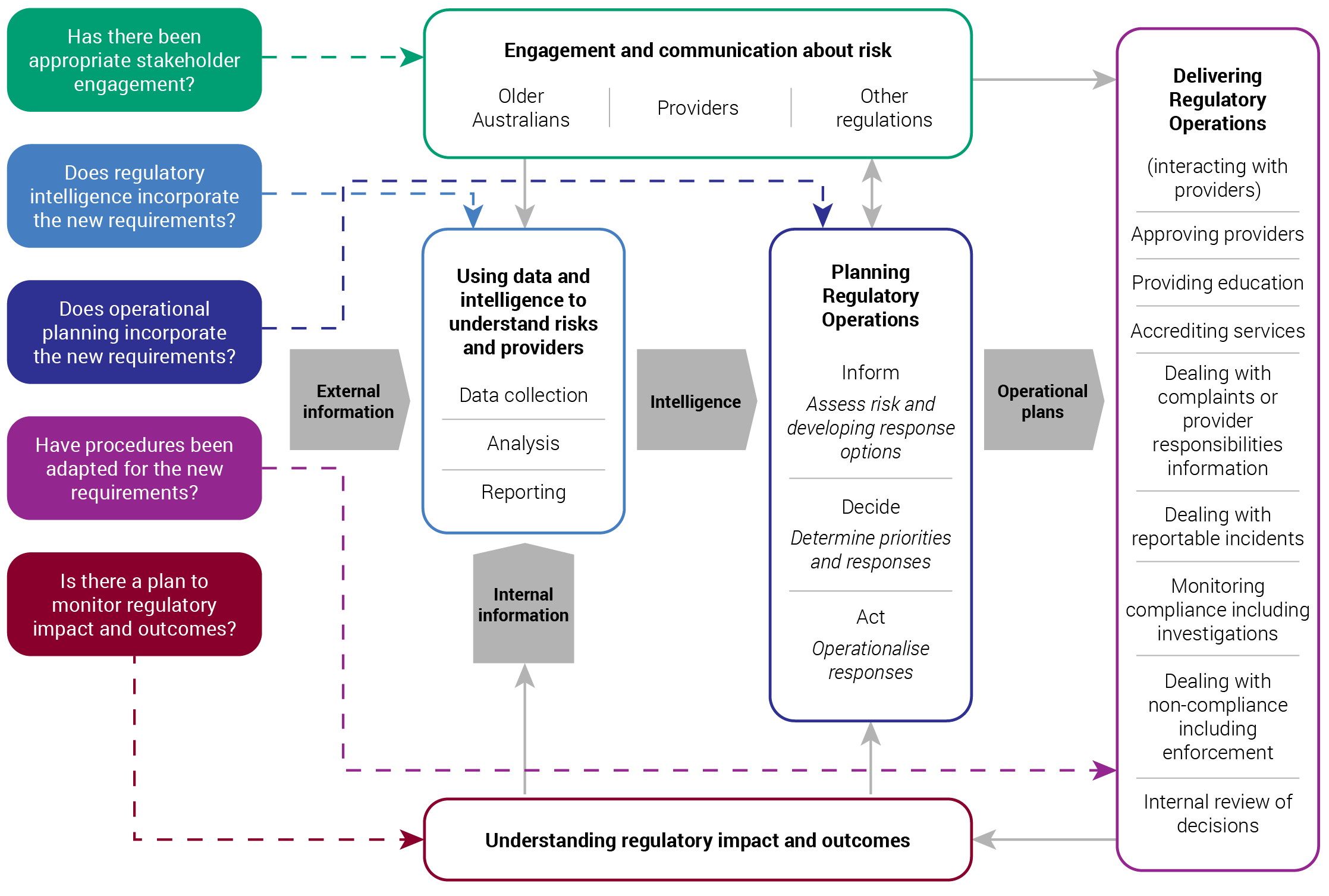

For example, the audit report, Design and Early Implementation of Residential Aged Care Reforms, assessed whether the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission (ACQSC) had adequately prepared its regulatory operations for the introduction of a new regulatory requirement. Five of the six sub-criteria assessed in Chapter 4 of the audit corresponded to the ACQSC’s regulatory operating model as it appeared it the ACQSC’s 2023–24 Corporate Plan. The audit examined whether ACQSC had made necessary changes to its operations in each of these five areas.

Example of using corporate plan information to inform audit sub-criteria: Design and Early Implementation of Residential Aged Care Reforms

Source: ANAO, derived from Auditor-General Report No.8 of 2023–24 Design and Early Implementation of Residential Aged Care Reforms and Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, Corporate Plan 2023–24, ACQSC, Canberra, p. 29.

The five sub-criteria were also applied to the Department of Health and Aged Care, which was conducting complementary regulatory activities under the same legislation with the same regulated population. A sixth sub-criteria examined whether the department and ACQSC had clearly defined their respective roles and responsibilities.

|

Assessing a regulator against its own policy and procedure |

|

The ANAO assesses regulators against their own policies and procedures.

|

Test program

For each of the regulatory audits, the audit team prepared an audit test program that outlined for each criterion and sub-criterion:

- the standards, frameworks and guidance that applied to regulators;

- the audit methodologies to be used and the evidence to be gathered;

- the testing needed to analyse the evidence and any samples to be undertaken;

- how the evidence and analysis would be used to answer the sub-criteria and conclude against the audit objective.

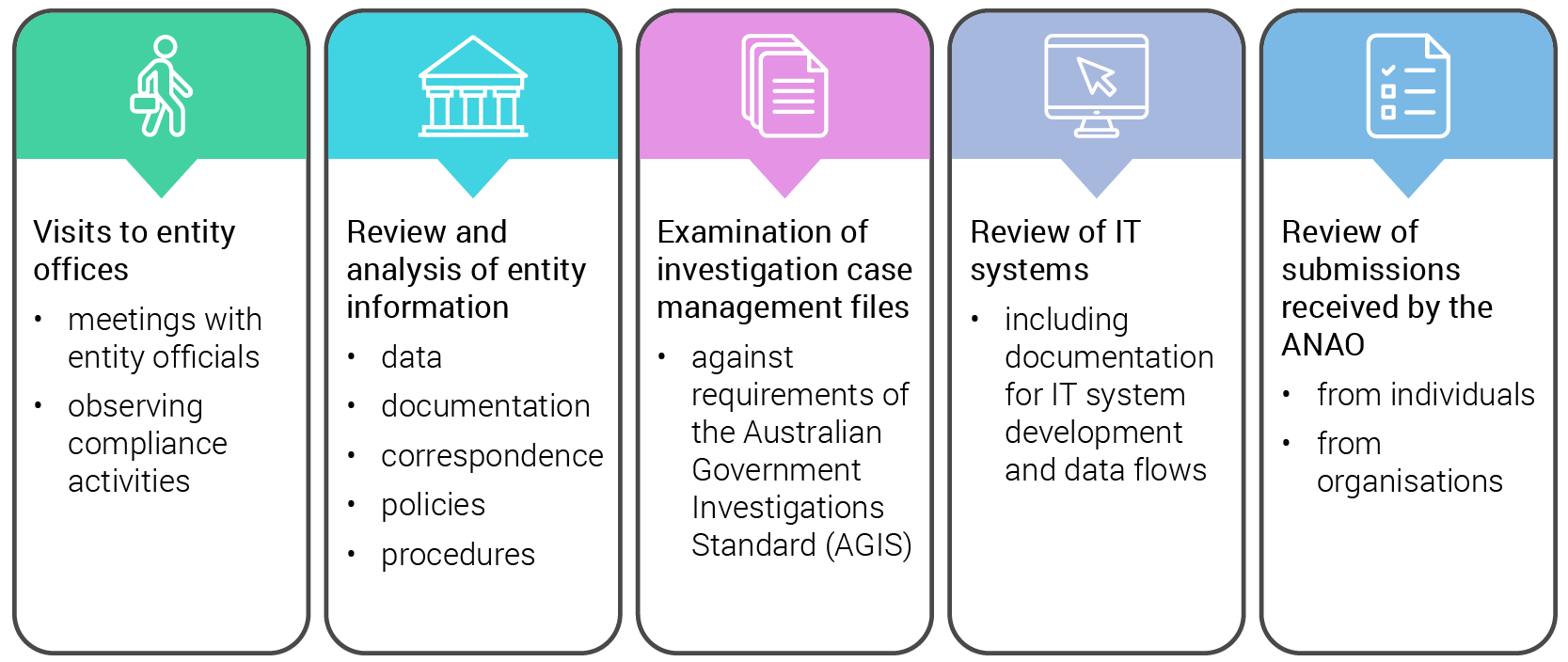

Audit methodologies and evidence gathering

The ANAO collects, reviews and analyses evidence in a number of different ways. The audit methodologies used and types of evidence collected across the five regulatory audits included:

Concluding against the audit objective and reporting

Once documentation and evidence had been gathered and analysed, the ANAO outlined the preliminary audit findings, preliminary conclusions and potential audit recommendations in a report preparation paper (RPP). The RPP was provided to the audited entities for review and feedback. The purpose of the RPP is to inform auditees of issues and assist the ANAO to clarify its audit findings and conclusions. The RPP is also produced to verify the accuracy and completeness of the information the ANAO has gathered and analysed. The RPP is a working paper that is used in the development of a proposed report, which will take into account entity feedback on the RPP and other information. By its nature, the RPP will always include more detail than the final report.

After considering the entity’s response to the RPP and any further information or evidence, the proposed report was drafted, including the Auditor-General’s overall conclusion against the audit objective. The conclusion was given one of four classifications, as outlined below.

Conclusion classifications and 2023–24 regulatory audits

|

Classification |

Number of regulatory audits in 2023–24 |

|

Fully effective |

0 |

|

Largely effective |

2 |

|

Partly effective |

2 |

|

Not effective |

1 |

Source: ANAO analysis of regulatory audit reports.

For the five regulatory audits in 2023–24, the number of recommendations in each report ranged from four to 11 recommendations. Entities were asked to respond whether they agreed or disagreed with the recommendations. Overall, in 2023–24, 94 per cent of Auditor-General recommendations were fully agreed, 5 per cent were agreed with qualification and less than 1 per cent were not agreed.For the regulatory audits, all recommendations, except for one, were fully agreed by the entity, as outlined below.

Number of recommendations for 2023–24 regulatory audits

|

Regulatory audit |

Number of recommendations |

Fully agreed to by the entity (%) |

|

Design and Early Implementation of Residential Aged Care Reforms |

4 |

100 |

|

Management of Non-Compliance with the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 for Unapproved Therapeutic Goods |

6 |

100 |

|

ATO’s Management and Oversight of Fraud Control Arrangements for the Goods and Services Tax |

5 |

100 |

|

6 |

83a |

|

|

11 |

100 |

|

Note a: The entity agreed with five recommendations and ‘partially agreed’ with one recommendation.

Source: ANAO analysis of regulatory audit reports.

After each of the proposed reports were finalised by the Auditor-General, the Auditor-General sent the report to the accountable authority of the audited entity, as required by section 19 of the Auditor-General Act 1997. The accountable authority had 28 calendar days to provide a formal response to the proposed report. In response to formal comments, the Auditor-General may choose to make amendments to the report. The entity’s formal response was included as an appendix in the final audit reports presented for tabling in the Parliament.