Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Biodiversity Fund Program

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of the Environment’s administration of the Biodiversity Fund program.

Summary

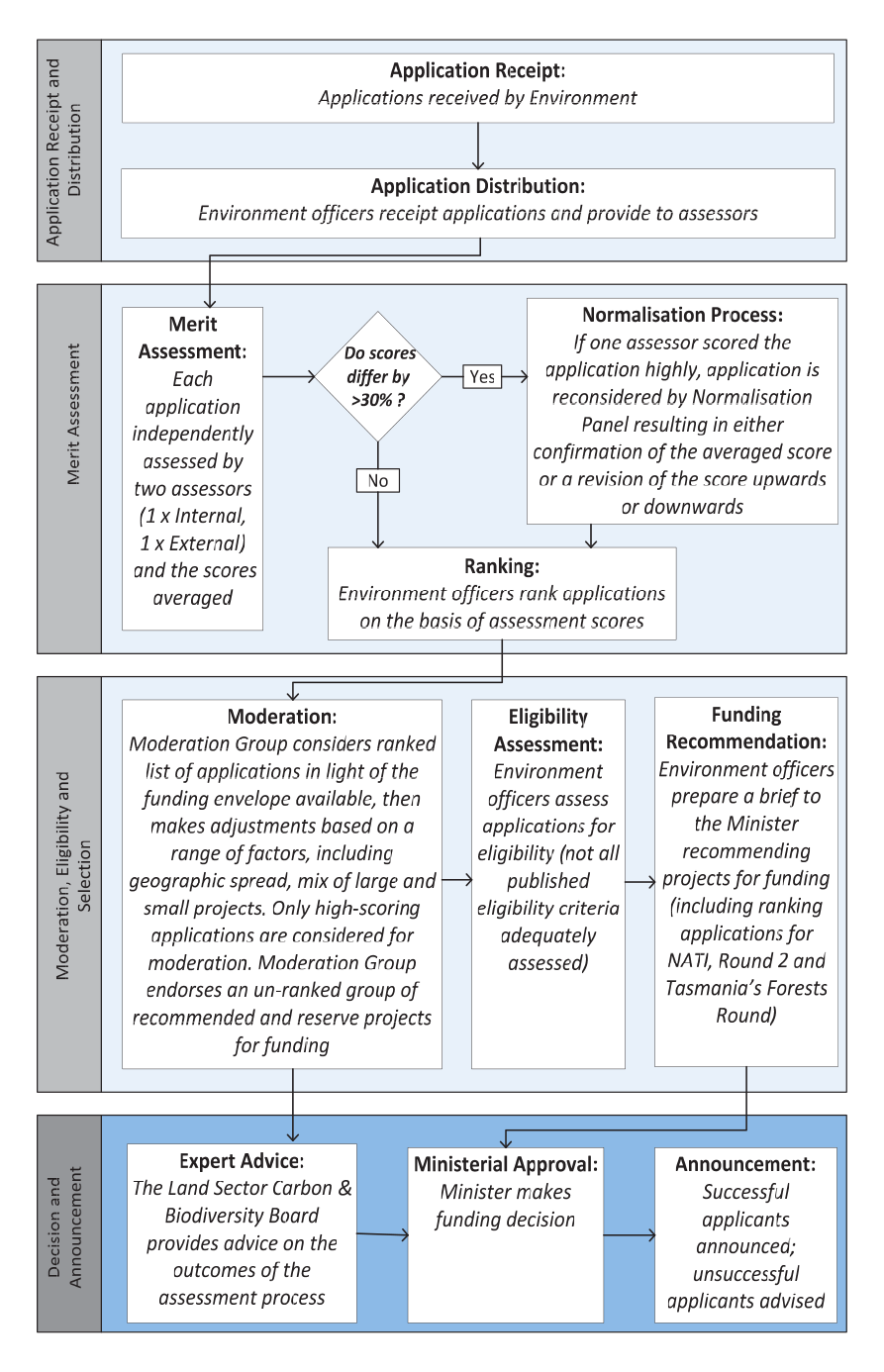

Introduction

Establishment of the Biodiversity Fund program

1. In response to the predicted effects of climate change, successive Australian Governments have committed to a target of reducing Australia’s carbon emissions to a level that is at least five per cent below the year 2000 emission levels, by 2020.1 In July 2011, the then Australian Government announced the Clean Energy Future (CEF) initiative, which outlined planned measures to reduce Australia’s carbon emissions to meet the 2020 target. The four key elements of the CEF initiative were: the introduction of a carbon price; a package of renewable energy programs; a package of energy efficiency programs; and the Land Sector Package, which included the Biodiversity Fund program.

2. The Biodiversity Fund program was established as a competitive, merit-based grants program, with an initial budget of $946.2 million over six years from 2011–12 to 2016–17. The 2013–14 Federal Budget subsequently reduced the overall level of funding by $32.3 million and rephased a further $225.4 million to 2017–18 and 2018–19. The program was closed to new applicants in December 2013. At that time, there was around $324 million in committed expenditure on projects funded under completed funding rounds.2

3. The objective of the Biodiversity Fund program was to: maintain ecosystem function and increase ecosystem resilience to climate change; and increase and improve the management of biodiverse carbon stores across the country. This objective was to be achieved through grants to land managers for on-ground works, such as revegetation, protection of existing biodiversity, and prevention of the spread of invasive species.

Funding rounds and funded projects

4. There were four separate funding rounds completed for the Biodiversity Fund program, prior to the announcement in December 2013 that there would be no further funding rounds. The first round was designed as a ‘development round’ to test program parameters, with subsequent rounds targeting areas requiring further investment. Table S.1 provides an overview of the four funding rounds.

Table S.1: Biodiversity Fund program grant funding rounds

|

Round Name and Applications Period |

Number of Applications Received |

Number of Successful Applications(1) (with funding agreements in place) |

Date Funding Announced and $ Amount |

|

Round 1 9 December 2011 to 31 January 2012 |

1530 Full Applications |

313 |

4 May 2012 $271 million |

|

Northern Australia Targeted Investment (NATI) 5 November 2012 to 4 December 2012 |

183 Expressions of Interest (EOIs) and 55 Full Applications |

3 |

21 August 2013 $9.9 million |

|

Round 2 11 February 2013 to 17 April 2013 |

147 EOIs and 347 Full Applications |

18 |

21 August 2013 $43.4 million |

|

Investing in Tasmania’s Native Forests 20 May 2013 to 12 June 2013 |

29 Full Applications |

0 |

Not announced |

|

TOTAL |

2291 EOIs and Full Applications |

334 funded projects |

$324.3 million |

Source: ANAO analysis of Environment information.

Note 1: Following the Federal Election on 7 September 2013, there were a number of proposed projects that had been approved for funding under the NATI, Round 2 and Investing in Tasmania’s Native Forests rounds, but did not have funding agreements in place at the time that the new Government was sworn in. Funding for these projects did not ultimately proceed.

5. The Department of the Environment (Environment) published program grant guidelines and implemented a broadly consistent application and assessment process across all four funding rounds3, with applications independently assessed against the published merit criteria by both an internal departmental officer and an external community assessor.4 Those applications that were highly ranked at the merit assessment stage were subsequently subjected to a moderation process5, which was designed to, among other things, ensure that there was an appropriate: geographic distribution of projects; balance of funding across program themes and project types; and mix of large and small scale projects. Applications that were recommended for funding following the moderation process were then assessed for eligibility.6

6. Once eligibility was determined, recommended applications were provided to the Minister (the Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities and, subsequently, the Minister for Environment, Heritage and Water) for approval.

7. There were over 2200 applications lodged for the four completed funding rounds.7 Of these, 334 projects were approved and had funding agreements established for a total commitment of around $324 million over six years from 2011–12 to 2016–17.8 Grant recipients are located in every state and territory and include: state government agencies; catchment management authorities; local councils; Landcare groups and other environmental interest groups; Indigenous land management groups; co-operatives of public and private landowners; and individual landowners. The period of funding for approved projects is between two and six years, with funding ranging from just over $7000 to $5.7 million.

Discretionary grants

8. In addition to the grants selected through the competitive merit-based assessment process, there were an additional four discretionary grants awarded under the Biodiversity Fund program, with a total value of $7.65 million (ranging from $176 000 to $6 million).9 The projects funded through these discretionary grants involved: the provision of vegetation planting guides and workshops in 2012; research services in support of monitoring and evaluation activities; the restoration of native forest in Tasmania; and identifying and documenting new plant and animal species.

Administrative arrangements

9. The Biodiversity Fund program is administered by Environment.10 This role has included design of the program, implementation of the grant assessment and selection process for each funding round, and ongoing management of the funded projects. As at 30 June 2014, the division within the department with responsibility for administering Biodiversity Fund program projects (and a range of other Environment programs) had approximately 160 staff.

Audit objective and criteria

10. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of the Environment’s administration of the Biodiversity Fund program. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- governance arrangements were appropriate;

- grant assessment processes to select funded projects under the program were open, transparent, accountable and equitable;

- negotiation and management of funding agreements with approved applicants was sound; and

- effective monitoring, reporting and evaluation arrangements were established to determine the extent to which the program has achieved its objectives.

Overall conclusion

11. The Biodiversity Fund program, administered by the Department of the Environment (Environment), was established as a $946.2 million competitive, merit-based grants program11 as part of the Clean Energy Future initiative.12 The program was designed to protect and enhance biodiversity by providing land managers with grants to undertake on-ground works to revegetate land, protect existing biodiversity, and prevent the spread of invasive species. The program is broad in scope, with funding recipients including individual landholders through to large state government departments, and grants ranging from just over $7000 to almost $6 million.

12. In the main, Environment established suitable arrangements for the administration of the Biodiversity Fund program, including: a governance framework that provided appropriate visibility of program delivery to departmental management; generally sound processes and procedures to underpin the complex grant assessment process; and funding agreements and management arrangements with grant recipients that, in general, supported the delivery of funded projects while protecting the Commonwealth’s interests. There were, however, shortcomings in aspects of the department’s administration of the program, specifically:

- the assessment of each of the eligibility criteria, as outlined in the program’s grant guidelines, was not sufficiently robust or transparent. In particular, there was a lack of clarity in the guidelines relating to some eligibility criteria, limited guidance for departmental assessors undertaking the eligibility assessments, and insufficient documentation to demonstrate that an eligibility assessment had been undertaken against all eligibility criteria for each recommended application; and

- the compliance strategy, which was developed relatively early during program implementation, was not fully implemented. While the department adopted a case management approach, the absence of a risk-based compliance monitoring program, as envisaged in the compliance strategy, reduced the assurance that the department had regarding recipients’ compliance with the obligations established under their funding agreements.

13. In addition to these shortcomings, the availability of discretionary grant funding as an element of the program alongside the delivery of competitive, merit-based funding rounds increased the risks to the equitable treatment of applicants, as not all applicants for program funding were assessed using common criteria. This underlines the importance of applicants’ perspectives being taken into account in the design of grants programs, along with the requirements of government, so that program grant guidelines appropriately inform potential applicants of all program elements to avoid misunderstandings in the way the grants process is to be administered.

14. To strengthen Environment’s administration of grants programs, including the ongoing administration of Biodiversity Fund program projects, the ANAO has made two recommendations in relation to the department: strengthening eligibility assessment processes; and implementing risk-based compliance strategies for grants programs.

Key findings by chapter

Governance arrangements (Chapter 2)

15. The oversight arrangements established within Environment for the Biodiversity Fund program provided a sound basis to guide the delivery of the program.13 Environment produced a range of planning documents that were intended to underpin the implementation of the overarching Land Sector Package (of which the Biodiversity Fund program was a key element) and the delivery of individual funding rounds under the Biodiversity Fund program. The development and regular review of a program-level implementation plan would have better positioned the department to address longer-term delivery issues, some of which became evident during the administration of the program, including the impact of the timing of funding rounds, effective implementation of a compliance strategy, and administrative workloads resulting from the grant recipient reporting schedule.

16. Environment prepared a high-level risk assessment for the Biodiversity Fund program, and also prepared assessments specifically focusing on the four funding rounds conducted for the program. In general, these funding round risk assessments focused on higher-level program implementation risks, and not risks specifically related to each round.14

17. The department established key performance indicators (KPIs) for the Biodiversity Fund program that have been included in its Portfolio Budget Statements, and subsequently performance against these indicators was reported in its annual reports. In the earlier years of program implementation (2011–12 to 2013–14), reported information was generally focused on business processes, such as the management of funding rounds. While the more recent inclusion of outcome-focused KPIs will better place the department to report on the extent to which Biodiversity Fund program objectives are being achieved, Environment is at an early stage in the collection of appropriate information to support reporting against these KPIs.

18. The importance of developing a suitable framework that provides meaningful information about the achievement of natural resource programs’ objectives has been a consistent theme in the ANAO’s audits for over a decade. Environment’s adoption of a performance monitoring and reporting framework that seeks to facilitate the gathering of project-level data that can be used to inform reporting on program-level achievements15, if implemented as intended, has the potential to provide a sound basis for the department to address an area that has been a gap in the administration of programs. However, at the time of the audit, project-level reporting is in its early stages and the planned on-ground scientific monitoring of a selection of project sites and broad-scale monitoring using satellite imagery and other technologies, which would verify and complement the project-level data being collected by funding recipients, is yet to be implemented.

Access to the Biodiversity Fund program (Chapter 3)

19. Environment consulted with stakeholders during the design of the Biodiversity Fund program’s Round 1 and Northern Australia Targeted Investment (NATI) funding rounds, and conducted surveys of funding applicants after the rounds were completed. The department subsequently used appropriate channels to inform potential applicants about the opportunity to apply for funding, including newspaper advertisements, a dedicated website, email newsletters, and use of existing networks with relevant stakeholders.

20. The grant guidelines for the four rounds of the Biodiversity Fund program appropriately outlined the scope, objectives and intended outcomes of the program. The quality of the guidelines for the three later rounds improved when compared to the Round 1 guidelines, and were more clearly expressed and logically structured. There were, however, areas for improvement across all four sets of guidelines, particularly in relation to the role of the Moderation Group and the potential impact of the moderation process on the competitive, merit-based assessment process, the clarity of eligibility criteria, the discretionary grants available under the program, and information regarding available funding in each round and Environment’s preferred budget profile for funded projects.

21. Environment established generally appropriate arrangements to support the grant assessment and selection process, having developed grant assessment plans for each round that outlined key internal procedures. There was, however, a need for clearer guidance for departmental staff undertaking and documenting the eligibility assessments. As was the case with the program’s grant guidelines, there was a general improvement in the quality of the grant assessment plans for the three later rounds when compared to Round 1, indicating that Environment had incorporated the lessons learned over the life of the program. In addition, the probity arrangements established and implemented for the Biodiversity Fund program’s competitive funding rounds were generally proportionate to the risks of the program, and provided the department with assurance that probity and conflict of interest matters had been adequately managed.

Grant assessment and selection (Chapter 4)

22. The grant assessment and selection process was broadly consistent across all four funding rounds. Environment established suitable arrangements for receiving applications and providing confirmation to applicants, primarily through an online application system. While difficulties were experienced with the online lodgement system for Round 1 applications, Environment managed these issues appropriately.

23. The merit assessments prepared by departmental and external assessors were undertaken broadly in accordance with the published guidelines and internal grant assessment plan, although for Round 1, in around one-third of the assessments reviewed by the ANAO the assessors had not provided written comments in support of the scores awarded. The ‘normalisation’ process for applications where the assessor scores varied by more than 30 per cent was also appropriately undertaken and documented, although the basis for decisions to amend merit scores could have been better communicated to the decision-maker.

24. The role of the Moderation Group was to review the merit-assessed applications and recommend projects considered suitable for funding, including ensuring: appropriate geographic distribution of projects across Australia; a balance of funding across program themes and project types; large and small scale projects; and appropriate representation of Indigenous groups. The moderation process was undertaken to help ensure the achievement of the Biodiversity Fund program’s overall objectives. While recognising the appropriate steps taken by the department to administer the moderation process, including probity oversight, the provision of additional information on the process in the grant guidelines for all funding rounds would have contributed to a more transparent assessment and selection process for applicants.

25. The transparency of the decision-making process in each funding round would have been enhanced had the Moderation Group ranked recommended applications in order of merit, rather than grouping them into ‘recommended’ and ‘reserve’ projects.16 In addition, the department did not retain sufficient documentation to clearly explain the basis for its selection of 18 projects from the Round 1 ‘reserve’ list to be recommended for funding, in preference to other more highly-ranked ‘reserve’ projects.

26. Applications that were recommended for funding at the conclusion of the moderation process were then assessed for eligibility. As ‘threshold’ criteria, it is particularly important that eligibility criteria are clearly expressed in the grant guidelines, for agencies to have planned how eligibility assessments are to be undertaken, and for each assessment to be well documented. In this regard, Environment’s assessment of all the eligibility criteria as outlined in the Biodiversity Fund program’s grant guidelines was not sufficiently robust or transparent. In particular, the assessment of whether a proposed project could be considered a ‘business as usual’ activity (and therefore not eligible for funding) was not underpinned by: a clear definition in the published guidelines for Round 117; guidance for departmental staff on conducting this assessment; or sufficient documentation of the assessment of this eligibility criterion for each recommended application. In around one-third of the successful applications reviewed by the ANAO18, at least one assessor had indicated that they considered the proposed project may represent a ‘business as usual’ activity, but the evidence retained by Environment did not indicate that the department followed-up this assessment and, ultimately, no applications were assessed as ineligible against this criterion.

27. Once the merit and eligibility assessment processes were complete, Environment prepared generally appropriate information to support the Minister’s (the decision-maker’s) approval of grant funding. In relation to Round 1, the Minister was not, however, advised that the recommended list of applications included a number of projects that had initially been identified by the Moderation Group as ‘reserve’, or that these applications were not the most highly-ranked on the ‘reserve’ list. The department also notified the successful and unsuccessful applicants of the outcome in each round (although in some rounds, this advice could have been more timely). Relevant information was subsequently published on the department’s website regarding funded projects, as required. The quality of feedback provided to unsuccessful applicants improved in the later three rounds, with information provided in relation to areas for improvement against each merit criterion. There was no evidence to indicate that the location of projects by electorate was a consideration in the distribution of funding.

Selection of discretionary grants (Chapter 5)

28. There were four discretionary grants awarded under the Biodiversity Fund program in addition to the four competitive merit-based funding rounds. While the grant guidelines for Biodiversity Fund program Round 1 had foreshadowed the possibility of discretionary grants where a competitive approach would not be effective or feasible in delivering the desired outcomes of the program, the guidelines for the remaining rounds did not foreshadow this funding option. In the interests of transparency, there would have been merit in the department including a reference to the possibility of discretionary grants in each round’s guidelines and the basis on which applications would be assessed.

29. While all four of the grants had been appropriately approved for funding by the Minister and had funding agreements in place, one grant was awarded at a time when a competitive funding round—that was seeking applications for projects similar to that funded through the discretionary grant—was open. The issues raised by stakeholders with the ANAO in relation to the transparency and equity of this matter illustrate the advantages of implementing merit-based assessment and selection processes for grant programs.

30. In the case of a second discretionary grant, the grant recipient (the Director of National Parks) was involved in recommending the project to the Minister for funding, and Environment has dual ongoing responsibilities involving the delivery of the project19 as well as being the provider of the funding. Notwithstanding the potential environmental benefits of the project, this situation is unusual and presented a number of risks for Environment—particularly in relation to actual or perceived conflicts of interest—which could have been better managed.

Establishment and management of funding agreements (Chapter 6)

31. The established funding agreements for the Biodiversity Fund program appropriately set out the Australian Government’s and grant recipient’s obligations. The adoption of proportional compliance obligations based on risk assessments would have, however, provided the means to balance requirements for an appropriate level of assurance with the potential compliance burden on grant recipients.

32. The funding agreement negotiation and execution period for the Round 2, NATI and Investing in Tasmania’s Native Forests funding rounds coincided with the 2013 Federal Election ‘caretaker’ period. While funding agreements for the NATI and Round 2 approved applicants were provided to applicants shortly after their approval by the Minister, which meant those applicants were afforded the opportunity to execute agreements, approved applicants in the Investing in Tasmania’s Native Forests round were not afforded the same opportunity.20 The records retained by Environment do not clearly demonstrate the basis for this differential treatment.

33. For a significant proportion of Round 1 grant recipients, the department’s re-profiling of their project budget in funding agreements21, and the signing of agreements late in the 2011–12 financial year (which effectively shortened their project by one year) created additional challenges in delivering the project as had been originally planned and set out in their approved application. Improved communication with grant recipients regarding these issues—both in the application and funding execution phases—would have assisted recipients in planning the delivery of their proposed projects.

34. The funding agreements set out a schedule of milestone payments that are based on Environment’s acceptance of six-monthly progress reports by grant recipients. In general, Environment has adequately documented its review of these reports and only released payments following acceptance of the reports. The submission of a large number of reports twice a year has, however, created challenges for departmental staff in reviewing and accepting these reports prior to approving milestone payments (taking an average of six to seven weeks for approval of milestone payments). The resulting delays have reportedly impacted on the cash-flow of some grant recipients.

35. In December 2013, Environment replaced the existing reporting framework with a new online reporting tool—MERIT. MERIT is a key element of the Biodiversity Fund program’s performance monitoring and reporting framework as it seeks to collate comparable data across all projects, to then be correlated and analysed to provide information on the achievement of the Biodiversity Fund program objectives. The transition to MERIT was problematic for some users, and more thorough planning and stakeholder engagement early in the process would have better positioned Environment to assist users to manage this transition.

36. Environment primarily relied on a case management approach (in particular, the review of grant recipient reports) to facilitate compliance monitoring. While Environment had developed a compliance strategy relatively early in the program, it is yet to establish a risk-based compliance monitoring program to provide appropriate assurance in relation to high risk grant recipients’/projects’ compliance with their obligations. There is scope for Environment to more effectively target its compliance strategy for the remaining life of Biodiversity Fund program projects, and to ensure that a risk-based approach to compliance is implemented in future grants programs.

Summary of entity response

37. Environment’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, while the full response is provided at Appendix 1.

The Department is grateful for the opportunity to respond to the audit report and agrees with the two recommendations in the report. The Department notes that the audit has highlighted some areas for future improvement in the grants administration process, particularly in the articulation and assessment of eligibility requirements and in the full implementation of a risk-based compliance strategy to support grants management. The Department has updated its internal processes to improve these areas further and thereby give effect to the audit recommendations, both for the ongoing management of the Biodiversity Fund and for other grants programmes.

The Department also acknowledges the positive findings in the report in relation to the design and implementation of the programme.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 4.34 |

To strengthen the assessment of applicant eligibility under its grants programs, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Environment:

Environment response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 6.63 |

To strengthen the monitoring of compliance with the terms and conditions of funding, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Environment implements risk-based compliance strategies for its grant programs. Environment response: Agreed. |

1. Background and Context

This chapter provides background information on the Biodiversity Fund program and the Department of the Environment’s arrangements for administering the program. It also sets out the audit’s approach.

Introduction

1.1 Over recent years, successive Australian governments have committed to reducing the nation’s carbon emissions to a level that is at least five per cent below the year 2000 emission levels, by 2020.22 In July 2011, the then Australian Government announced the Clean Energy Future (CEF) initiative to support households, businesses and communities to transition to a clean energy future. The four elements of the initiative were: the introduction of a carbon price; a package of renewable energy programs; a package of energy efficiency programs, and the Land Sector Package.23

1.2 The $1.7 billion Land Sector Package (LSP) sought to recognise the important role that farmers and land managers have in reducing carbon pollution and increasing the amount of carbon stored on the land, while maintaining its quality and productive capacity. At the time of its announcement in July 2011, the LSP consisted of the following seven initiatives:

- Biodiversity Fund program ($946.2 million);

- Carbon Farming Futures ($429 million);

- Carbon Farming Initiative Non-Kyoto Carbon Fund ($250 million);

- Regional Natural Resource Management (NRM) Planning for Climate Change Fund ($44 million);

- Indigenous Carbon Farming Fund ($22 million);

- Land Sector Carbon and Biodiversity Board (LSCBB) ($4.4 million); and

- Carbon Farming Skills ($4 million).

1.3 The Department of the Environment (Environment)24 was responsible for implementing four elements of the LSP: the Biodiversity Fund program; the Regional NRM Planning for Climate Change Fund; the Indigenous Carbon Farming Fund; and the LSCBB. The other elements of the LSP were to be implemented by the then Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry or the then Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency.25

Biodiversity Fund program

1.4 The Biodiversity Fund program was established as a competitive, merit-based grants program, with grants provided to assist land managers to: store carbon; enhance biodiversity; and build greater environmental resilience by supporting the establishment of native vegetation; or contribute to the improved management of existing native vegetation.26

Program funding

1.5 The then Government initially allocated $946.2 million to the Biodiversity Fund program over six years from 2011–12 to 2016–17. The 2013–14 Federal Budget subsequently reduced overall program funding by $32.3 million and rephased a further $225 million to 2017–18 and 2018–19. The program was closed to new applicants in December 2013, with around $324 million in committed expenditure on projects funded under completed funding rounds.27

Funding rounds

1.6 Four separate funding rounds were completed for the Biodiversity Fund program (see Table 1.1). The first round was designed as a ‘development round’ to test the program parameters, with subsequent rounds targeting areas requiring further investment. Round 1 was broad in scope, with the majority of the reduced program funding expended in this round (approximately $271 million was approved, compared with a total of $53 million for the three subsequent rounds).

Table 1.1: Biodiversity Fund program grant funding rounds

|

Round Name and Applications Period |

Number of Applications Received |

Number of Successful Applications(1) (with funding agreements in place) |

Date Funding Announced and $ Amount |

|

Round 1 9 December 2011 to 31 January 2012 |

1530 Full Applications |

313 |

4 May 2012 $271 million |

|

Northern Australia Targeted Investment (NATI) 5 November 2012 to 4 December 2012 |

183 Expressions of Interest (EOIs) and 55 Full Applications |

3 |

21 August 2013 $9.9 million |

|

Round 2 11 February 2013 to 17 April 2013 |

147 EOIs and 347 Full Applications |

18 |

21 August 2013 $43.4 million |

|

Investing in Tasmania’s Native Forests 20 May 2013 to 12 June 2013 |

29 Full Applications |

0 |

Not announced |

|

TOTAL |

2291 EOIs and Full Applications |

334 funded projects |

$324.3 million |

Source: ANAO analysis of Environment information.

Note 1: Following the Federal Election on 7 September 2013, there were a number of proposed projects that had been approved for funding under the NATI, Round 2 and Investing in Tasmania’s Native Forests rounds, but did not have funding agreements in place at the time that the new Government was sworn in. Funding for these projects did not ultimately proceed.

1.7 Environment published program grant guidelines and implemented a broadly consistent application and assessment process across all four funding rounds28, with applications independently assessed against the published merit criteria by both an internal departmental officer and an external community assessor.29 Those applications that were highly ranked at the merit assessment stage were subsequently subjected to a moderation process30, which was designed to, among other things, ensure that there was an appropriate: geographic distribution of projects; balance of funding across program themes and project types; and mix of large and small scale projects. Applications that were recommended for funding following the moderation process were then assessed for eligibility.31 Once eligibility was determined, recommended applications were provided to the Minister (the Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities and, subsequently, the Minister for Environment, Heritage and Water)32 for approval.

1.8 Environment received over 2200 Expressions of Interest (EOIs) and full applications over the four completed funding rounds. Of these, 334 projects received funding at a total cost of around $324 million over six years from 2011–12 to 2016–17. Awarded funding was broad in range, varying from $7103 to $5.72 million—of the 334 awarded grants, 73 (22 per cent) received $100 000 or less, while 57 (17 per cent) received over $2 million. Grant recipients included: state government agencies; catchment management authorities; local councils; Landcare groups and other environmental interest groups; Indigenous land management groups; co-operatives of public and private landowners; and individual landowners. Projects are being undertaken in all states and territories, involving activities such as revegetation and pest control (plants and animals), erosion protection and establishment of wildlife corridors. Figure 1.1 shows an example of a Biodiversity Fund program project site visited by the ANAO as part of audit fieldwork.

Figure 1.1: Example of a Biodiversity Fund program project site

Source: ANAO site visits. Invasive willows cleared from a creek bed, to be followed by revegetation with local native plantings.

Discretionary grants

1.9 In addition to the grants selected through the competitive, merit-based assessment process, there were an additional four discretionary grants awarded under the Biodiversity Fund program, with a total value of $7.65 million (ranging from $176 000 to $6 million). The projects funded through these discretionary grants involved: the provision of vegetation planting guides and workshops in 2012; research services in support of monitoring and evaluation activities; the restoration of native forest in Tasmania; and identifying and documenting new plant and animal species.

Administrative arrangements

1.10 The Biodiversity Fund program is managed by the Biodiversity Conservation Division (BCD) within Environment. BCD is responsible for the delivery of a number of environmental programs33, with the divisional structure aligned to operational activities, such as policy development, program planning, grant assessment and selection exercises, and program implementation rather than individual programs. As at 30 June 2014, BCD had around 160 staff, mostly based in Canberra.34

Audit objective, criteria, scope and methodology

1.11 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of the Environment’s administration of the Biodiversity Fund program.

1.12 To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- governance arrangements were appropriate;

- grant assessment processes to select funded projects under the program were open, transparent, accountable and equitable;

- negotiation and management of funding agreements with approved applicants was sound; and

- effective monitoring, reporting and evaluation arrangements were established to determine the extent to which the program has achieved its objectives.

1.13 The ANAO examined Environment’s assessment of grant applications and the funding agreements for approved projects under the Biodiversity Fund program. The audit did not examine other aspects of the LSP or related programs.

1.14 In undertaking the audit, the ANAO:

- reviewed departmental files and program documentation;

- interviewed and/or received written input from departmental staff and relevant stakeholders, including grant recipients, chairs of the assessment Moderation Groups, and peak environment groups;

- conducted a survey of a sample of grant recipients to canvas their views on the department’s administration of the program;

- undertook site visits to 10 Biodiversity Fund program projects located in regional New South Wales and Victoria; and

- examined a random sample (20 per cent) of unsuccessful and successful grant applications, including the funding agreements of successful applicants.35

1.15 The analysis of grant applications was undertaken to provide additional assurance that: applicants provided the required information; the assessment and selection process was undertaken in accordance with the grant guidelines and was transparent and accountable; and that for funded projects, agreed milestone requirements had been met before payments were released.36

1.16 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $641 000.

Report structure

1.17 The structure of the report is outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Structure of the report

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

2. Governance Arrangements |

Examines the governance and oversight arrangements established and implemented by Environment for the Biodiversity Fund program, as well as the development of a performance monitoring and reporting framework. |

|

3. Access to the Biodiversity Fund Program |

Examines access to the Biodiversity Fund program, including stakeholder engagement, development of the program’s grant guidelines, and preparation for the grant assessment and selection process. |

|

4. Grant Assessment and Selection |

Examines the grant assessment and selection processes implemented by Environment for the four Biodiversity Fund program funding rounds. |

|

5. Selection of Discretionary Grants |

Examines the four discretionary grants that were funded under the Biodiversity Fund program. |

|

6. Establishment and Management of Funding Agreements |

Examines Environment’s development and ongoing management of Biodiversity Fund program funding agreements. |

2. Governance Arrangements

This chapter examines the governance and oversight arrangements established and implemented by Environment for the Biodiversity Fund program, as well as the development of a performance monitoring and reporting framework.

Introduction

2.1 The administration of programs requires effective governance arrangements to guide and support program delivery. The ANAO examined the governance arrangements implemented by Environment for the Biodiversity Fund program, including oversight arrangements, planning for the program, the assessment of risk and the establishment of a performance monitoring and reporting framework.37

Administration and oversight arrangements

2.2 The oversight arrangements established within Environment for the delivery of the Biodiversity Fund program were:

- a Project Board chaired by one of Environment’s Deputy Secretaries, with representation from senior departmental executives. The Project Board’s role was to provide high-level guidance on the planning, implementation and reporting requirements for the four Land Sector Package measures;

- a Project Sponsor (First Assistant Secretary level member of the Project Board who had overall responsibility for the delivery of the Biodiversity Fund program); and

- a Project Manager (Assistant Secretary with day-to-day responsibility for delivering Biodiversity Fund program activities).

2.3 Following the announcement of the CEF initiative in July 2011, Environment established a taskforce38 to commence planning and implementation of Environment’s responsibilities under the Land Sector Package, including the Biodiversity Fund program. The taskforce prepared regular performance reports for the Project Board.

2.4 Subsequently, the taskforce was integrated into the Biodiversity Conservation Division (BCD) in July 2012. The ANAO was informed by the department that the management of funded projects under the Biodiversity Fund program is now considered a ‘business as usual’ activity and, as such, performance reports are only prepared for the Project Board on an exceptions basis, where issues arise. Overall, the departmental oversight arrangements established for the Biodiversity Fund program provide an appropriate level of oversight.

Land Sector Carbon and Biodiversity Board

2.5 The LSCBB was established under the Climate Change Authority Act 2011, as part of the CEF initiative. In relation to the Biodiversity Fund program, the specific role of the LSCBB was to:

- advise on the development of key performance indicators;

- advise on the implementation of the guidelines;

- consider the assessment process undertaken in relation to the grants program;

- review the grant assessment and selection report for each funding round; and

- provide advice concerning project recommendations made by the Moderation Group to the Minister.

2.6 Environment provided advice and information to the LSCBB in support of its role in Biodiversity Fund program delivery, and the LSCBB discharged its functions in relation to the program. As required under the Climate Change Authority Act 2011, the LSCBB produced an annual report in 2011–12 outlining the measures initiated under the LSP, including the Biodiversity Fund program.39

Program planning

2.7 As the responsible administering agency, it was Environment’s responsibility to design the approach for the delivery of the Biodiversity Fund program.40 As previously outlined in Chapter 1, the program’s high-level objectives had initially been designed and announced as part of the wider LSP.

Project plans

2.8 The department adopted a staggered approach to program planning. In October 2011, Environment developed an overarching Governance and Reporting Project Plan for the delivery of the LSP, with separate project plans subsequently developed for the Biodiversity Fund program and the other three LSP programs being implemented by the department.

2.9 Environment developed two Biodiversity Fund program project plans over the life of the program. These plans covered Round 1 and the Northern Australian Targeted Investment (NATI) round. The plans included: the program scope; governance arrangements; work plans (to track progress against implementation); communication plans; quality management processes; reporting schedules and escalation triggers. The department also developed risk assessment and treatment plans as attachments to the project plans (discussed later in this chapter).

2.10 Environment informed the ANAO that project plans were not developed for Round 2 and the Investing in Tasmania’s Native Forests round, because these rounds were considered ‘business as usual’ activities, with the planning previously undertaken (particularly for NATI as a targeted investment round) deemed to be sufficient. However, each of the four funding rounds had differing timeframes, areas of targeted focus, and selection processes (including an EOI process for NATI and Round 2), resulting in differing stakeholder groups and risks to implementation. In addition, the department undertook a number of restructures throughout the life of the program that changed Biodiversity Fund program resourcing and program oversight arrangements.

2.11 In light of Biodiversity Round 1 being considered a ‘development round’ ahead of more targeted funding rounds, there would have been merit in the department developing an overarching implementation plan to address high-level implementation issues such as: timeframes; roles and responsibilities; resourcing; risk management; and monitoring and reporting. Lower-level, funding-round specific tasks could have been addressed in individual project plans, if considered necessary. Such an approach would have enabled Environment to address issues, such as program overlaps, and adequately plan to mitigate program level risks.

Communication plans

2.12 Environment developed two communication plans during the implementation of the Biodiversity Fund program, in conjunction with the project plans developed for Round 1 and the NATI round outlined earlier. The communications plans outlined: the aim of the plan; key messages to be conveyed; target audiences; timelines for communication activities; sensitivities; and potential stakeholder concerns. Communication plans were not, however, prepared for Round 2 and the Investing in Tasmania’s Native Forests round. The establishment of fit-for-purpose plans for each round would have helped to ensure that stakeholders were appropriately informed of the program parameters specific to each round.41

Risk management

2.13 Environment developed a Land Sector Package Risk Plan in August 2011, which identified three high level LSP risks: ineffective stakeholder consultations; ineffective governance arrangements; and ineffective administrative arrangements. These identified risks were subsequently used to inform the development of the Biodiversity Fund Risk Plan.

Biodiversity Fund Risk Plan

2.14 The Biodiversity Fund Risk Plan42 identified nine risks in relation to planning and implementation, and outlined existing and planned mitigation controls. These risks comprised a ‘mix’ of higher-level, longer term risks to the delivery of the Biodiversity Fund program, and risks related directly to forthcoming grants funding rounds. The plan was updated over time, with additional risks identified and mitigation strategies planned, as the program progressed. The Project Board subsequently considered risks over the course of the Biodiversity Fund program’s implementation.

Funding round risk assessments

2.15 Environment also developed a risk assessment for each funding round (with the risk in each case determined to be ‘low’).43 However, the ANAO noted that, overall, the risk assessments prepared by Environment outlined higher-level program risks, rather than risks related more directly to the implementation of the funding round subject to the assessment.44 The assessment provided to the Minister for Round 1 replicated the Biodiversity Fund Risk Plan (with its nine risks as outlined earlier). The risk plans for the Round 2 and the Investing in Tasmania’s Native Forests round were also identical, despite these rounds targeting substantially different geographical areas and potential applicants.

2.16 To help ensure that risks are sufficiently addressed, risk plans developed for each funding round and mitigation strategies should take into account the risks specific to the effective conduct of each round, accepting that there are likely to be risks that are common to each round. In relation to the Biodiversity Fund program, some risks that commonly occur during the implementation of grants programs were realised, such as problems with the application lodgement system and over-subscription of the program—which led to amendments to the planned assessment process and additional time pressures. Environment would have been better placed to plan for, and address, these risks if the risk plans had more closely reflected the changing and emerging risks specific to each funding round.

Performance measurement and reporting

2.17 The Government’s Outcomes and Programs Framework, which was in place at the time of the establishment of the Biodiversity Fund program and during the audit fieldwork45, requires agencies to report on the extent to which the programs they administer contribute to established outcomes. A central feature of this approach is the development of clearly specified outcomes, program objectives, deliverables and appropriate key performance indicators (KPIs).

Performance monitoring

2.18 Performance information relating to the Biodiversity Fund program was first included in Environment’s Portfolio Additional Estimates Statement 2011–12 under the department’s Outcome 1, and has been included in the subsequent Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS).46 Environment has reported against the Biodiversity Fund program KPIs in its annual reports from 2011–12 to 2013–14.

2.19 In the 2012–13 PBS, Environment acknowledged that the KPIs measured business processes (such as conducting funding rounds), and stated that ongoing (outcome) KPIs were being developed.47 While deliverables and KPIs outlined in the PBS for the subsequent years continued to focus on implementation activities, indicators that would assist stakeholders to determine progress towards achievement of environmental outcomes were also included. For example, the following KPI was included in the 2013–14 PBS:

Establishing, restoring and/or protecting biodiverse carbon stores by:

- supporting revegetation;

- managing and protecting existing biodiverse carbon stores in high conservation value areas; and

- supporting actions that prevent the spread of invasive species across connected landscapes.48

2.20 The department’s 2013–14 Annual Report subsequently reported against this KPI, stating that under the Biodiversity Fund program 22 major projects were supported to achieve these objectives.49

2.21 The most recent PBS (2014–15) also included an additional Biodiversity Fund program KPI:

An increase in condition and extent of native vegetation in project areas, (from baseline reported in July 2014) to July 2015.50

2.22 In November 2014, the department informed the ANAO that progress against this indicator would not be reported until the 2015–16 Annual Report, as the varying timeframes for grant recipients to supply monitoring data meant that a full data set to underpin the reporting would not be available for the 2014–15 Annual Report.

2.23 Environment’s establishment of the MERI Framework to collect project data to inform ongoing monitoring and reporting of the Biodiversity Fund program’s overall performance is discussed in the following section.

Monitoring, Evaluation, Reporting and Improvement (MERI) Framework

2.24 Over several decades, successive Australian Governments have implemented large-scale natural resource management programs that have, cumulatively, involved the expenditure of billions in taxpayer dollars. Historically, there has been a lack of information about the overall (program-level) achievement of the stated objectives for these programs. The need to develop and implement a suitable performance framework that provides meaningful information to assess the success (or otherwise) of natural resource programs has been a matter raised in ANAO audits for over a decade.51

2.25 Since 2009, Environment and the Department of Agriculture have been working to develop and implement an outcomes-based reporting framework—the Monitoring, Evaluation, Reporting and Improvement (MERI) Framework—that can be applied across Australian Government funded natural resource management programs.52 The MERI process is designed to promote continuous involvement, communication and learning rather than viewing evaluation as a single event that occurs at the completion of the program.

2.26 The Biodiversity Fund program is one of several programs administered by Environment that is applying the MERI Framework, underpinned by three complementary monitoring activities:

- grant recipient monitoring (project-level—discussed in Chapter 6);

- targeted on-ground scientific monitoring (program-level); and

- broad landscape-scale monitoring (program-level).

2.27 Environment developed a draft Biodiversity Fund Monitoring and Reporting Framework in November 2012.53 In April 2013, the department released a public strategy document that outlined, at a high-level, the MERI Framework and how it was intended to be implemented as part of the Biodiversity Fund program and the then Caring for Our Country initiative. In mid-2013, Environment finalised a Biodiversity Fund MERI Plan, which included a set of KPIs and key evaluation questions.

2.28 The plan provided an appropriate basis on which to implement the MERI Framework for the Biodiversity Fund program. The inclusion of a number of new KPIs, which could be used to provide useful information in support of improved performance reporting in the PBS and annual report framework (as discussed earlier), will better place the department to measure program achievements. There was also scope for the department to have developed interim or proxy measures that would have been used to measure performance pending the development of new KPIs.

2.29 As outlined earlier, the monitoring activities to be undertaken under the MERI Framework also include targeted on-ground scientific monitoring and broad landscape-scale monitoring. Environment has undertaken a range of activities to prepare for and underpin scientific and landscape-scale monitoring as part of the MERI Framework. However, as at November 2014, the on-ground scientific monitoring program had yet to be implemented due to resourcing constraints, with work to progress the implementation of broadscale monitoring activities at an early stage.

Conclusion

2.30 The arrangements established for the Biodiversity Fund program, including a Project Board that received regular progress reports, provided an appropriate level of oversight of the program. Environment also produced a range of planning and risk assessment documents that were intended to underpin the delivery of the overarching LSP and the individual funding rounds under the Biodiversity Fund program. The development and regular review of a program-level implementation plan would have better positioned the department to address longer-term delivery issues. There was also scope for the department to have better refined its risk identification and mitigation processes to address the risks specific to each funding round.

2.31 The department has established and reported against KPIs for the Biodiversity Fund program, although performance information has generally been focused at the activity level. In recent years, Biodiversity Fund program KPIs have been augmented with additional measures that directly relate to achievement of the program’s objectives and the department’s broader outcomes, with implementation of the MERI Framework providing the basis for reporting on outcome-level achievements into the future. While the ANAO’s review of the implementation of the MERI Framework has been limited to the early stages of the on-ground reporting system, the planned framework, if implemented in its entirety, has the potential to provide a sound basis for the department to report on the outcomes of long-term environmental projects, such as the Biodiversity Fund program.

3. Access to the Biodiversity Fund Program

This chapter examines access to the Biodiversity Fund program, including stakeholder engagement, development of the program’s grant guidelines, and preparation for the grant assessment and selection process.

Introduction

3.1 An early and important consideration in the design of a grants program is establishing the process by which potential grant recipients will be able to access the program.54 The ANAO examined Environment’s approach to ensuring access to the four rounds of the Biodiversity Fund program, including:

- stakeholder engagement;

- development and content of the grant guidelines;

- preparation for the grant assessment and selection process; and

- planning and implementing the management of probity and conflicts of interest.

Stakeholder engagement

3.2 Environment conducted a range of stakeholder engagement activities in developing and implementing the Biodiversity Fund program, including an industry roundtable, consultative meetings, surveys, the dissemination of information in newsletters, and direct correspondence between stakeholders and the department.

Stakeholder consultation prior to funding rounds

3.3 Environment held an industry roundtable before the opening of the application period for Round 1, with participating stakeholders including representatives from the revegetation industry, the carbon management industry, nurseries, research bodies (universities and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation), catchment management authorities, Greening Australia, and botanic gardens.

3.4 The roundtable, which was held on 30 November 2011, introduced stakeholders to the scope and objectives of the Biodiversity Fund program. Environment informed roundtable participants that guidelines for Round 1 would be released before Christmas 2011 and that the funding round would be deliberately broad in scope. The roundtable did not, however, include a consideration of the draft guidelines, as they had already been submitted to the Minister for approval when the roundtable was held.55

3.5 Prior to the launch of the NATI round, the department also held stakeholder meetings in Broome, Darwin and Townsville during July 2012.56 These meetings canvassed opportunities for biodiversity conservation across northern Australia, with participants providing suggestions for improvement to application and project reporting processes.

Informing potential applicants

3.6 Stakeholders were provided with information about the Biodiversity Fund program rounds through a range of mechanisms, including newsletters from natural resource management (NRM) bodies, newspaper advertisements, the department’s website, and Australian Government Regional Landcare Facilitators.57

3.7 Environment’s stakeholder surveys (discussed later) indicated that potential applicants were adequately informed of the opportunity to apply for grants under the Biodiversity Fund program. The ANAO’s consultation58 with stakeholders also indicated that there was strong interest from potential applicants. Further, the large number of applications lodged under each funding round indicated that stakeholders were aware of the program.

3.8 Additional support tools were made available to potential applicants during application periods, including: online frequently asked questions; the department’s Community Information Unit (1800 number); the Biodiversity Fund program website; and direct emails to the Biodiversity Fund program inbox. Feedback to the department from Round 1 participants indicated that this supporting information was, in most cases, useful to potential applicants.

Timing of Round 1 application period

3.9 A key concern raised by applicants that had participated in Round 1 was the timing of the application period (9 December 2011 to 31 January 2012). A number of applicants commented to the ANAO that conducting an application round over the Christmas/New Year period created additional difficulties. For example, some applicants experienced problems in negotiating with project partners due to the absence of personnel and a general lack of resources over the holiday period to complete applications. These concerns were also expressed in responses to Environment’s post-Round 1 survey, with some applicants stating that the timing of the application period caused considerable stress.

Stakeholder consultation after funding rounds—surveys

3.10 Environment conducted a number of stakeholder surveys after the completion of funding rounds to seek feedback from both applicants and grant assessors about the implementation process and policy settings for the Biodiversity Fund program.59 In Round 1, these surveys formed part of Environment’s internal review of implementation. In response to the survey results, Environment improved implementation arrangements for later rounds—for example, in relation to the clarity of grant guidelines and the alignment of application forms and assessor scoring tools.

Grant guidelines

3.11 Agencies are required to develop guidelines for new grant programs and to make them publicly available, to allow eligible persons and/or entities to apply for a grant under the program. The ANAO reviewed the development of the Biodiversity Fund program grant guidelines for each funding round to assess the appropriateness of the information provided to potential applicants.

3.12 The program area with responsibility for developing the guidelines consulted appropriately with key internal stakeholders (including Environment’s legal area60, other government agencies involved in the LSP, the LSCBB and the Minister’s Office) on the content of the guidelines for all four rounds.

3.13 While the department conducted a stakeholder roundtable shortly before the release of the Round 1 guidelines and also held meetings with stakeholders prior the NATI round (as outlined earlier), draft guidelines were not made available to external stakeholders for comment prior to their publication for any of the funding rounds.61 Releasing draft guidelines to potential applicants for feedback, as Environment has done for other recent grants programs62, would have provided greater assurance regarding the clarity and completeness of the guidelines.

Content of the grant guidelines

3.14 The guidelines for each of the four rounds clearly outlined the scope, objectives and intended outcomes of the Biodiversity Fund program, as well as the merit selection criteria for each round. Over the course of the four rounds, the guideline documents generally improved in clarity. When compared to Round 1, the guidelines for the three later rounds were more clearly expressed and logically structured. For example, key information for applicants was given prominence in the guidelines for later rounds (such as information about important dates and a summary of key issues for potential applicants to consider prior to applying), while background and general information received less prominence.

3.15 Stakeholder feedback on the guidelines was positive overall, with more than 97 per cent of ANAO survey respondents stating that they found the grant guidelines ‘reasonably clear’ or ‘very clear’.

3.16 There was, however, scope to improve several aspects of the guidelines. Specifically, the provision of greater clarity and additional guidance in relation to the moderation process, eligibility criteria, discretionary grants, and budget information for each round would have enabled potential applicants to make more informed decisions regarding their participation in the program.

Moderation process

3.17 There was scope for the guidelines, particularly those for Round 1, to have provided greater clarity regarding the role of the Moderation Group and the impact of the moderation process on the outcomes of the assessment and selection process. The Round 1 guidelines did not explicitly outline the role of the Moderation Group, which was an important element in the assessment and selection of applications for funding. The only reference in the Round 1 guidelines to a process that was additional to the initial merit assessment was to ‘consideration [being] given to achieving a reasonable distribution of projects across the country and across themes’.63 The guidelines in the three subsequent rounds were clearer on the involvement of the Moderation Group, for example the NATI Guidelines stated:

The Moderation Group may consider proposals in the context of:

- effective partnerships and collaboration in achieving biodiversity outcomes across Northern Australia;

- the extent to which proposals complement and support projects already funded under the program and/or other proposals submitted in the round;

- the spread of projects across the Northern Australia investment area; and

- the spread of projects across activity type and organisation.64

3.18 The inclusion of information in the grant guidelines on the moderation process for all rounds, including the impact of the process on the outcomes of the assessment and selection process65, would have assisted potential applicants to make informed decisions regarding whether to apply, and the number and type of applications that they would lodge.

Eligibility criteria

3.19 Eligibility or ‘threshold’ criteria are those that must be satisfied in order for an application to be considered for funding. Grant guidelines should clearly identify eligibility criteria so that potential applicants can make an informed decision as to whether to invest resources in developing an application.66 The guidelines for each of the four rounds included a section outlining who was eligible to apply for funding, as well as the project activities that would be considered ineligible. Eligibility requirements varied from round-to-round, although certain key eligibility criteria were required to be met in all four rounds.

3.20 When compared to Round 1, the guidelines for the NATI, Round 2 and Investing in Tasmania’s Native Forests round presented the eligibility criteria more clearly. In these later rounds, the addition of glossaries to define key terms such as ‘business as usual’ and ‘in-kind contributions’ also helped to inform potential applicants about eligibility requirements. Notwithstanding the inclusion of this additional information in later rounds, some eligibility criteria were broad and difficult for applicants to interpret and the department to assess—for example, ‘a project not representing “business as usual” activities’. There was scope for Environment to have more clearly outlined requirements to potential applicants and to assist assessors to more easily determine eligibility. This matter is discussed in further detail in Chapter 4, from paragraphs 4.28 to 4.33.

Discretionary grants

3.21 The grant guidelines for Round 1 of the Biodiversity Fund program had outlined to potential applicants the possibility that discretionary grants would be available ‘where a competitive approach would not be effective or feasible in delivering the desired outcomes of the program’.67 However, the guidelines did not outline the basis upon which applications for a discretionary grant would be assessed and recommended for funding. The guidelines for the subsequent three rounds did not outline the availability of discretionary grants under the program. In the interests of transparency, there would have been merit in including advice to grant applicants on the availability of discretionary grants, and the basis on which they would be made, in the guidelines for all funding rounds. The selection and administration of discretionary grants under the Biodiversity Fund program is discussed further in Chapter 5.

Budget information

3.22 While the initial total funding ($946.2 million) for the Biodiversity Fund program across the years 2011–12 to 2016–17 was outlined in the Round 1 guidelines, only the NATI guidelines clearly stated the total allocated budget ($50 million) for that particular round.68 The guidelines for the other three rounds did not specify the total funding envelope available. Providing information about the total funding available for a granting activity helps to promote transparent and equitable access to grants, enabling potential applicants to better assess whether it is worthwhile applying for funding.69 On this matter, a stakeholder commented to the ANAO that:

The government need[s] to be explicit with the amount of dollars allocated to a funding round. Then applicants can make a choice if it is worth applying for funds if they are outside of a priority area.

3.23 Environment informed the ANAO that, in relation to Round 1, the information was not included in the guidelines because the budgetary environment was uncertain at the time of the release of the guidelines. The department has, however, acknowledged that it is normal practice to include available funding in grant guidelines.

3.24 The grant guidelines and/or other materials also did not provide guidance to applicants about Environment’s preferred funding profile for individual project budgets (for example, if the department had a preference for 10 per cent of the project’s total to be expended in year one, 20 per cent in year two, and so on). This had particular consequences for projects funded through Round 1 (this issue is discussed in Chapter 6).

Preparing for the assessment and selection process

3.25 To prepare for the assessment and selection process, Environment developed grant assessment plans, and recruited assessors and delivered assessor training.

Grant assessment plans

3.26 Environment prepared a grant assessment plan for each round of the Biodiversity Fund program to provide guidance to departmental officers and assessors involved in the assessment process, as required by its internal grants administration guide.70

3.27 Overall, the grant assessment plans provided a useful outline of the assessment process for each round. While the Round 1 grant assessment plan generally contained less detail on certain aspects of the grant assessment process, the plans for the NATI, Round 2 and Investing in Tasmania’s Native Forests rounds included additional information in relation to the procedures for:

- the receipt and handling of applications, including electronic, hardcopy and handwritten applications;

- handling late applications;

- responding to the failure of the online application form;

- allocation of applications to external and internal assessors (and reallocation, if necessary); and

- notification and feedback, including the appeals process.

3.28 The additional detail in these later plans demonstrates that Environment had responded to the lessons learned from Round 1. However, there was scope for improvement in the plans for all rounds in relation to eligibility assessment, with information on eligibility assessment varying across the plans for each of the four rounds. While the plans covered eligibility assessment to some extent, the NATI plan provided additional guidance in relation to the eligibility assessment process. Further, not all eligibility criteria, as described in the guidelines for each round, were listed in the relevant grant assessment plans. Conversely, some eligibility criteria were described in the grant assessment plan that had not been set out in the relevant guidelines document.71 The alignment of the grant guidelines and the assessment plans helps to ensure that the assessment process is conducted in a transparent and accountable manner.72

Assessor recruitment and training

3.29 In accordance with the grant assessment plans for each round, each application was to be assessed by a community (or external) assessor and a departmental (or internal) assessor. Environment recruited community assessors to participate in each of the four rounds, with selection made on the basis of their skills, experience and/or technical knowledge in natural resource management, as well as their local knowledge. These assessors were selected from Environment’s existing panel of community assessors.

3.30 Both internal and external assessors were provided with training prior to the assessment period for each round, which consisted of one day of training in Canberra, an assessor information pack, presentations and opportunities for discussion and questions, as well as mock assessments. Environment’s surveys of its assessors indicated that most assessors considered they had been wellprepared for the assessment task and were well-supported by the department during the assessment phase.

Managing probity and conflicts of interest

3.31 The use of experts can add value to grant assessment and selection processes, particularly where the grants relate to specialised activities such as environmental projects.73 However, such involvement, particularly if there are links between the expert/s and the pool of potential applicants, can present a higher probity risk in relation to the potential for (actual or perceived) conflicts of interest.74 The ANAO examined the department’s probity planning, the role of the probity adviser in the competitive grant assessment and selection processes, and the steps taken by Environment to manage potential and actual conflicts of interest.

Probity planning

3.32 While Environment did not develop a specific probity plan for the Biodiversity Fund program, each round’s grant assessment plan included a section describing probity principles75 that would underpin the administration of the program. Procedures to support these probity principles were included in the grant assessment plans for each round.

3.33 Environment also engaged a legal services firm to provide probity advice on the Biodiversity Fund program, with the role of the probity adviser described in the grant assessment plans for each round.

Probity adviser

3.34 The probity adviser played an active role throughout the four competitive merit-based grant assessment rounds.76 In particular, the adviser:

- provided input to the development of guidelines, application forms, grant assessment plans and assessment criteria and other supporting materials, such as training for assessors;

- provided advice on requests for extensions for submitting applications, and on other matters, such as procedures for distributing applications to assessors;

- provided advice in Round 1 on the design and implementation of the ‘normalisation’ process (which is described in Chapter 4 at paragraph 4.14);

- attended all meetings of the Normalisation Panels and Moderation Groups, and provided advice where requested; and

- prepared a probity report that provided an overview of the processes undertaken for each round and the probity adviser’s certification that these processes were defensible from a probity perspective.

3.35 Given the complex grant assessment and selection process that was implemented for the Biodiversity Fund program, including the involvement of a Moderation Group (discussed further in Chapter 4), having an independent probity adviser in each funding round helped to provide the department with additional assurance regarding the equity, accountability and transparency of the assessment and selection processes.

Management of conflicts of interest

Grant assessors

3.36 Environment sought the involvement of external or ‘community’ assessors in the grant assessment process for each funding round because of their broad community and local knowledge, as well as their technical or scientific understanding of the complex issues involved in natural resource management. A risk in this approach was that assessors may have professional and/or personal relationships with applicants that they are required to assess (particularly as Environment intended to allocate applications to external assessors from their regions to draw on their local experience).

3.37 Environment sought to manage these risks by providing appropriate training and documented guidance to assessors in relation to conflicts of interest. The department also put in place the following procedures, which were outlined in the grant assessment plans for each round:

- a requirement for assessors to make a conflict of interest declaration before commencing the assessment process;

- allocation (and re-allocation if required) of applications among assessors taking into account declared conflicts of interest; and

- a requirement for assessors to declare to the Program Manager any potential conflicts of interest arising during the assessment process as soon as possible.77

3.38 External assessors were also required to complete and sign a privacy and confidentiality deed that provided an undertaking not to access, use, disclose or retain personal or confidential information except as part of their Biodiversity Fund program assessment responsibilities.

3.39 In a sample reviewed by the ANAO, all assessors had in place a conflict of interest declaration prior to the commencement of their assessment work, as well as a signed privacy and confidentiality deed.78 The case study below demonstrates how Environment managed conflict of interest situations for assessors.

Table 3.1: Case study—management of conflict of interest issues during Biodiversity Fund program assessment processes

|

During the assessment phase for Round 1, Environment became aware that a community assessor had also submitted an application for funding on the basis that they had been advised during training that they could do so. The probity adviser informed Environment that it would be unfair to exclude this application from consideration, based on the advice the assessor had received during training. However, the probity adviser also noted that it was not ideal for project participants to have dual roles and proposed a number of strategies to minimise the probity risk for a potentially conflicted assessor (including reallocating applications similar in nature to the one submitted by the assessor). Environment did not identify any other assessors who had also submitted an application for funding. |

Source: ANAO analysis of Environment information.

Moderation Group

3.40 Potential conflicts of interest for members of each Moderation Group were to be managed through written declarations79, as well as by requiring a conflicted group member to leave the room during discussion of relevant applications. These procedures were set out in the grant assessment plans for the NATI, Round 2 and Investing in Tasmania’s Native Forests rounds. Probity reports prepared for each funding round indicate that these planned processes were implemented.

Conclusion