Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Organ and Tissue Donation: Community Awareness, Professional Education and Family Support

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Authority's administration of community awareness, professional education and donor family support activities intended to increase organ an

Summary

Introduction

1. The Australian organ and tissue donation system is based on an ‘informed consent’ (or opt-in) model, whereby individuals agree to donate their organs and tissue in the event of their death.1 Individuals can record their consent or objection to becoming an organ and/or tissue donor on the Australian Organ Donor Register (AODR).2 Regardless of whether an individual has registered their consent for donation, the practice in Australia is to also seek agreement from a donor’s next of kin before donation proceeds.3

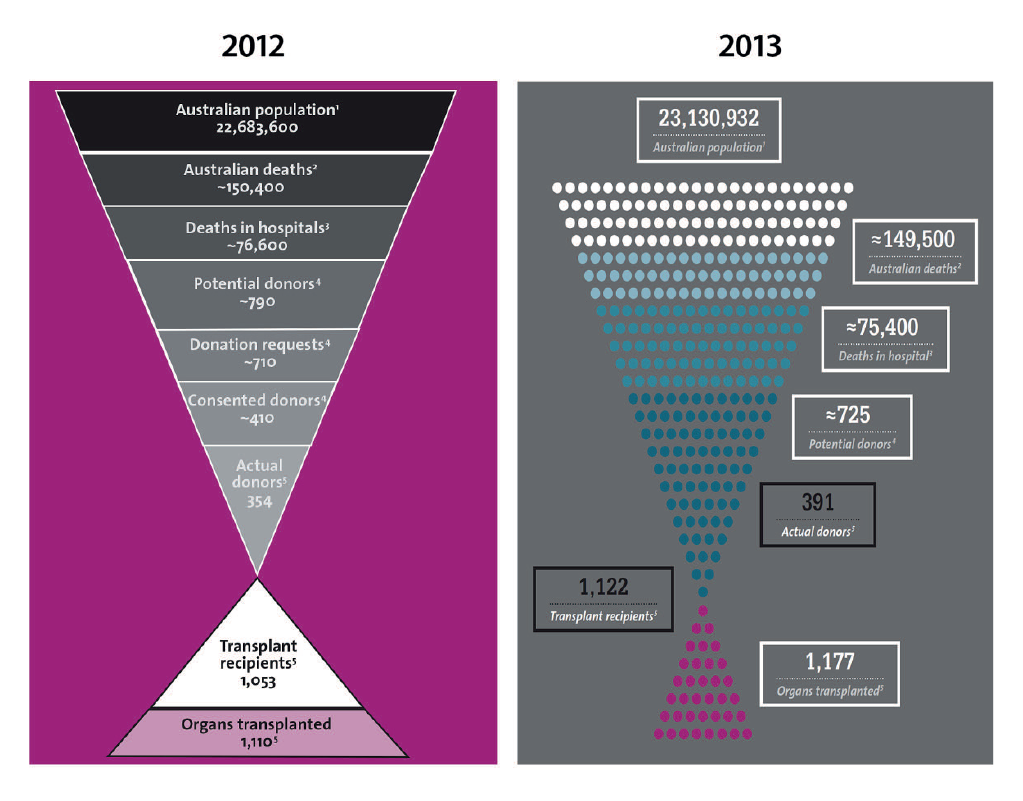

2. Australia’s rate of organ and tissue donation does not meet the current demand for transplantation. In 2014, an average of 1632 people were on organ transplant waiting lists each month, and in total, 1117 people received organ transplants. In the same year, 5553 people received tissue transplants.

3. In October 2006, the then Australian Government established the National Clinical Taskforce on Organ and Tissue Donation (the Taskforce) to provide evidence-based advice on ways to increase the rate of organ and tissue donation.4 In response to the Taskforce report, the Australian Government announced in July 2008 a national reform program to ‘establish Australia as a world leader in organ donation for transplantation’.5 Endorsed by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), the national reform program committed $136.4 million in new Australian Government funding over four years (2008–2012) to improve access to transplants through a nationally coordinated approach to organ and tissue donation.

4. The national reform program had two objectives: to increase the capability and capacity within the health system to maximise donation rates; and raise community awareness and stakeholder engagement across Australia to promote organ and tissue donation. Nine measures were endorsed by COAG aimed at achieving the two broad program objectives:

- Measure 1: A new national approach and system – a national authority6 and network of organ procurement organisations.

- Measure 2: Specialist hospital staff and systems dedicated to organ donation.

- Measure 3: New funding for hospitals.

- Measure 4: National professional awareness and education.

- Measure 5: Coordinated ongoing community awareness and education.

- Measure 6: Support for donor families.

- Measure 7: Safe, equitable and transparent national transplantation process.

- Measure 8: National eye and tissue donation and transplantation.

- Measure 9: Additional national initiatives, including living donation programs.

5. This audit focussed on Measures 4 to 6 highlighted above, relating to: professional education; community awareness; and support for donor families.

6. Measure 1 of the national reform program included establishing the Australian Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Authority (OTA) in January 2009, as well as establishing DonateLife Agencies in each state to manage the donation process at the state level.7 OTA has overall national responsibility for the implementation of the nine COAG reform measures, working in collaboration with state and territory (state) based DonateLife8 Agencies.

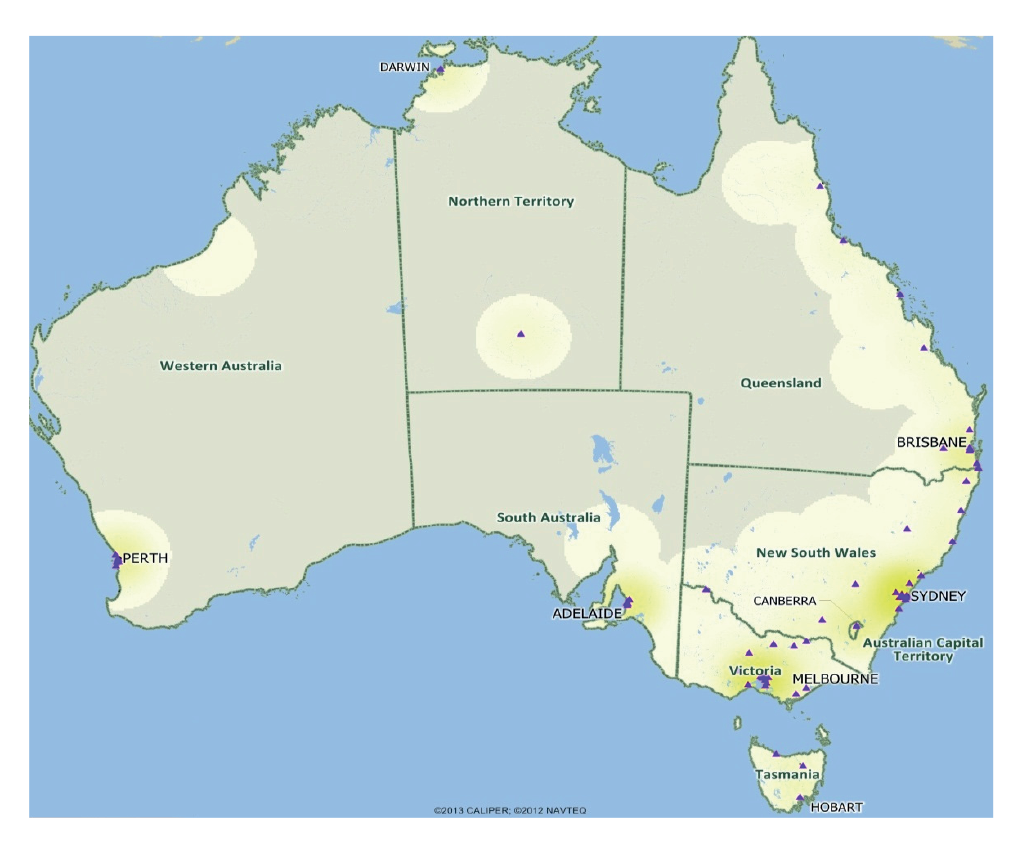

7. OTA administers Australian Government funding to each state government to employ DonateLife staff in 72 hospitals9 and eight DonateLife Agencies; which together with OTA comprise the DonateLife Network. At the end of June 2014, the DonateLife Network included: 175 hospital-based medical and nursing specialists in organ and tissue donation; and 100 staff (principally specialist nurses) in the eight DonateLife Agencies.

Audit objective and scope

8. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of OTA’s administration of community awareness, professional education and donor family support activities intended to increase organ and tissue donation.

9. The high-level criteria developed to assist in evaluating OTA’s performance relating to the administration of the community awareness, professional education and donor family support activities were that OTA:

- plans and designs targeted activities;

- effectively administers activities in accordance with relevant frameworks10; and

- assesses and reports on the effectiveness of activities.

10. The audit scope included an assessment of OTA’s role in delivering Measures 4, 5 and 6 of the national reform program. For Measure 4, the audit focussed on OTA’s Professional Education Package. The audit did not assess: the six remaining measures; the Department of Human Services’ administration of the Australian Organ Donor Register (AODR); or state and territory responsibilities under the national reform program.

Overall conclusion

11. The Australian Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Authority (OTA) is responsible for leading the implementation of the national reform program for organ and tissue donation, endorsed by COAG in 2008. The reform program comprises nine measures intended to introduce a nationally consistent approach for organ and tissue donation within a sector which has historically been state-based, and its successful implementation requires collaboration and consultation between OTA and key government and non-government stakeholders. The focus of this audit was on the measures relating to: professional awareness and education (Measure 4); coordinated and ongoing community awareness and education (Measure 5); and support for donor families (Measure 6).

12. Overall, OTA has made reasonable progress in implementing Measures 4, 5 and 6 of the national reform program, including the introduction of a Professional Education Package and National Donor Family Support Service (NDFSS). OTA has also undertaken a range of initiatives aimed at increasing community awareness and education about organ and tissue donation and transplantation. Of particular note is OTA’s approach to engaging with culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities, which has been consultative and informed by relevant research. Similarly, OTA adopted an evidence-based approach to selecting the key message for its $13.8 million national advertising campaign conducted from 2010 to 2012, which tracking research indicated achieved good outcomes against campaign benchmarks in its first phase. However, a key shortcoming across the three reform measures examined in this audit was the absence of suitable performance indicators and related targets to help assess the effectiveness of initiatives. Further, in relation to Measures 5 and 6, the audit identified opportunities for OTA to: more actively facilitate collaboration among key stakeholders; improve the transparency of its grants administration; and improve the consistency of support provided to donor families.

13. Under Measure 4 (Professional awareness and education), OTA introduced a Professional Education Package (the Package) in 2012. The Package incorporated an existing training program, the Australasian Donor Awareness Program11, as well as new Family Donation Conversation (FDC) Workshops. Since the introduction of the Package, there have been over 2000 training participants. At the time of the audit, the Package was being revised, and there would be benefit in OTA continuing to monitor the ongoing effectiveness and reach of the Package by introducing relevant internal performance indicators. OTA can also improve the consistency of the application of the FDC training by confirming which family consent request model should be adopted nationally, and promoting the application of this model through the FDC Workshops.

14. As part of its implementation of Measure 5 (Community awareness and education), OTA introduced a National Community Awareness and Education Program. The program aims to promote the principles of a nationally consistent and coordinated approach within the organ and tissue donation sector to community awareness and education. While there has been a high take-up of these principles among key community organisation stakeholders, there is scope for OTA to more actively facilitate collaboration between stakeholders so as to extend the reach of community awareness and education activities. The largest financial component of the National Community Awareness and Education Program was an advertising campaign conducted by OTA. Tracking research indicated that Phase 1 of the campaign (at a cost of $9.2 million) achieved improved outcomes against the campaign benchmarks, while Phase 2 (at a cost of $4.6 million) delivered a more marginal return on investment, serving largely to help maintain the outcomes of Phase 1.

15. OTA has also introduced a range of activities and resources as part of the National Community Awareness and Education Program, including the Community Awareness Grants program which distributes approximately $500 000 per annum to grant recipients for community awareness and education activities. However, OTA’s grants guidelines do not fully outline its grants assessment process, and the ANAO identified an application which was not funded as part of a competitive grant round, but which received funding from OTA as part of an unsolicited application process. OTA can improve the transparency and equity of its granting activity by reviewing its grants administration and in particular, informing potential grant funding applicants of all sources of available grant funding and the assessment process applying to these sources.

16. As part of its implementation of Measure 6 (Support for donor families) of the national reform program, OTA introduced the National Donor Family Support Service (NDFSS) in 2011, an initiative which included revised donor family support materials and funding to the states for Donor Family Support Coordinators (DFSCs). A national study of donor family experiences during 2010 and 2011, commissioned by OTA and released in 2014, indicates that there is scope to improve the level of support for donor families, both in the hospital setting and after a donation has occurred. The introduction of specific internal performance measures would help OTA assess effectiveness and provide greater assurance that donor families are receiving consistent levels of support across Australia.

17. The ANAO has made three recommendations aimed at: improving stakeholder engagement; reviewing OTA’s grants administration; and improving donor family support services.

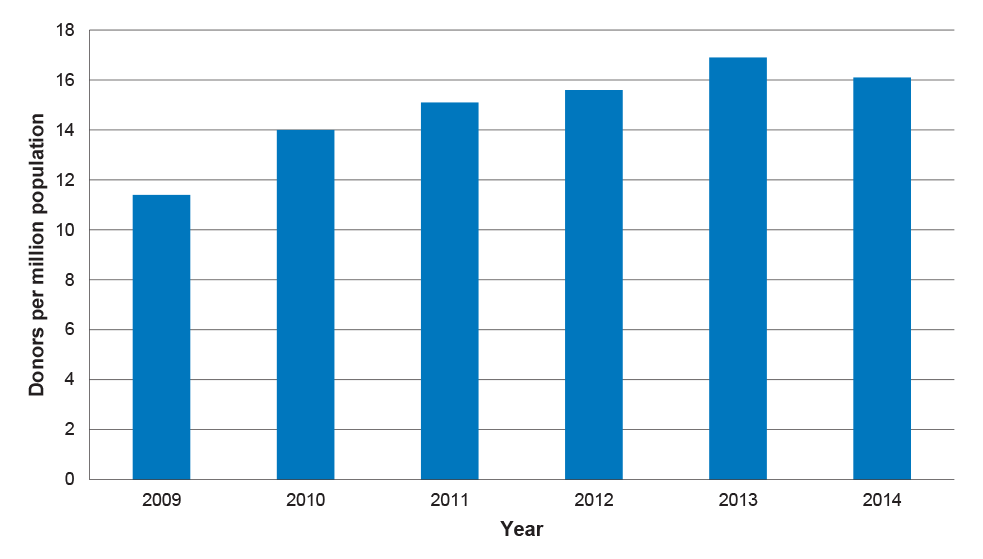

Key findings by chapter

Professional Education (Chapter 2)

18. Measure 4 of the national reform program required OTA to coordinate an ongoing, nationally consistent and targeted program of professional development and training for clinicians and care workers involved in organ and tissue donation. To this end, OTA introduced the Professional Education Package (the Package) in 2012 which incorporated an existing training program, the Australasian Donor Awareness Program, and two new workshops, a core and practical Family Donation Conversation (FDC) Workshop.12

19. To develop the FDC training, OTA first engaged an Australian training provider in April 2011. Participant feedback on the pilot training delivered by the provider in October 2011 indicated that it did not adequately reflect a clinical environment and consequently did not fully meet OTA’s requirements. Consequently, the training materials were revised by DonateLife clinical subject experts in 2011–12 to become the practical FDC Workshop, introduced in 2012.

20. In June 2011, OTA also engaged a United States training provider, the Gift of Life Institute, which OTA advised was the only known organisation with experience in specific organ donation consent request training. The Institute was required to revise and deliver its consent request training. This training became the core FDC Workshop and was first delivered in March 2012—one year after the planned delivery for the FDC training. Since its introduction, the workshop has been revised based on feedback from participants, as well as professional bodies.

21. In response to a decline in the number of deceased organ donors in 2014, OTA advised the Senate Community Affairs Legislation Committee in February 2015 that there was a clear difference in family consent outcomes when a trained requestor discussed organ donation with families and when an intensivist13 discussed donation with families. OTA acknowledged that it needed to reinforce its expectation that relevant staff undertake the FDC training and adopt the FDC model when seeking consent from families. While the FDC Workshops promote the collaborative requesting model14, it was only used in 16 per cent of cases where consent was sought from families for donation in 2013. However, OTA advised the ANAO that it did not expect the FDC Workshop participants to apply the collaborative requesting model as it had not yet been selected as the national model, and OTA is currently conducting a trial of the collaborative approach and another model, the designated requestor model, in select hospitals.15 The results of the trial, which is expected to be finalised in June 2015, will help OTA select the model to be adopted nationally. Confirming which model will be adopted nationally should improve the consistency of approach used to seek consent from families by enabling OTA to promote and monitor its application nationally through the DonateLife Network.

22. There would also be benefit in OTA continuing to monitor opportunities to improve the FDC Workshops in light of feedback from donor families, training participants and the state-based DonateLife Agencies. For example, national studies of donor family experiences have provided an indication of areas the FDC Workshops may need to address, such as the clarity of language used by medical staff. The introduction of internal performance indicators, such as the consistency of approaches towards donor families, would assist with assessing the effectiveness and reach of the Package, as no indicators are currently in place.

Community Awareness and Education (Chapter 3)

23. OTA introduced a National Community Awareness and Education Program, as required under Measure 5 of the national reform program. The Program: included a National Communications Framework and Charter aimed at establishing a nationally consistent and coordinated approach to community awareness and education; and aims to provide stakeholders with access to information and resources.

24. There has been a high take-up of key elements of the Charter among the 13 community organisations which were signatories to the Charter. While OTA provides a range of forums for stakeholders to collaborate and share information, the effectiveness of its key forum, the Charter Signatories Committee, appears to have diminished over time. Well established forums, such as the Charter Signatories Committee, can provide a valuable opportunity for ongoing consultation and collaboration with stakeholders, and OTA could usefully reflect on how best to harness this potential going forward.

25. The largest financial component of the Program was an advertising campaign conducted by OTA from 2010 to 2012, at a cost of $13.8 million. OTA adopted an evidence-based approach to selecting a campaign message, which focussed on promoting family discussion about organ and tissue donation. To assess the effectiveness of the advertising campaign, OTA commissioned tracking research to monitor outcomes against key campaign benchmarks.16

26. The tracking research for Phase 1 of the campaign indicated that while there had been an overall increase in family discussion levels, males and people aged 18 to 29 years old and over 65 years old were less likely to have discussed their donation wishes. The final wave of research for Phase 2 of the campaign indicated that there was still potential to improve the knowledge and awareness of people aged 18 to 29 years old as they were the most likely to be influenced by the campaign but also the least likely to have seen the advertising. In summary, the tracking research indicated that Phase 1 of the campaign (at a cost of $9.2 million) achieved improved outcomes against the campaign benchmarks, while Phase 2 (at a cost of $4.6 million) delivered a more marginal return on investment, serving largely to help maintain the outcomes of Phase 1.

27. Consistent with the Guidelines on Information and Advertising Campaigns by Australian Government Departments and Agencies (March 2010), OTA: tested the advertising materials with focus groups; submitted the relevant information to the Independent Communications Committee; and completed internal evaluations of each phase of the campaign.

28. OTA has conducted eight Community Awareness Grants Rounds, which are promoted as competitive rounds for the provision of Australian Government financial assistance. The transparency of OTA’s grants administration can be improved by more clearly outlining the grants assessment process in the guidelines for applicants. For example, OTA advised the ANAO that it reconsiders applications which have equal scores in light of points of difference and this can result in a further assessment of value for money. Further, scope, reach and impact are all components of assessing value for money, but this is not reflected in OTA’s grants guidelines. OTA also provides funding to organisations through an unsolicited application process, which is not documented on OTA’s website or in the grant guidelines. The ANAO identified one applicant that was unsuccessful in a competitive grant round but subsequently received funding for the same activity as an unsolicited application. To improve equity and transparency, OTA should review its grants administration with a focus on informing potential grant funding applicants of all sources of available funding and the assessment process applying to these sources.

29. OTA is responsible for leading and coordinating an annual national awareness week, known as DonateLife Week. OTA advised the ANAO that the focus for the week is primarily a media and public relations campaign which is supported by sector-driven activities as a secondary focus. OTA commissioned media analysis of the 2014 DonateLife Week which indicated that events during the week can be very effective at generating media attention. At present, DonateLife Week events occur in limited locations and there is scope for OTA to encourage a broader geographic reach and range of events, which may assist in generating additional media interest during DonateLife Weeks. In particular, there would be benefit from OTA encouraging greater participation in DonateLife Week by non-government stakeholders. Introducing broad targets for the level of activity undertaken by corporate and community supporters, in the same manner as it does for social media, may assist OTA to focus efforts on increasing the number and reach of activities hosted by supporters.

30. OTA has developed a range of educational resources, including specific resources targeted at CALD communities, which have been identified by research commissioned by OTA as a priority group. OTA undertook extensive consultation with faith and cultural leaders to develop a collection of published statements of support for organ and tissue donation, as well as translated videos and brochures. Planning is underway to produce a second wave of resources aimed at addressing identified misconceptions about organ and tissue donation that are specific to faith and cultural communities.

31. OTA identified in its National Communication Strategy 2013–14 four performance indicators to measure the effectiveness of the National Community Awareness and Education Program. For 2013, in relation to the four performance indicators, OTA:

- met the target for: Australians have had a family discussion about organ and tissue donation (achieved 75 per cent against a 70 per cent target);

- did not meet the targets for the two indicators of: Australians knowing their family members’ wishes (achieved 53 per cent against a 68 per cent target); and Australians understanding that family consent is required for donation to proceed (achieved 70 per cent against a 74 per cent target)17; and

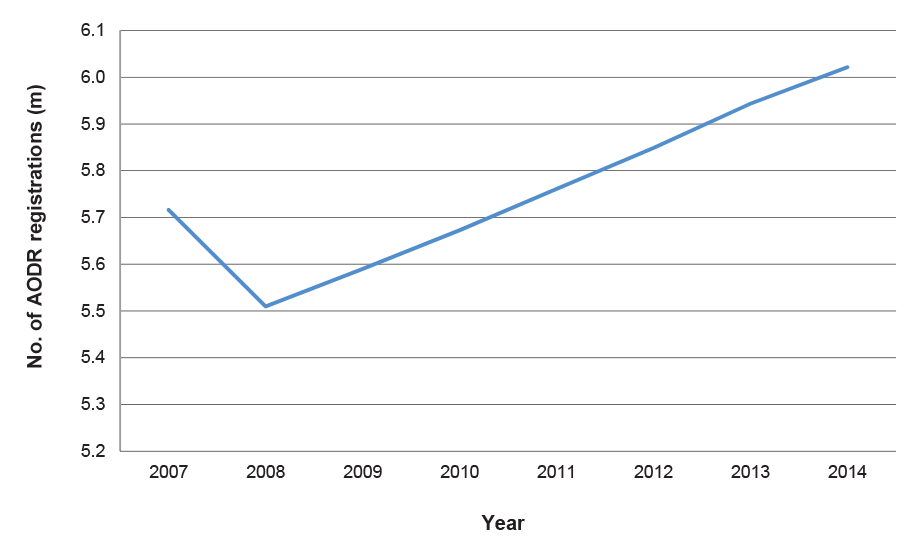

- achieved a 1.3 per cent increase in the number of registrations on the AODR.18

Support for Donor Families (Chapter 4)

32. Under Measure 6 of the national reform program, OTA introduced the National Donor Family Support Service (NDFSS) in 2011 to provide a tailored and nationally consistent program of support for donor families.

33. To implement the NDFSS, OTA provides funding to the states for Donor Family Support Coordinators (DFSCs). OTA revised a range of information resources for families and developed guidelines for DFSCs and Donation Specialist Coordinators on how to provide donor family support post-donation. At present, the guidelines do not outline the type of support to be provided to families in the hospital setting and should be enhanced to provide this guidance. Further, while the guidelines outline the type of support families should be provided post-donation, a national study of donor family experiences during 2010 and 2011 and released in 2014, indicated that there were varying levels of support being provided to donor families. For example, while DonateLife Agencies are required to contact donor families within 24 to 36 hours of donation, 22 per cent of family members did not receive a phone call following donation.19

34. To assess the effectiveness of support for donor families, OTA had two performance indicators in place which were discontinued in 2012–13.20 OTA reported in its annual report that it had met these indicators. However, ANAO analysis indicated that the basis for measuring achievement against the first performance indicator was too narrow to support an assessment that the indicator had been met. Further, OTA had collected insufficient information from DonateLife Agencies to inform an assessment of achievement against the second indicator. There have been no new indicators introduced to date, and consequently, OTA is not in a position to assess the implementation of Measure 6, relating to support for donor families. As a starting point, OTA should develop internal performance indicators to help assess the effectiveness of donor family support services.

Measurement and reporting (Chapter 5)

35. Consistent with the national reform program, OTA introduced a national data collection tool, known as the DonateLife Audit21, to assess state and national potential for organ donation rates, identify missed donation opportunities and determine the overall consent rate for organ donation. This information complements the Australia and New Zealand Organ Donation (ANZOD) Registry by providing data about hospital deaths in the context of organ donation.

36. The DonateLife Audit is limited to the DonateLife Network and does not collect information about eye and tissue donation.22 Further, while the DonateLife Audit reports information on organ donation after brain death (DBD), it does not report information about donation after circulatory death (DCD). This limits OTA’s capacity to report on the total number of potential donors, the donor family request rate and the consent rate. OTA is planning to develop a definition of the circumstances that will determine a potential DCD donor, which no country has yet developed, to improve consistency in capturing information about potential DCD donors. OTA’s planned enhancements will further improve the usefulness of the information collected through the DonateLife Audit.

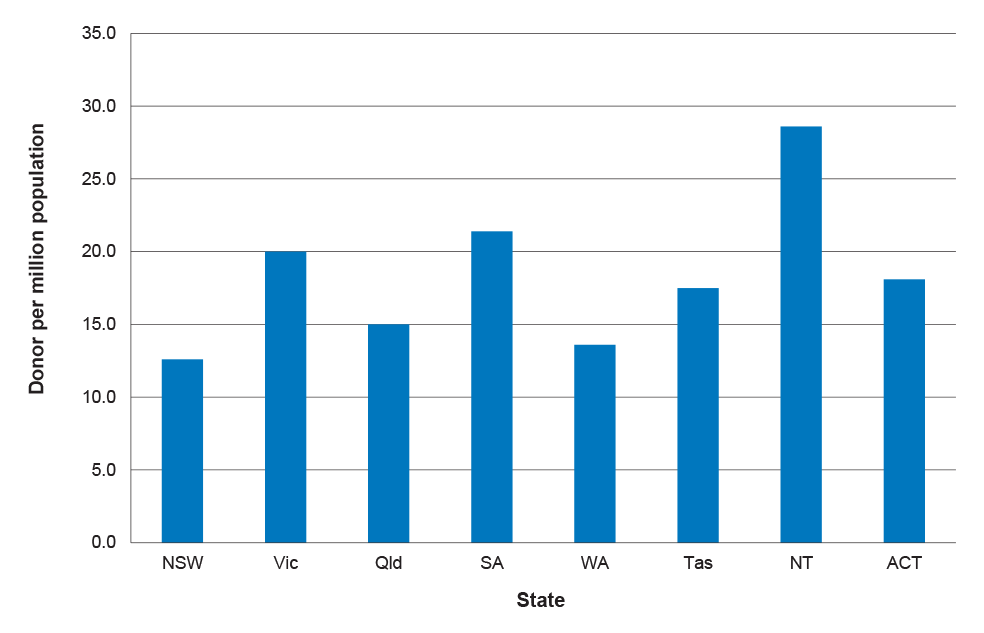

37. OTA’s annual reports indicate that performance against indicators such as deceased donors per million population (dpmp) and number of donors has improved since the commencement of the national reform program, but decreased slightly in 2014.23 However, OTA is not achieving the targets set for the program’s quantitative performance indicators: donor family request rate and donor family consent rate.24 OTA advised the Senate Community Affairs Legislation Committee in February 2015 that the decline was partly attributable to the variability of donation outcomes between states and territories. OTA also highlighted a lack of consistency between states and territories in applying the Family Donation Conversation training, which OTA considered had adversely affected the family consent rate.

38. Since 2010, OTA has published on its website six-monthly performance reports on the implementation of the national reform program. The performance reports include information on the number of organ and tissue donors, number of transplant recipients and number of organs transplanted. OTA advised the ANAO that, in the future, these reports will only be prepared on an annual basis and the need for periodic reports will be assessed taking into account agency resources and priorities. The reports prepared to date do not include information about the number of registrations on the AODR. To provide a holistic view of the impact of the national reform program, there would be merit in OTA including the number of registrations in its performance reports.

Summary of entity response

39. The proposed audit report was provided to the Australian Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Authority (OTA). OTA’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, while the full response is provided at Appendix 1.

The aim of the Australian Government’s national reform programme is to implement a nationally coordinated world’s best practice approach to organ and tissue donation for transplantation in collaboration with the states and territories, clinicians and the community sector. Organ donation is a rare event, only around 1-2% of people who die in hospitals, die in the specific circumstances required to be a potential organ donor.

The Organ and Tissue Authority (OTA) thanks the generous Australians and their families who save and transform the lives of transplant recipients through organ and tissue donation.

The OTA notes the audit report’s conclusions and agrees with the recommendations of the proposed report.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Para 3.13 |

To better harness the capacity of the organ and tissue donation sector and extend the reach of community awareness and education activities, the ANAO recommends that OTA more actively facilitate collaboration between Charter signatories through established forums. OTA response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Para 3.52 |

To improve transparency and equity, the ANAO recommends that OTA review its grants administration, with a particular focus on informing potential applicants of all available sources of grant funding and the assessment process applying to each source. OTA response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.3 Para 4.26 |

To improve the services provided to donor families, including those families for which consent is provided but donation does not proceed, the ANAO recommends that OTA:

OTA response: Part (a): Agreed. Part (b): Agreed, subject to consultation with state and territory governments. |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the Australian Government’s national reform program to increase the rate of organ and tissue donation. It also provides an outline of the audit objective, criteria and approach.

Background

1.1 Australia’s rate of organ and tissue donation does not meet the current demand for transplantation. In 2014, an average of 1632 people were on organ transplant waiting lists each month, and in total, 1117 people received organ transplants. In the same year, 5553 people received tissue transplants.

1.2 To increase Australia’s national performance in organ and tissue donation, the then Australian Government established the National Clinical Taskforce on Organ and Tissue Donation (the Taskforce) in October 2006. The Taskforce was asked to provide evidence-based advice on ways to increase the rate of organ and tissue donation with a view to informing the prospective reform agenda.25 The final report, submitted by the Taskforce to the Government in January 2008, identified systemic problems with the Australian organ donation and transplantation sector and made 51 recommendations to improve the performance of Australia’s donation and transplantation system.

National reform program

1.3 On 2 July 2008, the Australian Government announced a national reform program to ‘establish Australia as a world leader in organ donation for transplantation’.26 Endorsed by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), the national reform program committed $136.4 million in new Australian Government funding over four years (2008–2012) to improve access to transplants through a nationally coordinated approach to organ and tissue donation.

1.4 The national reform program had two objectives: to increase the capability and capacity within the health system to maximise donation rates; and raise community awareness and stakeholder engagement across Australia to promote organ and tissue donation. Nine measures were endorsed by COAG aimed at achieving the two broad program objectives:

- Measure 1: A new national approach and system – a national authority27 and network of organ procurement organisations.

- Measure 2: Specialist hospital staff and systems dedicated to organ donation.

- Measure 3: New funding for hospitals.

- Measure 4: National professional awareness and education.

- Measure 5: Coordinated ongoing community awareness and education.

- Measure 6: Support for donor families.

- Measure 7: Safe, equitable and transparent national transplantation process.

- Measure 8: National eye and tissue donation and transplantation.

- Measure 9: Additional national initiatives, including living donation programs.

1.5 This audit focussed on Measures 4 to 6 highlighted above, relating to: professional education; community awareness; and support for donor families.

Professional awareness and education (Measure 4)

1.6 Measure 4 of the national reform program is intended to facilitate ongoing development and training for clinical and professional staff involved in organ and tissue donation. The measure is expected to drive cultural and organisational change in public and private hospitals and contribute to the front-end clinical work of increasing donation and transplantation rates.

Community awareness and education (Measure 5)

1.7 Measure 5 aims to increase public knowledge about organ and tissue donation and build confidence in Australia’s donation system. The provision of nationally consistent information about organ and tissue donation is expected to contribute to an increase the number of families consenting to donation.

Support for donor families (Measure 6)

1.8 Measure 6 provides for a nationally coordinated approach to support the families of deceased donors. New funding was provided for the development of a national donor family support program so that donor families receive the support they need in the hospital setting and afterwards.

Organ donation in Australia

1.9 The Australian organ and tissue donation system is based on an ‘informed consent’ (or opt-in) model, whereby individuals agree to donate their organs and tissue in the event of their death.28 The Australian Organ Donor Register (AODR), administered by the Department of Human Services, enables individuals to record their consent or objection to becoming an organ and/or tissue donor. As at 31 January 2015, there were approximately six million registrations on the AODR.29

1.10 Regardless of whether an individual has provided consent for donation, the practice in Australia is to also seek agreement from a donor’s next of kin before donation proceeds.30 The Australian Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Authority (OTA) reported in its 2014 performance report that in 2014, there were approximately 700 potential donors and 680 requests were made to their next of kin for organ and tissue donation to proceed. Of these requests, consent was given in 61 per cent of cases. This resulted in the transplantation of 1193 organs, as a number of organs can be donated by each donor.

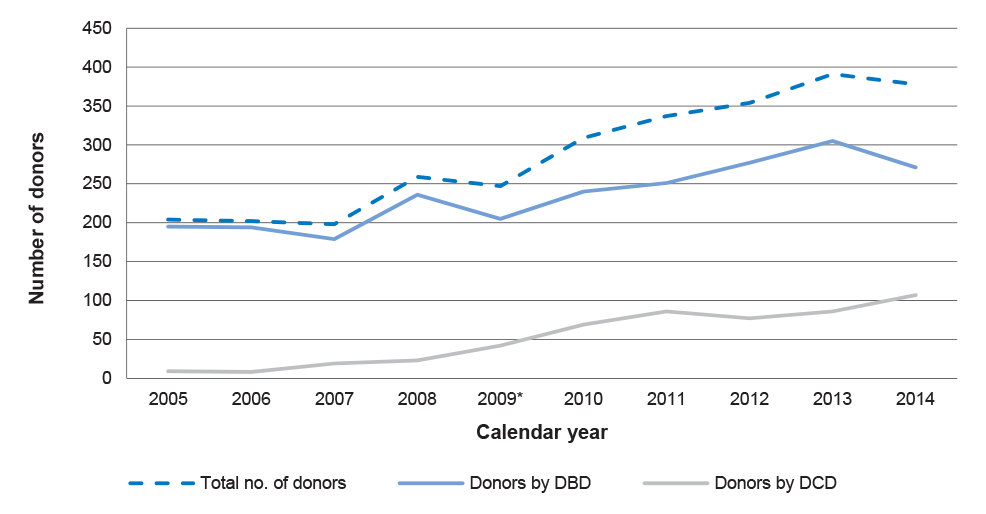

1.11 The number of deceased donors per million population (dpmp) is the most common measure used for international comparisons of performance in organ and tissue donation. In the decade prior to the launch of the national reform program in 2008–09, Australia’s donor rate remained relatively constant at around 10 dpmp. This figure rose to 16.9 dpmp in 2013 and then decreased slightly to 16.1 in 2014.31

The Australian Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Authority

1.12 OTA was established in January 2009 as the first measure of the national reform program. OTA was intended to lead a coordinated national approach to organ and tissue donation in partnership with the states and territories (states), clinicians and the community sector. Operating under the Australian Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Authority Act 2008, OTA is an independent statutory authority within the Department of Health portfolio.32

1.13 At 30 June 2014, OTA employed 26.2 full-time equivalent staff, including a Chief Executive Officer and one Senior Executive Service officer. A three-tier committee structure is in place to provide program governance and sector-specific advice. OTA reports publicly on the implementation of the national reform program, as well as broader measures associated with organ and tissue donation, in performance reports33 and through its annual report.

1.14 The Australian Government announced on 13 May 2014 that OTA would merge with the National Blood Authority by 1 July 2015.

DonateLife Network

1.15 OTA has overall national responsibility for the implementation of the nine COAG reform measures, working in collaboration with state and territory based DonateLife34 Agencies. Under Measure 1 of the national reform program, DonateLife Agencies were established in each state to manage the donation process at the state level. Led by their respective State Medical Directors and a National Medical Director, DonateLife Agencies are responsible for the coordination of organ and tissue donations, professional and clinical education, support for donor families, community awareness and data collection.

1.16 OTA provides Australian Government funding to each state government to employ DonateLife staff in 72 hospitals35 and the DonateLife Agencies. At the end of June 2014, the DonateLife Network included 175 hospital-based medical and nursing specialists in organ and tissue donation and 100 staff (principally specialist nurses) in the eight DonateLife Agencies. The National Roles and Responsibility Guidelines36, developed by OTA in consultation with the state governments, inform the recruitment of DonateLife staff.

1.17 Funding to the states is provided through two-year funding agreements which require each jurisdiction to maintain an organ and tissue donation service delivery model consistent with the national reform approach and in accordance with relevant ethical guidelines and clinical protocols.37 Funding agreements include an agreed performance and reporting framework to enable OTA to monitor progress in each jurisdiction.

Organ and Tissue Donation Reform Package: Mid-Point Implementation Review

1.18 In 2011, the then Parliamentary Secretary for Health and Ageing commissioned a review of the implementation of the national reform program—the Organ and Tissue Donation Reform Package: Mid-Point Implementation Review Report. Overall, the review found that while significant progress had been achieved for some measures, only moderate or relatively little progress had been made in implementing the remaining measures.38 The report observed that OTA had made significant progress in establishing the DonateLife Network and supporting the placement of dedicated clinical staff in hospitals.

1.19 The report identified a number of areas for improvement, including: strengthening clinical practice improvement programs and establishing a clinical governance framework; enhancing national performance measurement; and expanding professional education for the DonateLife Network and broader hospital staff. A focus on these areas is reflected in OTA’s strategic priorities going forward, as agreed between the Australian and state governments.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.20 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of OTA’s administration of community awareness, professional education and donor family support activities intended to increase organ and tissue donation.

1.21 To assist in evaluating OTA’s performance in terms of the audit objective, the ANAO developed the following high-level criteria relating to the administration of community awareness, professional education and donor family support activities:

- OTA plans and designs targeted activities;

- OTA effectively administers activities in accordance with relevant frameworks39; and

- OTA assesses and reports on the effectiveness of activities.

1.22 The audit scope included an assessment of OTA’s performance in relation to Measures 4, 5 and 6 of the national reform program.40 For Measure 4, the audit focussed on OTA’s Professional Education Package. The audit did not assess: the other six reform measures; the Department of Human Services’ administration of the AODR; or the legislation and policy regulating organ and tissue donation in Australia.

Audit methodology

1.23 The ANAO’s audit methodology included:

- interviewing:

- relevant OTA staff, including State Medical Directors and a number of DonateLife Agency staff; and

- stakeholders, including non-government organisations; and

- reviewing:

- advertising, awareness raising and professional education materials and associated evaluation results;

- compliance with the Australian Government’s 2010 Guidelines on Information and Advertising Campaigns by Australian Government Departments and Agencies;

- compliance with the July 2009 and July 2013 Commonwealth Grant Guidelines; and

- relevant performance measurement and reporting material.

1.24 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $393 588.

Structure of report

1.25 The structure of the audit report is outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Structure of chapters

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

2. Professional Education |

Examines OTA’s Professional Education Package, including the development of the Family Donation Conversation Workshops. |

|

3. Community Awareness and Education |

Examines the management and effectiveness of OTA’s Community Awareness and Education Program. |

|

4. Support for Donor Families |

Examines the donor family support resources and services funded by OTA. |

|

5. Measurement and Reporting |

Examines OTA’s internal and external reporting, including its key performance indicators. |

2. Professional Education

This chapter examines OTA’s Professional Education Package, including the development of the Family Donation Conversation Workshops.

Introduction

2.1 Under Measure 4 of the national reform program, OTA is required to coordinate an ongoing, nationally consistent and targeted program of professional development and training for clinicians and care workers involved in organ and tissue donation. The program, which includes OTA’s Professional Education Package (the Package), is expected to build on existing programs, including the Australasian Donor Awareness Program (refer to paragraphs 2.3 to 2.8).

2.2 OTA introduced the Package in 2012.41 Initially the Package included two Australasian Donor Awareness Program workshops and two Family Donation Conversation (FDC) Workshops—one core and one practical.42 OTA was revising the Package during this audit, to include: an Introductory Donation Awareness Training workshop; the two FDC Workshops; and advanced training to focus on current issues.43

Australasian Donor Awareness Program

2.3 The Australasian Donor Awareness Program has been delivered in Australia since 1994 and is intended to provide participants with a greater understanding of organ and tissue donation and the skills to sensitively conduct conversations with families about organ and tissue donation. The workshops are aimed at staff involved in end-of-life care, including intensivists.44 The program was managed by the Australian Red Cross Service until OTA assumed responsibility on 30 June 2010.

2.4 As part of the Australasian Donor Awareness Program, OTA delivered an ongoing training schedule comprising two workshops:

- general workshops: designed for registered nurses from critical care, emergency and operating theatres, allied health and palliative care professionals, social workers, chaplains and pastoral care workers; and

- medical workshops: designed for intensivists and trainees in intensive and emergency medicine, and intended to provide an overview of the organ and tissue donation process and information on communicating with and caring for families.

2.5 The program was revised following a review of the Professional Education Package by OTA in 2013, which identified some duplication with the training provided by the College of Intensive Care Medicine (CICM). From July 2014, the medical workshop was discontinued and its key grief and bereavement components were included in the core FDC Workshop, discussed in the next section.

2.6 The remaining general workshop will be replaced with an Introductory Donation Awareness Training workshop, which is currently being developed. The introductory workshop will provide a general overview of organ and tissue donation to DonateLife Network staff, hospital-based staff and students. OTA advised the ANAO that it has rescheduled the introduction of the introductory workshop from July 2014 to May 2015.

2.7 In its annual report, OTA does not report on the number of participants who have attended the Australasian Donor Awareness Program training. However, in its March 2014 report to the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, OTA reported that 67 workshops had been held with over 1000 participants since the introduction of the Professional Education Package in 2012.45

2.8 OTA does not have internal performance indicators to assess the effectiveness of the Australasian Donor Awareness Program. There would be benefit in OTA introducing internal performance indicators for the Introductory Donation Awareness Training workshop, following its launch, to measure and assess its effectiveness and reach.

Family Donation Conversation Workshops

2.9 The FDC Workshops were introduced in 2012 as part of OTA’s Professional Education Package. They are directed to health professionals and are a means for promoting a nationally consistent and best practice approach to requesting consent for donation from potential donors’ next of kin, and to assist families to make a decision in relation to organ and tissue donation. The introduction of the workshops was considered necessary as practices varied between states and in some instances between hospitals in the same state.

Development of the workshops

2.10 OTA engaged an Australian training provider in April 2011 to develop family donation conversation training: one concise module to be integrated into the Australasian Donor Awareness Program; and a comprehensive one-day workshop.46 The purpose of the workshops was to provide participants with the skills to inform families about donation and support them to make a donation decision.

2.11 A pilot of the one-day workshop developed by the Australian provider was held in October 2011. Participant feedback on the pilot indicated that it did not adequately reflect a clinical environment and therefore, did not meet OTA’s requirements. Consequently, the training materials were provided to a group of DonateLife clinical subject experts in 2011 to finalise. The materials comprise the basis for the current practical FDC Workshop (refer to paragraph 2.2).

2.12 In June 2011, OTA also engaged a United States training provider, the Gift Of Life Institute (the Institute), to deliver two of its training workshops in Australia.47 OTA understood that the Institute was the only known organisation with a request for consent training module and advised the ANAO that the Institute’s workshops were expected to provide an advanced level of training for clinicians, whereas the training being developed by the Australian provider was expected to provide practical training on communicating sensitively.

2.13 The Institute delivered two of its workshops under its first contract.48 Based on this material, the Institute was engaged under a second contract to develop and deliver a revised workshop, as well as train DonateLife Network staff to deliver the workshop.49

Delivery of the workshops

2.14 The FDC Workshops commenced in March 2012—one year after the planned delivery date. Since the core FDC Workshops were introduced across all states in 2012, OTA has reported that:

- 30 core FDC Workshops have been held, with more than 700 participants; and

- 35 practical FDC Workshops have been delivered to 401 participants.

2.15 The Institute prepared two reports based on the training it delivered across six states during March and May 2012. The reports identified some areas for improvement in the training, which the Institute implemented.50

2.16 The FDC Workshops promote a consistent model for requesting consent for donation from families, known as the collaborative requesting model.51 The reports concluded that in some workshops, there was a lack of acceptance from participants about the need to change the family consent request approach. There were also concerns raised by participants regarding the proposed change in their roles and that the collaborative requesting model was potentially coercive. Overall, the second report noted that the participants did not have a clear understanding of the initiatives being progressed by OTA, including the change in consent request approach.

2.17 OTA and the Institute revised the FDC materials between September 2013 and August 2014, to incorporate the family communication elements from the discontinued medical Australasian Donor Awareness Program workshop.52 The revised FDC Workshop was delivered as a pilot in March 2014. The Institute prepared a further report about the pilot and did not recommend any further changes to the training.

2.18 The revised workshop was also delivered to the CICM and the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society in April 2014.53 Feedback from these bodies was that the training was an improvement on the previous iteration but that it could be further enhanced. Specific feedback regarding the wording and relevance of some materials was provided to OTA and this feedback was actioned, where OTA considered it appropriate.

2.19 There would be benefit in OTA continuing to monitor opportunities to improve the FDC Workshops. National studies of donor family experiences provide an indication of issues which the FDC Workshops may need to address further. For example, a national study of donor family experiences during 2010 and 2011 suggested that the language used by medical staff in discussion with families was an issue in some instances.54 Eighteen per cent of study participants only ‘somewhat’ agreed that the language used by medical staff was clear and easy to understand and 14 per cent of participants only ‘somewhat’ agreed that they had sufficient opportunity to ask questions.

2.20 There is also scope for OTA to consider introducing variations of the FDC Workshops to more effectively target the needs of staff involved in end-of-life patient care. In discussing the review of the Professional Education Package implemented in 2014, members of OTA’s Jurisdictional Advisory Group55 suggested that an abridged version of the FDC could be introduced for staff who are not involved in requesting consent but who are involved with supporting donor families.

Measurement of the workshops

2.21 OTA collects feedback from participants following the FDC Workshops. OTA advised the ANAO that feedback is reviewed by facilitators at the conclusion of the first day of training so that any issues or concerns are addressed on the second day. Further, OTA’s National Training Coordinator reviews feedback from each workshop and discusses any issues with facilitators and local DonateLife Agencies, if necessary. The Coordinator also provides feedback to OTA to be considered for review and so that feedback can be circulated to all facilitators.

2.22 As mentioned in paragraph 2.14, OTA reports on the number of FDC Workshop participants. However, OTA has not developed internal performance indicators for the FDC Workshops, to help assess their contribution to the professional training effort. Overall, the intended outcome of the Professional Education Package is to contribute to an increase in the family consent rate. There is scope for OTA to consider the applicability of internal performance indicators, such as the consistency of approaches towards donor families (refer to paragraphs 2.23 to 2.25).

Effectiveness of the workshops

2.23 Overall, the FDC Workshops are targeted at improving the family consent rate. In 2014, for the first year since the commencement of the national reform program, there was a decline in the number of deceased organ donors, which OTA has partly attributed to lower family consent rates in some states. OTA advised the Senate Community Affairs Legislation Committee in February 2015 that there was a clear difference in family consent outcomes when a trained requester discussed organ donation with families and when an intensivist discussed donation with families. To address variability in family consent rates, OTA acknowledged that it needed to reinforce its expectation that relevant staff undertake the FDC training and apply the training when seeking consent from families.

2.24 The FDC Workshops were introduced to promote a nationally consistent and best practice approach to requesting consent from families. As discussed in paragraph 2.16, the FDC Workshops promote the collaborative requesting model. The 2013 DonateLife Audit56 reported that in 61 per cent of cases where consent was sought from families for donation, the request was made by the treating intensivist, and a collaborative requesting model was used in only 16 per cent of cases.

2.25 However, OTA advised the ANAO that it did not expect the FDC Workshop participants to apply the collaborative requesting model as it had not yet been selected as the national model. OTA is currently conducting a trial of the collaborative approach and another model, the designated requestor model, in select hospitals.57 Based on the results of the trial, which is expected to be finalised in June 2015, and following consultation within the DonateLife Network and state governments, OTA will select the model to be adopted nationally. Confirming which model to adopt nationally will assist to improve the consistency of approaches to requesting consent from families as it will enable OTA to promote and monitor the application of the selected model within the DonateLife Network.

Conclusion

2.26 As required under Measure 4 of the national reform program, OTA introduced the Professional Education Package to address an identified gap in education. The Package incorporates the existing Australasian Donor Awareness Program, which is expected to be replaced by the Introductory Donation Awareness Training workshop in May 2015.

2.27 The Package also incorporates the core and practical FDC Workshops, which over 1100 participants have attended since they were introduced in 2012. However, there were some shortcomings with the development and delivery of the FDC Workshops; in particular, the engagement of a provider which did not fully meet OTA’s training requirements, and delays in the introduction of the Workshops.

2.28 In 2014, the number of deceased organ donors decreased slightly, which OTA has partly attributed to low family consent rates in some states. OTA acknowledged that it needed to reinforce its expectation that relevant staff undertake and apply the FDC training when seeking consent from families. Confirming which model to adopt nationally will enable OTA to promote and monitor the application of the selected model within the DonateLife Network and assist with improving the consistency of approaches to donor families.

2.29 Further, there would be merit in OTA continuing to assess the need for enhancements to the FDC Workshops, as well as to the Professional Education Package as a whole. There are no internal performance indicators relating to the Australasian Donor Awareness Program or FDC Workshops to help OTA assess their contribution to professional training. The introduction of internal performance indicators would assist with assessing the effectiveness and reach of the Professional Education Package.

3. Community Awareness and Education

This chapter examines the management and effectiveness of OTA’s Community Awareness and Education Program.

Introduction

3.1 To improve public knowledge about organ and tissue donation, Measure 5 of the COAG national reform program provided for coordinated and ongoing community awareness and education.58 The three key elements of Measure 5 are: a national community awareness framework; a national community awareness charter; and an ongoing national community awareness and education program.

3.2 OTA’s National Communication Framework and Charter form part of the National Community Awareness and Education Program, which has included a national advertising campaign running from 2010 to 2012. Other elements of the program are: a grants program; a national awareness week; information and education resources; community outreach; and media and public relations.

National Community Awareness and Education Program

3.3 The overall aim of OTA’s Community Awareness and Education Program is to contribute to increases in organ and tissue donation. OTA promotes a ‘Discover, Decide and Discuss’ message directed to the community:

- Discover: promote nationally consistent factual information about organ and tissue donation, the benefits of transplantation and the importance of family discussion and knowledge of each other’s donation decisions.

- Decide: encourage Australians to make an informed decision about becoming a potential donor and register their decision on the Australian Organ Donor Register (AODR).

- Discuss: increase the number of Australian families that discuss and know each other’s decisions on organ and tissue donation.

OTA’s communications framework

3.4 A National Communications Framework (the Framework) was developed by OTA in early 2009 in consultation with sector stakeholders to: establish the parameters of a nationally consistent and coordinated approach to community awareness and education; and provide stakeholders with access to useful information and resources.

3.5 In November 2009, OTA launched the DonateLife brand and website as part of a national communications platform for the organ and tissue sector. The DonateLife logo became the official symbol for organ and tissue donation in Australia, featuring in all materials developed by OTA. Stakeholders were also encouraged to use the DonateLife logo alongside their existing brand. The state organ and tissue donation agencies became the DonateLife Agencies and adopted the DonateLife name and brand. In establishing a social media presence, OTA created a DonateLife Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Twibbon identity to assist with community awareness and education.

3.6 OTA also introduced the National Communications Charter (the Charter), to encourage governments and stakeholders to sign up to best practice principles for community awareness, education and communication activities, including a commitment to use consistent language and messages. There has been a high take-up of key elements of the Charter among the 13 community organisations which were signatories to the Charter. For example, 90 per cent of the community organisation signatories use the national logo in their communications, in conjunction with their own branding.

3.7 In 2014, OTA developed a new DonateLife Stakeholder Engagement Framework to replace the National Communications Framework and Charter. The new framework incorporates three stakeholder tiers:

- DonateLife Partners are those who have organ and tissue donation for transplantation as part of their core business, including current Charter signatories;

- DonateLife Community Partners represent a range of sporting clubs, schools, small businesses and foundations who want to be associated with DonateLife but do not have organ and tissue donation or transplantation as their core business; and

- DonateLife Corporate Partners from the business sector seeking to promote and facilitate education and awareness of organ and tissue donation with their employee and customer base.

3.8 As at January 2015, OTA had 52 DonateLife Partners, 20 DonateLife Community Partners and five Corporate Partnerships. Each partner has signed a DonateLife Partnership Agreement, committing to the promotion and distribution of the DonateLife key messages and materials and use of the partner logo, in addition to organising a minimum of one community awareness activity per year.

3.9 The previous Framework outlined the responsibilities of the Australian Government and Charter signatories in relation to community awareness and education. The ANAO assessed the extent to which OTA has fulfilled its responsibilities under the Framework, with the results summarised in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: List of OTA’s responsibilities under the National Communications Framework

|

Responsibilities |

Status |

|

Provide communication materials and resources |

F |

|

Encourage the use of the national logo for organ and tissue donation |

F |

|

Make available publication quality logo kits |

F |

|

Maintain a dedicated website |

F |

|

Advise organisations where necessary on how to amend current activities to cater for the introduction of a new communications framework |

F |

|

Assist signatories in handling issues as they arise |

F |

|

Encourage and facilitate collaboration between signatories |

P |

|

Provide the opportunity to apply for funding for community awareness and education activities |

F |

Source: ANAO analysis and DonateLife National Communications Framework 2011.

Legend: F = fully met the responsibility.

P = partially met the responsibility.

3.10 Table 3.1 indicates that OTA has largely met its responsibilities under the Framework. However, there remains scope to more actively encourage and facilitate collaboration among Charter signatories. This is consistent with OTA’s obligations under the national reform program to develop a framework that encourages ‘stakeholders to collaborate and build on each other’s efforts and avoid unnecessary duplication of work, research and resources’.59

3.11 OTA advised the ANAO that it encourages collaboration and information sharing among Charter signatories through a range of mediums including committees, newsletters and emails. A key vehicle for collaboration is the Charter Signatories Committee, which is used for: OTA to update members on the progress of the national reform program, including the National Community Awareness and Education Program; and for Charter signatories to share their plans, demonstrate how they align with the national reform program and identify opportunities for sector participation. Information on events being planned by stakeholders is also shared at Charter Signatories Committee meetings and is included on a national calendar of events.60

3.12 While the Charter Signatories Committee was originally intended as a collaborative forum, its effectiveness in this respect appears to have diminished over time. The frequency of meetings has reduced from six-monthly to annually, and representatives from DonateLife Agencies have ceased attending meetings. Further, the minutes of meetings examined by the ANAO indicate that meetings now largely focus on the provision of information from OTA, with a lesser focus on identifying opportunities for collaboration. Established forums such as the Charter Signatories Committee provide a valuable opportunity for ongoing consultation and collaboration between OTA and stakeholders, and there would be merit in OTA reflecting on how best to harness this potential going forward.

Recommendation No.1

3.13 To better harness the capacity of the organ and tissue donation sector and extend the reach of community awareness and education activities, the ANAO recommends that OTA more actively facilitate collaboration between Charter signatories through established forums.

OTA’s response

3.14 Agreed.

Advertising campaign

3.15 Research undertaken in 200761 indicated that while over 90 per cent of Australians support organ and tissue donation, this level of support was not demonstrated in the proportion of actual donors. A number of factors can influence behaviour and attitudes in relation to organ and tissue donation, such as knowledge and beliefs about donation. This research and other research undertaken by two research agencies in 2009, informed OTA’s decision to focus its advertising effort on promoting family discussion about organ and tissue donation.

Campaign messaging and selection

3.16 OTA’s advertising campaign, ‘Discuss it today, OK’, was aimed at increasing awareness about the importance of family discussion among Australians. The campaign’s call to action, and the primary objective of the campaign, was for Australians to know, understand and accept the wishes of their family members by discussing organ and tissue donation and sharing their wishes with family members.

3.17 The primary target audience for the campaign was families as they are required to provide consent for organ donation to proceed. Three segments were identified within this primary target audience: people who were undecided about organ donation; people who had registered to be organ donors; and

non-registered donors who had decided to be organ donors.

3.18 To develop the campaign, OTA undertook a select tender process and approached five advertising agencies to provide submissions on a campaign which included: a television commercial, radio and print advertisements and internet banners.62 The campaigns proposed by the five agencies were tested by a research agency.63

3.19 The report issued by the research agency, summarising the results of the testing, advised that three of the five proposed campaigns had potential. However, the report noted that one of the proposed campaigns was a clear preference, and was recommended because each media component of the campaign (i.e. television and radio) tested well and contributed to a cohesive campaign. Further, the preferred campaign had the largest proportion of participants identifying it as their first choice among the tested campaigns. The tender evaluation panel, however, ranked OTA’s chosen campaign, ‘Discuss it today, OK’, higher than the recommended campaign following a value for money assessment.64

Campaign strategy

3.20 The campaign was undertaken in two phases at a cost of $13.8 million (refer to Table 3.2). Both phases were extended, with Phase 1 extended twice. These extensions were designed to supplement the primary phases of the campaign and to raise awareness during the 2011 and 2012 DonateLife Weeks. OTA commissioned an agency to undertake tracking research during the campaign to monitor its effectiveness65, and also used the results of the tracking research to inform the later phases of the campaign.

Table 3.2: Summary of campaign advertising phases

|

Phase |

Message |

Media channels |

Timeframe |

Cost 1 |

|

Phase 1 |

‘Discuss it today, OK’ |

Television, radio, magazines, outdoor, online and cinema |

May to June 2010 |

$6.4 million |

|

Extended Phase 1 |

‘Discuss it today, OK’ |

Online advertising and social video |

November 2010 to December 2011 |

$2.8 million |

|

Second extension of Phase 1 |

‘Any day is a good day to talk about it’ |

Television, print and online component |

February to May 2011 |

|

|

Phase 2 |

‘Know their wishes’ |

Television, print, online and outside advertising |

May to August 2011 |

$2.9 million |

|

Extended Phase 2 |

‘Know their wishes’ |

Television and online advertising |

February to April 2012 |

$1.7 million |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Note 1: These costs included: developing the campaign materials; purchasing media placements; producing and distributing materials; and undertaking the tracking research.

3.21 Phase 1 was launched with a call to action for family members to discuss their donation wishes—in effect for people to tell family members their wishes. This message was consistent with research undertaken in 2007 which showed that most respondents were in favour of a communications campaign that emphasised telling those close to them of their own wishes in relation to donation, rather than asking about the other person’s wishes (59 per cent and 30 per cent respectively). The tracking research results showed that Phase 1 of the campaign was effective at increasing: family discussion rates; awareness of family members’ wishes; and awareness that family consent is required for donation against benchmark levels (refer to paragraphs 3.31 to 3.36).66

3.22 The message for Phase 2 was developed in response to the tracking research, which showed that a higher proportion of people indicated that they had advised their family members of their donation wishes than the proportion of people who indicated they knew their family members’ donation wishes. Phase 2 focussed on the less popular message—to ‘ask’ family members about their wishes—in order to encourage people who were uncomfortable with initiating a discussion about organ and tissue donation. Overall, while the tracking research indicated that the Phase 2 campaign resulted in higher rates of discussion and awareness of the role of family consent, these outcomes were only marginally higher than those achieved in Phase 1 (refer to Table 3.3).

3.23 The second extension of Phase 1 and the extension of Phase 2 coincided with the 2011 and 2012 DonateLife Weeks. The message, ‘Any day is a good day to talk about it’ and associated advertising materials were specifically developed for the 2011 DonateLife Week. This revised message was expected to generate a sense of urgency for having the discussion about organ and tissue donation, as well as give people permission to initiate the discussion.

Testing

3.24 In addition to the testing outlined in paragraphs 3.18 to 3.19, OTA commissioned testing of revised campaign materials, consistent with the Australian Government’s campaign advertising guidelines then in effect (the advertising guidelines).67 This testing was conducted by the research agency which had earlier advised OTA, and was intended to provide assurance that the advertising messages were clear and that the advertisements had an impact across different demographics.

3.25 The Phase 1 campaign materials were tested four times. In the second round of testing, similar areas for improvement were identified as in the first round of testing despite OTA having made changes to address these issues. Of most significance was the recommendation made after testing to improve the clarity of the message in the television commercial about the need to have a discussion with family members regarding organ and tissue donation.68 This was identified as an area for improvement in the first, second and fourth rounds of testing for the Phase 1 materials.69 OTA advised the ANAO that it considered the recommendations made as a result of testing and implemented those changes considered appropriate.

3.26 In respect to the Phase 2 materials, areas identified for improvement in testing had been addressed by the second round of Phase 2 testing. However, there was limited testing undertaken of the Phase 2 messaging—particularly in regional areas—to demonstrate that this would be an effective message.70 OTA advised the ANAO that the Phase 2 testing methodology was recommended by the research agency based on its available budget.

Review and approval by the Independent Communications Committee

3.27 Under the 2010 advertising guidelines, the role of the Independent Communications Committee (ICC)71 was to consider whether advertising campaigns valued at more than $250 000 complied with key aspects of the advertising guidelines, and provide advice to the relevant agency regarding compliance. In total, OTA met with the ICC eight times and submitted for consideration its advertising materials, Chief Executive certification72, compliance statement in relation to the advertising guidelines, testing results, and media plan.

3.28 The advertising guidelines also required that campaigns comply with relevant legislation and procurement rules.73 OTA reported a legislative breach to the ICC in its October 2009 ICC submission. OTA noted that there were breaches relating to the financial approval requirements established by the Financial Management and Accountability Regulations (1997) in relation to the appointment of public relations and research companies.74 OTA reported that it subsequently reviewed and improved internal business processes as a result of identifying these breaches.

Performance and outcome indicators for Phases 1 and 2

3.29 OTA identified a range of internal performance indicators for Phases 1 and 2 of the campaign:

- website statistics, online social media activity and online search engine key word hits;

- the number of enquiries from the general public to the DonateLife Network;

- news and editorial media coverage and post campaign analysis of media placements by the preferred Australian Government provider; and

- the number of new registrations on, or updates to, the AODR.

3.30 Phase 1 of the campaign also included a performance indicator relating to the number of families who initiate the discussion about donation in a hospital setting. OTA advised that this performance indicator was not used in Phase 2 as it would be difficult to directly attribute such an outcome to the advertising campaign.

3.31 OTA’s key internal outcome indicators for tracking the effectiveness of the campaign were the levels of:

- family discussion in the past 12 months;

- reporting the discussion as memorable;

- awareness of family members’ wishes; and

- knowledge of the role of family consent.

3.32 As discussed in paragraph 3.20, OTA engaged an external agency to undertake a benchmark survey and six waves of tracking research throughout the campaign.75 Table 3.3 summarises the results of the tracking research for OTA’s key outcome indicators.

Table 3.3: Tracking of OTA’s key outcome indicators

|

Indicator |

Benchmark (%) |

Wave 1 (%) |

Wave 2 (%) |

Wave 3 (%) |

Wave 4 (%) |

Wave 5 (%) |

Wave 6 (%) |

|

|

|

Phase 1 |

Phase 2 |

||||

|

Had a family discussion (in the past 12 months) |

48 |

59 |

58 |

53 |

57 |

60 |

58 |

|

Discussion was memorable |

n/a |

n/a |

83 |

81 |

82 |

81 |

81 |

|

Awareness of family members’ wishes |

51 |

60 |

57 |

54 |

55 |

57 |

56 |

|

Awareness that consent is required |

64 |

72 |

73 |

70 |

71 |

74 |

70 |

Source: OTA internal document.

Note: The Wave 6 tracking research also asked whether families had ever had a discussion regarding organ and tissue donation and reported a 77 per cent response rate. OTA commissioned a seventh wave of research which was carried out in 2013, after the advertising campaign had ended. The response rate for whether families had ever had a discussion about organ and tissue donation was 75 per cent. The research results for Wave 7 are reported in Table 3.6.

3.33 The research indicated that overall, the outcomes for Phase 1 of the campaign tracked above the three benchmark indicators adopted for the campaign, while in Phase 2, overall outcomes improved marginally against two indicators and remained stable against one. In summary, Phase 1 of the campaign (at a cost of $9.2 million) achieved improved outcomes against the campaign benchmarks, while Phase 2 (at a cost of $4.6 million) delivered a more marginal return on investment, serving largely to help maintain the outcomes of Phase 1.

3.34 Overall, between the benchmark and Wave 6 results, there was a 10 per cent increase in family discussions; a five per cent increase in the awareness of family members’ wishes; and a six per cent increase in the proportion of people who understood that family consent is required for donation to proceed.

3.35 The tracking research for Phase 1 noted that while there had been an increase in family discussion levels, males and people aged 18 to 29 years old and over 65 years old were less likely to have discussed their donation wishes. Consequently, in its evaluation of Phase 1, OTA identified people aged 18 to 29 years old, males and people aged over 65 years old as groups which required further attention. OTA advised the ANAO that it implemented a range of campaign initiatives targeted at young adults, including media strategies, videos, postcards and a Youth Support Kit. Notwithstanding these initiatives, the Wave 6 research results indicated that there was still potential to improve the knowledge and awareness of people aged 18 to 29 years old as they were the most likely to be influenced by the advertising campaign but the least likely to have seen the advertising.

3.36 There was a six per cent increase in awareness that consent is required between the benchmark and Wave 6 testing (to 70 per cent). However, awareness among people aged 18 to 29 years old in Wave 6 was lower than the general benchmark level of 56 per cent. Although this is a low rate of awareness for young people, it represented an improvement of three per cent against the benchmark level (53 per cent).

Objectives of the campaign

3.37 The three overarching objectives of the campaign were to:

- encourage Australians to discuss organ and tissue donation with their families and to understand the role of the family in providing consent for donation to proceed;

- increase the number of Australian families who know, accept and commit to uphold each other’s wishes; and

- increase the number of families who consent to and initiate organ and tissue donation requests.

3.38 Through the tracking research results, OTA monitored: discussion levels; awareness that family consent is required for donation to proceed; and the proportion of families who indicated that they knew their family members’ wishes (refer Table 3.3). In Wave 6 of the tracking research, participants were also asked whether they would uphold their family members’ wishes regarding donation, however, this question was not included in the earlier waves of research. Ninety-two per cent of the respondents indicated they would uphold their family members’ wishes.

3.39 During the course of the campaign, there was no information available on the level of family initiated discussion in hospital settings about organ and tissue donation as this information was only collected from 2013 using the DonateLife Audit tool.

3.40 Contributing to an increase in the family consent rate is an overall objective of the Community Awareness and Education Program.76 OTA advised that between 2010 and 2012, there was an increase of seven per cent in family consent rates from 54 per cent to 61 per cent. These results were below the target level of 75 per cent which has been in place since 2011–12.77

Evaluations of the campaign

3.41 Consistent with the 2010 advertising guidelines78, OTA undertook evaluations of each phase of the campaign including the extended phases. Timely and robust analysis of the progress of initiatives enables entities to identify and address potential issues with implementation and contributes to improvement processes.79 Evaluations should identify benefits realised as well as opportunities for improvement. Similarly, the 2010 advertising guidelines indicated that campaign evaluations should assess the effectiveness of government campaigns.

3.42 OTA’s evaluations assessed the effectiveness of media channels, as well as the advertisements. OTA also included two ‘lessons learned’ sections in its evaluations; one was focussed on the campaign activities and the second was focussed on the management of the campaign. OTA’s evaluations of Phase 1 and the extension of Phase 1 observed scope for improvement in respect to campaign activities and management, and identified initiatives which had worked well and should be repeated. While OTA’s evaluations for Phase 2 and the extension of Phase 2 identified initiatives which worked well, it did not identify any areas for improvement, notwithstanding the marginal improvement in outcomes reported for Phase 2 by the tracking research (refer to paragraph 3.33).

Post-campaign activities