Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Security Works at Parliament House

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The Department of Parliamentary Services (DPS) supports the work of the Australian Parliament, including providing security, facilities and maintenance for the Parliament House building.

- From 2014–15, DPS undertook a security upgrade capital works program to improve physical security at Parliament House.

Key facts

- In 2020-21, DPS had an annual operating budget of $271.6 million and 1,031 staff.

- In 2014, the National Terrorism Alert Level increased.

- In October 2014, DPS developed a security upgrade capital works program to improve physical security at Parliament House.

What did we find?

- The planning and delivery of the security upgrade capital works program at Parliament House by DPS was largely effective.

- Governance arrangements and planning for the program were largely effective. Program management would have been improved by documenting project management quality assurance processes.

- Procurement action complied with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, with gaps identified in the documentation of contractual management arrangements.

- DPS did not establish effective contract administrative and performance monitoring arrangements. An external assessment of the effectiveness of some components of the capital works program in reducing the physical security risks identified in 2014, commenced in December 2020.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made three recommendations to DPS related to the program.

- DPS agreed with two of the recommendations, and partly agreed to one recommendation.

$2.6bn

Value of the Parliament House building as at 30 June 2020.

4700

Number of rooms in the Parliament House building.

$145.4m

Comprising $126.7m capital funding and $18.7m expense funding for the security upgrade capital works program.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Department of Parliamentary Services (DPS) supports the work of the Australian Parliament, including providing facilities and maintenance for the Australian Parliament House (Parliament House) building. From 2014–15, DPS undertook a security upgrade capital works program (the program) to improve physical security at Parliament House. DPS procured six head contracts and 13 consultancies and other contracts to undertake the works.

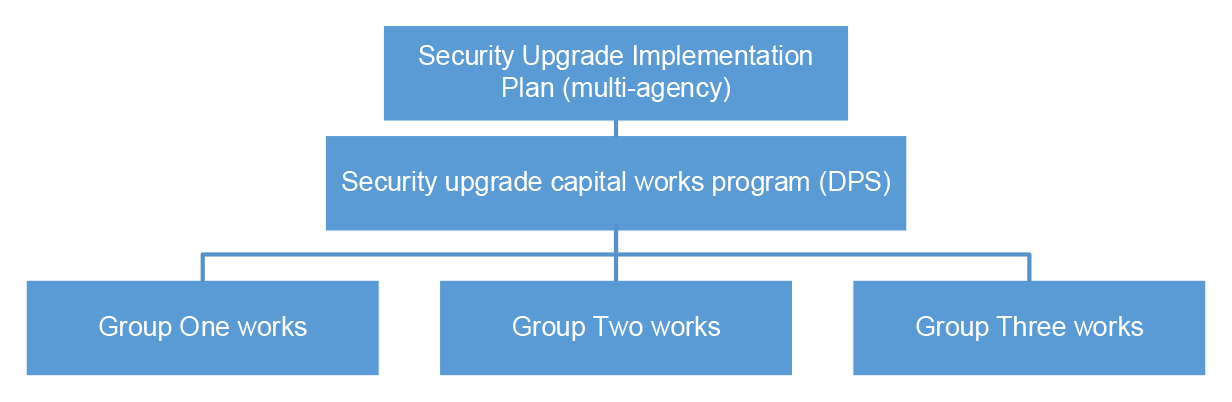

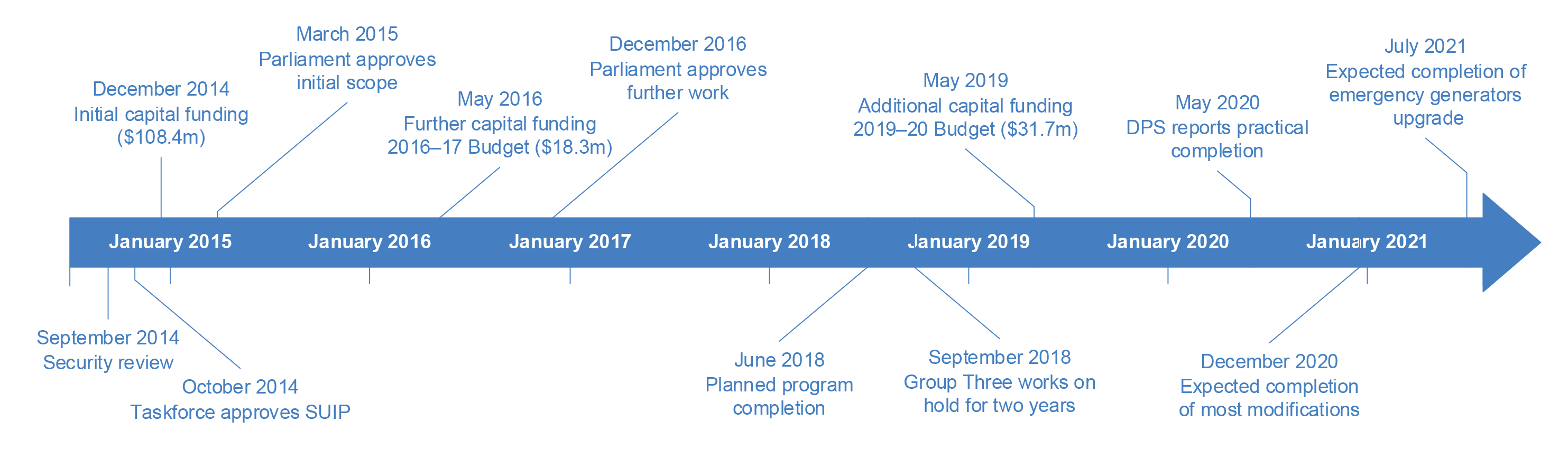

2. In the 2014–15 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, DPS was allocated $108.4 million capital funding and $18.7 million expense funding to undertake the program. The House of Representatives and the Senate approved the initial scope of works in March 2015.1 In April 2015 DPS was planning the program of works in three groups.2

- Group One — secure hardening of several entry points and identified areas of potential vulnerability.

- Group Two — major enhancements to security infrastructure, including the access control and closed-circuit television (CCTV) systems, and external glass facade.

- Group Three — further building infrastructure upgrades, subject to additional funding approvals.

3. In the 2016–17 Budget DPS was allocated a further $18.3 million in capital funding over two years for strengthening the main and side skylights. The House of Representatives and the Senate approved further perimeter security works on 1 December 2016. Additional capital funding of $31.7 million over four financial years (2018–19 to 2021–22) was provided in the 2019–20 Budget for DPS to replace the auxiliary power system (emergency generators), and to upgrade the mobile phone antenna. This funding was in addition to the appropriation in 2014–15 that included an emergency generator measure.

4. The program was budgeted to run until 30 June 2018, with a one-year rectification period. Group One works were completed in June 2016 and the defect liability periods ended in June 2017. DPS extended the expected completion timeframe for the remainder of program covering Group Two works by 12 months to 30 June 2019, and then in 2019 by a further six months to 31 December 2019. In September 2020, DPS reported that the Parliament House security upgrade project reached practical completion in May 20203, with minor additions and modifications still underway to fully realise the project’s objectives, and these were expected to be completed by December 2020.4

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. Two reports by the Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee in 2015 and two performance audits by the ANAO in 2015 and 2016 identified areas for improvement in DPS contract management. The delivery of the security upgrade capital works program was described by DPS as the largest capital works since the construction of Parliament House. This audit was included as a potential audit in the ANAO’s 2019–20 annual audit work program. On 14 November 2019, Senator Kimberley Kitching wrote to the Auditor-General raising specific concerns with the contract management of the program.5 Given the Parliamentary interest, this audit was undertaken to assess the effectiveness of the DPS planning and delivery of the security upgrade capital works program.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of planning and delivery of the security upgrade capital works program at Parliament House by DPS. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Did DPS effectively govern and plan the security works program?

- Did DPS effectively procure service providers to deliver the security works program?

- Did DPS effectively implement the security works program and control security risks?

7. The audit did not examine the Group Three auxiliary power system (emergency generators) project as works were underway, other capital works undertaken by DPS, building or asset maintenance, or other aspects of security at Parliament House — such as cyber security, or the operation of the Parliamentary Security Service.

Conclusion

8. The planning and delivery of the security upgrade capital works program at Parliament House by DPS was largely effective.

9. Governance arrangements and planning for the program were largely effective. DPS effectively contributed to the development of the program, and governance bodies largely fulfilled their roles and responsibilities. However, project management quality assurance processes were not fully implemented and there was no program performance framework.

10. DPS was largely effective in procuring suppliers to deliver the program. Procurement action complied with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules. Contract formation was consistent with Commonwealth standards, although with potential risks in the areas of timely execution, and there were gaps in the documentation of contractual management arrangements.

11. Implementation of Group One and Group Two of the program was partly effective. DPS conducted communications activities according to plan, and reporting was largely effective, but with gaps in oversight at critical periods. DPS management and oversight of contract performance was partly effective, as DPS did not establish effective administrative and performance monitoring arrangements. An external assessment of the effectiveness of some components of the capital works program in reducing the physical security risks identified in 2014, commenced in December 2020.

Supporting findings

Governance and planning

12. DPS made a largely effective contribution to the development of the program through its membership of the Parliament House Security Taskforce and work to validate project delivery times and costs. DPS clearly set out program objectives and costs in the funding proposal to government. All funding was allocated upfront in 2014–15, and there was evidence that the program would be delivered over a number of years that was yet to be determined.

13. DPS’ governance of the program was largely effective. The Project Control Group operated as DPS’ primary governance body. DPS had established quality control frameworks, but did not fully implement the planned processes.

14. The approach to planning for the program was partially effective. The absence of program performance framework and an approach to track program delivery timeframes in a consistent and coordinated way, resulted in a limited clear line of sight between agreed delivery timeframes from the Australian Parliament House Security Upgrade—Implementation Plan (SUIP) and later revised timeframes from the contracts.

Procurement

15. DPS complied with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules for the head contract procurements examined by the ANAO. Procurement processes were guided by procurement strategies, approaches to market met requirements, and open tenders were evaluated in accordance with tender evaluation plans to ensure value for money.

16. DPS established effective contracts with suppliers, using Australian Government templates for all six head contracts and 12 of 13 consultancies and other contracts examined. Records management and timely execution of contracts were areas for improvement. Contract management plans were in place for three head contracts, although DPS did not have contract management and associated plans for all head contracts, as recommended by internal policy.

Implementation

17. Communications and reporting were largely effective. DPS developed communication plans that sought to raise awareness amongst building occupants. DPS maintained oversight of communications throughout the program, but did not measure or review the effectiveness of communication activities. DPS planned, undertook and reviewed internal reporting.

18. DPS’ management and oversight of contract performance was partly effective. DPS did not establish key administrative arrangements to support contract management, including conflicts of interest and contract management plans. DPS established largely effective performance monitoring arrangements for the contracts. DPS monitored delivery in terms of budget and time; however, it was not evident that DPS had sufficient oversight over scope changes. Assessment of a contract that ended in December 2019 remained outstanding.

19. While accreditation of security zones provided assurance over elements of the capital works, an external security assessment of the capital works program would provide additional assurance that the program effectively controlled the five physical security risks identified in 2014. DPS assessed the intended effectiveness of some risk controls before implementation, but did not assess the effectiveness of all controls once implemented.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.26

The Department of Parliamentary Services:

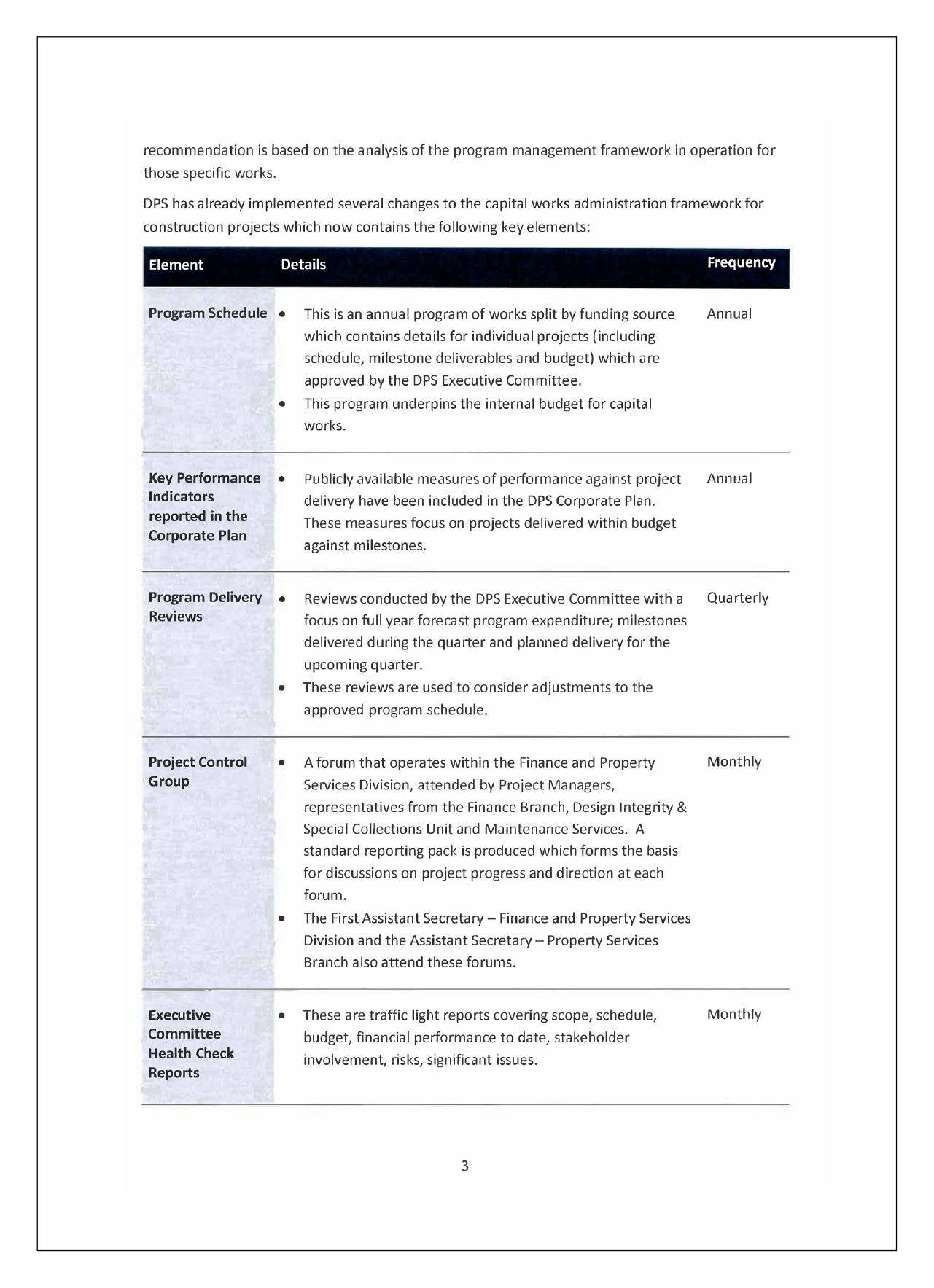

- reviews the adequacy of the program management framework, policies and procedures that it has in place to administer a capital works program; and

- ensures that it has quality assurance arrangements in place to assess whether the program management framework, policies and procedures are used effectively.

Department of Parliamentary Services response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 4.52

The Department of Parliamentary Services undertake closure tasks for all contracts in accordance with internal policy.

Department of Parliamentary Services response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 4.72

The Department of Parliamentary Services finalise the external security reviews of the capital works program, and make recommendations to the Security Management Board and Presiding Officers on any subsequent action identified by the these reviews.

Department of Parliamentary Services response: Partly Agreed.

Department of Parliamentary Services summary response

DPS welcomed the audit of the security upgrade works and agrees with the recommendations in principle. DPS has simultaneously used this audit process as an opportunity to conduct a post-implementation review and further develop program management processes as part of its continuous improvement initiatives.

DPS disagrees with a number of residual statements and findings in this report which could have been resolved before the reporting deadline with more transparent lines of enquiry. During the audit, DPS provided well in excess of 12,000 documents to support ANAO requests. This included contextual information to assist the audit team to understand the program framework. Unfortunately, limited discussion and context for lines of enquiry resulted in inaccurate draft findings and considerable follow up work by DPS which continued until the production of the section 19 report. DPS acknowledges that the ANAO has incorporated most of our responses and would welcome greater dialogue to enable a more effective review process.

DPS disagrees with the ANAO’s assessment that there was no program performance framework in place and that the KPl’s from the Security Upgrade Implementation Plan (SUIP) were not central to reporting on the progress of works being managed through that framework. The ANAO was unable to articulate what an effective program performance framework comprises and where this diverges from the approach taken by DPS in: managing the development of the detailed scope of works (as agreed by the Presiding Officers and the Parliament consistent with the SUIP); the progress of the implementation of those works (including managing contractor performance); and the review of the effectiveness of those works in addressing the security risks treated through the SUIP.

Project delays were experienced with some of the works program but DPS questions the value of measuring delays using high-level indicative delivery dates identified very early in the SUIP. These dates, which can only be viewed as estimates, preceded the complex detailed design and planning work for change to a monumental and architecturally significant building with nationally important heritage values. The design process alone required modelling of options before suitable solutions were adopted to minimise impact on the and Architect’s design intent. The resulting disruptive construction activity was also necessarily scheduled around parliamentary sitting periods and other significant events, generating intrinsic and sometimes unpredictable delays.

ANAO comment

20. The DPS Security Works Program performance framework is discussed at paragraph 2.35 and Appendix 5. DPS oversight of scope changes is detailed at paragraphs 4.33, 4.34, and 4.37 to 4.39. DPS performance monitoring of contract scope, time and budget is set out at paragraphs 4.25 to 4.48. An external security assessment of the capital works to provide assurance that the program effectively controlled the five physical security risks identified in 2014, is discussed at paragraphs 4.67 to 4.74.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Records management

Contract management

Governance and risk management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Department of Parliamentary Services (DPS) supports the work of the Australian Parliament, including providing facilities and maintenance for the Australian Parliament House (Parliament House) building. From 2014–15, DPS undertook a security upgrade capital works program (the program) to improve physical security at Parliament House. DPS procured six head contracts and 13 consultancies and other contracts to undertake the works.

Security Works at Parliament House

The Department of Parliamentary Services

1.2 The Parliamentary Service Act 1999 establishes DPS as one of four parliamentary departments, and DPS staff are employed under that Act.6 The DPS Secretary reports to the Presiding Officers of the Parliament — the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives. As a non-corporate Commonwealth entity, the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and related policies apply to DPS.

Providing facilities and maintenance for the Parliament House building

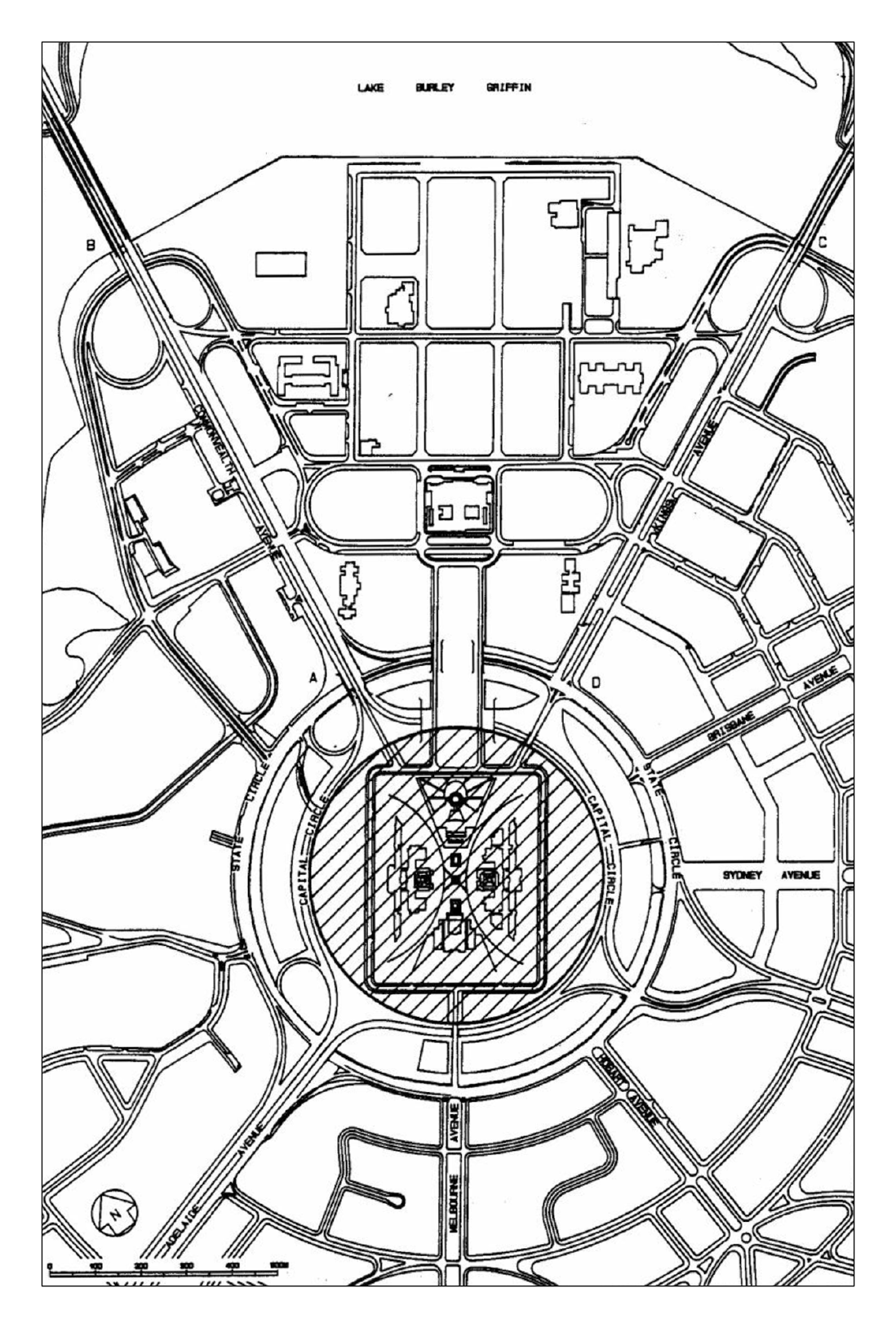

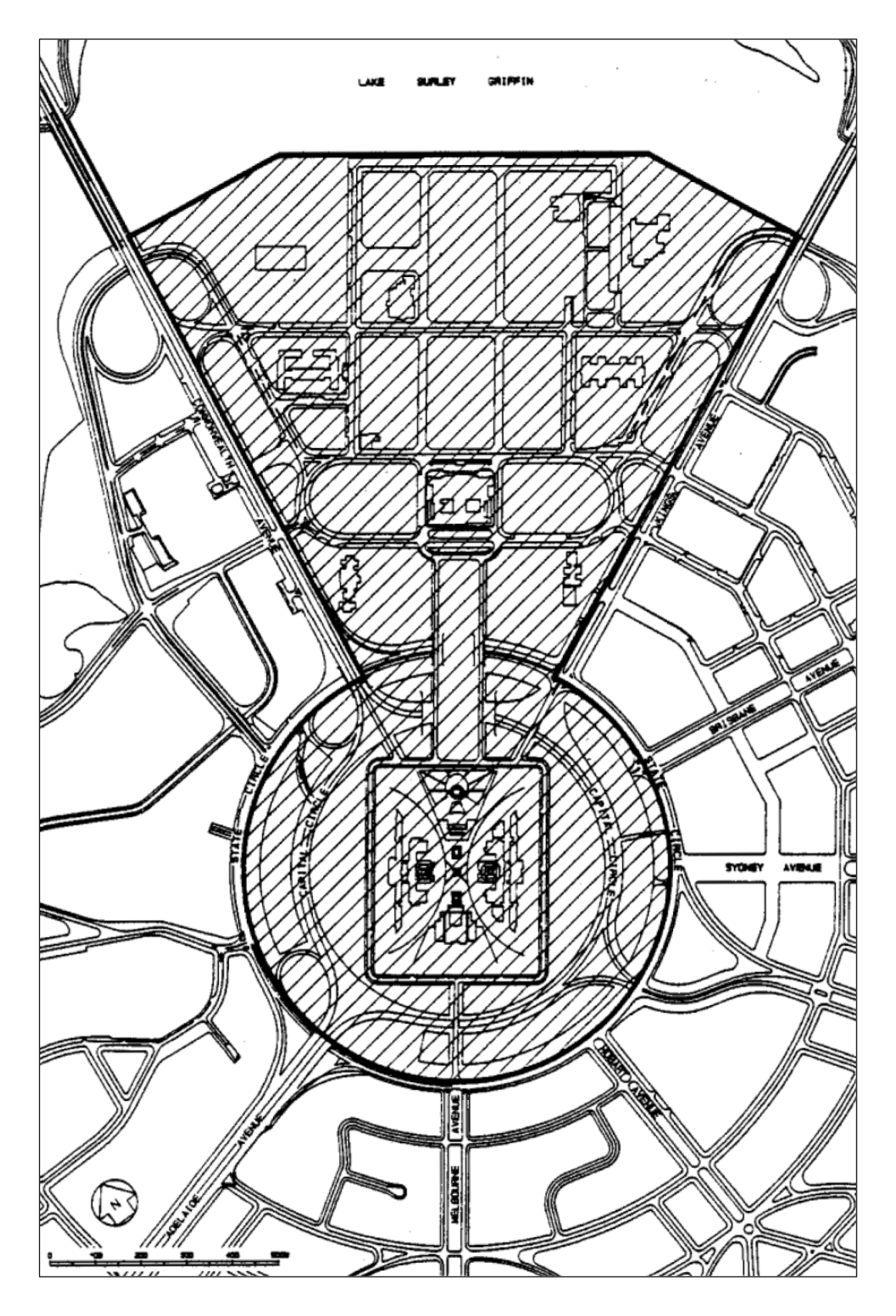

1.3 The Parliamentary precinct occupies a 35-hectare site, comprising approximately 4700 rooms across four levels, with a total floor area of more than 267,000 square metres (see Appendix 2).7 The protection of Parliament House against the risk of physical attack is critical to ensuring continuity, and public confidence, in the proper functioning of the Australian Parliament. Considering the multiple users of the building includes parliamentarians, building occupants and visitors, DPS’ effective stewardship of Parliament House involves ensuring a secure environment while maintaining public accessibility.

1.4 Parliament House received 746,844 visitors over the 2018–19 period, operating under arrangements where the building is accessible every day of the year inclusive of weekends and public holidays, with the exception of Christmas day.8 In September 2020 DPS reported that it did not meet the 2019–20 number of visitors target, due to bushfires throughout Australia in late 2019, and the impacts of COVID-19 which resulted in the building being closed to the general public from 26 March 2020 until 4 July 2020.9 Visitor numbers and occupancy limits have continued to be restricted in response to public health authority advice and ACT Government requirements.

1.5 The Presiding Officers have specific roles in relation to building works within the Parliamentary zone (see Appendix 2). The National Capital Authority is the relevant planning authority for Commonwealth buildings within the National Triangle. The Presiding Officers are responsible for security arrangements at Parliament House, with specific roles under the Parliamentary Precincts Act 1988 and the Parliamentary Service Act 1999.10

Security upgrade capital works program

1.6 Following an increase in the National Terrorism Alert Level in September 2014, the Presiding Officers accepted the recommendations of a series of reviews of security arrangements at Parliament House11 and established a multi-agency Parliament House Security Taskforce (the Taskforce)12 to oversee implementation of agreed measures.13

1.7 In October 2014, the Taskforce developed the Australian Parliament House Security Upgrade—Implementation Plan (SUIP), which assigned specific tasks to individual agencies. DPS was assigned responsibility for undertaking a security upgrade capital works program to improve physical security (Figure 1.1), alongside other measures related to the provision of security operations at Parliament House and updates to the security policy and governance framework.14 The program aimed to reduce five physical security risks assessed as ‘high’, although no target was set for the reduction in risk.

Figure 1.1: The SUIP and the capital works program

Source: ANAO, based on DPS documents.

1.8 In the 2014–15 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, DPS was allocated $108.4 million in capital funding and $18.7 million expense funding to undertake the program.15 The House of Representatives and the Senate approved16 the initial scope of works for proposed perimeter security enhancements in March 2015, comprising:

- a perimeter fence at the southern facade of the Ministerial wing;

- a gate house facility outside the entrance to the Ministerial wing;

- vehicle bollards at the base of the Ministerial entrance stairs; and

- glazing replacement at Ministerial ground floor entrance.17

1.9 In April 2015 DPS was planning the program of works in three groups.18

- Group One — Secure hardening of several entry points and identified areas of potential vulnerability (the perimeter security enhancements approved in March 2015 formed the package of work in Group One).

- Group Two — Major enhancements to security infrastructure, including the access control and CCTV systems, and external glass facade.

- Group Three — Further building infrastructure upgrades, subject to additional funding approvals.

1.10 In the 2016–17 Budget, DPS was allocated $18.3 million in further capital funding over two years for strengthening the main and side skylights19, and these works were assigned to Group Two. The House of Representatives and the Senate approved further perimeter enhancements security works on 1 December 2016, comprising:

- fencing to the northern and southern grass ramps;

- forecourt fencing along the angled wall;

- Ministerial wing fencing along the angled wall;

- barriers on the eastern and western building perimeter;

- camera surveillance (CCTV systems); and

- selected glazing replacement around the building perimeter.20

1.11 A June 2015 project management plan outlined that the Group 3 works related exclusively to Ministerial wing works that were not funded. In February 2016, a project report detailed that the Ministerial wing works were no longer required. In June 2016, DPS had assigned a single project to Group Three works that had received funding in the 2014–15 capital works program appropriation relating to the upgrade of emergency generators. An August 2016 project management plan (that was updated in August 2018), provided a work breakdown for the three groups of works (see Appendix 3).

1.12 DPS advised its Audit Committee in September 2018 that in conjunction with the Presiding Officers an agreement had been made to place Group Three works on hold for two years. Additional capital funding of $31.7 million over four financial years (2018–19 to 2021–22) was provided following the 2019–20 Budget measure for DPS to replace the auxiliary power system (emergency generators), and to upgrade the mobile phone antenna.21 A DPS project progress report in December 2019 detailed that the auxiliary power system project completion date was July 2021.

Delivery of the capital works program

1.13 The program commenced in 2014–15 and was budgeted to run until 30 June 2018, with a one-year rectification period.22 Group One works were completed in June 2016 and the defects liability period ended in June 2017. DPS extended the expected completion timeframe for the remainder of the program covering Group Two works by 12 months to 30 June 201923, and then in 2019 by a further six months to 31 December 201924 (Figure 1.2).

1.14 In September 2020, DPS reported that the Parliament House security upgrade project reached practical completion in May 202025, with minor additions and modifications still underway to fully realise the project’s objectives. These were expected to be completed by December 2020.26

Figure 1.2: Timeline of the security upgrade capital works program

Source: ANAO, based on DPS documents.

Previous reviews and audits

1.15 The Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee has conducted three inquiries relevant to the program. The inquiry reports:

- tabled on 25 June 2015 — on the proposed security upgrade capital works27;

- tabled on 17 September 2015 — on DPS, including contract management28; and

- is expected to table on 30 June 2021 — on the operation and management of DPS.

1.16 The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has undertaken two performance audits of DPS contract management in areas separate from the program29:

- Auditor-General Report No. 24 2014–15, Managing Assets and Contracts at Parliament House, identified deficiencies in DPS contract management; and

- Auditor-General Report No. 19 2016–17, Managing Contracts at Parliament House, found there had been an overall improvement in the establishment and management of contracts, but there was a need to improve contract management planning, risk management planning, and monitoring of contractor performance.

1.17 DPS undertook eight internal audits relevant to the program between 2015 and 2020.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.18 Two reports by the Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee in 2015 and two performance audits by the ANAO in 2015 and 2016 identified potential improvements to DPS contract management. The delivery of the security upgrade capital works program was described by DPS as the largest capital works since the construction of Parliament House. This audit was included as a potential audit in the ANAO’s 2019–20 Annual Audit Work Program. On 14 November 2019, Senator Kimberley Kitching wrote to the Auditor-General raising specific concerns with the contract management of the program.30 Given the Parliamentary interest, this audit was undertaken to assess the effectiveness of DPS’ planning and delivery of the security upgrade capital works program.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.19 The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of planning and delivery of the security upgrade capital works program at Parliament House by DPS. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Did DPS effectively govern and plan the security works program?

- Did DPS effectively procure service providers to deliver the security works program?

- Did DPS effectively implement the security works program and control security risks?

1.20 The audit did not examine the Group Three auxiliary power system (emergency generators) project as works were underway and other capital works undertaken by DPS, building or asset maintenance, or other aspects of security at Parliament House such as cyber security or the operation of the Parliamentary Security Service.

Audit methodology

1.21 Audit procedures included:

- reviewing DPS documents; and

- interviewing key management personnel at DPS and relevant staff from the project manager/contract administrator.

1.22 The ANAO received four citizen contributions.

1.23 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $480,000.

1.24 Team members for this audit were Nathan Callaway, Barbara Das and Peta Martyn.

2. Governance and planning

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Parliamentary Services (DPS) effectively governed and planned the security upgrade capital works program (the program).

Conclusion

Governance arrangements and planning for the program were largely effective. DPS effectively contributed to the development of the program, and governance bodies largely fulfilled their roles and responsibilities. However, project management quality assurance processes were not fully implemented and there was no program performance framework.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at improving DPS’ program management framework.

2.1 The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s Guide to Implementation Planning stated that ‘effective governance arrangements are critical to successful delivery’ and that planning should provide ‘a structured approach or path for how an initiative will be implemented’.31 The ANAO examined whether DPS:

- effectively contributed to the development of the program;

- established effective governance arrangements to oversee the program; and

- used an effective planning process for the program.

Did DPS effectively contribute to the development of the program?

DPS made a largely effective contribution to the development of the program through its membership of the Parliament House Security Taskforce and work to validate project delivery times and costs. DPS clearly set out program objectives and costs in the funding proposal to government. All funding was allocated upfront in 2014–15, and there was evidence that the program would be delivered over a number of years that was yet to be determined.

2.2 For initiatives that involve multiple entities, it is important to clearly identify which entities are responsible for the various aspects of the initiative.32 The ANAO examined whether DPS effectively contributed to the development of the Australian Parliament House (Parliament House) Security Upgrade Implementation Plan (SUIP) and the proposal seeking funding for the plan.

2.3 In 2014 following the heightened threat environment in Australia33, there was an urgency to address the security risks related to Parliament House identified in the 2014 reviews (see paragraph 1.6). The timeline for the development of the program is detailed in Box 1.

|

Box 1: Key milestones relating to the development of the program |

|

The Presiding Officers, at the request of the Prime Minister, established the Parliament House Security Taskforce on 22 September 2014. The Presiding Officers endorsed the SUIP on 22 October 2014. DPS submitted the funding proposal in November 2014 for the security works and funding was approved on 15 December 2014. |

Australian Parliament House Security Upgrade Implementation Plan

2.4 The Parliament House Security Taskforce (the Taskforce) developed the program and created an implementation plan, with DPS and other entities providing input.34 The Secretary of DPS was a member of the Taskforce, which first met on 22 September 2014. DPS contributed to the development of the program by responding to requests from the Taskforce, providing advice about moral rights consultation and circulating the results of related audits and trials.

2.5 The SUIP, approved in October 2014, set out four staged categories of work for implementation, with some works planned to occur sequentially. At this time the planned completion date for the program was 31 December 2016. In May 2015 DPS developed the Security Upgrade Transition Plan and revised the SUIP, with a new grouping and schedule of the works into three groups, with a revised completion date of July 2017 for the program. DPS advice to the Taskforce when submitting the revised SUIP was that the transition plan packaged works into groups with the aim of delivering the various works in the most efficient manner and involved some reprogramming of works. The Taskforce endorsed the transition plan, including the revised timeframes, at its May 2015 meeting.

Funding proposal

2.6 The funding proposal was to implement the physical enhancements outlined in the SUIP to address the security risks related to Parliament House, and clearly outlined program objectives and costs. DPS stated that each of the proposed actions would provide a risk treatment or threat mitigation that, when considered holistically, would provide a significantly improved level of security for the Parliament and its occupants. DPS requested that all capital funding be appropriated up-front in the first financial year in 2014–15. In May 2015, approval was sought for the money to be rolled over and re-phased for forward financial years. The funding proposal did not specify timeframes for the delivery of the security works, and recognised that whilst the capital costs could be committed, the actual construction, commissioning and defect liability period would extend into the out years. As part of the funding process, DPS identified pressures and constraints related to timing. In particular, the delivery schedule was based on limited information and DPS considered there was a risk that not all factors had been considered that could impact on the delivery of the works.

Did DPS establish effective governance for the program?

DPS’ governance of the program was largely effective. The Project Control Group operated as DPS’ primary governance body. DPS established quality control frameworks, but did not fully implement the planned processes.

Governance framework

2.7 The Guide to Implementation Planning outlined that:

- governance arrangements should be documented to show the lines of decision-making responsibility, consultation channels and avenues for horizontal collaboration; and

- the roles and responsibilities of each person or group involved in the initiative needs to be clearly defined, agreed and documented.35

Oversight

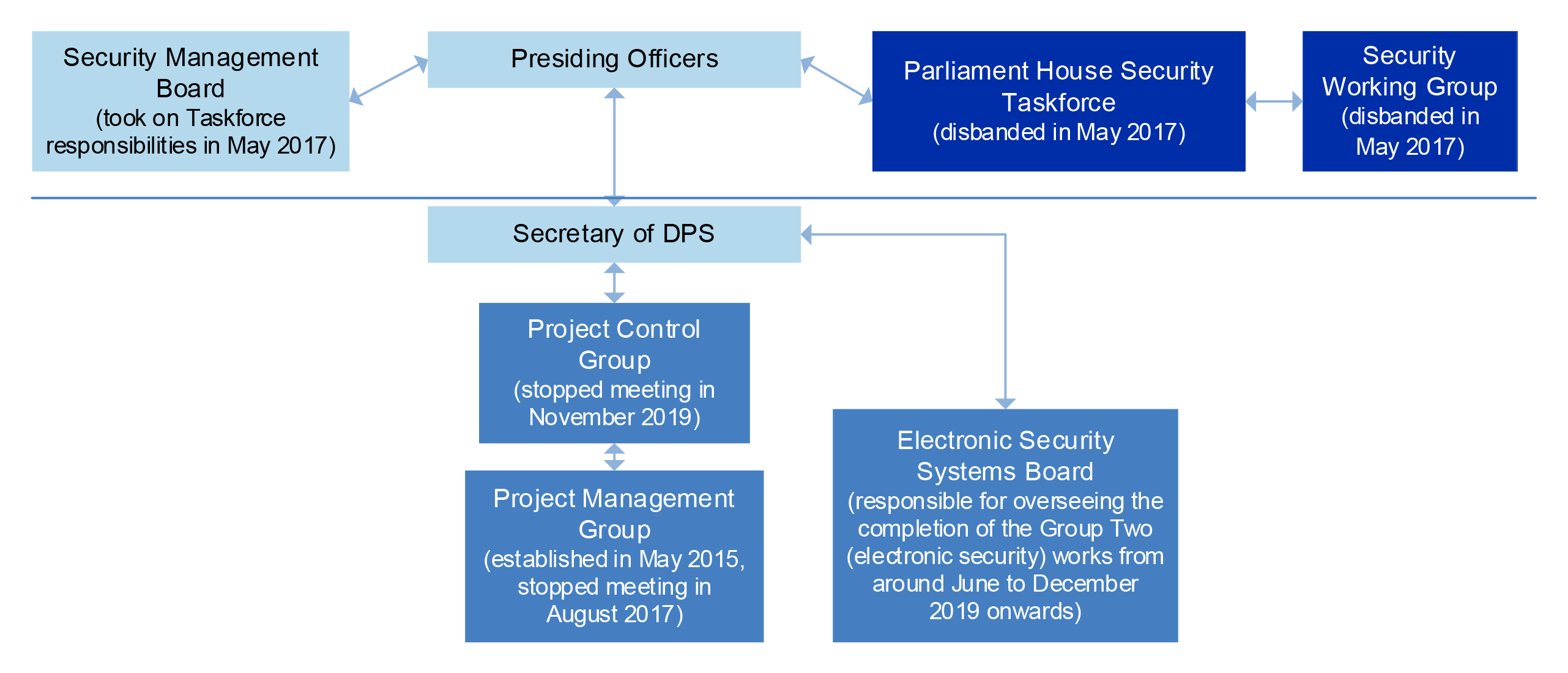

2.8 The Secretary of DPS approved a governance framework in December 2014 for DPS’ implementation of the program. The key oversight arrangements are illustrated at Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Governance arrangements for the security works upgrade program

Legend:

indicates external governance arrangements for the program.

indicates internal governance arrangements established for the program.

indicates governance arrangements that were in existence before the program commenced.

Notes: The Security Management Board membership includes: the Secretary of DPS (or appointee); an SES employee of the Department of the Senate; an SES employee of the Department of the House of Representatives; and the Australian Federal Police Commissioner or Deputy Commissioner.

The Parliament House Security Taskforce (the Taskforce) membership included: the Speaker of the House of Representatives (Chair); the President of the Senate; an Associate Secretary (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet); two Assistant Commissioners (Australian Federal Police); a Deputy Secretary (Attorney-General’s Department); a representative (Australian Security Intelligence Organisation); a Deputy Secretary (Department of Finance); and the Secretary, DPS. In May 2017, the Taskforce’s responsibilities were transferred to Security Management Board.

The Project Control Group membership included the following DPS staff: the First Assistant Secretary, Building and Asset Management Division (Chair); the Chief Operating Officer; the Chief Information Officer; the Assistant Secretary, Program Delivery; the Assistant Secretary, Asset Development & Maintenance; the Assistant Secretary, Security; the Assistant Secretary, Parliamentary Experience; the Assistant Secretary, Strategic Asset Planning & Performance; the Chief Financial Offer; and the Parliamentary Librarian.

The Project Management Group Membership included the following DPS staff: Assistant Secretary Program Delivery Branch (Chair); Assistant Secretary, Security Branch; Assistant Secretary, Asset Development & Maintenance Branch; Assistant Secretary, ICT Strategy Planning and Applications; Assistant Secretary, ICT Infrastructure; the Project Director; and the Assistant Project Director.

Source: ANAO depiction of key program governance arrangements.

2.9 There were four different versions of the governance structure diagrams in DPS documentation in the 2014–15 period.36 DPS advised that the different versions of the diagrams reflected updates resulting from embedding the program over time. Later changes to the governance structure were not updated to reflect the: closure of the Program Management Group in August 2017; Taskforce responsibilities being transferred to the SMB in May 2017; and introduction of the specific governance arrangements in June 2019 for the Electronic Security Systems Board that had some responsibilities relating to the delivery of the Group Two (electronic security) works contract.

2.10 The Presiding Officers were involved in providing advice, direction and approval for the program, and from September 2017 received capital works digest reports from DPS.

2.11 The key DPS internal oversight arrangements operated as follows.

- The Secretary of DPS37 established the Project Control Group (PCG) as DPS’ primary governance body. The PCG reported to the Secretary of DPS, and provided advice and guidance around planning and implementation; overseeing communication and consultation approaches; and monitoring the delivery of the program. Minutes documented the PCG meetings from January 2015 until the final meeting in November 2019. Commencing from the period around June to December 2019, the Electronic Security Systems Board had responsibility for overseeing the completion of the Group Two (electronic security) works.

- For the Group Two works, DPS established the Project Management Group (also known as the Program Board) in May 2015 to support the Project Control Group (PCG). The Project Management Group was introduced to assist with communications, stakeholder engagement and the resolution of operational issues as a prior step to the PCG. The Project Management Group met 18 times between May 2015 and August 2017, and their discussions were operational in nature, in accordance with their remit. DPS advised that a verbal direction was given by a DPS official that meetings were no longer to be held.

Roles and responsibilities

2.12 The Presiding Officers were the key approvers of the designs and decisions to progress the individual projects.38 The Secretary of DPS is accountable to and reports to both Houses of Parliament through the Presiding Officers. The PCG and Program Management Group were not decision-making bodies, although their membership included DPS senior executives who were decision makers within the department.

2.13 Having a single senior responsible officer for the delivery of large programs is considered good practice.39 DPS established the role of program sponsor. However, DPS documentation did not clearly demonstrate that this role was the senior responsible officer. DPS advised that there were four different program sponsors and five project directors over the life of the program.

2.14 The roles and responsibilities of other key program personnel — the project director and the project manager — were clearly defined. The roles and responsibilities of these positions were outlined in governance documentation and the program management plans.

- The project director was the management focal point between the senior executive, construction partners and internal stakeholders during the design and construction activities and was responsible for ensuring the early escalation of potential delays or resolving issues escalated through the various project work streams.

- The project manager was responsible for the management of the work streams within the program and the implementation of the works streams from initiation to handover and support.

2.15 The Guide to Implementation Planning also stated that ‘teams with appropriate capabilities and skills will need to be assembled’.40 In November 2014, DPS established the Program Delivery Branch, as a temporary unit, to plan and deliver all components of the program.41 The branch was established in recognition that ‘the extent of works required under the program was not able to be met using the existing DPS Project team staffing levels’.42 DPS intended that the branch would consist of a team within DPS supported by a contracted project delivery team. The branch had difficulties in attracting and retaining staff because of the lack of longer term job security and competing work priorities.43

2.16 In April 2015, DPS procured a project manager and contract administrator (PMCA). The PMCA was responsible for a substantial part of the general project management and contract administration for the program, including: developing and refining the scope, cost and program of work; undertaking procurements; contract administration; and program reporting. The PMCA team was an embedded part of the Program Delivery Branch.

2.17 In July 2017, the Program Delivery Branch merged with the Capital Works Branch44 with the aim of a more unified delivery of the capital works plan and the program, and to help minimise disruption to building occupants and visitors.

Program management and quality frameworks

2.18 A program management framework consists of the policies, procedures and tools used to support the management of a program, and ‘while program management is underpinned by project management skills, [program management] is a more complex and demanding discipline’.45

2.19 By March 2015, DPS had identified that:

- a multi-faceted project of this size and scale had not been undertaken at Parliament House since the building was originally constructed in the early 1980s;

- DPS had a poor record in delivering small to medium sized building construction and security projects, and although significant steps had been taken to improve this capability, the change process was still in its infancy; and

- DPS had a historically poor approach to engagement with the Heritage, Security and Visitor Experience areas when undertaking construction projects.

2.20 To address issues of project management, DPS adopted a new project methodology to be more flexible and responsive in delivering the program.46 DPS used program management plans covering: scope; quality; risk management; communication and stakeholder engagement; human resources; budget management; scheduling; governance and reporting; and procurement.

2.21 The ANAO ide ntified that at the outset of the program, there were gaps in policies or guidance in place relating to: the identification, selection and prioritisation of projects; program and project planning; design and approval of projects; and heritage assessment. In 2018–19, DPS implemented the Management of Design Integrity Framework (comprising consultation framework, policy and process documents), which was intended to ensure effective project management in partnership with designers and in consultation with moral rights administrators.47

2.22 DPS developed two quality frameworks for the program. The first quality framework was developed in June 2015, but was not approved by the delegate. The PMCA developed the second framework in August 2016. The quality frameworks aimed to:

- ensure that all project management processes are conducted in a quality manner (quality assurance) and that quality criteria for the outputs themselves (quality control) were developed — first quality framework; and

- increase certainty, and reduce the risk of project failure — second quality framework.

2.23 The first quality framework did not specify how quality assurance would be achieved, as defined — that is, ensuring that all project management processes were conducted in a timely manner, such as those included in the program management plan and outlined at paragraph 2.22. The framework stated that quality project management processes would be defined that applied to each project; however, it was not evident from documentation how this element of the quality framework was planned to operate and how it operated in practice. DPS advised in June 2021 that ‘DPS had ongoing day-to-day interactions with [the PMCA] to ensure that the processes in place are occurring and effective, which is a key element of DPS’ quality assurance that project management processes were undertaken in a quality manner’.

2.24 The second framework specified two aspects of quality:

- corporate quality accreditation, such as adherence to the National Code of Practice for the Building and Construction Industry; and

- project technical accreditation, which are project specific accreditations required to fulfil the project objectives and critical success factors.

2.25 DPS did not record key documents related to its quality control activities as required under its second quality framework: a quality assurance schedule to outline the project technical accreditation requirements, as well as an approved schedule of inspections, audits and reviews to ensure the quality of the program; and a quality assurance register to keep track of and record accreditation activities relating to the quality assurance of the program. In addition, DPS conducted three internal audits of the program and monthly reports addressed some compliance obligations relating to Commonwealth requirements around: heritage; work health and safety; and the Building Code 2013.

Recommendation no.1

2.26 The Department of Parliamentary Services:

- reviews the adequacy of the program management framework, policies and procedures that it has in place to administer a capital works program; and

- ensures that it has quality assurance arrangements in place to assess whether the program management framework, policies and procedures are used effectively.

Department of Parliamentary response: Agreed.

2.27 DPS has used this audit as an opportunity to conduct a post-implementation review and further develop program management processes as part of a program of continuous improvement. Elements of the program management framework currently in operation have been described in Appendix 1 - Entity Response.

Risk management framework

2.28 An appropriate risk management framework allows entities to effectively assess, control and monitor risks in order to achieve their business objectives. The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) prescribes that all Commonwealth entities must establish and maintain an appropriate system of risk oversight and management. The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy also provides guidance to Commonwealth entities on implementing these systems, including for establishing a risk management framework.

2.29 DPS established two risk management frameworks for the program.48 The two frameworks both addressed: risk governance arrangements; assessment processes; mitigation and treatment processes; and monitoring arrangements for the program. The first risk management framework, in place until August 2016, was not appropriate for the program as the risk management processes were not clearly set out and monitoring arrangements were not adequate. The second risk management framework was largely appropriate, and set out risk management processes, oversight arrangements and monitoring and review arrangements. A full assessment of DPS’ risk management framework for the program against the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy is at Appendix 4.

Did DPS use an effective planning process for the program?

The approach to planning for the program was partially effective. The absence of program performance framework and an approach to track program delivery timeframes in a consistent and coordinated way, resulted in a limited clear line of sight between agreed delivery timeframes from the SUIP and later revised timeframes from the contracts.

2.30 A planning process should provide a structured approach for how an initiative will be implemented to reach an outcome.49 Planning was undertaken at the program level through the development of program management plans (PMPs) and at the project level through the design phase.

Program planning

2.31 In November 2014, as part of the funding proposal, DPS noted that some of the security works which involved replacement or enhancement of obsolete equipment could be implemented immediately after receiving funding. Other measures that were more complex in nature, because they involved significant design changes or had implications for the design integrity of Parliament, would require dedicated project management and architectural resources to ensure that projects were delivered as quickly as possible.

2.32 DPS developed PMPs to operationalise the project management methodology. The PMPs were key program documents that were designed to be updated throughout the program and consisted of a collection of strategies and associated plans. The PMPs outlined arrangements for the program such as governance arrangements, stakeholders and roles and responsibilities. The most recent PMP dated August 2016 included ten associated plans covering management of: scope; risk; communications; human resources; procurement; quality; time; cost; workplace health and safety; and environmental.

2.33 Program planning was undertaken by DPS for the Group One and Group Two works. DPS provided the ANAO with four different PMPs for the program. As the planning process was ongoing and subject to review and updates, some of these plans had multiple versions.50

- The first plan was approved by the Secretary of DPS in December 2014. The plan focussed on establishing governance arrangements for the program, noting that other areas of the plan were still being developed such as: a risk management framework; an approach to quality; and a delivery schedule.

- The second plan was approved by the relevant First Assistant Secretary in May 2015. The plan provided greater details in the sub-plans and covered the Group Two works only.

- The third plan is dated June 2015; however, it is not evident who approved this plan and it does not have a finalised date. The plan covers similar areas to the May 2015 plan, however, it is unclear if this plan just related to Group One works.

- The fourth plan is dated August 2016 and it is not evident who approved the plan. This plan applied to the entire program, covering the areas identified in the paragraph above.

2.34 The May 2015 PMP/SUIP (see paragraph 2.5) grouped and scheduled works into three groups: Group One; Group Two; and Group Three (see Appendix 3). The first two groups contained 37 security works: 19 works for Group One works; and 18 for Group Two (10 physical security, one radio upgrade51 and seven electronic security). The Group Three works evolved over the life of the program, as outlined in paragraphs 1.11 and 1.12. As at March 2021, one project was still being delivered under Group Three that had received funding in the 2014–15 capital works program appropriation, relating to the upgrade of emergency generators. DPS procured six head contracts and 13 consultancies and other contracts to undertake Group One and Group Two works.

2.35 Appendix 5 sets out the ANAO’s assessment of DPS planning for the program. Program objectives were clearly outlined and costs were managed through cost management plans. DPS also engaged with stakeholders for the planning phase. However, planning did not establish an approach to track delivery timeframes in a consistent and coordinated way, such that there was a clear line of sight between agreed delivery timeframes from the SUIP and later revised timeframes from the contracts. At the outset of the program, six key performance indicators (KPIs) were set out in the SUIP covering: timeliness; cost; delivery of the works; mitigation of vulnerabilities; management of risks; and a review of the new measures. The KPIs were not incorporated into DPS’ PMPs and DPS did not monitor and report against the KPIs, and did not establish a program performance framework. DPS also did not review the third PMP in accordance with its review schedule and did not maintain adequate records of PMPs.

Design

2.36 DPS engaged contractors to design the works. While contracting arrangements are discussed in more detail in later chapters, the three key contractors for the design phases were:

- Group One — the design phase was led by an architectural firm, commenced in December 2014 and the finalisation date was not able to be ascertained;

- Group Two managing contractor (physical security) — the design phase was led by the managing contractor, commenced in April 2016 and was finalised in March 2017; and

- Group Two head contractor (electronic security) — the design phase was led by the head contractor, commenced in May 2016 and was finalised in November 2016.

Design process

2.37 DPS identified in June 2015 that there was not a defined design process for the Group One works, and this had led to the need for redesign. The project completion report for these works noted that ‘there was a relatively high incidence of issues and associated variations relating to poor/incomplete design’. DPS identified the following issues relating to the design process for the Group One works.

- There were delays in completing the design work.

- There was a lack of a defined design process, including approval processes.

- A poor standard of design documentation resulted in inaccurate cost plans and design solutions that did not align with the user requirements and significantly exceeded the budget.

2.38 For the Group Two works — physical security and electronic security — the design phase involved the development of a range of documentation, including detailed design documents. These documented the design phase activities including: preliminary analysis and designs; scheduling and cost plans; design reports, drawings and specifications; and project plans. DPS assessed Group Two contractors as performing effectively in terms of the design.

Design integrity and heritage

2.39 While not listed on the National Heritage List52, Parliament House is a nationally significant building. The design integrity and heritage values of Parliament House are an important consideration for DPS.

2.40 DPS identified the potential for the security works to impact the heritage of the building, and the potential for an inability to resolve competing security and heritage requirements to affect the works. As a result, DPS stipulated the need for stakeholder engagement and articulation of design integrity and heritage requirements as part of the design process. However, while DPS advised that planning legislation set requirements, DPS did not document its internal design integrity process or heritage consideration process for the security works.53

2.41 Heritage Impact Assessments were the primary mechanism through which heritage considerations were assessed. The purpose of the assessments was to identify and document how the security works may impact on the heritage values of Parliament House and to propose measures to mitigate those impacts. Thirty-one of 34 works had a heritage impact assessment.54

Moral rights

2.42 Moral rights under the Copyright Act 1968 give creators of artistic works — including architecture and design — legal rights over dealings with their work.55 DPS identified the need to consult with Parliament House’s moral rights holder, given the extent of the security works. DPS consulted with the moral rights administrator for each of the groups of work.

2.43 Box 2 provides an overview of the design approach adopted for one project — the construction of a fence/barrier around Parliament House.

|

Box 2: Perimeter security design integrity and heritage |

|

The perimeter security enhancements were part of the Group Two (physical security) works and included fences and various other barriers around Parliament House. DPS recognised that the proposed design for this project could impact on the design integrity of the building and sought a variety of design options. In March 2016, a Heritage Impact Assessment was undertaken, with an addendum in October 2016 to assess the revised design. The assessment concluded that the degree of impact on the heritage values from the proposed fencing to the front and rear of the building would be: moderate; long term; medium scale; and moderate intensity. It noted that:

A similar assessment was made of the proposed landscape barriers.

Both Houses of Parliament approved the design for the project in December 2016. |

Approvals

2.44 DPS provided evidence to demonstrate that 17 of the 34 works were appropriately approved, either by the Presiding Officers or the Parliament. DPS did not provide approval documentation for the remaining 17 works.

3. Procurement

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Parliamentary Services (DPS) effectively procured suppliers to deliver the security upgrade capital works program (the program).

Conclusion

DPS was largely effective in procuring suppliers to deliver the program. Procurement action complied with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules. Contract formation was consistent with Commonwealth standards, although with potential risks in the areas of timely execution, and there were gaps in the documentation of contractual management arrangements.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO identified areas for improvement in contract formation and contractual management arrangements.

3.1 The ANAO examined whether DPS:

- complied with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules; and

- established effective contracts with suppliers.

Did DPS comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules?

DPS complied with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules for the head contract procurements examined by the ANAO. Procurement processes were guided by procurement strategies, approaches to market met requirements, and open tenders were evaluated in accordance with tender evaluation plans to ensure value for money.

3.2 As a non-corporate Commonwealth entity under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (the PGPA Act), DPS must conduct procurement in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). The CPRs are supported by guidance issued by the Department of Finance. The ANAO primarily examined six head contract procurement processes (see Table 3.1).

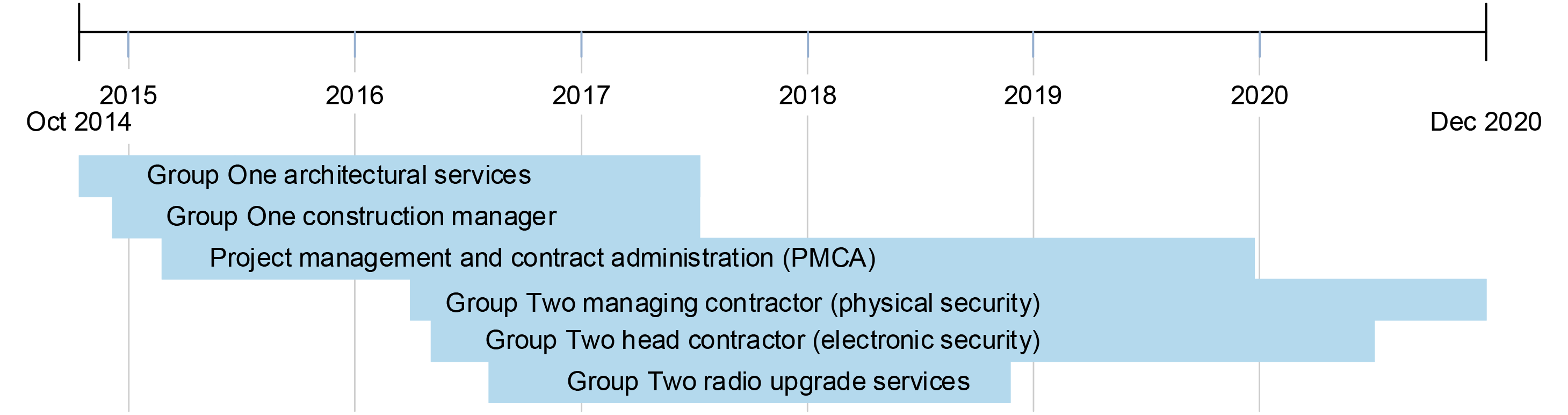

Table 3.1: Six head contract procurements for Group One and Group Two works

|

Contract |

Description |

|

Contract one |

Group One architectural services |

|

Contract two |

Project management and contract administration (PMCA) |

|

Contract three |

Group One construction manager |

|

Contract four |

Group Two managing contractor (physical security) |

|

Contract five |

Group Two head contractor (electronic security) |

|

Contract six |

Group Two radio upgrade services |

Source: ANAO, based on DPS documentation.

Procurement Planning

3.3 DPS undertook procurement processes for the contracts examined by the ANAO over the period from October 2013 to September 2016. During this time, the July 2012 and July 2014 versions of the CPRs were in force. In April 2015, DPS introduced a new suite of documents including a DPS Procurement Manual, DPS Procurement Officer Manual, Procurement Risk Management Plan, and templates for seeking procurement approvals.

3.4 From the outset of the program, DPS recognised that the program would need to comply with CPR requirements. Department of Finance guidance states that the first steps in a procurement process are to plan the procurement based on an identified need, and to scope the procurement.56

3.5 In the context of an expedited planning and procurement process — from the external security assessments in September 2014, to the funding proposal in November 2014 and the procurement approval in early December 2014 — DPS included procurement strategies for the Group One construction manager contract and the project management and contract administration (PMCA) contract in the respective decisions to approve the approach to market.

3.6 For Group Two works, DPS developed a procurement strategy to identify each of the procurement activities to be undertaken.57 The strategy covered physical security, electronic security, and various consultancies. DPS approved the strategy on 29 May 2015, after endorsement by the Program Board, and following approval of the program management plan. DPS also maintained a procurement management plan for the program, which was intended to be reviewed six monthly and was revised twice between 2015 and 2018. DPS prepared a separate procurement strategy for the radio upgrade services contract.

3.7 Procurement strategies for contracts two to six (see Table 3.1) outlined the plan for and scope of the procurements as recommended by Department of Finance guidance, and outlined objectives and rationales for the procurements. A procurement risk assessment for Group One works identified 13 risks, all assessed at a low risk rating.58 The Group Two procurement strategy identified eight potential risk events that were not assigned a risk rating.

3.8 A 2015 internal audit found that the Group One strategies outlined the proposed procurement methods, timeframes and steps required to ensure compliance with the CPRs, the PGPA Act and DPS policy.

3.9 The Group Two procurement strategy was further developed and more detailed, with evidence of more project planning and market research having been undertaken.

Procurement methods

3.10 Department of Finance guidance states that the next step in a procurement process is to determine the procurement method — for example, limited or open tender.59 The CPRs require that procurement of construction services above a procurement threshold of $7.5 million must be conducted in accordance with Division 2 additional rules, unless an exemption applies.

3.11 DPS initially decided to proceed to limited tender for Group One construction management works in December 2014, and for the PMCA in February 2015. In both cases, DPS sought advice from the Department of Finance to confirm the validity of relying on CPR paragraph 10.3b (reasons of extreme urgency)60 to conduct a limited tender. The limited tender approach was agreed at the SES Band 2 level in reliance on paragraph 10.3b, the identified need to complete high priority works immediately, and the low risk profile of Group One works. Both procurement actions subsequently used panel arrangements managed by another agency (see paragraph 3.18).

3.12 Prior to the program, DPS had conducted an open tender for architectural services in 2013–14. DPS conducted open tender procurements for the Group Two managing contractor (physical security), Group Two head contractor (electronic security) and the Group Two radio upgrade services contracts, as these procurements were above the relevant procurement thresholds.

3.13 A key element of procurement design is the integration of probity considerations into all aspects of the procurement, to ensure ethical procurement and the proper use and management of public resources.61 In September 2015, an internal audit examining Group One works found that a probity plan had not been developed for those works; however, a probity advisor was engaged for Group Two works. The Group Two managing contractor (physical security), Group Two head contractor (electronic security) and Group Two radio upgrade services procurements all had probity plans.

Approach to Market

3.14 For the Group One construction manager approach to market, DPS requested the building architect to nominate one or more providers with whom they had worked previously, and approached the one nominated provider. This approach was taken to ensure the nominated provider had demonstrated experience in undertaking works at Parliament House, an understanding of the inherent infrastructure issues of the building and to minimise coordination risks between design and construction. The nominated provider was engaged from a construction management services panel managed by another agency (see paragraph 3.18).

3.15 DPS also identified two potential providers for the PMCA contract from a panel arrangement managed by the Australian Federal Police.

3.16 DPS conducted open tenders published on the Australian Government’s procurement information system, AusTender, for the Group One architectural services, Group Two managing contractor (physical security), Group Two head contractor (electronic security), and Group Two radio upgrade services procurements.

3.17 DPS provided information to tenderers by way of request documentation, with additional information provided by means of amendments to the initial approach to market circulated to all tenderers, and — for two of the four procurements — industry briefings.62 The approaches to market complied with minimum time limits, and DPS did not accept any late submissions. DPS sought and received advice from the Department of Finance to ensure sensitive material was not disclosed in the request documentation, and some information was only released to potential tenderers upon completion of a disclaimer and confidentiality agreement.63

Evaluation

3.18 For the Group One construction manager procurement process, DPS agreed to a limited tender procurement approach on 5 December 2014, awarded the contract on 9 December 2014, and executed the contract on 18 December 2014. A single provider submitted a fee proposal under a panel arrangement managed by the Australian Federal Police that was established by open tender. A 2015 internal audit found this approach reasonable in the circumstances, and found that the method of procurement through the panel was in accordance with the CPRs but the documentation maintained for the procurement could have more accurately reflected the method of procurement and process followed.

3.19 DPS could have adopted a more robust approach to the consideration of price and whole of life costs in the Group One construction manager procurement, as the panel arrangement was relied on for the value for money assessment of the fees. However, this related only to the construction management fee ($349,453) and not the related trade costs that were delivered under the contract (estimated at the time to be $4 million).

3.20 The PMCA procurement process also used a panel arrangement, and evaluated two proposals.

3.21 For the Group One architectural services, Group Two managing contractor (physical security), Group Two head contractor (electronic security), and Group Two radio upgrade services procurement processes, DPS developed Tender Evaluation Plans in consultation with internal procurement and external legal and probity advisers. Tender Evaluation Plans recorded evaluation committee members and advisers by role, set out the responsibilities of the chair and committee members, and outlined the evaluation process including the weighted evaluation and value for money criteria. Tender Evaluation Plans set out the evaluation criteria for the procurement, but the criteria did not always include the mandatory considerations set out in clause 4.5 of the CPRs: environmental sustainability; and whole-of-life costs.

3.22 Evaluation committees for these four procurement processes provided evaluation reports to the delegated decision maker to take into account in approving negotiations with the selected contractor. Evaluation reports set out committee recommendations, based on a value for money assessment against evaluation criteria, and took into account risk as part of the balanced assessment, as required by the CPRs. The committees took into account relevant experience and performance history of tenderers for all four procurements. Evaluation reports set out the evaluation process, confirmed conformance with the Tender Evaluation Plan, and evaluation reports for the Group Two managing contractor (physical security) and Group Two head contractor (electronic security) processes included a probity report from the probity adviser.

Did DPS establish effective contracts with suppliers?

DPS established effective contracts with suppliers, using Australian Government templates for all six head contracts and 12 of 13 consultancies and other contracts examined. Records management and timely execution of contracts were areas for improvement. Contract management plans were in place for three head contracts, although DPS did not have contract management and associated plans for all head contracts, as recommended by internal policy.

3.23 The ANAO examined six head contracts (see paragraph 3.2) — and 13 consultancies and other contracts procured directly by DPS and worth a combined total of almost $2 million — to determine whether DPS established effective contractual arrangements with suppliers. The ANAO examined contractual provisions and approval processes for subcontracting, but did not examine individual subcontracts.

Establishing effective contracts

Contract formation

3.24 All six head contracts used Australian Government contract templates as the basis for contract negotiation and formation, with the form of contract depending on the procurement method used. Table 3.2 sets out the form of contract for the six head contracts.64

Table 3.2: Forms of head contract for six head contracts

|

Contract |

Form |

|

One — Group One architectural services |

Deed of standing offer and work orders |

|

Two — Project management and contract administration (PMCA) |

Deed of standing offer and official orders |

|

Three — Group One construction manager |

Deed of standing offer and building works contract |

|

Four — Group Two managing contractor (physical security) |

Commonwealth managing contractor contracta |

|

Five — Group Two head contractor (electronic security) |

Commonwealth head contractor contracta |

|

Six — Group Two radio upgrade services |

Digital sourcing model contract |

Note a: The Group Two managing contractor and the Group Two head contractor contracts were based on the Defence Estate Quality Management System Suite of Facilities Contracts: https://www.defence.gov.au/estatemanagement/Support/SuiteContracts/default.asp.

Source: DPS documents.

3.25 The ANAO also examined 13 consultancies and other contracts procured by DPS between 15 October 2014 and 22 January 2018 and found that all but one used Commonwealth contracts, work orders under deeds of standing offer, or panel arrangements. Since 1 January 2016, it has been mandatory for non-corporate Commonwealth entities such as DPS to use the Commonwealth Contracting Suite (CCS) for procurements under $200,000, unless exceptions apply. Of five contracts examined that were entered into since 1 January 2016, three contracts were exceptions to the requirement (two were above the $200,000 threshold and one was from a panel procurement arrangement), and the remaining two contracts used the CCS.

3.26 At the start of the program, records were saved in DPS system workgroup files. In 2016, DPS started to migrate record keeping to electronic records management software, but workgroup files remained in active use throughout the program into 2020 and had not been fully migrated at the time of the audit. Program records were also kept on proprietary project management software and were not fully migrated into DPS records management software at the time of the audit. DPS did not appropriately maintain a contract register for contractual documents within the program. The diversity in records management approaches meant that DPS was not able to readily access signed copies of contracts and associated program documents in a timely manner.

3.27 The execution of contracts after work has commenced can create legal risk for contracting entities, particularly if work is undertaken outside the scope of the written contract.

- From the six head contracts and 15 work orders, seven instances were identified where work orders under the head contracts were executed between one and 42 calendar days after work orders required work to be undertaken and one undated instance, worth a combined total of around $1.5 million.

- For the Group Two radio upgrade services contract, one component of an authorised variation reimbursed a contractor for $26,195 of expenses (representing 4.2 per cent of the contract price) already incurred prior to variation execution.

- Out of 13 consultancies and other contracts reviewed, the ANAO identified five instances of contracts or extensions that were executed between three and 36 calendar days after contracts required work to be undertaken, one instance executed after almost 18 months, and two instances that were undated, worth a combined total of almost $1 million.65

Contractual performance expectations

3.28 Each of the six head contracts specified objectives and deliverables, and detailed milestones were clearly specified in four of the six contracts (not in the Group One architectural services or Group One construction manager contracts).

Use of third parties

3.29 Service delivery may require the engagement of third parties, such as subcontractors. The Commonwealth Procurement Rules and Australian Government Contract Management Guide66 outlines requirements and guidance for the use of particular contract clauses relevant to the use of third parties. Of the six contractual clauses examined (see Table 3.3), five were better practice and not mandatory, with public disclosure of subcontractor participation being the only mandatory required clause.

3.30 In each of the six head contracts, service delivery was restricted to specified personnel and/or nominated subcontractors, and there were limitations on assignment. All six head contracts required written approval from DPS to use additional subcontractors. There was evidence of the inclusion of subcontractor details in work orders for the Group One architectural services and in the official order for PMCA. The Group One construction manager was contracted to undertake all procurement for the works and to obtain subcontracting approval from DPS, contract directly with subcontractors for trade packages and materials on DPS behalf, and was responsible for all works. There was no nominated subcontractors included in the contract. The Group Two managing contractor (physical security) and Group Two head contractor (electronic security) were contracted to seek approval from DPS prior to tendering for reimbursable or provisional work, to obtain subcontracting approval from DPS, and contract directly with subcontractors. Nominated subcontractors were detailed in the contract. DPS was not able to provide evidence that it had approved any subcontractors, and advised that subcontracting approval generally occurred in the form of variations to the contract.

Table 3.3: Third party arrangements in six head contracts

|

Contractual provisions |

Onea |

Twoa |

Threea |

Foura |

Fivea |

Sixa |

|

Written permission required to use additional subcontractors |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

|

Limitations on assignmentb |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

|

Limitations on novationc |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

■ |

■ |

◆ |

|

Public disclosure of subcontractor participationd |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

◆ |

|

‘Back-to-back’ contractinge |

◆ |

■ |

◆ |

■ |

■ |

▲ |

|

No reduction in head contractor’s contractual obligationsf |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

▲ |

▲ |

▲ |

Legend: ◆ contract provision sets out arrangements largely or fully. ▲ contract provision sets out arrangements partly. ■ contract does not include a provision that sets out the arrangements.

Note a: Table 3.2 details the relevant contracts.

Note b: Assignment refers to the situation ‘where the supplier wishes to transfer some or all of its rights under the contract to a third party that is not currently a party to the contract. There may be risks to the customer if the supplier is permitted to assign some or all of its rights to a third party that has not been through the scrutiny of a procurement process’ (https://www.finance.gov.au/government/procurement/clausebank/assignment).

Note c: Novation is where an ‘incoming third party supplier will be taking over part or full responsibility of the contract, as if it has been a party to the Contract since the commencement’ (https://www.finance.gov.au/government/procurement/clausebank/novation-and-assignment).

Note d: Agencies must require contractors to agree to the public disclosure of the names of any subcontractors engaged to perform services in relation to a contract, Commonwealth Procurement Rules — July 2012 and July 2014, paragraph 7.19.

Note e: The practice of including obligations from a head contract in subcontracts to make the subcontractor legally responsible for elements of project delivery.

Note f: A contract provision that ensures that the use of subcontractors do not result in a reduction in the head contractor’s contractual obligations to DPS.

Source: ANAO, based on DPS documents.

Liability frameworks and protections for the Australian Government

3.31 The CPRs require that entities consider risks when making decisions relating to the terms of the contract, and that entities should generally not accept risk which another party is better placed to manage.67 Table 3.4 sets out liability frameworks and the relevant protections for the Australian Government in the six head contracts, examining five better practice and non-mandatory contract clauses.

Table 3.4: Liability frameworks in six head contracts

|

Contractual provisions |

Onea |

Twoa |

Threea |

Foura |

Fivea |

Sixa |

|

Audit and accessb |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

|

Performance assurance (securities)c |

– |

– |

▲ |

◆ |

◆ |

– |

|

Performance assurance (liquidated damages)c |

– |

– |

▲ |

– |

◆ |

– |

|

Indemnities and insuranced |

◆ |

◆ |

▲ |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

|

Dispute resolution and termination |

◆ |

◆ |

▲ |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

Legend: ◆ contract provision sets out liability requirement largely or fully. ▲ contract provision sets out liability requirement partly. – non-mandatory liability requirement was not included in the contract.

Note a: Table 3.2 details the relevant contracts.

Note b: An audit and access clause can preserve the rights of agencies to access contractor premises and inspect records associated with the contract.

Note c: It is not mandatory to use securities or liquidated damages provisions in Commonwealth contracts, and their use will reflect a decision by the entity based on the nature and risk of the contract.

Note d: Entities can manage legal risks by requiring contractors to indemnify the Commonwealth, and to hold insurance such as public liability, professional indemnity and workers’ compensation insurance.

Source: ANAO, based on DPS documents.

Establishing effective contract management arrangements