Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Treasury’s Design and Implementation of the Measuring What Matters Framework

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The Australian Government released Measuring What Matters (MWM) in July 2023. MWM is a national wellbeing framework intended to track Australia’s progress that extends beyond purely economic measures.

- This audit provides assurance to the Parliament of the Department of the Treasury’s (Treasury) effectiveness of the design and implementation of MWM.

Key facts

- The MWM framework sets out five themes supported by 12 dimensions that describe aspects of the wellbeing themes and 50 key indicators, to monitor and track wellbeing progress, which will be updated over time.

- The MWM statement and MWM dashboard are two mechanisms that report on and monitor progress of indicators and metrics underlying the MWM framework.

- As of April 2024, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) assumed responsibility for the annual MWM dashboard update.

What did we find?

- The design and implementation of the MWM framework was largely effective. While Treasury had provided sound policy advice and considered practical implementation, it did not have arrangements in place to assess if MWM was meeting its policy objective.

- The design of the MWM framework was largely effective.

- The arrangements to support implementation were largely effective.

What did we recommend?

- There were two recommendations to Treasury to improve: monitoring and evaluation of how MWM is being embedded across government; and arrangements for delivering and publishing the next MWM statement.

- Treasury agreed to the two recommendations.

283

Public submissions during the design of MWM

71

Meetings with stakeholders during the design of MWM

$14.8 m

For the ABS to reinstate and enhance the General Social Survey

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. In July 2023, the Australian Government released a national wellbeing framework called Measuring What Matters (MWM). The Department of the Treasury (Treasury), as the policy owner for MWM, described the purpose for MWM was to construct a more complete picture of societal progress and enable government to better set and communicate policy priorities. Treasury stated a national wellbeing framework was important for better measurement of the progress of all Australians beyond economic measures. Treasury identified five themes for MWM — healthy, secure, sustainable, cohesive and prosperous — supported by 12 dimensions that describe aspects of the wellbeing themes and 50 key indicators1, to monitor and track progress, which will be updated over time.2

Rationale for undertaking the audit

2. The Australian Government has stated that MWM is ‘an important foundation on which we can build — to understand, measure and improve on the things that matter to Australians’.

3. This audit provides assurance to Parliament that the MWM framework was effectively designed and developed; and that Treasury’s arrangements to support implementation are effective.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Treasury’s design and implementation of the Measuring What Matters framework.

5. To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were examined.

- Did Treasury effectively design and develop Measuring What Matters?

- Are arrangements to support the implementation of Measuring What Matters effective?

Conclusion

6. Treasury was largely effective in designing and implementing the Measuring What Matters framework. While Treasury had provided sound policy advice and considered practical implementation, it did not have arrangements in place to assess if MWM was meeting its policy objective.

7. Treasury was largely effective in its design and development of MWM. MWM was supported by sound policy advice and considered practical policy implementation. There was no evaluation plan to measure the effectiveness of the MWM framework. Treasury conducted stakeholder consultation with government and non-government bodies domestically and internationally. Treasury did not document the rationale for how themes and indicators were selected based on the consultation feedback.

8. Treasury had largely effective arrangements in place to support the implementation activities for embedding MWM. Treasury facilitates discussions on MWM across government through an interdepartmental committee. Treasury has made progress to embed MWM into policy design and consulted with the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) to improve the data quality. There are no arrangements in place to monitor, report or evaluate whether MWM is achieving its intended policy objective. The second MWM statement is intended to be released in 2026. Treasury does not have arrangements in place to facilitate the publication of the next MWM statement.

Supporting findings

Design and development

9. Treasury defined the intent of the policy and how outcomes would be measured. Treasury considered ways of integrating quantitative data into the MWM framework, and analysed information to select indicators based on qualitative data and quantitative measures. The policy advice identified risk and potential mitigation strategies. Treasury did not document decisions made to show linkages between data analysis and conclusions. (See paragraphs 2.2 to 2.22)

10. Treasury researched and consulted on other wellbeing frameworks used globally, and tested indicators with other government entities to determine if indicators were practical to implement. The design process considered policy evaluation in relation to indicators. Treasury is considering how to embed the MWM framework into policy-making processes. There is no evaluation plan in place to measure the effectiveness of the MWM framework. (See paragraphs 2.23 to 2.30)

11. Before the release of MWM in July 2023, Treasury consulted with stakeholders to design the themes, dimensions and indicators. The consultation consisted of meetings with government and non-government bodies domestically and internationally; and two public submission rounds. Treasury provided public updates throughout the consultation process. Treasury received feedback from the public wanting more time for consultations. Treasury did not document the rationale for how themes and indicators were selected based on the consultation feedback. (See paragraphs 2.31 to 2.71)

Planning for implementation

12. Treasury established an interdepartmental committee to facilitate discussions and seek feedback on MWM across government. Treasury worked with the ABS to provide advice to government and received funding for the ABS to reinstate and expand the General Social Survey as a dedicated survey for MWM. Treasury has made progress to embed MWM into policy design across government. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.37)

13. There are no monitoring or evaluation arrangements in place to measure the embedding of MWM across government. Treasury provides reports externally through the MWM dashboard and statement. The second MWM statement is intended to be released in 2026. Treasury does not have arrangements in place to facilitate the development and publication of the next MWM statement. (See paragraphs 3.38 to 3.48)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 3.42

To ensure Measuring What Matters is achieving its desired outcome, the Department of the Treasury establish arrangements for monitoring and evaluating how Measuring What Matters is being embedded across government to achieve its intended outcome.

Department of the Treasury’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.48

The Department of the Treasury implement arrangements for developing and publishing the next Measuring What Matters statement.

Department of the Treasury’s response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

14. The proposed audit report was provided to Treasury. Treasury’s summary response is reproduced below. The full response from Treasury is at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

Treasury welcomes the report’s conclusion that it was largely effective in providing advice to Government regarding the design and implementation of the Measuring What Matters framework. Treasury welcomes the key messages that it provided sound policy advice, considered practical implementation of the framework and consulted broadly at all stages of design and implementation.

Treasury agrees with the recommendations presented in the report. As part of the work to implement Measuring What Matters, Treasury will establish arrangements for monitoring and evaluating progress toward achieving its intended outcomes and will design a plan to develop and publish the 2026 Measuring What Matters Statement.

Implementation and closure of these recommendations will be monitored by our Audit and Risk Committee.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

15. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Stewardship of strategies, policies and frameworks

Shared delivery and shared risk

Record keeping

1. Background

Introduction

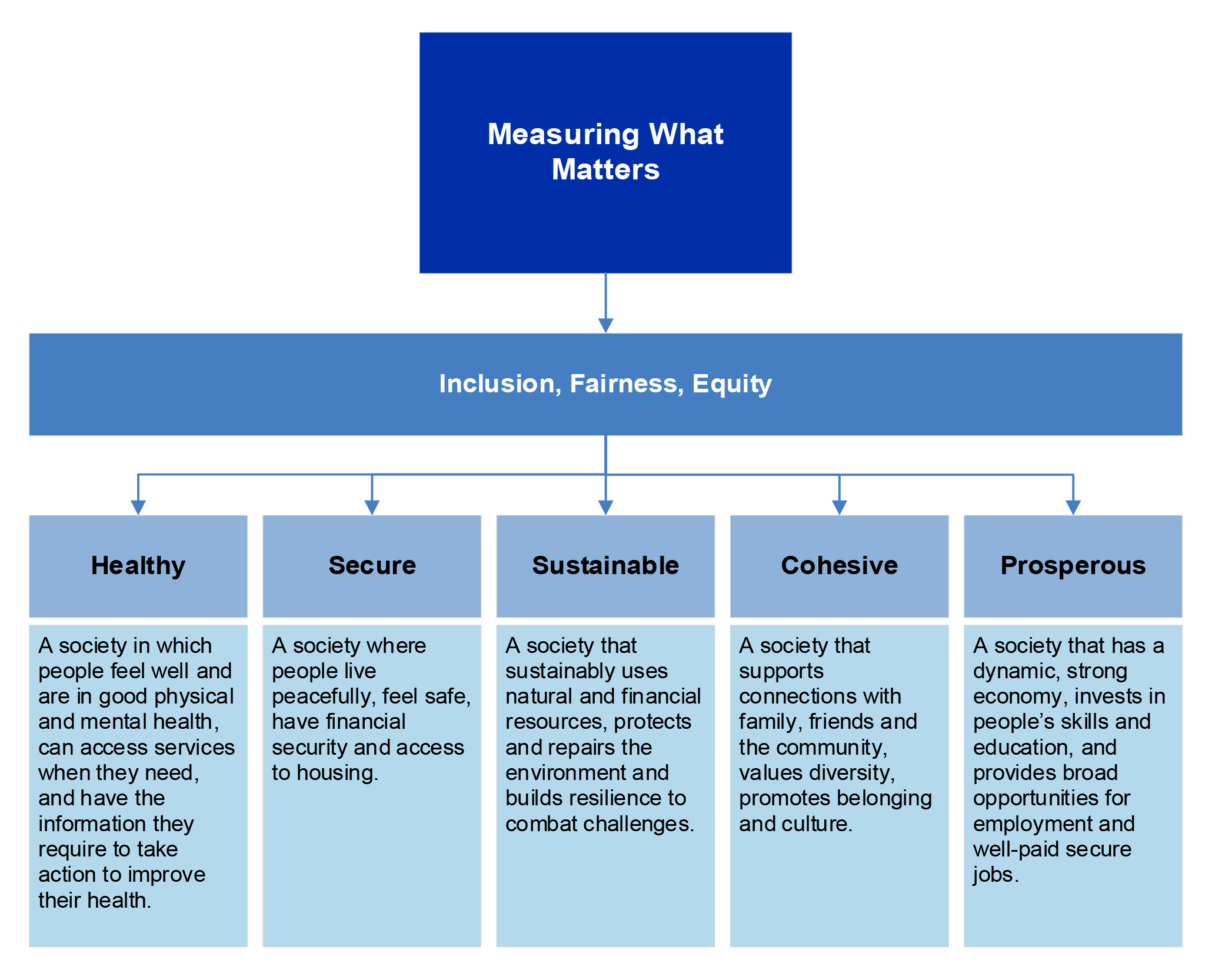

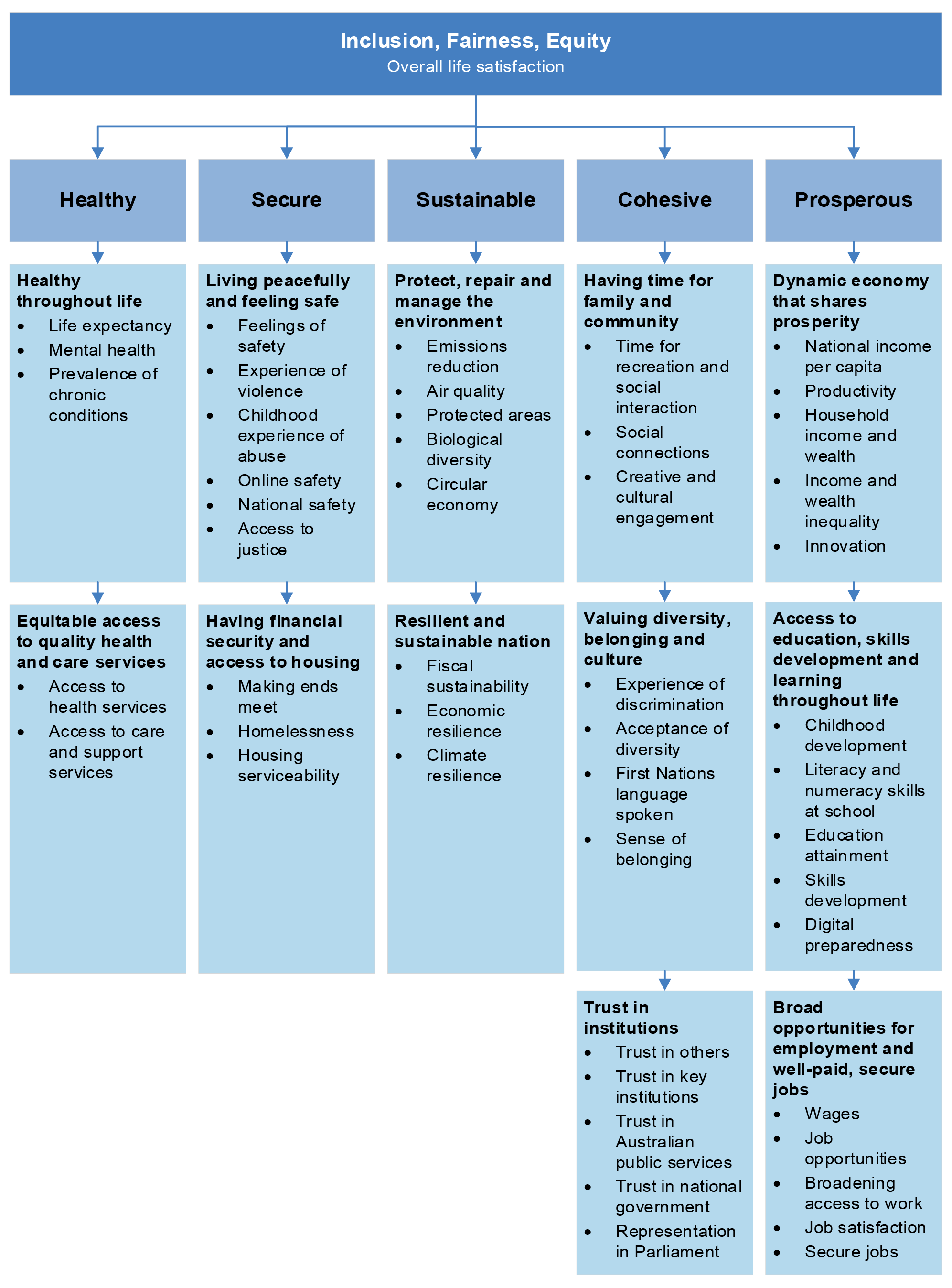

1.1 In July 2023, the Australian Government released a national wellbeing framework called Measuring What Matters (MWM). First outlined in the 2022–23 October Federal Budget, MWM was announced as ‘important for tracking and achieving progress’ by ‘bringing attention to the broader factors that underpin community wellbeing and longer-term economic prosperity’.3 The Australian Government presented factors in MWM ‘that are important to Australians’ individual and collective wellbeing across all phases of life’.4 Inclusion, fairness and equity are described as cross-cutting dimensions that span across the five themes — healthy, secure, sustainable, cohesive and prosperous (see Figure 1.1). The Department of the Treasury (Treasury) identified five themes supported by 12 dimensions that describe aspects of the wellbeing themes and 50 key indicators5, to monitor and track progress, which will be updated over time (see Appendix 3).6

Figure 1.1: Measuring What Matters Framework

Source: ANAO summary of public documentation.7

1.2 Wellbeing frameworks have been described by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as being able to assist governments with monitoring societal progress and better informing policy decisions by providing indicators and metrics ‘across multiple dimensions that matter for people, the planet and future generations’ that extend beyond purely economic measures, such as Gross Domestic Product.8 Internationally, governments have been increasingly recognising the value of broader measures of wellbeing. Countries such as Canada, Germany, New Zealand, Scotland and Wales have used wellbeing frameworks to raise the profile of non-economic outcomes and to improve policy-making (see Table 1.1).9

Table 1.1: Examples of international national progress and wellbeing frameworks

|

Country |

Framework name |

Year introduced |

No. of policy areas |

No. of indicators |

|

Scotland |

National Performance Framework |

2007 |

11 |

81 |

|

Italy |

Measures of Equitable and Sustainable Wellbeing |

2010 |

12 |

153 |

|

United Kingdom |

Measures of National Wellbeing |

2010 |

10 |

38 |

|

New Zealand |

Living Standards Framework |

2011 |

22 |

103 |

|

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)a |

Measuring Wellbeing and Progress |

2011 |

15 |

82 |

|

Wales |

Wellbeing of Wales |

2015 |

7 |

46 |

|

Germany |

Wellbeing in Germany |

2017 |

12 |

46 |

|

Canada |

Quality of Life Framework |

2019 |

14 |

83 |

|

Iceland |

Wellbeing in Iceland |

2019 |

13 |

39 |

|

Australiab |

Measuring What Matters |

2023 |

5 |

50 |

Note a: While the OECD has 36 headline indicators, it also has 46 sub-indicators, bringing the total to 82.

Note b: Before Measuring What Matters, there were two wellbeing initiatives in Australia: Measures of Australia’s Progress (see paragraph 1.5) and the Department of the Treasury’s Wellbeing Framework (see paragraph 1.9).

Source: ANAO summary from the 2022–23 October Federal Budget Statement 4 and Measuring What Matters Statement.

1.3 Box 1 provides an example of a wellbeing framework being integrated into decision-making processes.

|

Box 1: Wellbeing budgets — New Zealand and international developments |

|

A few countries have wellbeing frameworks integrated with decision-making processes, such as Budgets. For example, New Zealand’s ‘Living Standards Framework’ includes:

New Zealand has required all new policy proposals to specify their contribution to wellbeing and be evaluated on this basis. |

Source: 2022–23 October Federal Budget Statement 4.

Past wellbeing initiatives in Australia

Measures of Australia’s Progress

1.4 In October 2001, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) published, Measuring Wellbeing: Frameworks for Australian Social Statistics.10 This explained how social statistics were organised by the ABS under a broad framework covering ‘nine areas of concern’: population; family and community; health; education and training; work; economic resources; housing; crime and justice; and culture and leisure.11

1.5 In 2002, the ABS released Measuring Australia’s Progress (MAP), later called Measures of Australia’s Progress from 2004, which focused on a series of economic, environmental, and social indicators to ‘depict national progress’ by determining:

- the major direct influences on the changing wellbeing of the Australian population;

- the structure and growth of the Australian economy; and

- the environment - important both as a direct influence on the wellbeing of Australians and the Australian economy, and because people value it in its own right.12

1.6 Treasury stated in 2012:

The Measures of Australia’s Progress project of the Australian Bureau of Statistics was ahead of its time, and continues to provide an insightful, wide-ranging and balanced dashboard of important indicators to assist public debate and understanding. This dashboard approach is the best way to grapple with perhaps the most important and challenging measurement question there can be. 13

1.7 The ABS announced it would discontinue the MAP, along with other changes to its work program, on 5 June 2014 to ‘reduce expenditure’, citing it ‘had to discontinue or reduce outputs in areas that are valued by the users of those statistics’ and stated if ‘funding is provided for the work we are ceasing, we will reinstate it’.14

1.8 In recent years, the Australian Government and state and territory governments have published many progress and wellbeing indicators in reports, agreements, and dashboards, with the aim to support decision-making and accountability for certain policy areas and provide a view to improving outcomes for the Australian people. Some examples are the Closing the Gap15 and the State of the Environment reports.16

Treasury’s Wellbeing Framework

1.9 A wellbeing framework was put in place by Treasury in 2004 and revised in 2011.17 The framework considered five dimensions of wellbeing:

- the set of opportunities available to people;

- distribution of those opportunities across Australians;

- the sustainability of those opportunities over time;

- overall risk level and allocation borne by individuals and the community; and

- complexity of choices faced by individuals and the community.18

1.10 The Treasury mission statement from October 1997 until 201819 stated its objective was ‘to improve the wellbeing of the Australian people by providing sound and timely advice to the government, based on objective and thorough analysis of options, and by assisting the Treasury ministers in the administration of their responsibilities and the implementation of government decisions’.20 References to the objective to ‘improve wellbeing of the Australian people’ last appeared in Treasury’s outcome statement in its 2017–18 annual report.21

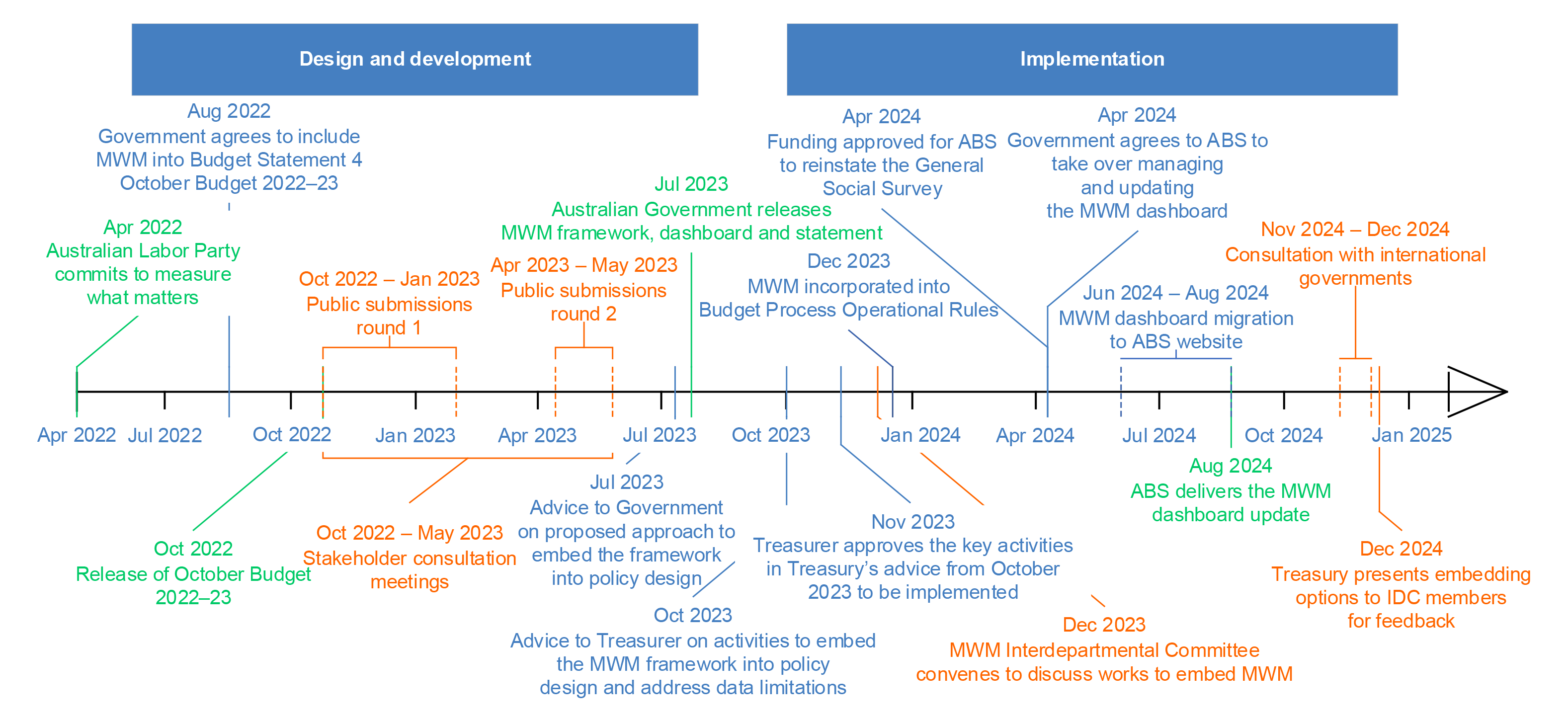

Measuring What Matters

1.11 In April 2022, the Australian Labor Party made an election commitment in its Statement on Labor’s economic plan and budget strategy to ‘Measur[e] what matters through a Budget that measures progress and wellbeing and a more robust Intergenerational Report in the middle year of every term’.22 Budget Statement 4 — Measuring What Matters in the 2022–23 October Federal Budget announced the Australian Government’s intention to develop and release in 2023 a national wellbeing framework ‘tailored to Australia’.23

1.12 The design and development of a national wellbeing framework was led by Treasury. Treasury described a national wellbeing framework as important to allow for better measurement of the progress of all Australians, beyond economic measures. Treasury led a consultation process from October 2022 to May 2023. This consisted of:

- seventy-one meetings with at least 65 different stakeholders; and

- two public consultation rounds, which received 283 responses.

1.13 MWM was released in July 2023 after Treasury analysed the feedback from the consultation process to design and develop it. MWM consists of the framework. The MWM statement and data dashboard are two mechanisms to report on and monitor progress of indicators and metrics underlying the MWM framework. Measuring What Matters ‘is a living framework that will continue to evolve and improve over time to reflect ongoing feedback from the community, new research, improved data availability, and changing community views’.24

1.14 The MWM statement provided a high-level performance report across the five themes and their respective indicators. It also highlighted the next steps for MWM, which would involve:

- exploring data disaggregation to better reflect different groups; and

- identifying opportunities to embed the framework into government decision making and beyond the public sector; so it could be ‘drawn upon by business, academia, and the community, to support their efforts to create better lives for all Australians’.25

1.15 The 2024–25 Federal Budget states that the ABS will deliver an enhanced General Social Survey to support MWM.26 After the release of the first MWM dashboard by Treasury in July 2023, reporting of annual progress against the framework was transferred from Treasury to the ABS in April 2024.27 The dashboard was updated and published on the ABS website in August 2024.28

1.16 In December 2023, Treasury included a statement in the Budget Process Operational Rules to alert entities to consider MWM.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.17 The Australian Government has stated that MWM is ‘an important foundation on which we can build — to understand, measure and improve on the things that matter to Australians’.29

1.18 This audit provides assurance to Parliament that the MWM framework was effectively designed and developed; and that Treasury’s arrangements to support implementation are effective.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.19 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Treasury’s design and implementation of the Measuring What Matters framework.

1.20 To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were examined.

- Did Treasury effectively design and develop Measuring What Matters?

- Are arrangements to support the implementation of Measuring What Matters effective?

1.21 The audit does not include an examination of the effectiveness of wellbeing frameworks that apply to a particular region, group of people or sector, nor the effectiveness of surveys and data collection undertaken by other entities, like the ABS, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, other government departments; and publicly available data from sources such as the Lowy Institute. The full list of data custodians for MWM data sources is available at Appendix 4.

Audit methodology

1.22 The audit methodology included:

- meeting relevant Treasury staff and staff of other government entities involved in the preparation and implementation of MWM; and

- review of stakeholder consultation documents and analysis, submissions from the Treasury consultation processes and entity records.

1.23 The audit was open to contributions from the public. The ANAO received and considered four submissions from the public.

1.24 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $392,695.

1.25 The team members for this audit were Elvira Manjaji-Baxter, Eb Chomkul, Madigan Paine, Nathan Callaway and David Tellis.

2. Design and development

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) effectively designed and developed Measuring What Matters (MWM).

Conclusion

Treasury was largely effective in its design and development of MWM. MWM was supported by sound policy advice and considered practical policy implementation. There was no evaluation plan to measure the effectiveness of the MWM framework. Treasury conducted stakeholder consultation with government and non-government bodies domestically and internationally. Treasury did not document the rationale for how themes and indicators were selected based on the consultation feedback.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO suggested that Treasury could improve: record keeping of key decisions and business activities; and consistency of information communicated to the public.

2.1 Treasury led the design and development of MWM. The Australian Public Service Commission’s (APSC) Delivering Great Policy Model30 has the following key elements that contribute to developing great policy advice:

- ensuring that policy and program design is informed by a robust evidence-base, sound analysis, and clear links to the achievement of policy objectives;

- involving key stakeholders within and outside the APS to ensure that government initiatives are reflective of diverse views and have broad support31;

- identifying and considering the key risks to design and implementation at early stages of policy development to support informed decision-making as initiatives are established and implemented32; and

- implementation plans should identify deliverables and milestones and embed evaluation at the outset.

Was Measuring What Matters supported by sound policy advice, including plans for assessing the achievement of outcomes?

Treasury defined the intent of the policy and how outcomes would be measured. Treasury considered ways of integrating quantitative data into the MWM framework, and analysed information to select indicators based on qualitative data and quantitative measures. The policy advice identified risk and potential mitigation strategies. Treasury did not document decisions made to show linkages between data analyses and conclusions.

Policy intent

2.2 The APSC Delivering Great Policy Model states it is important to be ‘clear on intent’ to give an understanding of the problem and the intended outcome.33 The model states that being ‘clear on intent’ is:

- having a clearly defined problem;

- understanding the real reasons for the policy, not just those stated up-front;

- being able to articulate why government intervention is needed;

- being clear on the intended outcomes and how they’ll be measured; and

- having clarity on scope and timeframes.

2.3 In advice to government in May and August 2022, the key reasons given by Treasury for MWM was to construct a more complete picture of societal progress to enable government to better set and communicate policy priorities. Treasury articulated the rationale for having a national wellbeing framework as important to allow for better measuring the progress of all Australians beyond economic measures.

2.4 Budget Statement 4 of the October 2022–23 Federal Budget announced the planned release of a stand-alone MWM statement in 2023 and outlined the need for a wellbeing framework due to ‘limitations’ in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) framework; and stated that although the OECD framework enables international comparison of Australia’s progress, it is not ‘tailored to Australian circumstances’. The 2022–23 Federal Budget Statement 4 stated that a national wellbeing framework designed specifically for any particular country, is ideal for more accurate progress measurement.

2.5 Treasury identified the intended outcomes and how they would be measured to inform a more complete understanding of how well Australia as a country was doing, beyond purely economic measures. For example, Treasury considered what was previously in place, such as the former Measuring Australia’s Progress; and advising government in August 2022 that better wellbeing measurement would enable better government decision-making.

2.6 Treasury advised the Treasurer in December 2022 on options for the approach to developing a dashboard of indicators. The advice set the timeframe for the release of a stand-alone MWM statement by the end of July 2023 and an associated communication plan. The possible approaches for developing the dashboard of indicators included:

- linking to other government data initiatives;

- developing a new Treasury dashboard; or

- engaging the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) or the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) to develop and host the dashboard.

2.7 The advice did not include information on costings for other agency involvement. Treasury had consulted on costings with the ABS in August 2022 and the AIHW in September 2022.

Policy analysis

2.8 The Delivering Great Policy Model states that good policy is well informed by considering all quantitative and qualitative evidence.34 To develop a wellbeing framework capable of constructing a more complete picture of societal progress (see paragraph 2.3), Treasury met government and non-government bodies domestically and internationally; and ran two public submission rounds across October 2022 to May 2023 ‘to capture the diversity of what different parts of our community value’ (see paragraph 2.34). Treasury presented the stakeholders with the OECD Wellbeing Framework and sought feedback for how to contextualise it to Australia. Treasury also considered existing domestic frameworks and reports, such as the Report on Government Services, Closing the Gap, AIHW and the previous MAP as part of research to inform advice to government.35

2.9 Treasury analysed qualitative evidence extracted from the public submissions and meetings with government and non-government bodies domestically and internationally to determine themes, dimensions and indicators. The final list of indicators was selected after consultation with different government entities through an interdepartmental committee (IDC), based on what measures were practical and could be determined through existing quantifiable data sources.

2.10 Treasury did not record its own decision-making process to link feedback to adjustments made to the themes. There were examples from the public submission rounds that supported Treasury’s decisions to adjust the themes from those presented in the first round of public submissions (this is discussed further in paragraph 2.64).

2.11 There were six potential indicators raised through public submissions that were not incorporated in the first iteration (July 2023) of MWM. These potential indicators related to: suicide; oral health; spirituality; soil quality and water quality; food security; and Australia’s standing as a nation.36 Treasury was able to demonstrate it had considered and recorded reasons for excluding suicide, soil quality and water quality and food security. There were no records to show the reason for excluding the suggested indicators related to oral health and spirituality. Australia’s standing as a nation was discussed in the MWM statement.37

Consideration of other wellbeing frameworks

2.12 Treasury considered other options and solutions that could lead to the desired policy outcome of MWM. Before the release of MWM in July 2023, Treasury recorded meetings with 12 international organisations (non-governmental and governmental bodies) about wellbeing frameworks used in other jurisdictions. Treasury summarised the discussions from these meetings in advice to government and in a presentation for use to guide discussions with other stakeholders (e.g., state and territory governments). Treasury considered how these other wellbeing frameworks linked to Australian themes before the release of the MWM framework.

2.13 Treasury’s summary of its research into wellbeing frameworks overseas stated that the MWM team consulted with 14 international organisations. This included six public service agencies, seven non-government entities, including thinktanks and multinational bodies, and the Treasury India Post.38

2.14 The summary of Treasury’s research provided information on responsibilities and key dates for international wellbeing frameworks and identified key themes that emerged through the consultations. The document provided a summary of wellbeing framework approaches for a number of countries, set out against a range of criteria that showed an increasing impact on policy (see Appendix 5). Treasury did not use this work to identify a level of impact on policy for MWM.

Risk management

2.15 Section 16 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requires the accountable authority of an entity to establish and maintain systems and appropriate internal controls for the oversight and management of risk. The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy ‘sets out the principles and mandatory requirements for managing risk in undertaking the activities of government’; and requires risk management to be ‘embedded into the decision-making activities of an entity’, including in program and policy design and implementation.39

2.16 The Delivering Great Policy Model emphasises the importance of identifying key risks when developing policy advice.40 The Australian Government Guide to Policy Impact Analysis also highlights the importance of considering risk for policy delivery, to promote consistent management of risk when designing and implementing government initiatives. 41

Enterprise risk management

2.17 Treasury’s Enterprise Risk Management Framework and Policy (ERMFP), endorsed in July 2022, describes the expectations, principles and responsibilities for staff in applying effective risk management across all departmental activities. It sets out a model for encouraging a positive risk culture by ensuring that risk management activities are integrated into everyday activities and decision-making. A Risk Management Toolkit containing templates and guidance is available to officials to assist with assessing and managing risk.

2.18 The ERMFP emphasises the importance of reporting and maintaining records of risk information. Enterprise-level risk is managed and documented in a central risk register that is reviewed and updated twice a year. Risk reporting arrangements within the groups and divisions are determined by the relevant deputy secretary. Arrangements for program risk plans, registers, strategies and reporting risks are decided by the relevant senior responsible officer.

2.19 MWM was identified as an emerging risk in the Fiscal Group risk register in February 2023 and Treasury advised the ANAO in August 2024 that a decision was made to manage MWM risks at the Group level.

2.20 Consideration of risks and possible mitigation was recorded by Treasury in a draft stakeholder plan and in advice to government. Risks were not rated and there was no indication of risk appetite or tolerance recorded. Treasury advised the ANAO in October 2024 that ‘the identification and assessment of risk happened iteratively based on various drafts, discussions and email correspondence’.

2.21 Advice to government in August 2022 described three risks and sensitivities about not meeting stakeholder expectations and revealing data gaps. The mitigation detail was to be clear on intent and limitations in the October 2022–23 Federal Budget Statement 4.

2.22 Risks were identified for the consultation process in a draft consultation plan for the period March 2023 to May 2023. At least three of the ‘safeguards’ for these risks were stated to be application of clear public communication during the engagement process (see Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: Likely risks and safeguards described in draft consultation plan

|

Treasury likely risk |

Treasury safeguards |

|

Consultation fatigue |

Identify any synergies with other divisions working on related matters |

|

Avoid engagement methods that are difficult for stakeholders |

|

|

Major disagreement among stakeholders |

Clear documentation and evidence to support decisions. Recording and reporting on scope of consultation undertaken and high-level findings |

|

Short time period in which to consult on and deliver the Statement |

Planning engagement and using tools such as Converlensa to streamline the collection of feedback |

|

Some stakeholders would like to see the limited scope (based on OECD and using existing data) expanded. |

Clear communication on scope and limitations |

|

Some stakeholders may expect the Statement to be incorporated into upcoming Budget and policy processes |

|

|

Not all views can be incorporated in the final product |

|

Note a: Converlens is a system to enable collection and analysis of survey information.

Source: ANAO summary of Treasury documentation.

Did the design process consider practical implementation and policy evaluation?

Treasury researched and consulted on other wellbeing frameworks used globally, and tested indicators with other government entities to determine if indicators were practical to implement. The design process considered policy evaluation in relation to indicators. Treasury is considering how to embed the MWM framework into policy-making processes. There is no evaluation plan in place to measure the effectiveness of the MWM framework.

Considering practical implementation

2.23 The APSC’s Delivering Great Policy Model states that policies should be practical to implement; as such, the following elements should be considered at an early stage (before implementation)42:

- solution(s) that will lead to the desired policy outcomes;

- exploring and testing multiple options, and evaluating them with genuine input from implementers and end users;

- being clear that the policy can work in the real world;

- considering the long-term impacts, perverse incentives and unintended outcomes; and

- evaluation is ‘baked in’ from the outset, and linked to policy outcomes.

2.24 When seeking feedback from the public on the development of indicators for MWM, Treasury outlined in Budget Statement 4 of the October 2022–23 Federal Budget that:

according to the OECD and the internationally-accepted CIVITAS initiative43, indicators should be:

- relevant: indicators should be relevant to policy priorities;

- complete: indicators should adequately cover all policy priorities;

- measurable: indicators should have the potential for objective measurement;

- comparable: indicators should be defined and measured consistently, to enable comparisons within a country and internationally;

- reliable: preference should be given to indicators underpinned by objective and accurate data, which is not subject to different interpretations; and

- understandable: indicators should be unambiguous, easy to understand by decision-makers and key stakeholders, and be standardised where possible.

2.25 Treasury consulted through an IDC to determine which indicators were practical to implement. The list of indicators were sent to the ABS to review and make recommendations for improvement. Treasury requested the relevant government entities to assist with ‘peer review of analysis and data’ in July 2023. Treasury assessed each indicator and its data source to determine whether each indicator could be included in the MWM framework. This step was completed for every indicator except for overall life satisfaction. A visual representation of the final list of indicators and their data sources were compiled into an interactive dashboard and released as the MWM dashboard.

2.26 Treasury considered how the indicators would be evaluated post-release. To minimise changes to the dashboard and indicators, Treasury advised the Treasurer in June 2024 of conditions that must be met before changes to the indicator list can be made. One or more of these conditions must be met:

- the existing data source has been discontinued;

- a new data source has become available which better captures the indicator, is available more frequently or offers greater disaggregation; and

- a ministerial decision has been made.

Policy evaluation

2.27 There is no plan to evaluate whether MWM provides a more informed picture of social progress; or allows government to better set and communicate policy priorities. Treasury advised the ANAO in January 2025 that the MWM framework is evaluated ‘through annual updates of the dashboard, a three-yearly Statement, and arrangements in place to evaluate and strengthen the indicators’.

2.28 Treasury undertook consultation to ensure indicators could be linked to policy outcomes. For example, by including indicators which could be used in an evaluation. Treasury considered representation of progress against the themes and indicators. In the July 2023 version of the MWM dashboard, performance was indicated through a description: ‘improved’, ‘stable’ and ‘deteriorated’ to represent progress or otherwise for a particular indicator. This decision was made in line with feedback from the Productivity Commission. The July 2023 version of the MWM dashboard includes a paragraph under the heading ‘Progress’, to indicate how the indicator is showing improvement, stability or deterioration in a particular outcome.

2.29 Meeting records referenced ‘perverse incentives’ as a topic of discussion with the Wellbeing Commissioner from Wales. Treasury advised the ANAO in January 2025 that ‘perverse incentives arising from a measurement framework are minimal. The primary risk is that policymakers may focus solely on the indicators within the framework, overlooking other important factors that influence the policy in question’. Treasury further advised the ANAO in January 2025 that it intends to include consideration of unintended outcomes and evaluation in its implementation strategy, which is being developed (see paragraph 3.4).

2.30 Treasury considered the long-term effects of the policy by embedding consideration of future Australians’ wellbeing in a question within its stakeholder consultation. Treasury summarised key points from the submissions, including identifying that there was a need to ‘clarify the long-term MWM objectives and links to decision-making processes’. Advice to government in August 2022 stated that if MWM was ‘carefully designed, there may be potential to inform and improve policy design and evaluation more broadly across the Australian Government’. The longer-term options were provided in advice to government in July 2023 (see paragraph 3.2).

Was adequate stakeholder consultation undertaken?

Before the release of MWM in July 2023, Treasury consulted with stakeholders to design the themes, dimensions and indicators. The consultation consisted of meetings with government and non-government bodies domestically and internationally; and two public submission rounds. Treasury provided public updates throughout the consultation process. Treasury received feedback from the public wanting more time for consultations. Treasury did not document the rationale for how themes and indicators were selected based on the consultation feedback.

Practical stakeholder engagement

2.31 The Australian Public Service (APS) Framework for Engagement and Participation sets out how Commonwealth entities can ‘engage effectively with citizens, community and business’. It includes 10 standards to apply in engaging with stakeholders, as set out in Box 2.

|

Box 2: Ten standards for engaging with stakeholders |

|

2.32 The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) guide, Getting stakeholder engagement right, also outlines that ‘successful stakeholder engagement involves adapting your approach for each stakeholder’ to:

- identify and map out stakeholders to develop an engagement plan;

- execute the engagement plan in a considered and transparent way; and

- close the feedback loop by informing stakeholders about how their feedback has been incorporated.

2.33 See Table 2.2 for ANAO’s assessment of Treasury’s stakeholder engagement against the elements of the APS Framework for Engagement and Participation. Treasury’s stakeholder engagement is discussed in detail following Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Summary of ANAO’s assessment of Treasury’s stakeholder engagement against the APS Framework for Engagement and Participation

|

Stakeholder type |

Elements of stakeholder engagement (see Box 2) |

|||||||||

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

Public submissions |

● |

● |

◑ |

● |

◕ |

◕ |

◕ |

◑ |

● |

◑ |

|

Other stakeholder meetings |

● |

● |

● |

● |

◕ |

◕ |

● |

● |

● |

◕ |

|

Overall |

● |

● |

◕ |

● |

◕ |

◕ |

◕ |

◕ |

● |

◕ |

Key:

◯ No evidence of relevant activity (i.e. planning, implementation and closure).

◔ Significant issues identified, with evidence of major impact on the overall contribution of stakeholder engagement to MWM.

◑ Issues identified, with some impact on the overall contribution of stakeholder engagement to MWM.

◕ Issues identified, but these have not substantially undermined the overall contribution of stakeholder engagement to MWM.

● Activities are consistent with best practice.

Source: ANAO analysis.

Consultation process

2.34 The MWM statement states that the MWM framework was developed ‘through extensive research and consultation’ and describes a consultation process which included the public submissions and the meetings with other countries and international organisations.44 The MWM statement said:

Overall, submissions and stakeholder consultations supported the introduction of MWM and the prospect of a role for the Government in monitoring and advancing progress across a broad range of wellbeing indicators. The submissions emphasised the importance of including the experiences of different groups – such as women, First Nations people, veterans, people with disability, and age cohorts – and different geographic locations, across all themes.45

2.35 Treasury’s consultation process ran from October 2022 to May 2023 and consisted of:

- seventy-one meetings with various groups;

- one public submission round between October 2022 and January 202346; and

- a second public submission round between 14 April 2023 and 26 May 2023.47

2.36 Treasury reported it received 165 submissions in the first public submission round and ‘around 120’ submissions in the second round. The MWM statement included statistics on consultation in a diagram which included all stakeholders consulted, both through the public submission rounds and the meetings with government and non-government bodies domestically and internationally.

2.37 The MWM statement says the consultations identified areas across all the wellbeing themes where there were opportunities to improve the measurements through improving data quality by:

- considering the averaging effect of national statistics; and

- disaggregation of data to better identify variances, including regional variance.48

2.38 The MWM statement identified opportunities to improve measurements across the themes with a statement that ‘the Government will consider these suggestions, along with other consultation responses to this Framework, as it looks at how to ensure Australia’s data system provides the most valuable means to measure indicators across this and other frameworks’.49 This is reproduced and summarised in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: MWM statement: opportunities to improve measurements across five themes

|

Theme |

Potential improvement for measures identified through the consultation process |

|

Healthy |

|

|

Secure |

|

|

Sustainable |

|

|

Cohesive |

|

|

Prosperous |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of Treasury documentation.

2.39 In the second public submission round, Treasury asked whether the themes resonated with stakeholders. Treasury received 117 submissions in the second public submission round. Of these, Treasury received 71 responses to the question asking if the themes resonated. Table 2.4 shows 54 respondents agreed that the themes resonated with them (76 per cent).

Table 2.4: Number of responses to the optional question about whether the themes resonated

|

Response |

Number of responses to the question |

Percentage response (%) |

|

Yes |

54 |

76 |

|

No |

17 |

24 |

|

Total |

71a |

100 |

Note a: There were 71 responses to the optional question out of 117 submissions. The remaining 46 submissions did not respond to the optional question on themes.

Source: ANAO analysis of Treasury documentation.

2.40 The remaining 17 respondents to the questions on themes said the themes did not resonate with them. Reasons given were:

- wanting a stronger emphasis on the environment;

- disagreement with applying a hierarchy to the themes;

- concern about the consultation process (including wanting more input into indicators);

- disagreement with the emphasis on sustained economic growth; and

- concern about a lack of specific reference to certain topics (like housing; access to services; education; gender; and aged care).

The approach to stakeholder engagement

2.41 The APS Framework for Engagement and Participation recommends having a definition of the objective and choosing the right approach (see Box 2). The APSC guidance, Getting stakeholder engagement right, advises that engagement with stakeholders to gain buy-in and access expertise will be more successful if there is a plan in place for stakeholder engagement at the outset. The guidance provides some templates and advises that the plan should include:

- identifying and mapping stakeholders based on interest and influence on taskforce objectives;

- defining the issues for stakeholder input and developing strategies for engagement;

- having a system for recording and incorporating stakeholder feedback and providing updates to stakeholders on consultation findings; and

- evaluating and making adjustments to stakeholder engagement method as you go along to ensure it is effective.50

2.42 Treasury’s approach for consultation was contained in a communication strategy dated August 2022, detailed in advice to the Treasurer in December 2022, and a draft consultation plan from February 2023. The communication strategy created in August 2022 covered the consultation process, including public submission rounds. Treasury advised the ANAO in February 2025 that the communication strategy and its timeframes were superseded by other arrangements detailed in advice to the Treasurer in December 2022.

2.43 Treasury advised government in August 2022 of its plans to carry out consultation by speaking with experts as well as carrying out public submission rounds. Advice to the Treasurer in March 2023 also provided information on a consultation pack that detailed Treasury’s approach to the second public submission round. Treasury provided advice to the Treasurer in October 2023 about consultation approaches for taking the work forward including the option of a National Conversation. This option was not pursued as Treasury advised that it ‘can be pursued at a later date when MWM is more mature’.

2.44 A draft consultation plan was created in February 2023 (labelled March to May 202351), before the second round of public submissions. The draft consultation plan states its purpose is to:

outline Treasury’s strategy for engaging with internal and external stakeholders critical to the success of the Measuring What Matters statement.

2.45 The draft plan states that the outcome of the plan was to ‘consult more broadly to build public support … test whether values resonate … [and] whether gaps remain’. Treasury advised the ANAO in August 2024 that the public submission rounds were not included in the draft plan. Treasury further advised the ANAO in January 2025 it became apparent a second public submission round would be necessary after review of the initial round. A consultation pack was provided to the Treasurer in March 2023 to approve for the second public submission round. The Treasurer did not approve the consultation pack as the Treasurer’s Office advised in March 2023 that ‘it has been overtaken by events and will not be formally signed.

2.46 The draft consultation plan from February 2023, described five different approaches to consultation:

- expert consultation, consisting of one-off ‘small, virtual, theme based, round tables’;

- three official-level expert reference group meetings, to separately cover indicators, values and statement drafts;

- regular meetings of a small Treasury internal reference group;

- one-off, virtual meetings with international bodies; and

- inter-departmental committees (IDCs) and ongoing engagement with agencies.

2.47 Public engagement with groups, such as those who had made submissions during the consultation process was not included as an element in the draft consultation plan.

Stakeholder meetings

2.48 The APS Framework for Engagement and Participation recommends the consideration of the right participants for consultation (see Box 2). In addition to the two public submission rounds, Treasury met stakeholders to discuss MWM. The MWM statement states that the MWM framework has been based on ‘public consultations and the findings of other national and international wellbeing frameworks’.

2.49 The draft consultation plan (February 2023) identified non-government organisations to engage as part of community consultation. These were ‘possible invitees’ identified ‘through direct approaches to the MWM team and consultation with Treasury Divisions and Commonwealth agencies’. Treasury advised the ANAO in January 2025 that ‘the draft consultation plan was intended as a guide, rather than a definitive plan that had to be followed rigidly, regardless of changing circumstances. For instance, the proposed roundtables outlined in the draft consultation plan were replaced by the decision to hold a second round of public consultation’.

2.50 In the draft consultation plan (February 2023), Treasury identified 115 non-government organisations as ‘possible invitees’ for consultation, listed against the five MWM themes.52 Treasury had meetings with five of these organisations. Four out of the five also made a submission through the public consultation process. Out of the remaining 110 organisations, 53 made a written submission (48 per cent). Out of the 16 non-governmental ‘expert’ organisations that Treasury met, three were identified previously on the draft consultation plan (all made submissions); and an additional three organisations that met with Treasury also made written submissions.53

2.51 The APSC provides templates to guide stakeholder engagement and recommends using an influence and impact score. Treasury did not the weigh the influence or impact of stakeholders on the consultation process before the release of MWM.54

2.52 Treasury reported it had ‘more than 65 meetings’ throughout October 2022 to May 2023.55 The stakeholders were a mix of Commonwealth, state and territory government officials, stakeholders from the public and industry, some of whom had also made written submissions; and organisations from other jurisdictions. In August 2024, Treasury advised the ANAO that these meetings had been influential in the design of MWM.

2.53 Summaries of 119 meetings (71 held before the closure of the second round of stakeholder submissions and 48 from after the end of the second round of stakeholder submissions) were recorded by Treasury. The records included the meeting purpose, issues discussed and a link to notes. The draft consultation plan stated that all meeting notes would be completed after the various engagement activities.

2.54 The number of times information was recorded against the ‘meeting purpose’, ‘issues discussed’ and ‘link to meeting notes’ is shown in Table 2.5. Treasury advised the ANAO in January 2025 that if a meeting had meeting notes, it considered the meeting to be material. Treasury advised that the 71 meetings with stakeholders before release of MWM were influential in its design (see paragraph 2.52). Treasury did not include links to meeting records for all 71 meetings (see Table 2.5).

Table 2.5: Number of times and percentage of meeting information recorded by Treasury

|

Meeting record fields |

Number of times information was recorded |

Percentage of fields completed (%) |

|

Meeting purpose |

38 |

53 |

|

Issues discussed |

62 |

87 |

|

Link to meeting notes |

32 |

45 |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Communication with stakeholders

2.55 The APS Framework for Engagement and Participation includes elements to: manage expectations; promote transparency and sufficiency of information; provide fair representation of all views; and close the loop (see Box 2). The APSC guidance on stakeholder engagement discusses ‘closing the loop’56 and includes guidance to inform stakeholders (even midway) on how their contribution has affected the policy development.57

2.56 The draft consultation plan identified three risks that could be mitigated by ‘clear communication’ (see Table 2.1). To communicate the purpose, the first public submission round invited feedback on ‘measuring what matters’ and provided guidance that proposed indicators should be ‘relevant, complete, measurable, comparable, reliable and understandable’. A consultation pack was developed for the second public submission round (April 2023 to May 2023).58 Treasury provided an update to the public on the consultation process through this consultation pack.59

2.57 The July 2023 MWM statement provided public information on the consultation process and included statistics on the number of public submissions categorised by stakeholder groups.60

Arrangements to identify and engage with relevant stakeholders

2.58 The APS Framework for Engagement and Participation expects entities to be inclusive and allow diverse voices to be heard (see Box 2) and provides guidance on how to effectively engage with citizens, the community and business.61 The framework describes three principles for engagement and participation: listen; be genuine; and be open.62 The framework states that ‘aspiring to the principles will help ensure engagements go beyond seeking buy-in and instead tap the public’s expertise and lead to better policy, programs and services’.63

2.59 The APSC states:

It’s important to genuinely engage with stakeholders with an interest in your taskforce, such as line areas or agencies or state and territory governments, as well industry groups, peak bodies and users of products or services, in order to inform your work, gain new ideas and ensure you provide evidence-based advice.

You should identify and engage with stakeholders early on and set aside time to maintain relationships, including through updates on taskforce work and closing the feedback loop. Effective stakeholder engagement can help with valuable buy-in to your taskforce’s objectives.64

2.60 Treasury provided the opportunity for a diverse range of stakeholders to submit views for MWM, through its two public submission rounds. Treasury identified stakeholder consultation for MWM as important because broader consultation would improve the likelihood that MWM was reflective of a diverse set of views; and the community was recognised as best-placed to advise on issues of most importance to it in an Australian context.65 The first release of the MWM statement highlighted the importance of the MWM framework being informed by public consultation by asserting a government commitment to ‘properly take account of changing public perspectives’, to allow for refinement of the MWM framework over time.66 The MWM statement said that the Government ‘has listened to the views of a broad range of people to capture the diversity of what different parts of our community values’.67

Addressing stakeholder feedback

2.61 The APS Framework for Engagement and Participation expects continuous improvement to be made following feedback (see Box 2). Treasury used the public consultation process as a source of evidence to feed into the design process. Treasury did not document decisions made to support the changes to the themes and indicators. The ANAO observed changes made to the MWM framework from the initial stakeholder consultation phase through to the release of MWM in July 2023.

2.62 Poor information management introduces the risk of not being able to find information when needed. This can negatively affect the trust in the completeness and accuracy of the information that is stored. Business activities and key decisions should be documented in accordance with government record keeping requirements and an entity’s own information governance policy and framework.

Opportunity for improvement

2.63 Treasury could consider improving how business information is created and retained to demonstrate the basis on which key policy design and implementation decisions were taken.

2.64 During the first public submission round, Treasury presented the OECD framework as a base and sought further feedback about how this could be adjusted for the Australian context. During the second round open for public submissions, Treasury presented a set of five themes with ‘draft descriptions’ for consideration.

- Prosperous: a growing, productive and resilient economy.

- Inclusive: a society that shares opportunities and enables people to fully participate.

- Sustainable: a natural environment that is valued and sustainably managed in the face of a changing climate for current and future generations.

- Cohesive: a safe and cohesive society that celebrates culture and encourages participation.

- Healthy: a society in which people feel well and are in good physical and mental health, now and into the future.68

2.65 The MWM framework was released with Secure as a new theme, amendments to the Prosperous and Healthy theme, and inclusion, fairness and equity described as ‘cross-cutting dimensions’.

- Healthy: A society in which people feel well and are in good physical and mental health, can access services when they need, and have the information they require to take action to improve their health.

- Secure: A society where people live peacefully, feel safe, have financial security and access to housing.

- Sustainable: A society that sustainably uses natural and financial resources, protects and repairs the environment and builds resilience to combat challenges.

- Cohesive: A society that supports connections with family, friends and the community, values diversity, and promotes belonging and culture.

- Prosperous: A society that has a dynamic, strong economy, invests in people’s skills and education, and provides broad opportunities for employment and well-paid, secure jobs.69

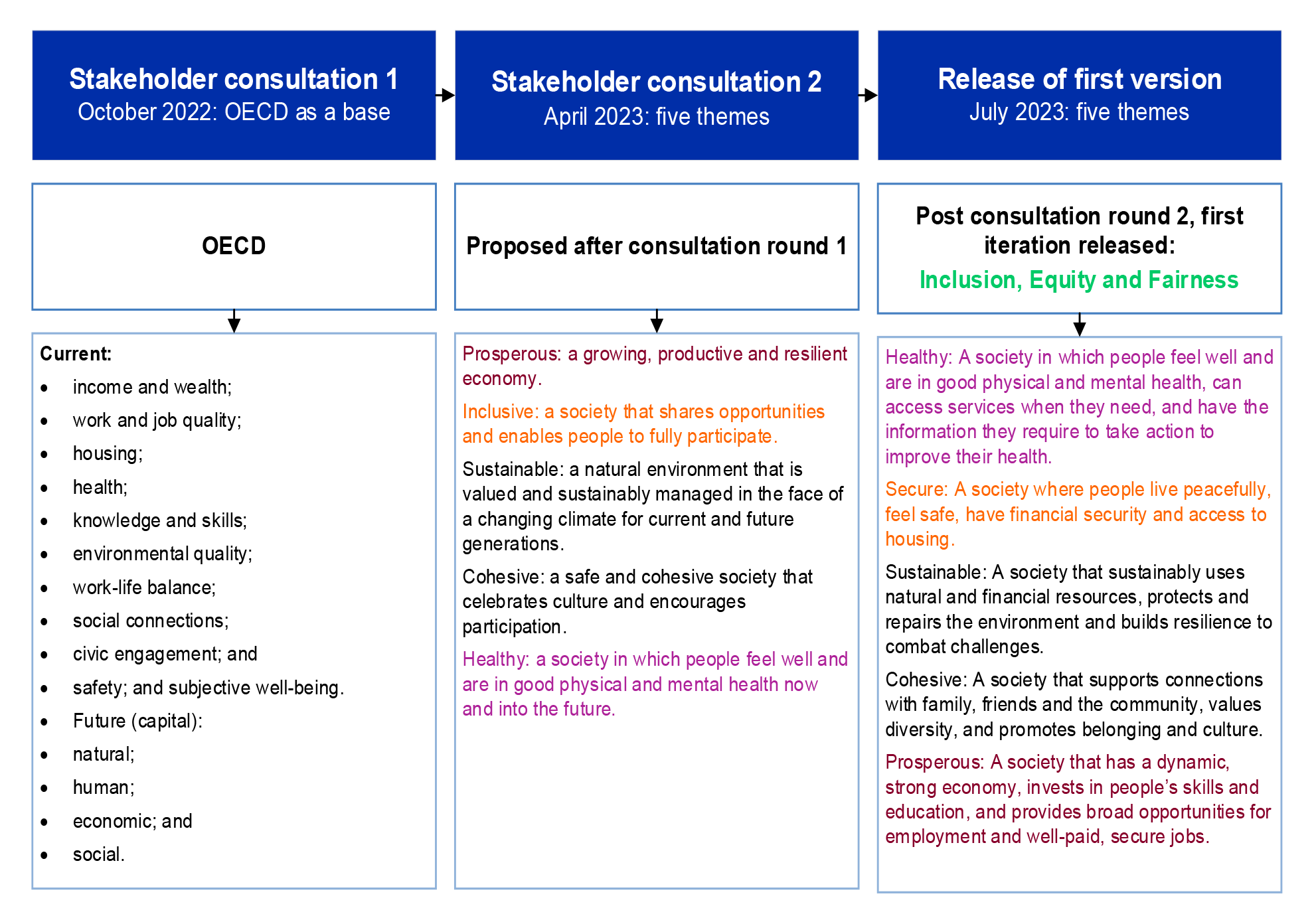

2.66 Figure 2.1 shows the timeline of consultation against the changes made to the MWM framework.

Figure 2.1: Timeline of consultation against MWM framework adjustments

Key:

Red indicates change in order of Prosperous theme made between April and July 2023.

Purple indicates change in order of Healthy theme made between April and July 2023.

Orange indicates change in order of Inclusive theme and insertion of Secure theme between March and July 2023.

Green indicates the addition of ‘Inclusion, Equity and Fairness’ as cross-cutting dimensions that encompass the five themes.

Source: ANAO analysis of Treasury documentation.

2.67 The draft consultation plan identified the risk of a short period of time to consult on the statement, which could be mitigated by planning engagement and using tools like Converlens to help streamline feedback (see Table 2.1).70 Treasury used Converlens during the second public submission round. Not all participants used the Converlens form and instead referred to a separate set of questions also provided in the consultation pack under ‘what do we need to know’; or participants did not respond directly to either the Converlens form or questions provided in the consultation pack. Table 2.4 shows the number of responses to the question about whether the themes resonated.

2.68 There was an inconsistency in the consultation pack information that might impact on clarity of communication for stakeholders. For example, the Converlens form included a specific question asking stakeholders for possible indicators and did not highlight the criteria for indicators identified in round one. The consultation pack also stated that ‘further feedback on, and suggestions for, indicators is welcomed, particularly in response to the themes’.71 In January 2025, Treasury advised the ANAO that the second public round was not intended to be used to identify indicators and was to focus on themes.

Opportunity for improvement

2.69 Treasury could consider improving consistency of communication about consultation processes.

2.70 The feedback from the second public submission round included feedback that indicated support for longer than the six week consultation period provided.72 Treasury acknowledged this issue internally in the conclusions it made about the second round of consultation.

2.71 When involving stakeholders to seek ideas, Treasury’s stakeholder consultation principles recommend a 10 to 16 week timeframe. Treasury had not used the department’s guidance to select the timeframes. Treasury advised the ANAO in January 2025 that the purpose of the second round of public submissions ‘more closely aligns with checking direction, which has a recommended timeframe of 6 to 10 weeks in the Treasury Stakeholder consultation principles’.

3. Planning for implementation

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) has effective arrangements to support the implementation of Measuring What Matters (MWM).

Conclusion

Treasury had largely effective arrangements in place to support the implementation activities for embedding MWM. Treasury facilitates discussions on MWM across government through an interdepartmental committee. Treasury has made progress to embed MWM into policy design and consulted with the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) to improve the data quality. There are no arrangements in place to monitor, report or evaluate whether MWM is achieving its intended policy objective. The second MWM statement is intended to be released in 2026. Treasury does not have arrangements in place to facilitate the publication of the next MWM statement.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at: establishing arrangements to monitor and evaluate MWM; and for the publication of the next MWM statement.

3.1 The Australian Public Service Commission’s (APSC) APS Craft and APS Mobility Framework outlines key capabilities for designing, developing and implementing government initiatives by establishing:

- arrangements to oversee implementation progress, coordination of responsibilities and assist with achieving the desired policy outcomes73; and

- monitoring and evaluation arrangements to regularly review and test that outcomes are on track to be achieved.74

3.2 The Australian Government has stated that MWM is ‘an important foundation on which we can build — to understand, measure and improve on the things that matter to Australians’.75 Treasury has policy responsibility for the MWM framework and is leading the implementation of the MWM framework across government. Treasury provided advice to government in July 2023 on activities to integrate MWM into policy design. This includes working with the ABS to improve data timeliness and disaggregation and embedding the framework into policy design across government through the following activities agreed to by government:

- developing guidance for government departments to inform policy-making;

- engaging with the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) and APS Reform Office and the Australian Centre for Evaluation (ACE); and

- sharing best practice on developing and implementing wellbeing frameworks with states and territories.

Were governance arrangements established to manage implementation?

Treasury established an interdepartmental committee to facilitate discussions and seek feedback on MWM across government. Treasury worked with the ABS to provide advice to government and received funding for the ABS to reinstate and expand the General Social Survey as a dedicated survey for MWM. Treasury has made progress to embed MWM into policy design across government.

Oversight arrangements

3.3 The Social Policy Division (SPD) within Treasury’s Fiscal Group is responsible for the operational management of MWM. The SPD Business Plan 2024 outlines one of its roles is to ‘partner with others to deliver the Government’s social policy priorities, including gender equality, Targeting Entrenched Disadvantaged and Measuring What Matters’.76

3.4 Treasury created a draft project plan in October 2024 for the approach to develop the ‘implementation strategy’ for embedding MWM, to provide to government in 2025. The draft project plan stated that MWM would have line management and standard reporting arrangements.

Interdepartmental committee

3.5 Treasury used an interdepartmental committee (IDC) to facilitate discussions, share development ideas and seek feedback on MWM. There were two iterations of the IDC that operated across the design and implementation of MWM.

3.6 The first iteration of the IDC operated during the development of MWM as a mechanism to engage across the APS and improve ‘understanding of existing or planned wellbeing resources and avoid missing or duplicating relevant work’.

3.7 After the release of MWM in July 2023, the IDC re-convened with members from the first iteration to discuss the next steps for MWM and gather feedback from members. IDC terms of reference for MWM were established in October 2023 with the same members as the IDC that operated during design and development (see Appendix 6 for the IDC members list). The IDC terms of reference defined the purpose and scope of this iteration of the IDC, which was to:

- provide a forum for Treasury to keep Commonwealth entities updated on the MWM workplan; and

- seek feedback and advice on MWM work, such as guidance to agencies about how to use the MWM framework for policy design, and the indicator and data improvement plan.

3.8 Additionally, the IDC terms of reference stated the IDC would convene every three months, with the first meeting taking place in December 2023 (see paragraph 3.27).

Operational risk management

3.9 Section 16 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requires the accountable authority of an entity to establish and maintain systems and appropriate internal controls for the oversight and management of risk. The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy ‘sets out the principles and mandatory requirements for managing risk in undertaking the activities of government’ and requires risk management to be ‘embedded into the decision-making activities of an entity’, including in program and policy design and implementation.77

3.10 Treasury documented risks to MWM in briefs, planning documents, a workplan and submissions to the Treasurer. In August 2024, Treasury established a risk register to document project risks associated with MWM, including risks to implementation and risks to the dashboard update. The risk register contains details on:

- risk events;

- control assessments;

- risk ratings;

- proposed management action;

- risk tolerance;

- risk treatment;

- responsible officers; and

- residual risk ratings.

3.11 Treasury advised the ANAO in August 2024 that the risk register is reviewed by the MWM team on a fortnightly basis and updated accordingly.

Shared risk

3.12 Element Six of the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy states the management of shared risk requires ongoing communication between entities to accept and effectively manage them. Depending on the context of the work, entities can do this informally (discussions and considerations) or formally (risk assessments, risk frameworks and risk registers).

3.13 Treasury advised the ANAO in November 2024 that it had aimed to minimise the risk of data not being available by selecting ‘publicly available data and data from government entities. Permission for use was requested from all data custodians and was one of the criteria included in the checklists’.

3.14 Responsibility for managing and providing an annual data update to the MWM dashboard was transferred to the ABS in April 2024 (see paragraph 3.20). Treasury assisted the ABS with the delivery of the data update for the 2024 MWM dashboard and the transfer of responsibility of the dashboard to the ABS. The ABS’s Project Plan for the MWM dashboard update states there will be weekly meetings with Treasury to ‘keep Treasury informed of dashboard timelines, risks and issues’.

3.15 Treasury created a risk register to outline the risks and issues to the data update and the collaboration with the ABS. The risk register contained seven risks, two of which were co-owned between the ABS and Treasury. These were:

- data timeliness; and

- data retrieval from data custodians.

3.16 The ABS maintained its own risk register for the delivery of the 2024 MWM dashboard update. The two risk registers were inconsistent. The two co-owned risks identified by Treasury were not present in the ABS register. A new shared risk register was established in November 2024 between the ABS and Treasury to manage risks for the 2025 MWM dashboard update.

3.17 A memorandum of understanding (MoU) between the ABS and Treasury was established in February 2025 to formally set roles and responsibilities on work relating to the 2025 MWM dashboard. The MoU assigns the ABS the responsibility to work ‘with non-ABS data custodians to access and understand their data, present it accurately, and describe its quality’. Treasury’s role is to support the ‘ABS to acquire non-ABS data (if needed)’. The shared risk register was updated in February 2025 to account for the treatment of the shared risk with data custodians, which involves the ABS to ‘identify bottlenecks and address any issues related to lead times’ and provide updates to Treasury on emerging concerns.

Data improvements

3.18 Leading up to the advice that was provided to the Treasurer in October 2023 on the next steps for MWM, Treasury engaged with the ABS to address data gaps and discuss the possibility of transitioning to a hybrid model.78

3.19 Treasury advised the Treasurer in October 2023 that the public reception towards the release of the MWM framework was ‘overall positive’ and identified the main criticisms related to data gaps and data timeliness. To address criticisms from the public about the timeliness of the data and improve the data for future updates to the dashboard, Treasury advised the Treasurer to seek authority for a budget proposal to address data gaps. The advice provided detail on the potential reinstatement of the General Social Survey (GSS), as results from the GSS were a key input into the MWM framework’s dashboard of wellbeing indicators. The Treasurer agreed for Treasury to explore options for how to improve the data timeliness issue.

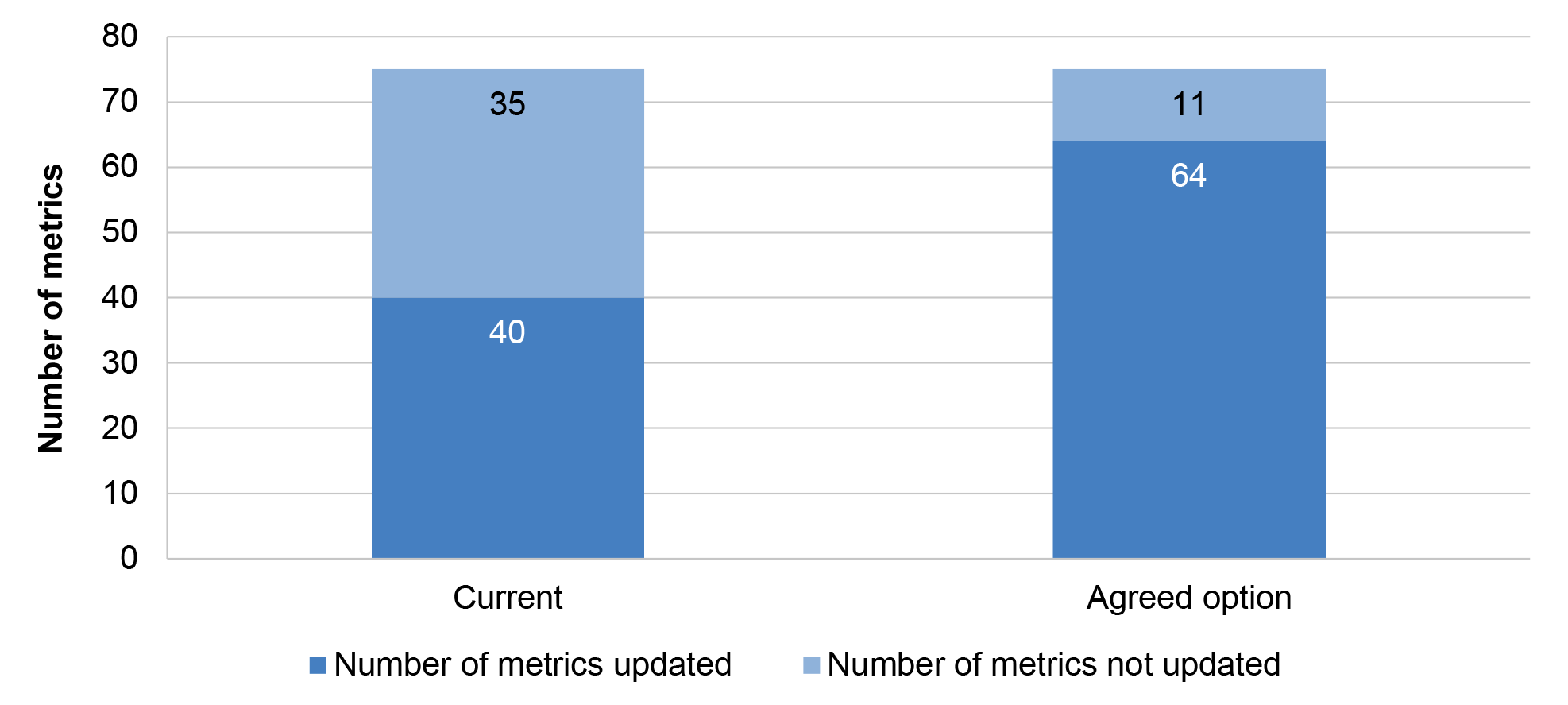

3.20 In January 2024, advice was provided to the Treasurer to outline options to address the data limitations. Treasury determined within the January 2024 data arrangements, the next annual data update would refresh 40 out of the 75 wellbeing metrics that sit behind the 50 MWM indicators (see Appendix 3 for the full list of wellbeing metrics).79 The Treasurer agreed to pursue the option to reinstate and redesign the GSS to allow for better data disaggregation and improvements. Treasury also outlined in its advice the possibility of transferring responsibility of the MWM dashboard to the ABS and that additional details would be outlined in advice from the ABS. Figure 3.1 shows the increase in the number of wellbeing metrics updated annually under the agreed option. The ABS was sent the options in December 2023.

Figure 3.1: Number of metrics updated annually — January 2024 against the agreed changes

Source: ANAO analysis of Treasury documentation.

3.21 Treasury provided advice to government in April 2024 on investing $57.9 million in the ABS to continue to modernise systems and operations. Of the $57.9 million, $14.8 million was to be invested in MWM data over five years, starting from 2023–24, through the reinstatement and expansion of the GSS as a dedicated wellbeing survey.

3.22 Treasury also sought to embed the delivery of the data and dashboard in the ABS to maximise existing expertise and infrastructure and reduce duplication. Transferring the management of the data delivery and dashboard update to the ABS was approved by government in April 2024. Treasury received approval in April 2024 to develop and present in 2025 a strategy to embed the MWM framework into policy design across government.

Measuring What Matters 2024 dashboard update

3.23 Management of the MWM dashboard and responsibility for annually updating the data was transferred to the ABS in April 2024. Treasury’s role is to provide guidance where changes to indicators were needed and to support the ABS to implement and describe the MWM framework. Treasury and the ABS held weekly meetings from June 2024 through to August 2024. To release the 2024 MWM dashboard in August 2024, the ABS satisfied its data requirements to ensure appropriate assurance over the data. The ABS clearance report stated all pages were reviewed by the relevant executive level staff at Treasury.

Embedding Measuring What Matters

3.24 The advice to the Treasurer in October 2023 outlined the next steps for MWM, which included improving the data for future data updates and key activities to progress the decisions agreed by government (see paragraph 3.2). The key activities were to take place ‘in the next 12 months’ and involved:

- influencing the budget process through advice in the Budget Process Operational Rules (BPORs) and developing wellbeing guidelines for departments to inform policy development (see paragraph 3.26);

- engaging with the Australian Public Service Commission, APS Reform Office and the Australian Centre for Evaluation (ACE) to embed the framework in ‘existing capability building efforts’ (see paragraph 3.29);

- sharing best practice on developing and implementing wellbeing frameworks with states and territories (see paragraph 3.35); and

- refining the MWM framework based on community feedback and continued international engagement.

3.25 The key deliverables and timeframes for each activity were described in a resource planner created in October 2023. The timeframes set out in the planner were not met. Treasury was advised by the Treasurer’s Office in December 2023 to focus on progressing work to address the issues relating to data gaps and data timeliness (see paragraph 3.19). This deliverable was separate from what was agreed by government.

Developing guidance for departments

3.26 In August 2023, Treasury and the Department of Finance completed a review of the BPORs, in advance of the 2024–25 Federal Budget. Wording for MWM guidelines was submitted for inclusion into the BPORs, to provide guidance for how to consider the MWM framework in policy development. This was agreed to by government in October 2023.

3.27 Treasury developed a draft wellbeing policy guide for agencies to reference when considering the BPORs guideline for MWM in their policy development. Treasury convened with IDC members in December 2023 to circulate the draft wellbeing policy guidance for feedback and sought advice on how to address data gaps.