Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Performance Statements of Major Australian Government Entities — Outcomes from the 2024–25 Audit Program

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Executive summary

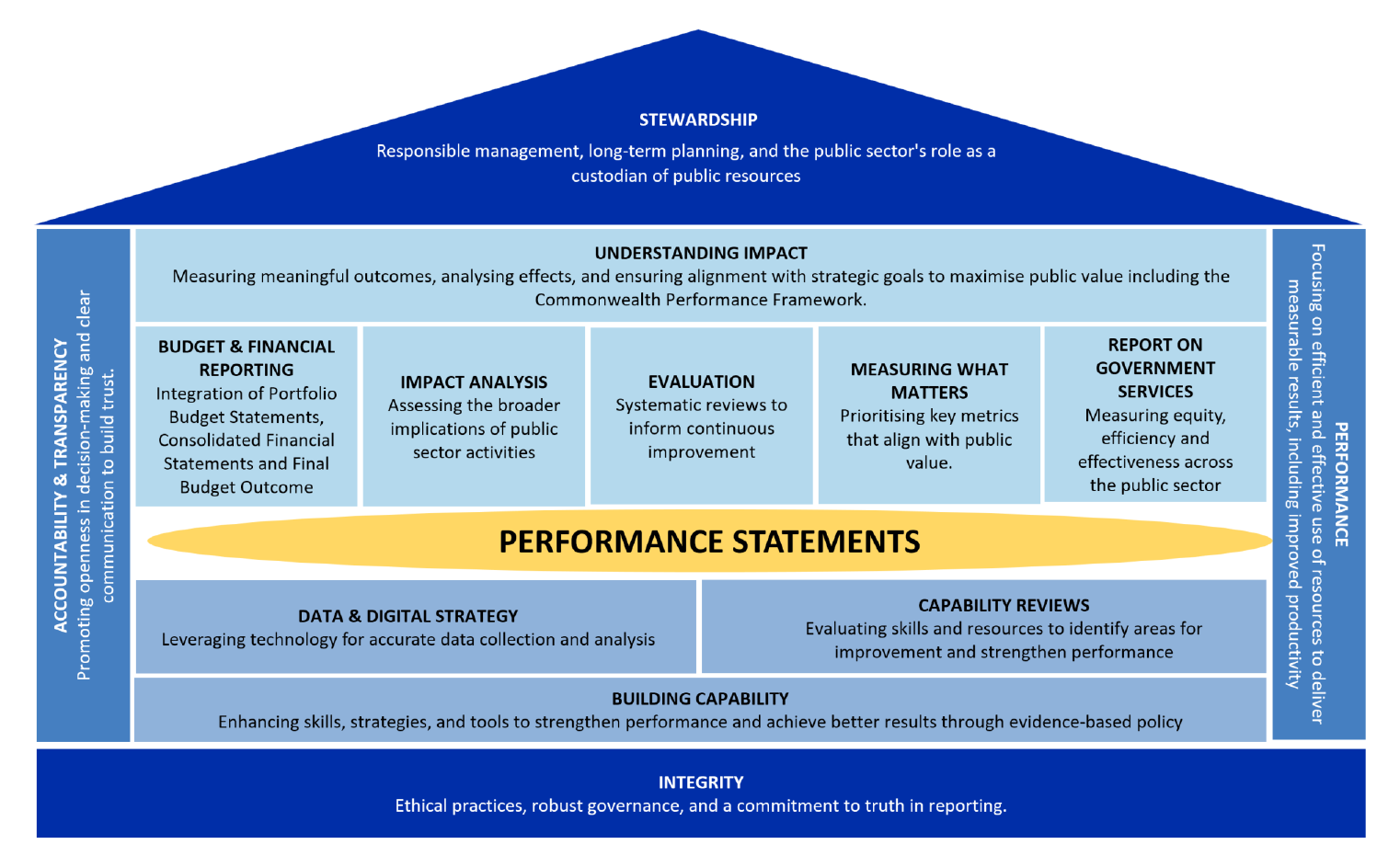

1. Parliament requires clear and transparent information about how Commonwealth entities are performing and whether public resources are being used properly1 for the purposes intended. By having access to appropriate and meaningful performance information, Parliament can better hold government and entities accountable for their performance. This in turn helps to ensure government policies, programs and services are achieving their intended outcomes and delivering value to the public.

2. The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requires Commonwealth entities to provide meaningful information to the Parliament and the public.2 It imposes specific obligations and requirements for entity performance reporting, through the preparation of annual performance statements.3 It also makes provision for annual performance statements to be examined by the Auditor-General, at the request of the Minister for Finance or the responsible minister.4

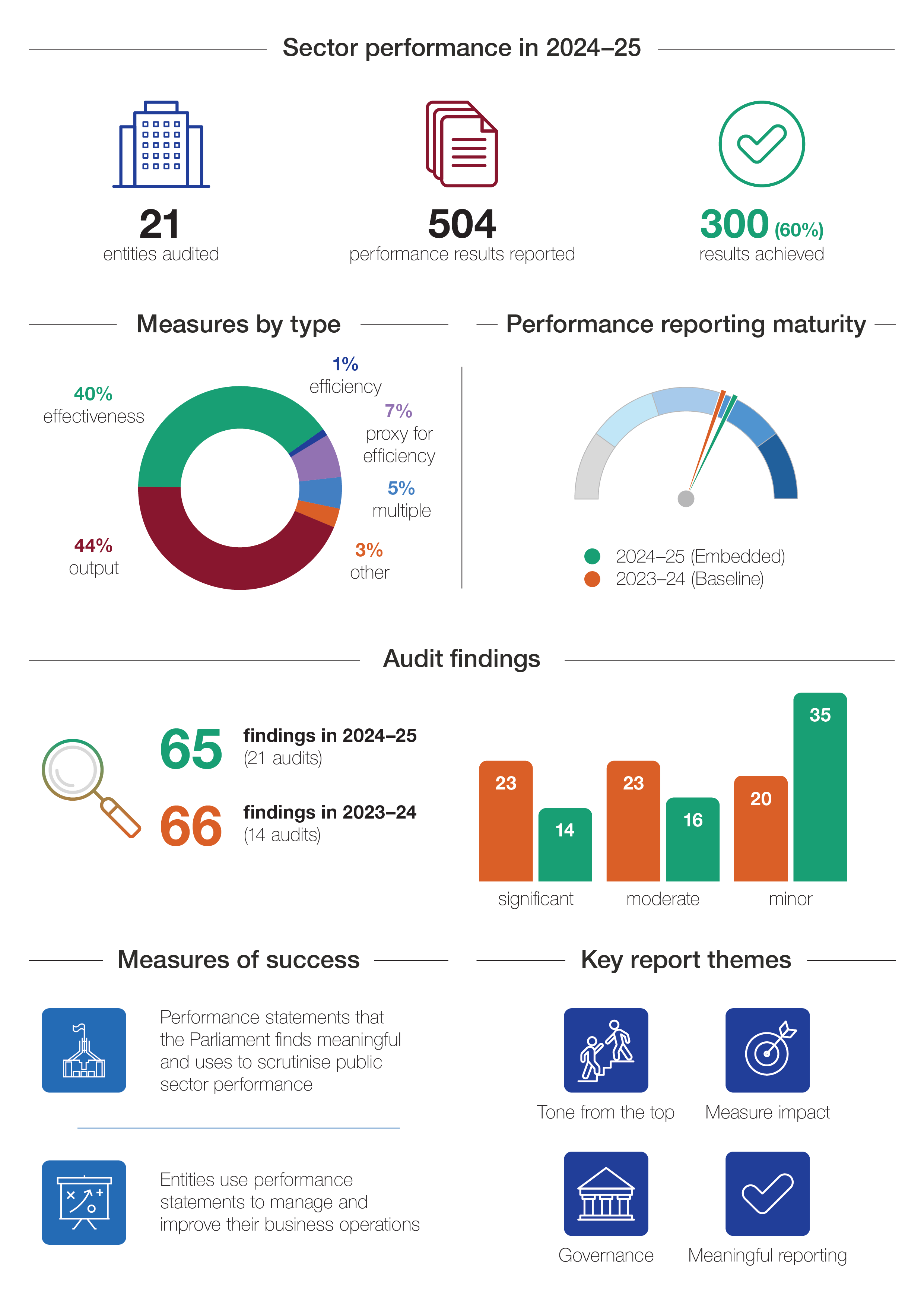

3. For the year ended 30 June 2025, the ANAO audited the performance statements of 21 entities. These include all the Departments of State, the largest department of the Parliament, the Australian Taxation Office, the National Disability Insurance Agency, the National Indigenous Australians Agency, and Services Australia.

4. The audited population is substantial in terms of accountability to Parliament, expenditure and revenue, and the functions of the Australian Government. Collectively, the 21 audited entities were responsible for $868 billion in revenue and $858 billion in expenditure in 2024–25 — over 85 per cent of all revenue and expenditure presented in public sector entities’ financial statements.

5. Auditing of annual performance statements by the ANAO provides independent assurance to the Parliament and the public that the information presented is accurate, reliable and appropriate for accountability and democratic oversight.

6. Preparing and using performance information reflects sound business management practice. It is therefore concerning when entities indicate that the performance measures reported in their annual performance statements are not useful for managing the business or have been developed specifically for inclusion in the performance statements. While it is not necessary for performance measures used for external accountability and internal management to be the same, there should be a logical linkage between them. By way of comparison, there would be little confidence in an entity that said it did not use the financial information it reported externally to manage or improve its business operations.

7. The coming years will continue to be challenging for the public sector as it continues to be asked to do more, with less, for more people, in an increasingly complex and risky environment. It is important that entities can be assessed not just on what they spend, but on the difference they make. Ensuring that entities align their performance with long-term outcomes that matter most to the community and decision-makers is crucial. Performance statements that provide meaningful information can promote accountability, transparency, and genuine improvements in entity performance and public service delivery.

Performance of the public sector (chapter 1)

8. Meaningful annual performance statements are an important way for the Parliament, the government and the public to understand whether entities are operating efficiently and effectively in achieving their purposes, and delivering public value. Over time, as performance reporting matures, it may be possible to build a consolidated view of the performance of the public sector.

9. Of the 504 results5 reported by the 21 audited entities in 2024–25:

- 300 results met the targets (60 per cent);

- 66 results partially met the targets (13 per cent);

- 93 results did not meet the targets (18 per cent); and

- 27 results did not have a target, or were unable to be used against the target (five per cent); and

- 18 results were the basis for a qualified audit conclusion (four per cent).

10. These results suggest performance by the audited entities was mixed, with areas of high performance as well as room for improvement. However, a simple count of how many performance targets are ‘met’ or ‘not met’ is insufficient to assess public sector performance. A more complete view needs to consider context and factors outside the entity’s control, such as economic conditions, legal and regulatory constraints and technological change. Variations in the way performance information is collected and categorised or whether targets have been set ambitiously or conservatively, also affect how results should be interpreted.

11. The ANAO has observed substantial improvements in the quality of reporting since the commencement of the audit program, both in the scope of what is being reported, and in the clarity, consistency, and usefulness of the performance information presented by entities in annual performance statements. Despite these improvements, gaps and shortcomings remain that limit the insights and value provided by annual performance statements. For example:

- targets may reflect relatively low thresholds. As such, meeting these targets may not indicate high performance (paragraphs 1.15 to 1.19);

- entities can aggregate different topics and data sources in one measure. Aggregated performance measures can obscure important detail, mask poor or unbalanced outcomes and reduce transparency (paragraphs 1.25 to 1.27);

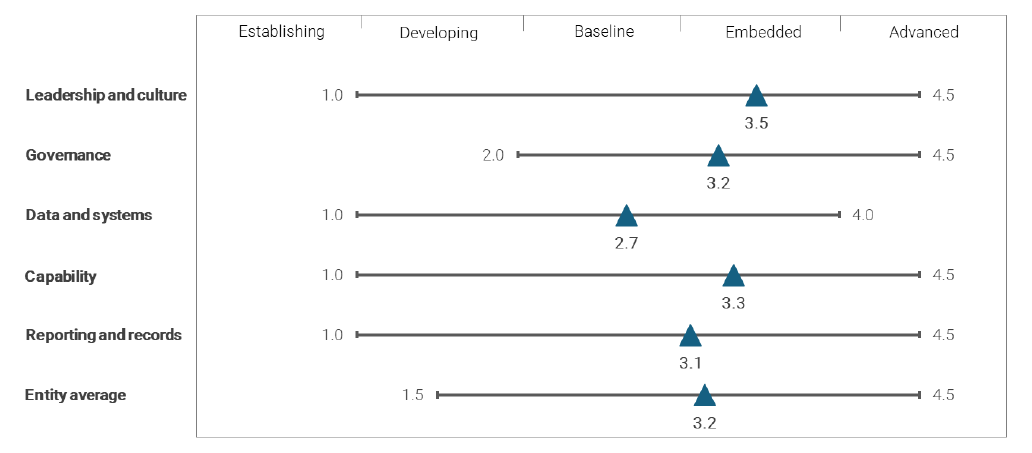

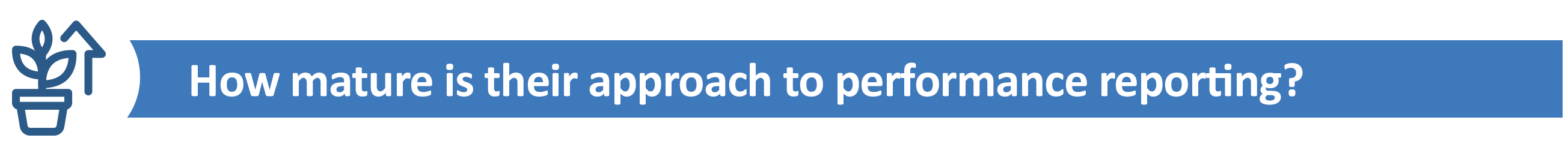

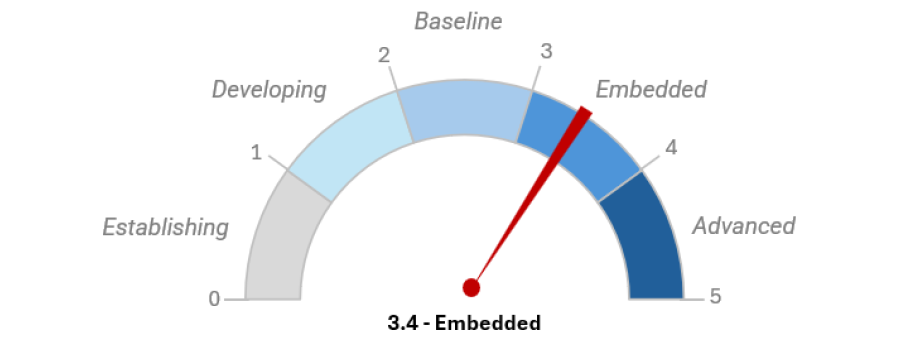

- some entities define performance below the target as ‘met’ (paragraph 1.30); and

- entities report inconsistently on similar functions — this makes it difficult to compare and benchmark performance across entities and to consider which approaches are working more effectively and why (paragraphs 2.47 to 2.52).

12. The nature and complexity of many government programs and services can make it difficult to measure certain aspects of their performance, requiring expertise and time to develop. This includes measuring:

- efficiency (more output for less input) — measurement of efficiency is rare across the sector.6 Without efficiency measures, it is difficult to know whether entities are delivering value for money, improvements or savings are possible, or whether public resources are being used well (paragraphs 1.32 to 1.39); and

- outcomes and impact — enable entities to move beyond measuring activity and expenditure to assessing whether their key activities are delivering their intended results and producing meaningful change to justify the level of investment (paragraphs 1.49 to 1.54).

13. Despite these challenges, the ANAO has observed that entities can take practical steps to strengthen the quality and usefulness of performance information, even when perfect measurement is not possible. This includes focusing on a mix of measures and supplementing quantitative measures with qualitative information, such as case studies, and insightful narrative and analysis. Better linking performance and financial information could provide another way of demonstrating that public money is being well managed and may overcome challenges in developing efficiency measures (paragraphs 1.40 to 1.47).

14. Presenting the auditor’s reports and the audited performance statements together in an entity’s annual report, as is the case for financial statements, would enable users to more readily assess whether the performance statements fairly present the entity’s performance in achieving its purposes in the reporting period and whether they can rely on the statements when making decisions, allocating resources or evaluating performance.

Assessing performance requires meaningful information (chapter 2)

15. The Commonwealth Performance Framework provides flexibility for entities to develop performance statements that reflect the nature and unique purposes of each entity. This recognises that entities differ in their functions, size and organisational form. The Framework acknowledges that when it comes to performance statements:

- one size does not fit all;

- entities need flexibility to decide how best to ‘tell their performance story’ in an appropriate and meaningful way; and

- entity performance information is likely to continue to evolve over time in response to the needs and expectations of the Parliament, government and the public.

16. The 2024–25 audit program shows that entities have improved their ability to produce performance statements that comply with the minimum requirements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule). However, audit findings show that simply meeting the minimum requirements does not necessarily produce information that is appropriate and meaningful for both the entity and external users of the performance statements. Many entities continue to primarily report what was done rather than showing what was achieved and statements can be disconnected from government priorities and long-term outcomes.

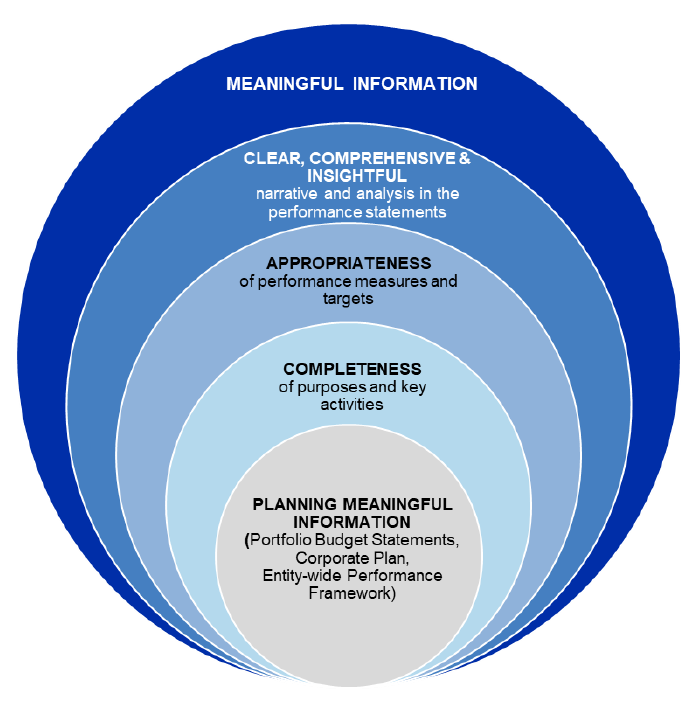

17. The Commonwealth Performance Framework does not define ‘meaningful information’, leaving entities without clear guidance for preparing effective performance statements beyond compliance only with the PGPA Rule. The ANAO has observed through its audit work that meaningful reporting involves setting out:

- ‘complete’ purposes and key activities (paragraphs 2.13 to 2.16);

- appropriate performance measures and targets (paragraphs 2.28 to 2.33); and

- clear, comprehensive and insightful narrative and analysis (paragraphs 2.40 to 2.46).

18. These elements are not always present in performance statements, even if the statements comply with the PGPA Rule. There is scope to clarify the Commonwealth Performance Framework to assist entities to better understand the qualities that make annual performance statements stakeholder focussed and meaningful (paragraph 2.8).

19. The effectiveness of many Australian government policies, programs and services can be difficult to measure and assess, particularly in a system of accountability that is focussed on individual entities. There are opportunities for the sector to consider:

- adopting common approaches to measuring similar functions or key activities across entities, such as regulation, compliance and claims processing, which could enable entities to identify better practices and benchmark their performance (paragraph 2.52); and

- leveraging linked programs in portfolio budget statements to enable performance reporting to move beyond individual entity achievements, facilitating more coordinated and coherent reporting of cross-cutting initiatives that can help users gain a clearer understanding of how well entities are working together and inform better analysis of the effectiveness of entities’ collaborative efforts in delivering public value and outcomes (paragraph 2.58).

20. One of the 21 entities audited by the ANAO reported a key activity on Closing the Gap. Of the 21 entities audited by the ANAO in 2024–25, only two had performance measures relating to Closing the Gap targets.

Performance reporting is improving — auditing incentivises improvement (chapter 3)

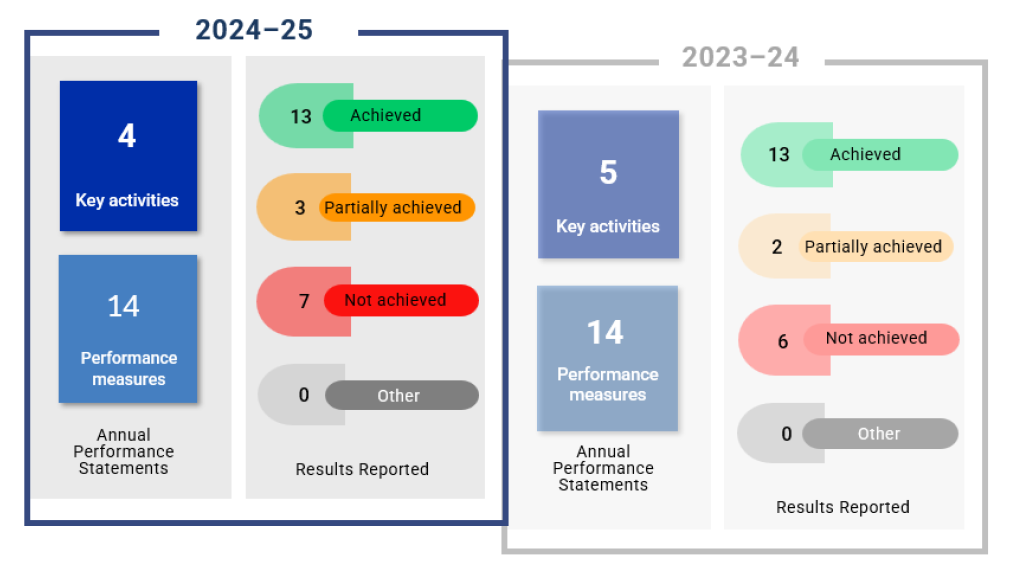

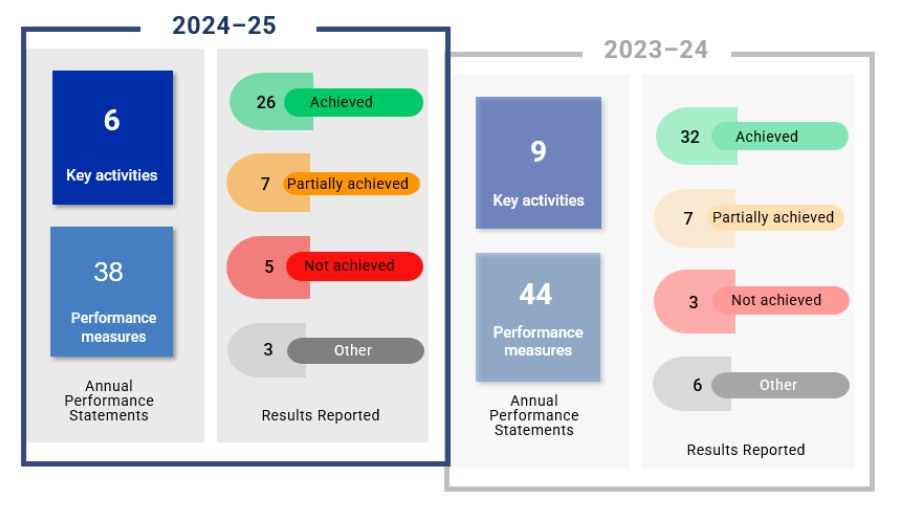

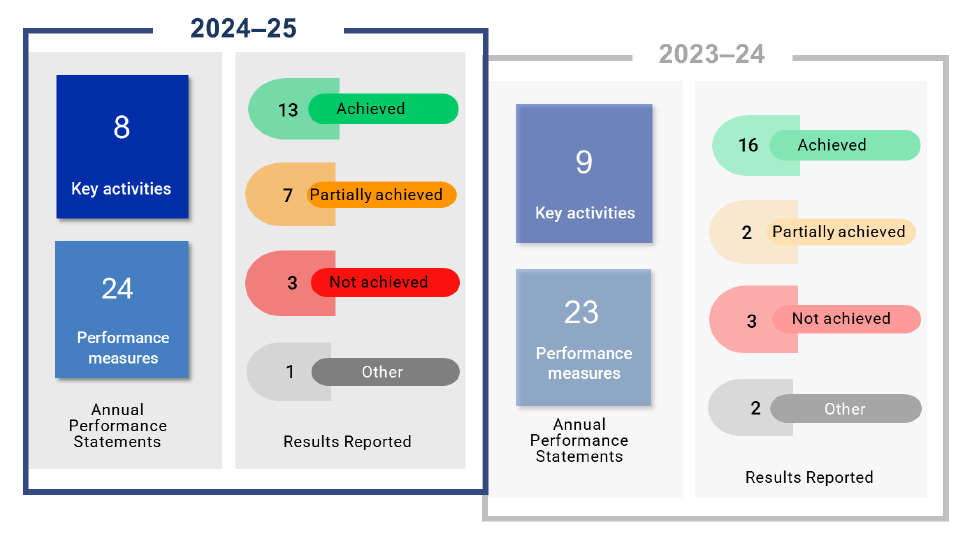

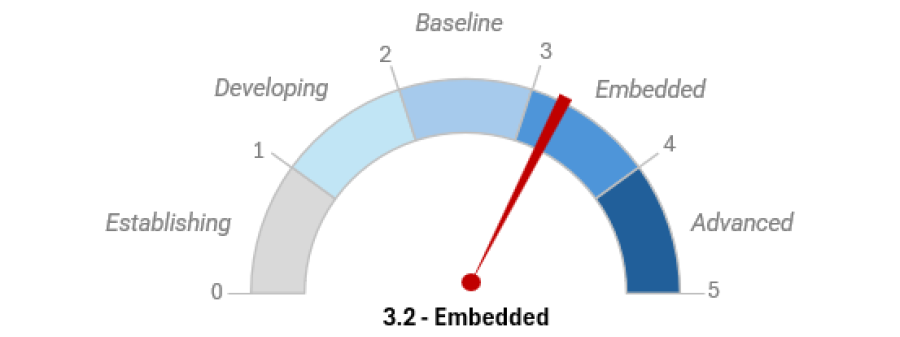

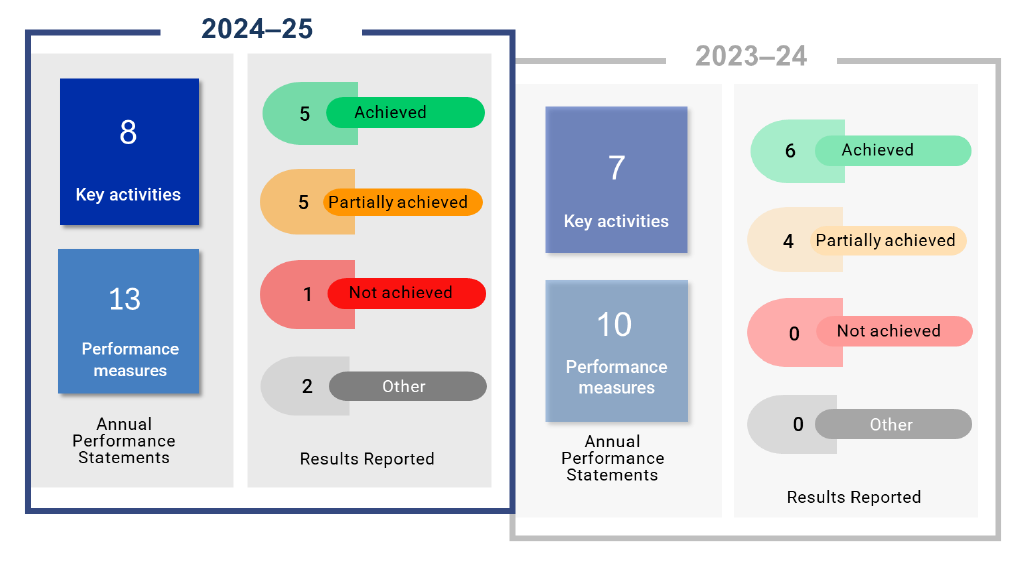

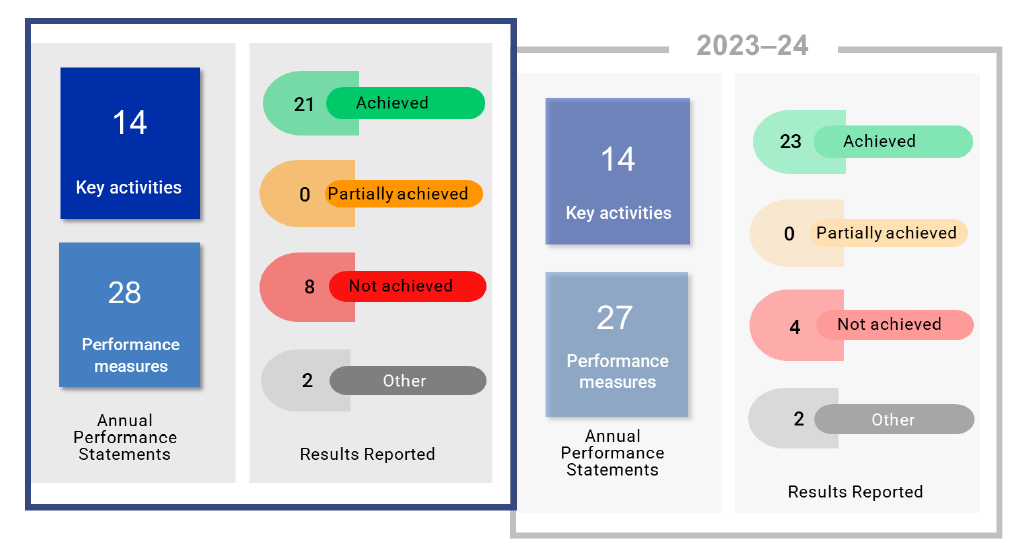

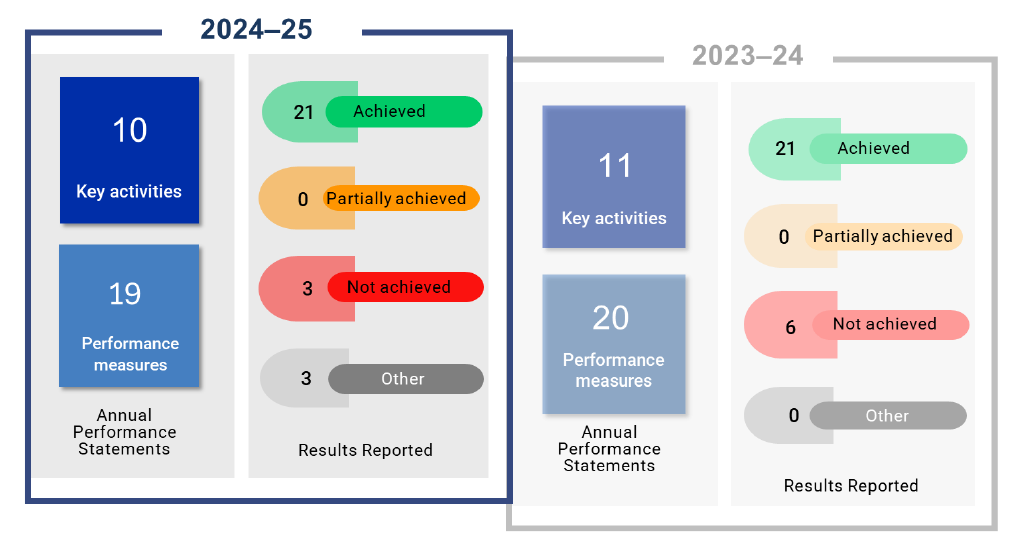

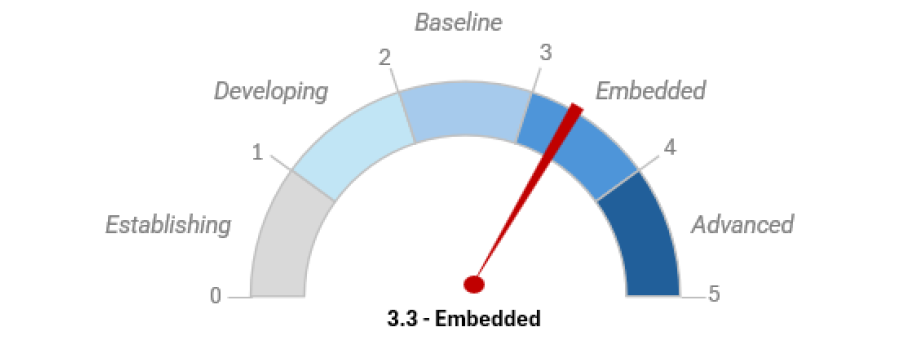

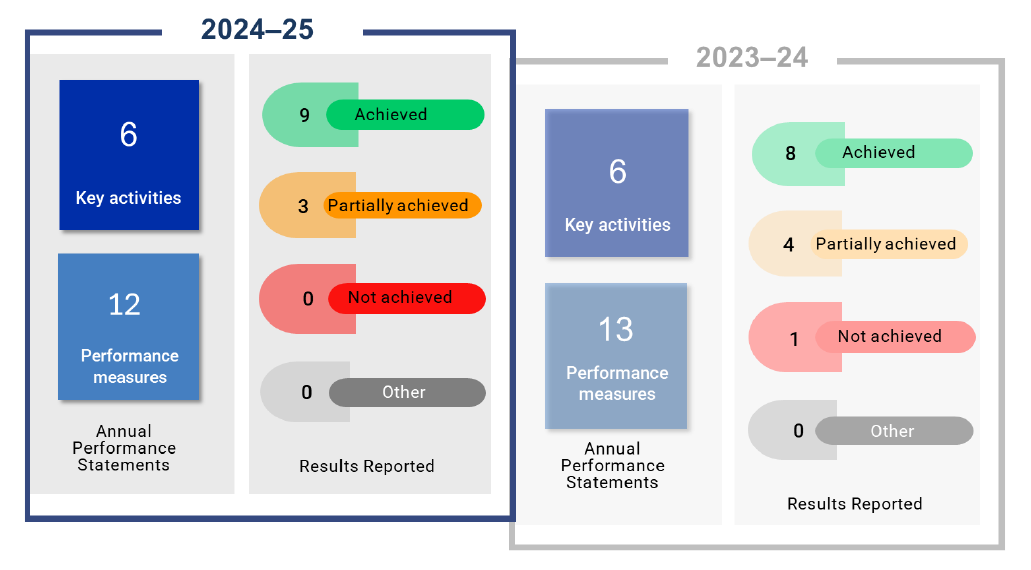

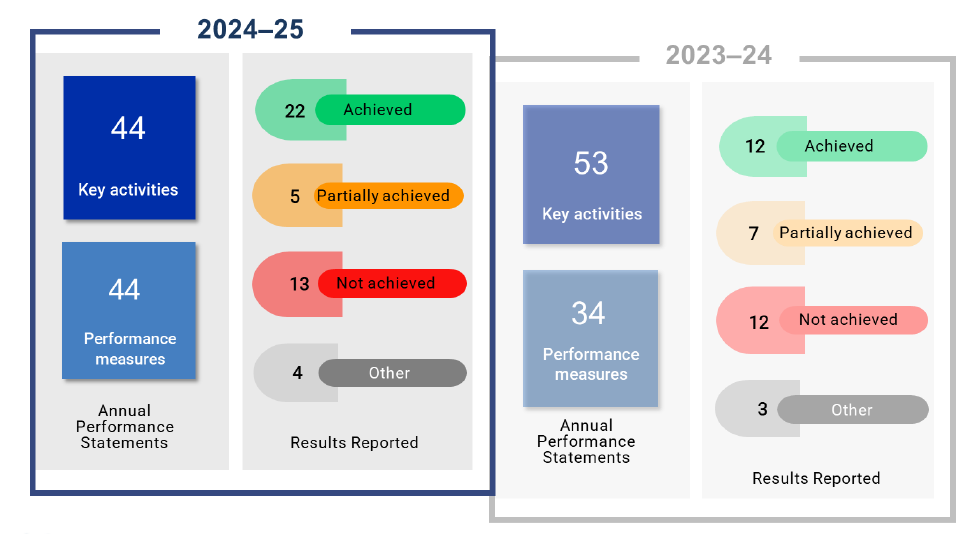

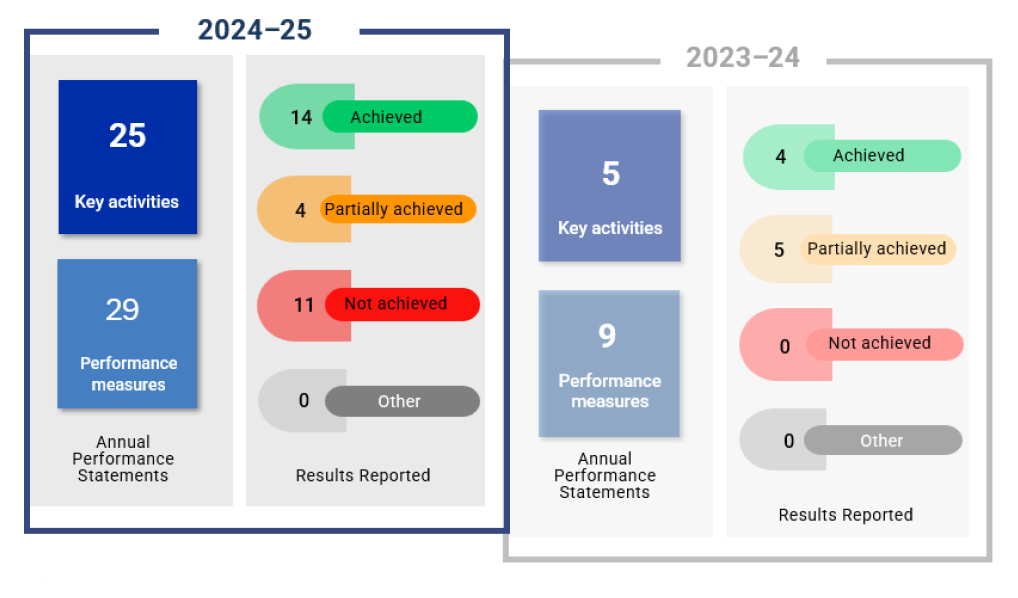

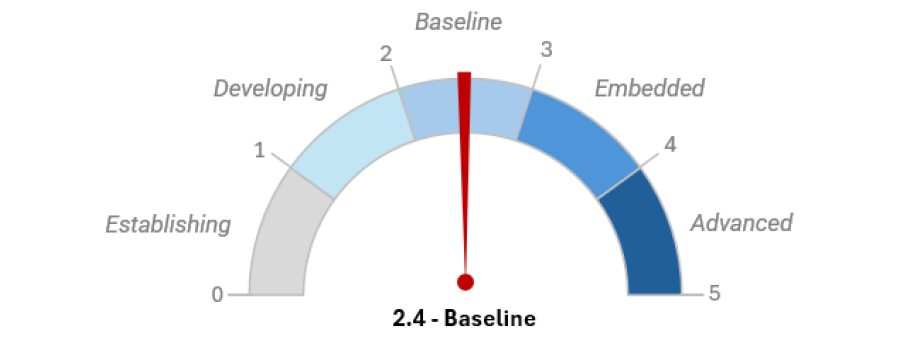

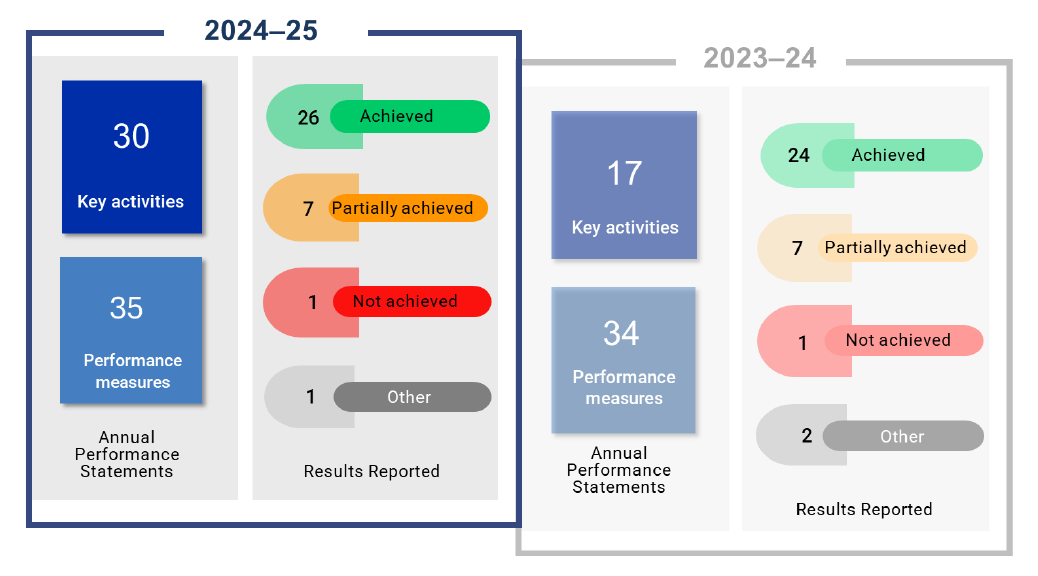

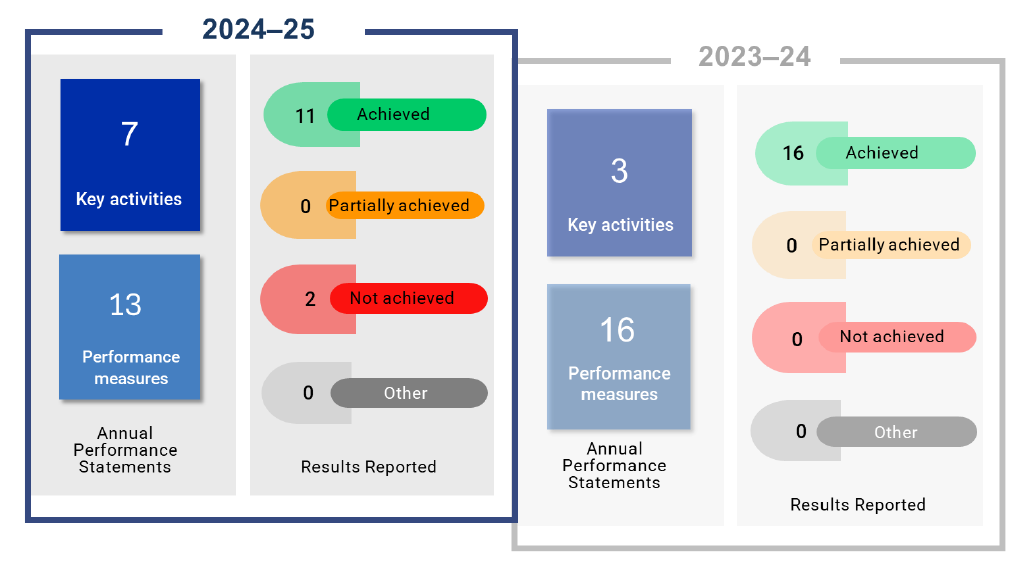

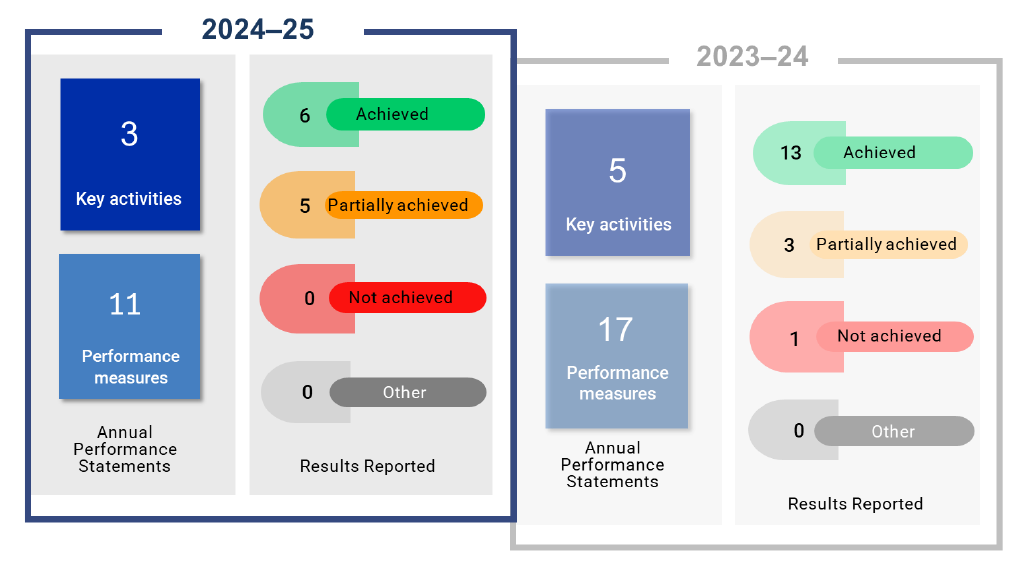

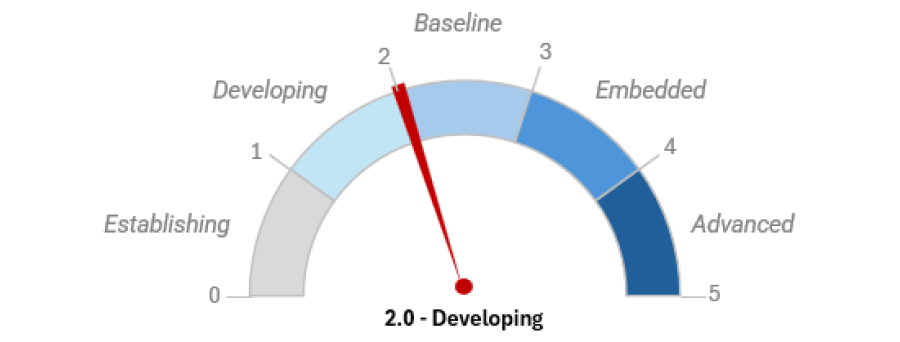

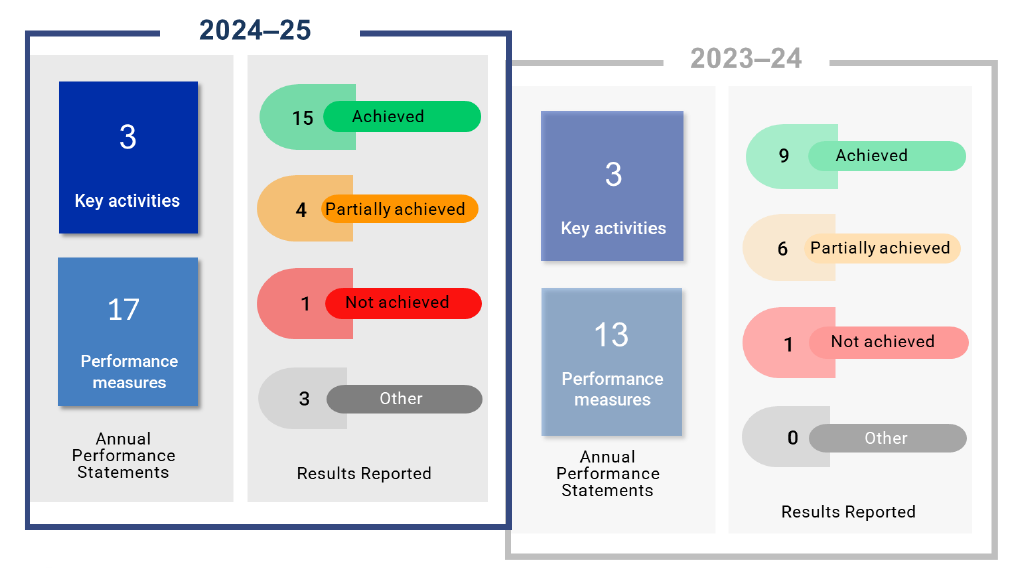

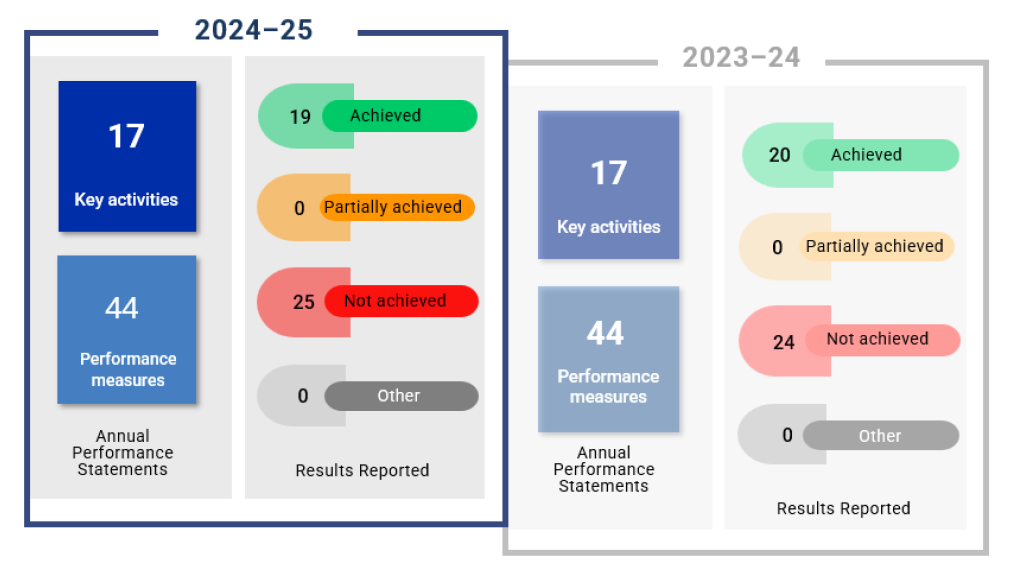

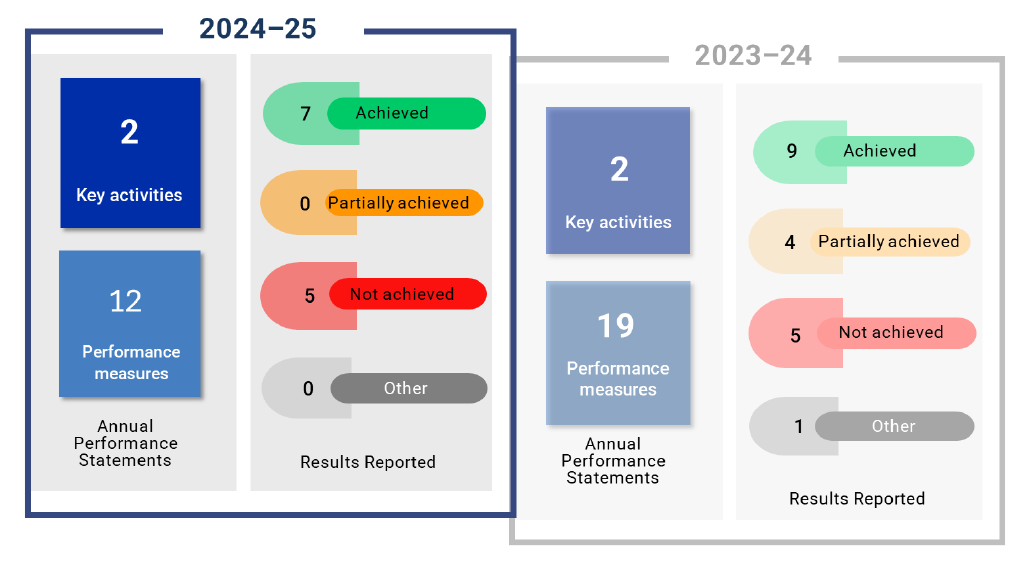

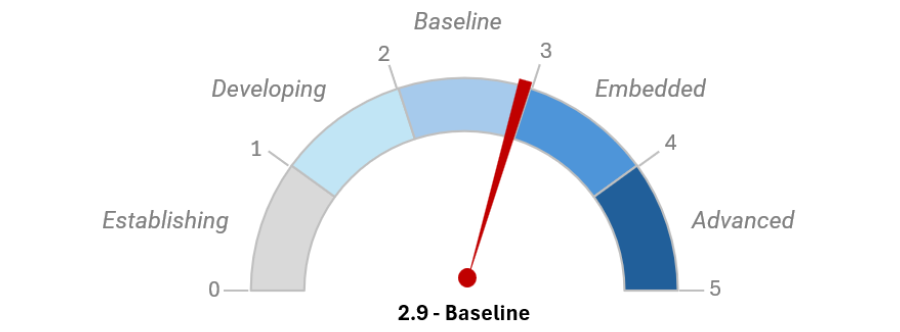

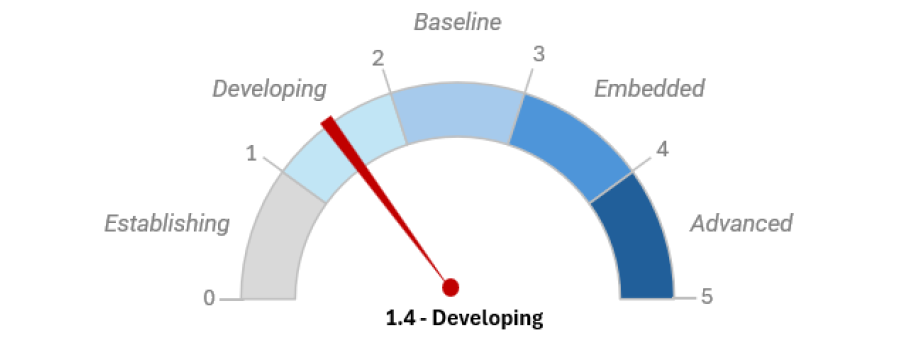

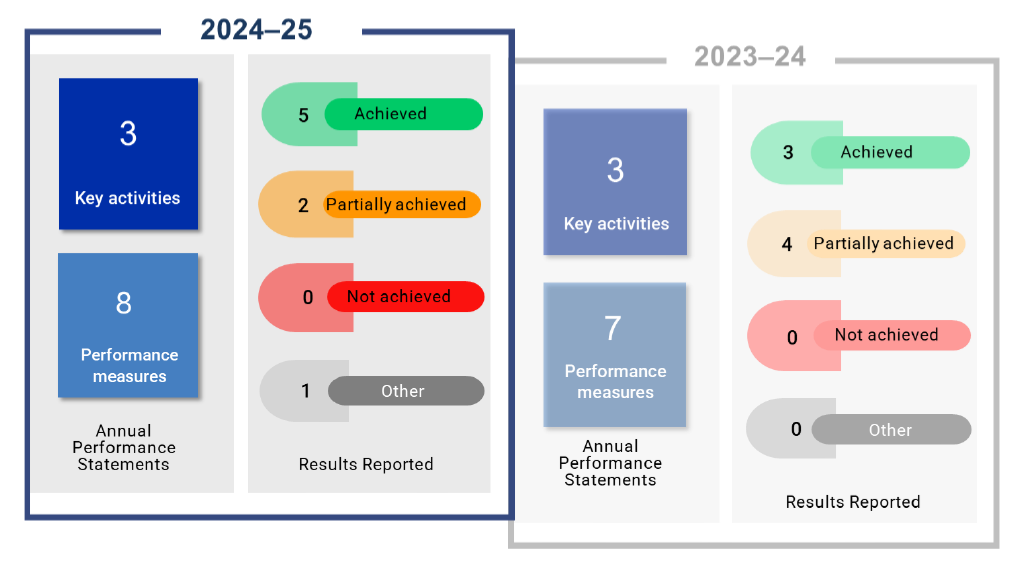

21. The outcomes of the 2024–25 audits show a continuing trend of improvement in performance reporting and in entities’ maturing capability to prepare performance statements. Of note:

- the proportion of entities that received a qualified audit conclusion in 2024–25 (29 per cent) decreased from 2023–24 (36 per cent);

- the same five auditees that received qualified conclusions in 2023–24 also received a qualified conclusion in 2024–25. However, the nature and extent of the qualifications were generally reduced compared to the previous year;

- new entities entering the audit program for the first time are better prepared — only one of the seven new entities audited for the first time in 2024–25 received a qualified audit conclusion;

- despite a 50 per cent increase in the number of auditees (from 14 to 21), a slightly lower number of findings was issued in 2024–25 (65) compared to 2023–24 (66). Only 46 per cent of final audit findings were significant or moderate in 2024–25, down from 70 per cent in 2023–24;

- of the 21 audited entities, two had no open findings at the close of the 2024–25 audits; and

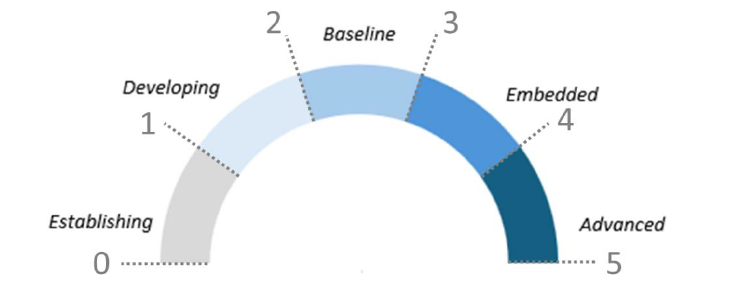

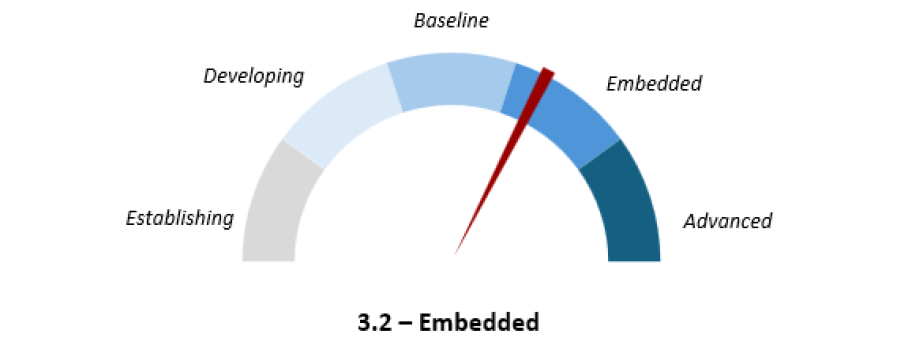

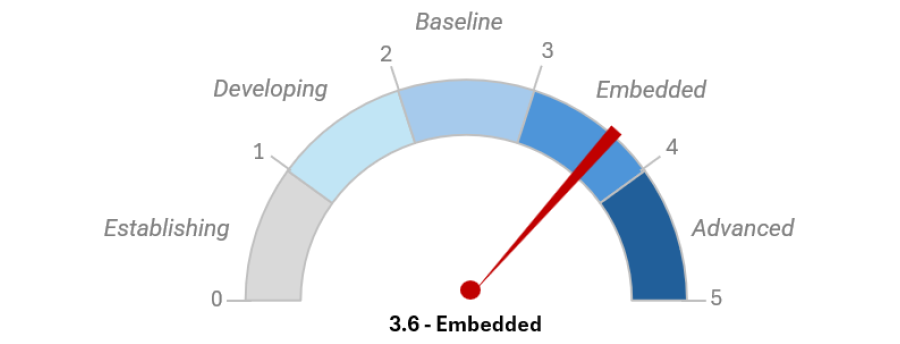

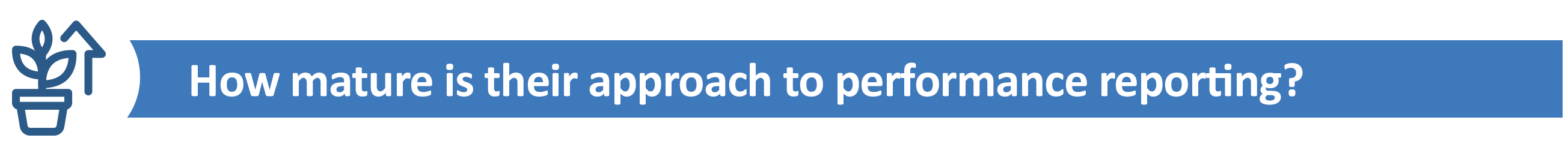

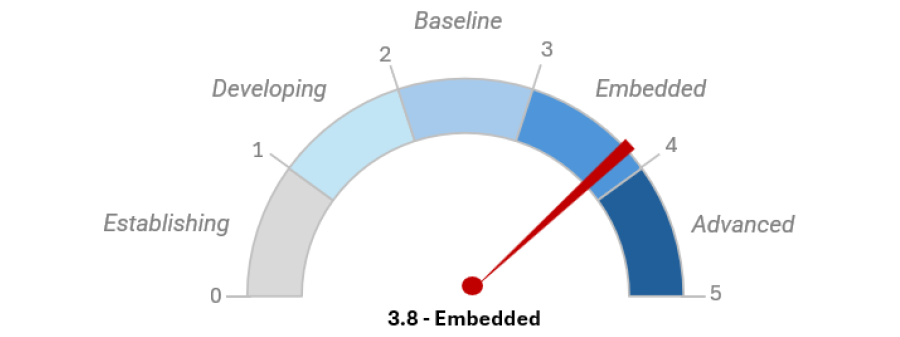

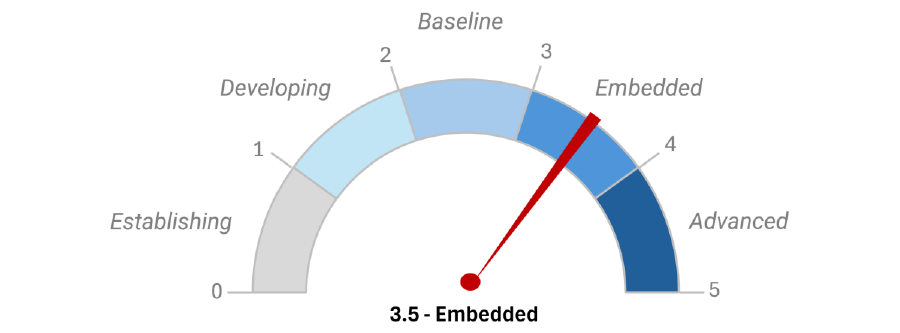

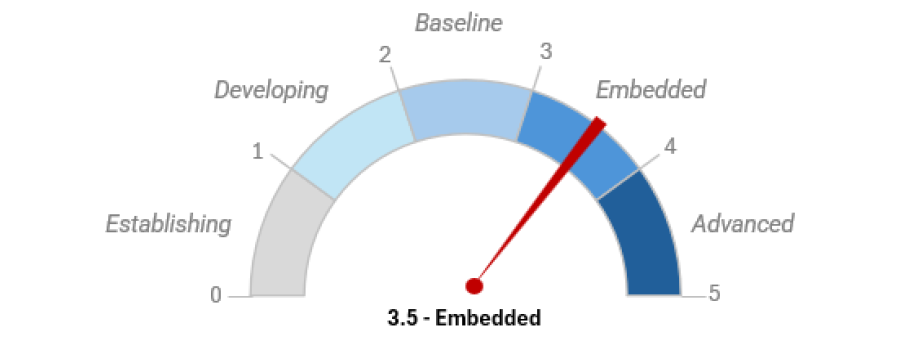

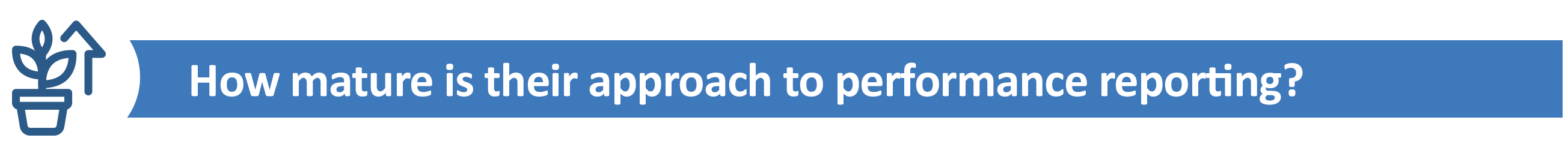

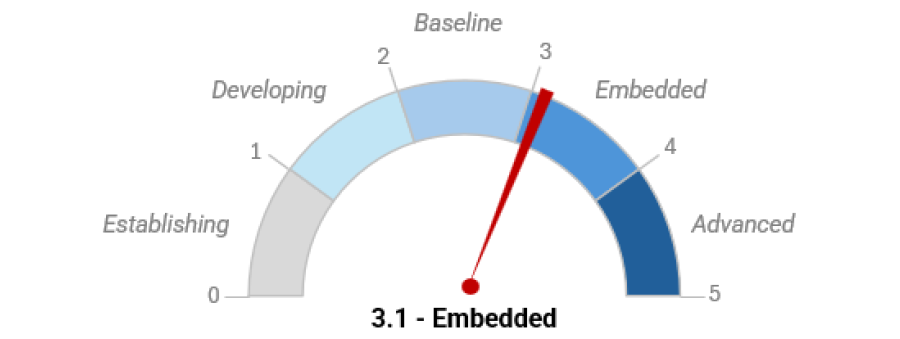

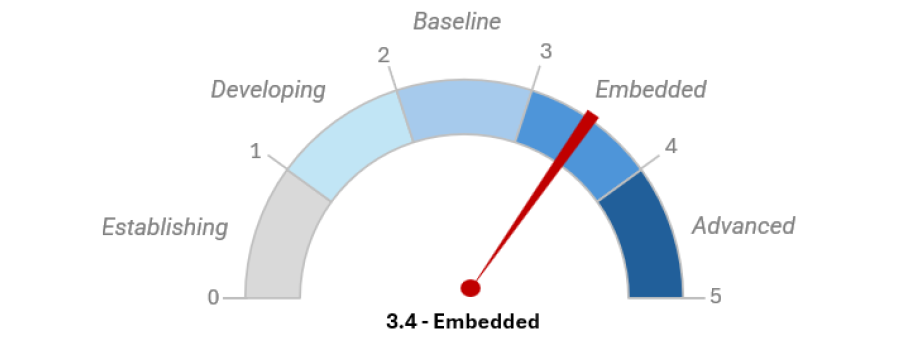

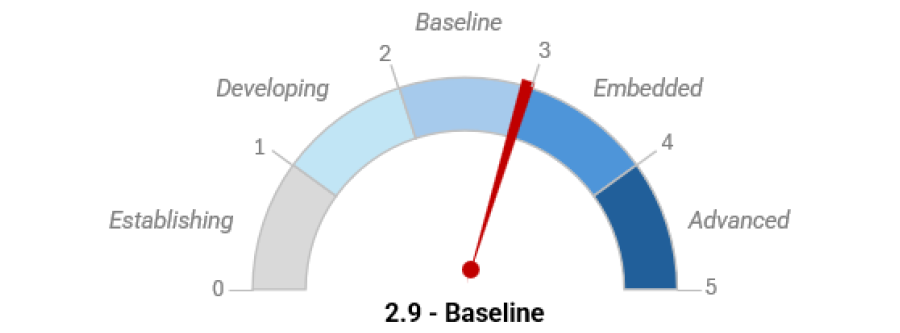

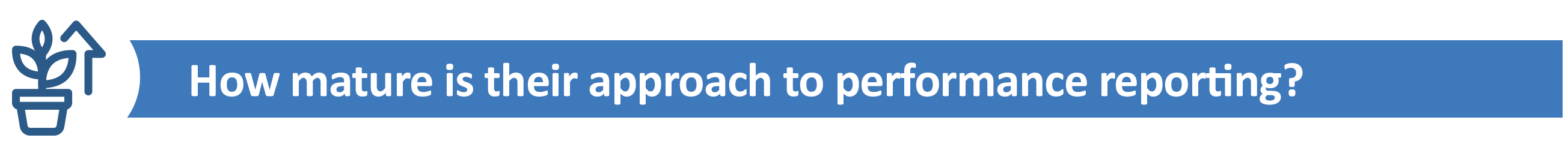

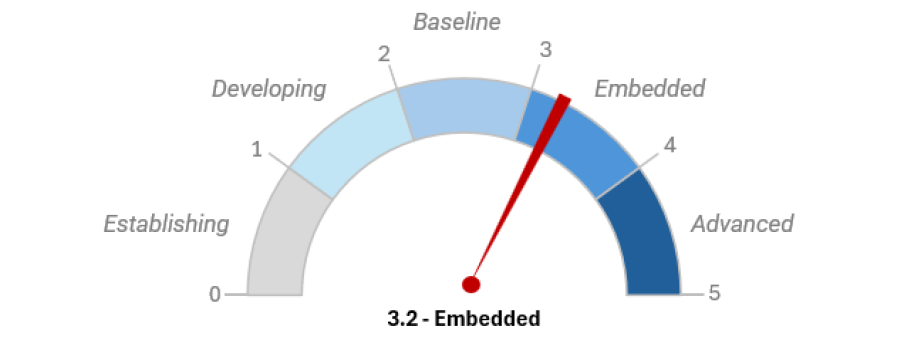

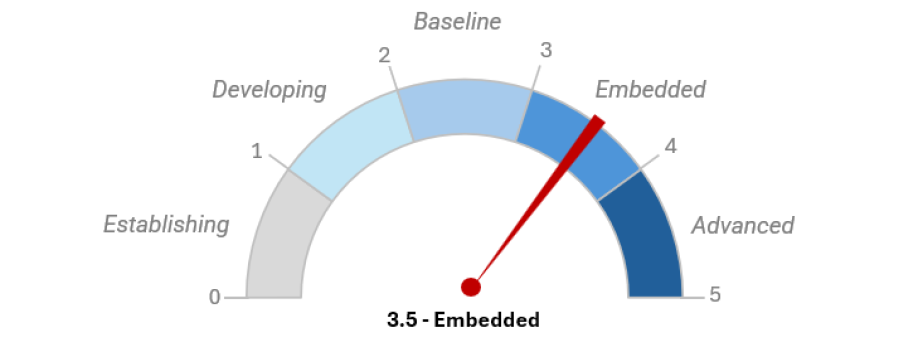

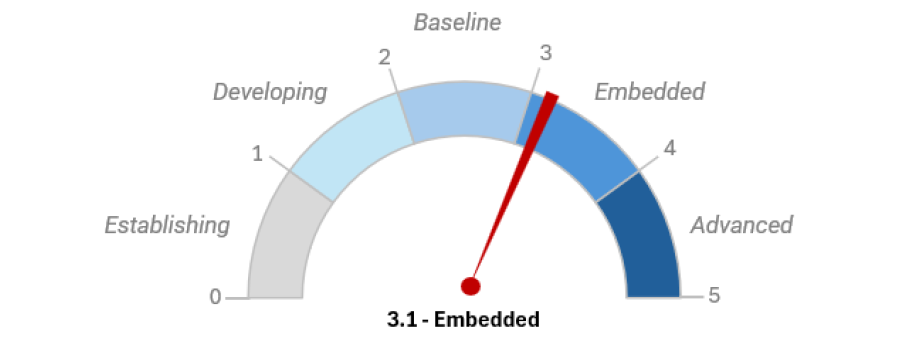

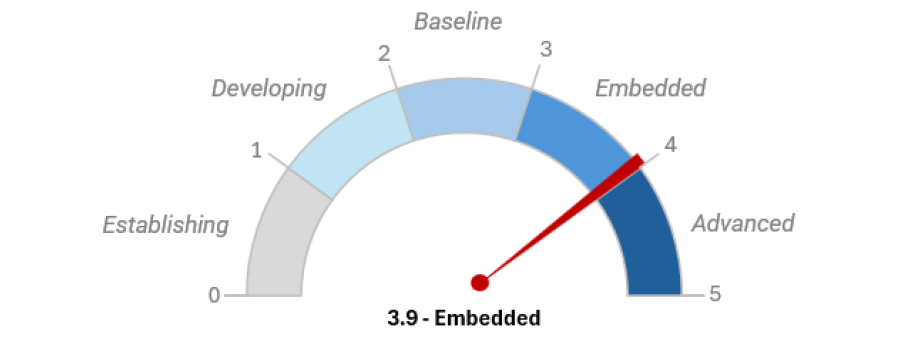

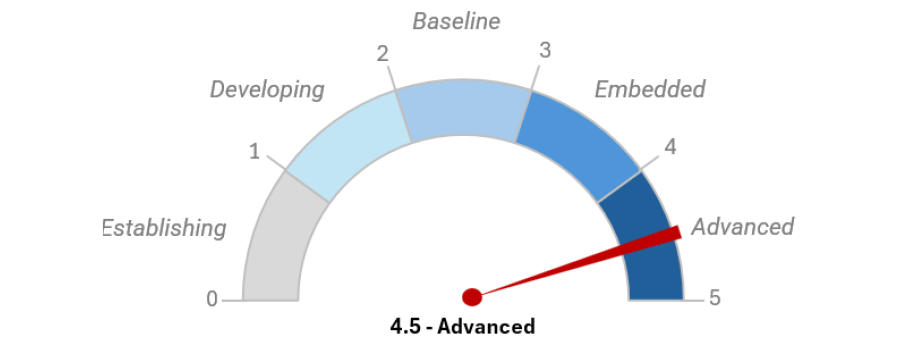

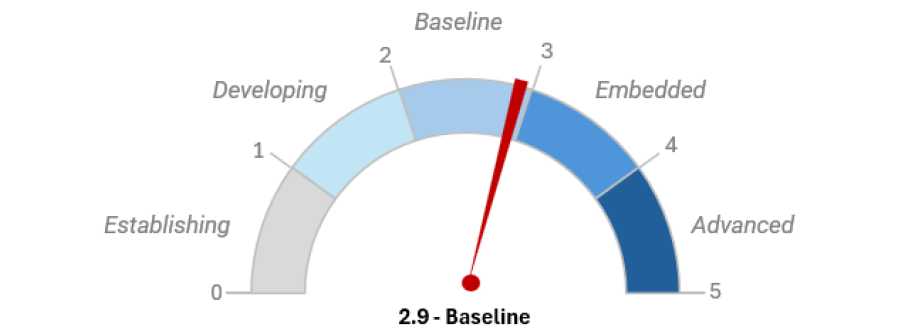

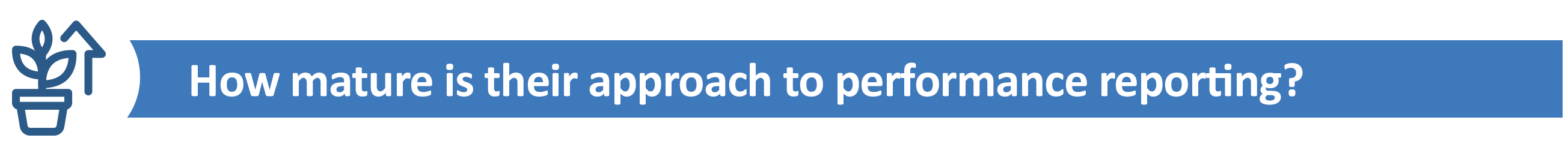

- the average maturity ratings of entities’ capability in the 2024–25 program increased from the prior year, but maturity still differs between entities. There were improvements in each of the five maturity categories assessed by the ANAO — leadership and culture, governance, data, capability, and records and reporting.

22. Growing performance reporting maturity across the sector helped to reduce audit costs. Across the 14 entities audited in both 2023–24 and 2024–25, total audit costs fell by 20 per cent. The key contributing factor was timely preparation of high-quality performance statements by entities. This was made possible by entities having well-organised, accurate and accessible records, reliable systems, well-documented internal controls and knowledgeable staff to liaise with the audit team. Audit experience shows that entities should not need to create additional records beyond those required for effective internal management and assurance to meet audit requirement. In principle, the records and information used for effective internal management, good governance, and decision-making should also be sufficient to support an external audit.

23. The improvement in performance reporting maturity — particularly in the ‘Leadership and culture’ and ‘Governance’ categories — demonstrates a shift from a compliance approach, where entities are focussed on complying with minimum reporting requirements. Instead, there is an increasing emphasis on the value of performance information for improving business operations and the delivery of government policies, programs and services (paragraphs 3.27 to 3.32).

24. The audit results show that the tone from the top has a powerful influence on good performance reporting. When senior leaders emphasise a performance and learning culture, staff feel responsible for producing high-quality data and are confident to report results fairly, even when performance falls short. This leads to more complete, balanced and useful performance statements that enables better public accountability.7

Future focus of performance statements auditing

25. The ANAO is examining options to refine its audit approach to improve audit quality and efficiency. An area of focus in 2025–26 will be the ANAO’s approach to assessing audit risk to inform the nature and scope of audit procedures. Continued refinement of the ANAO’s risk-based approach aims to further reduce audit costs in 2025–26 for both the ANAO and audited entities without impacting audit quality (paragraphs 3.45 to 3.48).

Opportunities for improvement

Opportunities for the Department of Finance

- To consider options to require the inclusion of the auditor’s report on the performance statements in the annual report for entities (paragraph 1.5).

- To introduce guidance material to assist entities to link resource information presented in portfolio budget statements to key activities or measures in performance statements (paragraph 1.48).

- To provide guidance for entities to report, in their performance statements, on the functions of statutory authorities and office holders that are financially and administratively supported within the entity (paragraph 2.19).

- To consider how entities can best present shared outcomes, entity contributions, and coordinated delivery in performance statements (paragraph 2.58).

Opportunities for auditees

- To establish performance targets that are challenging but achievable (paragraph 1.31).

- To include narrative and analysis in the performance statements that clearly explains performance against targets and trends over time (paragraph 1.31).

- When aggregated measures combine different topics or data sources in ways that obscure important performance details, ensure there is sufficient explanation of the important details to give readers clearer performance information (paragraph 1.31).

- To report performance information that demonstrates their efficiency and productivity, through the development of efficiency measures or linking financial and non-financial performance information (paragraph 1.36).

- To effectively report on shared outcomes to demonstrate effectiveness in addressing cross-cutting initiatives and collective impact (paragraph 2.58).

- To ensure there is a logical linkage between performance measures used for external accountability and internal management purposes (paragraph 3.31).

- To properly maintain records that enable effective governance and accountability, support evidence-based decision making, inform policy development and program evaluation. This also helps preserve corporate memory and provides assurance to the accountable authority and senior leaders that the information reported to the Parliament is reliable and accurate (paragraphs 3.45 to 3.48).

Opportunities for the ANAO

- To enhance the risk-based approach to auditing performance statements, guided by the risk profile and performance reporting maturity of an entity. This includes continuing to respond to areas of high risk, reduce audit effort and cost and improve audit quality and impact (paragraph 3.53).

- To report clearly on better practice, highlighting examples of effective performance frameworks, meaningful measures, and good data practices observed across entities, encouraging peer-learning and helping lift system-wide capability (paragraph 3.53).

- To set clear expectations through audit criteria, share insights on systemic issues affecting performance reporting and inform the Commonwealth Performance Framework, guidance or legislative reform where appropriate (paragraph 3.53).

1. Performance of the public sector

Introduction

1.1 Meaningful performance statements show what entities planned to achieve in the reporting period and how well they performed. If prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), they should provide meaningful information in a form that can be easily used by Parliament, government and the public to hold entities to account. They should help readers understand:

- the purposes and intended outcomes an entity has been funded to deliver;

- the key activities being undertaken by the entity in pursuit of those purposes and outcomes; and

- the results achieved, the impact the entity is having and the progress it is making.8

1.2 Financial statements are prepared under principles-based standards developed over many decades, which contain some detailed requirements regarding their structure, composition, measurement and disclosure. Their standardised format ensures they are prepared in a uniform way, enabling benchmarking across entities and sectors. The auditor’s report is presented in the entity’s annual report alongside the audited financial statements. This provides assurance that the financial statements fairly present the financial performance and position of the entity and are compliant with the financial reporting framework.

1.3 By comparison, annual performance statements are a relatively recent development, with Commonwealth entities being required to prepare them for the first time in the 2015–16 reporting period following the enactment of the PGPA Act. They are prepared under the principles-based Commonwealth Performance Framework, which provides flexibility for entities to customise their reporting to reflect their individual circumstances. Therefore, judgements need to be made about what performance information is most relevant and significant for the purpose of external reporting. These judgements can create challenges for both preparers and users, and may change over time. As a result, evaluating long-term performance trends and comparing performance across the sector can be difficult.

1.4 Unlike financial statements, the auditor’s reports on the performance statements are tabled in the Parliament by the Minister for Finance and are not included in the annual reports of audited entities. This separation makes it more difficult for a reader of the performance statements to know whether the statements fairly present the entity’s performance in achieving its purposes in the reporting period and if they are compliant with the performance reporting framework. There would be benefit in presenting the auditor’s reports alongside the audited performance statements, consistent with the current approach for financial statements, to ensure the reader receives assurance regarding the entity’s performance reporting.

Opportunity for improvement

1.5 The Department of Finance could consider options to require the auditor’s report on the performance statements to be included in the annual report for entities, to provide readers with assurance that the audited performance statements are presented fairly.

Assessing the performance of the Australian public sector

1.6 The Commonwealth Performance Framework requires the accountable authority of each Commonwealth entity to measure and assess the entity’s performance in achieving its purposes. It is a devolved framework with discretion for the accountable authority to determine the most appropriate method for measuring, assessing and reporting on their entity’s results and outcomes. Key terms used in the report for describing entity performance are outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Key performance terms

|

Term |

Description |

|

Measure |

A performance measure is a specific indicator used to assess how well an entity is achieving an intended objective or outcome. It defines what is being measured and how success is evaluated. |

|

Target |

A performance target is the desired level of performance for a given measure or aspect of a measure, within a set time period. It specifies how much performance is expected and serves as a benchmark for success. |

|

Result |

A performance result is the actual level of performance achieved for a target over a set period of time. It shows what was accomplished and is used to compare against the target. |

1.7 A performance measure may have multiple performance targets. Some entities report their results against each target separately (see for example the Department of Social Services measure 2.1.5-1). Other entities aggregate performance across targets and report an overall result against the measure (see for example the Department of Defence measure 4.1). For consistency, the ANAO has referred to ‘results’ in this chapter to refer to entities’ assessments of their performance, irrespective of whether these results are reported at the measure level or target level.

1.8 The flexibility provided by the Commonwealth Performance Framework means performance statements and measurement frameworks differ significantly from entity to entity. This includes differences in how entities define achievement or success against a performance measure or target. Most entities use at least three categories to describe their results:

- fully met/achieved;

- partially met/achieved9; and

- not met/achieved.

1.9 The tolerances for each of these categories vary between entities. For example, if a result was 80 per cent against a target of 100 per cent, the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet would report ‘substantially achieved’10, Services Australia would report ‘partially achieved’, and the Department of Home Affairs would report ‘not met’. This reduces the comparability of performance results between entities.

1.10 Another challenge in evaluating the aggregate performance of the Australian public sector is that the number of results an entity reports may not be proportional to its size, role in the public sector or contribution to the lives of Australians. For instance, Services Australia, an entity that provides services to almost every Australian11, reported eight results out of the 504 reported by the 21 audited entities in 2024–25.12 By comparison, the ATO reported 41 performance results in 2024–25, the National Disability Insurance Agency reported 12 results (down from 19 results in 2023–24) and the Department of Parliamentary Services reported 13 results.

Performance against targets

1.11 Performance targets give context to reported performance information and provide the foundation for credible performance measurement, transparent public reporting, and robust accountability for the use of public resources. In the absence of targets, performance statements tend to become descriptive, making it difficult to assess whether an entity has delivered on its commitments, public funds have been used effectively, or performance information is appropriate and meaningful.

1.12 Table 1.2 shows the performance results reported by audited entities in 2024–25, including how many results were reported as met, partially met, not met, or not assessed against the targets.

Table 1.2: Performance results reported by entity in 2024–25

|

Entity |

Results met |

Results partially met |

Results not met |

Results not assessed |

Total results reporteda |

||||

|

|

# |

% |

# |

% |

# |

% |

# |

% |

# |

|

Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) |

13 |

57 |

3 |

13 |

7 |

30 |

0 |

0 |

23 |

|

Australian Taxation Office (ATO) |

24 |

62 |

7 |

18 |

5 |

13 |

3 |

8 |

39 |

|

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (DAFF) |

13 |

54 |

7 |

29 |

3 |

13 |

1 |

4 |

24 |

|

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) |

17 |

71 |

5 |

21 |

2 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

24 |

|

Department of Defence |

5 |

38 |

5 |

38 |

1 |

8 |

2 |

15 |

13 |

|

Department of Education (DoE) |

21 |

68 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

26 |

2 |

6 |

31 |

|

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (DEWR) |

21 |

78 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

11 |

3 |

11 |

27 |

|

Department of Finance (Finance) |

25 |

68 |

5 |

14 |

1 |

3 |

6 |

16 |

37 |

|

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) |

9 |

75 |

3 |

25 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

|

Department of Health, Disability and Ageing (DHDA) |

20 |

56 |

3 |

8 |

10 |

28 |

3 |

8 |

36 |

|

Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs) |

11 |

46 |

3 |

13 |

10 |

42 |

0 |

0 |

24 |

|

Department of Industry, Science and Resources (DISR) |

12 |

67 |

4 |

22 |

1 |

6 |

1 |

6 |

18 |

|

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts (DITRDSCA) |

26 |

74 |

7 |

20 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

35 |

|

Department of Parliamentary Services (DPS) |

11 |

85 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

15 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

|

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) |

6 |

55 |

5 |

45 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

|

Department of Social Services (DSS) |

15 |

63 |

1 |

4 |

8 |

33 |

0 |

0 |

24 |

|

Department of the Treasury |

15 |

65 |

4 |

17 |

1 |

4 |

3 |

13 |

23 |

|

Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) |

19 |

44 |

0 |

0 |

24 |

56 |

0 |

0 |

43 |

|

National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) |

7 |

58 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

42 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

|

National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) |

5 |

56 |

2 |

22 |

1 |

11 |

1 |

11 |

9 |

|

Services Australia |

5 |

63 |

2 |

25 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

13 |

8 |

|

Total |

300 |

62 |

66 |

14 |

93 |

19 |

27 |

5 |

486 |

Note a: This table excludes results that formed part of the basis for a qualified audit conclusion.

Note: Some of the results ‘not assessed’ include where the entity has established a baseline.

Note: Some percentages for an entity do not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Source: ANAO analysis of entities’ annual performance statements. As per Footnote 3, this table has rolled up all entity performance assessments that were less than fully met, but more than not met, into the single category of ‘partially met’.

1.13 When excluding performance measures that were the basis for a qualified audit conclusion13, the 21 audited entities reported 486 performance results as follows:

- 300 results met the targets (62 per cent);

- 66 results partially met the targets (14 per cent);

- 93 results did not meet the targets (19 per cent);

- 27 results did not have a clear target, or were unable to be used to assess performance against the target (6 per cent).14

1.14 These results suggest a mixed level of performance, with areas of high performance as well as room for improvement. This simple count of how many performance targets are ‘met’ or ‘not met’ has limitations. A more complete understanding of performance needs to consider context and factors outside the entity’s control, such as economic conditions, legal and regulatory constraints and technological change. Variations in how performance information is collected and categorised or whether targets have been set ambitiously or conservatively, also affects how results should be interpreted.

1.15 For example, targets may reflect relatively low thresholds that are not ‘challenging but achievable’.15 Where an entity regularly exceeds its performance targets by large margins, it may be appropriate to consider whether the targets are set correctly to reflect ‘challenging but achievable’ thresholds that drive improvement.16

1.16 Further examination of the performance information is necessary to understand the degree of underperformance or overperformance. Missing a target by a narrow margin (for example, achieving 94 per cent against a 95 per cent target) is fundamentally different from significant underperformance, yet both may be counted as ‘not met’.17 Similarly, substantially exceeding a target does not show up in a simple count.

1.17 Table 1.3 shows that the Department of Health, Disability and Ageing has reported in the past two reporting periods on a measure relating to preventable hospitalisations that was ‘not met’ in both years but shows a significant drop in performance between years.

Table 1.3: Performance against Department of Health, Disability and Ageing performance measure: The number of Primary Health Network regions in which the rate of potentially preventable hospitalisations is declininga

|

Results |

2023–24 |

2024–25 |

ANAO analysis |

|

Target |

27 regions |

28 regions |

N/A |

|

Performance against target |

Not met |

Not met |

No change is apparent from the high-level result. |

|

Actual results |

24 regions |

2 regions |

Performance declined substantially in 2024–25. The department investigated the causes for this decline, and in its analysis for this measure, reported that ‘the observed increase in [potentially preventable hospitalisations] may be attributable to a notable decline in complex care management in the general practice sector in the previous period’. |

Note a: The full measure as published by the department is ‘The number of Primary Health Network regions in which the rate of potentially preventable hospitalisations is declining, based on the latest available Australian Institute of Health and Welfare longitudinal data’.

Source: Department of Health, Disability and Ageing 2024–25 Annual Performance Statements and Department of Health and Aged Care 2023–24 Annual Performance Statements

1.18 This example highlights the risk of relying exclusively on categorical assessments of ‘met’, ‘partially met’ or ‘not met’ to assess entity performance or whole of sector performance.

1.19 Narrative and analysis can play an important role in helping an entity explain why a performance target was not met and in maintaining the credibility and usefulness of the performance statements, as shown in Table 1.3. To assist the reader, the accompanying narrative and analysis could explain why the result happened, what it means, and planned next steps. The analysis could also describe what the entity could have influenced and what was outside its control.

Performance over time

1.20 Another dimension for evaluating the performance of the Australian public sector is to analyse performance over time. The PGPA Rule requires that an entity’s performance measures must provide a basis for an assessment of the entity’s performance over time.18 Resource Management Guide 131 explains the context for this requirement:

Many of the objectives of government are ones that will only be achieved over the medium to long term. Therefore, the ability to measure performance over time provides an entity and stakeholders with a more informed view of the entity’s progress in achieving its purposes.19

1.21 Table 1.4 presents the reported performance results for the 10 entities that the ANAO has audited since 2022–23 (excluding results that were the basis for a qualified audit conclusion).

Table 1.4: Performance over time for audited entitiesa, 2022–23 to 2024–25

|

Reported result |

Results in 2022–23 |

Results in 2023–24 |

Results in 2024–25 |

|||

|

|

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

|

Met |

144 |

57 |

153 |

61 |

159 |

60 |

|

Partially met |

25 |

10 |

30 |

12 |

31 |

12 |

|

Not met |

56 |

22 |

59 |

23 |

63 |

24 |

|

Not assessedb |

26 |

10 |

10 |

4 |

12 |

5 |

|

Total results reported in-yearc |

251 |

100 |

252 |

100 |

265 |

100 |

Note a: The 10 entities that have been included in the ANAO’s audit program since 2022–23, and presented in this analysis, are: Attorney-General’s Department, Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Department of Education, Department of Health, Disability and Ageing, Department of Industry, Science and Resources, Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts, Department of Social Services, Department of the Treasury, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, and Services Australia.

Note b: The ‘Not assessed’ category includes measures with no target to assess performance against, or measures where data was not available to report a result.

Note c: Across all results reported in this table, 19 have been excluded as they were the basis of a qualified audit conclusion.

Note: Some percentages do not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Source: ANAO analysis of entities’ annual performance statements.

1.22 Table 1.4 indicates that over the last three years, there have been slight increases in both the proportion of results reported as ‘met’, and in the proportion of measures reported as ‘not met’. There has also been a decline in the proportion of measures in the ‘other’ category, which may indicate an improvement in the quality of reporting as fewer measures lacked targets, or data on which to base performance assessment against the targets. Given the short time period covered and aggregate nature of this summary, it is not possible to draw firm conclusions from this data.

1.23 A richer assessment of performance over time can be obtained by complementing the information in Table 1.4 with analysis regarding the proportion of results that have increased, decreased or remained stable irrespective of whether the result is reported as ‘met’ or ‘not met’. For example, of the 14 entities audited in both 2023–24 and 2024–25:

- the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade reported 12 measures in 2024–25, all of which were also reported in 2023–24.20 In 2024–25 the department reported nine results as met and three results as partially met. Compared to 2023–24, results improved for two of the measures in 2024–25, remained steady for nine measures and declined for one measure;

- the Department of Industry, Science and Resources reported 95 per cent of the same measures in 2024–25 as in 2023–24. In 2024–25, it reported 12 results as met, four results as partially met and one result as not met. Compared to 2023–24, results improved for four of the comparable measures in 2024–25, remained steady for eight measures and declined for five measures; and

- Services Australia reported 88 per cent of the same measures in 2024–25 as in 2023–24. In 2024–25, it reported five results as met and two results as partially met. Compared to 2023–24, results improved for two of the comparable measures in 2024–25 and remained steady for five measures.

1.24 As the quality of information presented in performance statements improves, it will become increasingly possible to track performance over time and gain insights on whether public funds have been used effectively and efficiently to achieve intended results. Table 1.5 shows an example of fluctuation in performance over time, and associated performance narrative that describes the reasons for change.

Table 1.5: Department of Employment and Workplace Relations’ performance measure: Average processing time for initial claims under the Fair Entitlements Guarantee program

|

Target |

2023–24 result |

2024–25 result |

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations narrative |

|

14 weeks or less |

17.3 weeks (not achieved) |

13.8 weeks (achieved) |

The department implemented a number of strategies that contributed to this improvement, including proactive early engagement with insolvency practitioners on larger cases to support the receipt of more timely and higher quality entitlements data and internal revisions to the operational oversight, processes, management and assessment of claims. |

Source: ANAO analysis of the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations 2024–25 Annual Performance Statements.

The risk of aggregated performance measures

1.25 Performance measure design can impact effective performance assessment and reporting, especially where entities aggregate different topics and data sources in one measure. Aggregated performance measures present risks because they can obscure important detail, mask poor or unbalanced outcomes and reduce transparency.

1.26 For example, in Services Australia’s measure on work processed within timeliness standards, the result is driven by the work type, ‘Health’. Services Australia’s 2024–25 performance statements explain that: ‘The result was influenced by automated health processing, which accounts for 98.8% of all work included in this measure’.21 In other words, social security claims, child support payments, emergency payments and non-automated Health processing account for only 1.2 per cent of all work included in the measure.

Table 1.6: Results against Services Australia performance measure: Work processed within timeliness standards

|

Target |

Reported result (%) |

Results by work type (%) |

|

|

≥90% |

92.4 (achieved) |

Social security |

85.9 |

|

Health |

92.4 |

||

|

Child support payments |

52.3 |

||

|

Emergency payments |

77.0 |

||

Source: Services Australia 2024–25 Annual Performance Statements, Table 15, p. 24.

1.27 The disaggregated information in Table 1.6 is presented in Services Australia’s 2024–25 performance statements. However, aggregating performance across the four work types has enabled an overall performance result of ‘Achieved’ to be reported. If the measure was designed to set the target for each work type separately, three out of four work types would have failed to meet the target. Entities should consider whether the information presented meets users’ needs.

Labelling results

1.28 Gaining an accurate view of performance depends on the quality of performance information. This includes consideration of what and how targets are set (see Chapter 2).

1.29 To account for the vast differences in agency activity, the PGPA Rule enables entities to use discretion in describing their results. However, it is important that these descriptions are reasonable. The integrity of targets may be reduced if an entity can claim performance below a target as fully ‘met’.

1.30 In 2024–25, the Department of Home Affairs and the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts both defined performance below the target as achieving the threshold of ‘met’.22 The auditor’s reports for both departments included an Emphasis of Matter paragraph, drawing the reader’s attention to this method of assessing performance.

Opportunity for improvement

1.31 Entities could improve the quality of performance reporting by ensuring that:

- targets are challenging but achievable;

- narrative and analysis in the performance statements clearly explain performance against targets and trends over time; and

- when aggregated measures combine different topics or data sources in ways that obscure important performance details, ensure there is sufficient explanation of the important details to give readers clearer performance information.

Measuring public sector efficiency

1.32 Efficiency is generally measured as the price of producing a unit of output and is generally expressed as a ratio of inputs to outputs.23 Efficiency measures are central to assessing stewardship in the public sector by demonstrating how well government entities use the resources entrusted to them to deliver government programs and services. If efficiency cannot be measured, productivity cannot be meaningfully assessed.24 Section 16EA of the PGPA Rule requires entities to report a mix of output, efficiency and effectiveness measures (that is, entities should seek to measure efficiency).

1.33 The 21 audited entities reported only four efficiency measures, as assessed by the ANAO. A further two measures had multiple targets, some of which addressed efficiency. These six measures are identified in Table 1.7.

Table 1.7: Performance measures and results addressing entity efficiency

|

Entity |

Measure |

Target |

Result |

|

Australian Taxation Office |

Cost of collection – Cost to collect $100 |

+/- 5c from previous year |

$0.54 (incl GST) $0.51 (excl GST) (Met) |

|

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry |

Equal or reduced cost of levies administration compared with levies disbursed |

Levies administration cost is less than or equal to 1.2% of levies disbursed |

1.10% of levies disbursed (Met) |

|

Services Australia |

Cost per payment dollar administered |

Set benchmark |

2.02% (Unable to assess against a target of ‘Set benchmark’) |

|

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade |

Australian passports are processed efficientlya |

Travel document processing efficiency is greater than or equal to 90% of the agreed benchmark |

115.8% (Met) |

|

Department of Home Affairs |

Delivery of the Migration and Citizenship Programs contributes to economic prosperity and aligns to national interestsa |

Average number of finalisations per Full Time Equivalent (FTE) visa processing officers increases across both permanent and temporary visa caseloads |

176.07 applications finalised per FTE per month (Met) |

|

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations |

Investment per employment outcome |

$3,500 or lower per employment outcome |

$3575 per employment outcome (Not met) |

Note a: These measures have multiple targets. The targets in the table are those that address entity efficiency.

Source: ANAO analysis of entities’ annual performance statements.

1.34 The above measures represent six out of the 449 measures (1 per cent) reported across the 21 audited entities. As the ANAO has observed in previous years, measures of efficiency are rare in entities’ performance statements. The majority of entities audited by the ANAO in 2024–25 did not report any efficiency measures or efficiency targets.

1.35 Several entities reported proxy measures of efficiency, usually in the form of timeliness measures. These accounted for seven per cent of all measures — 31 of 449 measures. The proxy efficiency measures related to the timeliness of a process to produce an output (such as answering a call or processing a claim); they do not assess the inputs used to produce that output. Timeliness measures only show how quickly activities are completed, but, on their own, do not assess how efficiently resources are used to achieve results.

1.36 The lack of genuine efficiency measures suggests a potential absence of efficiency measurement in the public sector. What gets measured gets done — including efficiency measures can help drive efficiency and productivity improvements in the public sector. Entities should consider opportunities to assess efficiency deliberately. Doing so supports proper use and management of public resources and show greater accountability and transparency in how taxpayer funds are used.

1.37 For an entity, efficiency can act as a bridge between financial stewardship and program and service outcomes: even effective services may not represent good public value if they consume excessive resources. Measuring efficiency can ensure that effectiveness is achieved at an acceptable cost.

1.38 Focusing too heavily on efficiency measures in the public sector carries risks because government services often have complex objectives that extend beyond producing outputs at the lowest cost. A narrow focus on efficiency may inadvertently lead entities to prioritise volume over quality, reduce services in ways that disadvantage vulnerable groups, or create incentives to avoid difficult or high-need clients who require more resources. In some areas, an overemphasis on efficiency may undermine quality, outcomes or long-term impact by encouraging short-term cost savings at the expense of meaningful results.

1.39 Linking financial and non-financial information and reporting a broad mix of measures to complement efficiency measures, such as effectiveness and outcome measures, can help to address these risks by providing a more balanced view of performance.

Linking performance results and financial information

1.40 Users of an entity’s annual performance statements can find it difficult to determine how well the entity has performed in relation to its budget. It is often difficult to evaluate how effectively public money has been used by an entity to achieve intended outcomes, as the link between appropriations, expenditure, key activities and results is often not clear.

1.41 Integrating financial and non-financial performance information can provide information on value-for-money from spending and allow for a richer, more balanced understanding of performance. Linking the two helps users understand how resources are being used relative to what is being achieved, particularly if a precise efficiency ratio cannot be calculated. For example, knowing how much funding went into a key activity or performance measure, alongside information about outputs, service quality, customer satisfaction or outcomes, provides valuable insight into whether that function is delivering value to the public. This also supports a more strategic and citizen-centred view of performance. The combined view can help identify broader patterns that might not be visible from a more specific efficiency measure.

1.42 It can also support better decision-making and strategic planning in entities. When financial information is paired with non-financial performance information, senior leaders can identify where resources are producing meaningful impact and where adjustments may be needed.

1.43 Improving links between financial and non-financial performance information may further inform assessments of public sector productivity, noting that the treatment and measurement of public service productivity has long been known to raise difficult but important issues.25

1.44 Table 1.8 shows the kind of performance information that could be presented in performance statements, when financial and non-financial information is brought together. ANAO analysis and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) performance statements indicate that DVA has not met most of its targets under Outcome 1, and its performance metrics have declined over time. The addition of financial information from the Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS) provides additional context, that the decline in performance has occurred against a background of increases of $124 million in departmental funding and 870 additional full-time equivalent staff between 2022–23 and 2024–25.

1.45 Importantly, DVA’s performance statements provide explanations and insights into the factors influencing its results, such as a rise in both the number and complexity of claims over this period.26

Table 1.8: Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Outcome 1: performance, budget, and staffing

|

Reporting year |

Number of targets per APS |

Number of targets met per APS |

Total departmental budget per PBS ($m) |

Budgeted average staffing level per PBS |

|

2022–23 |

30 |

11a |

348b |

1,445b |

|

2023–24 |

30 |

9 |

445 |

2,006 |

|

2024–25 |

30 |

8 |

472 |

2,315 |

Note a: This count is reflective of updated results presented in the 2023–24 performance statements, that related to the 2022–23 period.

Note b: These figures are as presented in the March 2022–23 Portfolio Budget Statements. Following the 21 May 2022 federal election, the October 2022–23 Portfolio Budget Statements presented a total departmental budget of $436 million and a budgeted average staffing level of 1,818.

Source: ANAO analysis of DVA’s annual performance statements and portfolio budget statements (PBS).

1.46 Table 1.8 was created by the ANAO from disclosures in the PBS and performance statements. In practice, the financial data in the PBS is typically not directly reflected in performance information in performance statements. Key activities and their performance measures cannot always be directly linked to funding or staffing, because an entity’s PBS rarely presents financial information to enable one-to-one comparisons. This limits analysis of efficiency, value for money and return-on-investment.

1.47 There is clear benefit for the Parliament and the public if entities disclose the relationship between results achieved and the allocation and expenditure of resources in their performance statements. Even without formal efficiency measures, linking financial and non-financial information enhances transparency and improves judgments about productivity and performance. It also promotes prudent stewardship of public resources and helps ensure public funds are used effectively to achieve outcomes and impact.

Opportunity for improvement

1.48 Accountability would be strengthened if entity resource information presented in portfolio budget statements could be linked to key activities or measures in performance statements. There is scope for the Department of Finance to issue guidance on this topic.

Measuring outcomes and impact

1.49 Many of the challenges confronting the public sector are long-term or intergenerational in nature. If entities are to anticipate and successfully respond to these challenges, they need to be able to measure and assess their performance by considering both immediate outcomes and sustained, long-term results.

1.50 Entities should look for ways to directly measure their purposes and outcomes, rather than primarily focusing only on measuring their activities and outputs, if they are to improve their impact and demonstrate effective stewardship of public resources. Across the 21 audited entities outcomes and impact are less frequently measured than outputs and activities.

1.51 Effectiveness measures have the potential to indicate whether outcomes are being achieved.27 However, audit experience shows that most effectiveness measures reported by entities are not specifically designed for this purpose. Many focus on individual programs, policies, or activities and do not capture the achievement of longer-term strategic outcomes.

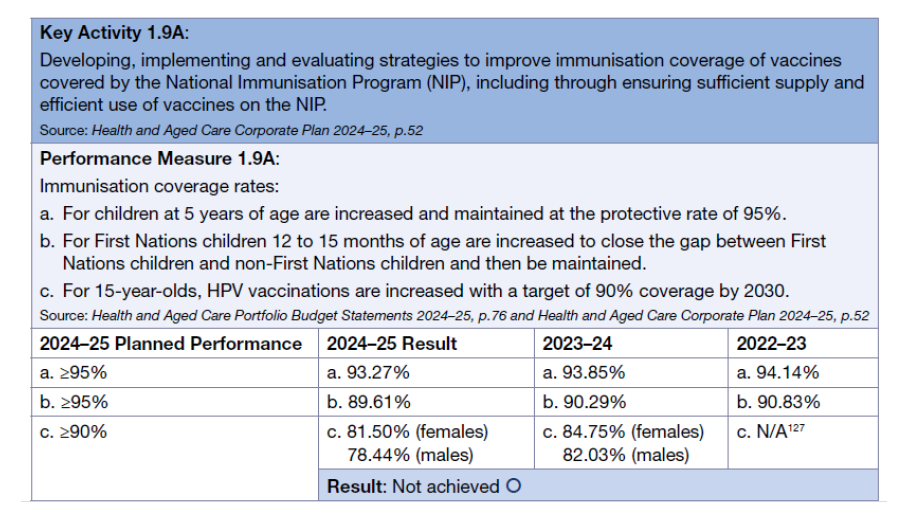

1.52 One example of an outcome-focused effectiveness measure is the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water’s performance measure CCE01, Australia’s emissions and projected emissions are on track to meet legislated outcomes. The performance result reflects the outcomes of various government and non-government initiatives and approaches to reduce emissions.

1.53 Several entities in 2024–25 have included information on impact and outcomes in the narrative and analysis in their performance statements. For example, the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts, uses ‘spotlight’ sections to demonstrate how performance results of output measures contributes to program outcomes. The department’s measure 2 describes whether milestone claims for payments on Infrastructure Investment Program projects have been assessed, with accurate and complete claims authorised for payment. A ‘spotlight’ beneath this measure highlights one of the Program’s projects, the Bunbury Outer Ring Road Project. It outlines the project’s design, budget, and in-year milestones, as well as the benefits of the project to the outcomes of road safety, travel time, and local employment.

1.54 In addition, as shown below, the Department of Health, Disability and Ageing has included narrative in its performance statements regarding the desired impact of the Immunisation program.

|

Case study Department of Health, Disability and Ageing — Program 1.9 Immunisation |

|

The program’s impact is realised through increased coverage, which in turn reduces the incidence and burden of vaccine-preventable diseases. This relationship is well established: as coverage improves, rates of disease, hospitalisation and death decline. According to the AIHW 2019 report ‘The burden of vaccine preventable diseases in Australia’, studies showed the rate of vaccine-preventable burden decreased by 31% between 2005 and 2015. 124 This reduction occurred where vaccines were added to, or eligibility was extended under the NIP such as human papillomavirus (HPV), pneumococcal disease and rotavirus. This reinforces the program’s critical role in protecting individual and community health. Source: The Department of Health, Disability and Ageing 2024–25 Annual Report, page 84 |

Entities’ performance and people’s wellbeing

1.55 The Australian Government has developed a national wellbeing framework — ‘Measuring What Matters’ (MWM) — which aims to measure what Australians value for their wellbeing and track progress over time. The purpose of the MWM framework is to provide information useful in guiding national public policy to promote and improve the wellbeing of people in Australia.28 There are 50 indicators, grouped under five themes: healthy, secure, sustainable, cohesive and prosperous.

1.56 At this stage, there is limited alignment between the MWM Framework and entity performance statements. Only a few MWM indicators are reflected in performance measures in audited entities’ 2024–25 annual performance statements.29 There would be merit in entities considering whether annual performance statements could map key activities to the five wellbeing themes or align MWM indicators with corporate plans and performance statements where relevant. This could help to bring a focus to long-term or intergenerational issues that have been deemed important for measuring national progress. The Department of Veterans’ Affairs provides an example, in seeking to measure veteran wellbeing. It has introduced a dedicated wellbeing performance measure to consider how well clients perceive they are supported by the department’s services across various aspects of their lives. The intent is to enable the department to take a more holistic view of client outcomes, beyond transactional service delivery.30

2. Assessing performance requires meaningful information

Introduction

2.1 An object of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) is for the Commonwealth and Commonwealth entities to provide meaningful information to the Parliament and the public. The revised Explanatory Memorandum to the PGPA Bill (that led to the PGPA Act) explained the context for meaningful information:

for the Parliament to properly fulfil its oversight function, performance information is crucial to assessing whether policy goals are being achieved. Performance information also shows how effectively the public sector has performed. The quality of information is more important than the quantity.31

2.2 In seeking to ensure meaningful information is presented to the Parliament, the PGPA Act introduced the requirement for entities to prepare a corporate plan and annual performance statements. It also makes provision for the performance statements to be audited by the Auditor-General, following a request from the Finance Minister or the responsible Minister.

2.3 The corporate plan and performance statements, together with the Portfolio Budget Statements32, provide an integrated view of what the entity aims to achieve, how it proposes to achieve it using public resources, what progress it has made and the outcomes it has achieved. The requirement for entities to prepare these documents acknowledges that public sector performance is more than financial33 and can often be a ‘blurry, elusive concept’34. Requiring entities to report against the expectations set out in a corporate plan promotes a strategic focus on entity purposes and improves accountability and transparency about how public resources are used and what results are achieved.

2.4 The 2024–25 audit program shows that entities have improved their ability to produce performance statements that meet the minimum legal requirements of the PGPA Act. While this progress is recognised, audit work shows that compliance with minimum legal requirements does not necessarily produce information that is appropriate and meaningful for the entity or for users assessing the entity’s performance in achieving its purposes.35 Entities continue to default to easily quantifiable (and auditable) performance measures, even when these do not accurately reflect the impact of their activities.

2.5 Inadequate performance information presents challenges not only for Parliament, but also for the government and accountable authorities. Parliament and the public require meaningful performance information to assess whether entities are delivering on their purposes and using public resources efficiently and effectively. Decision-makers, as stewards of public resources, require clarity to make informed decisions.

What is ‘meaningful information’?

2.6 The Department of Finance states that ‘Performance planning and reporting should [… provide] meaningful performance information’.36 However, ‘meaningful information’ is not defined for the purposes of the Commonwealth Performance Framework. It is therefore a subjective and gradable concept under current performance reporting arrangements. What is meaningful information for one reader may be less meaningful for another. Information could be described as ‘meaningful’, while recognising that it could be more meaningful.

2.7 Factors identified through the performance statements audit program that suggest information is meaningful include that it:

- complies with the requirements of the PGPA Rule;

- is complete and measures and assesses what matters the most to users, not just what is easy to measure37;

- relates directly or clearly links38 to the entity’s purposes or key activities — that is, it reflects both what an entity can directly control and where it contributes to results;

- goes beyond simply tracking activities or outputs to capture outcomes and, where possible, contributions to longer term impact;

- provides a clear, accurate and balanced presentation of the entity’s performance in achieving its purposes;

- is useful for accountability, improvement and decision-making purposes;

- is aligned with how the entity measures and assesses its performance for internal management and accountability purposes; and

- meets user needs as it is the type of performance information sought by key stakeholders, such as Parliament and the public, reflecting their interests and perspectives.

2.8 Clarity of the Commonwealth Performance Framework would assist entities to better understand the qualities that make annual performance statements stakeholder focussed and meaningful.

‘Meaningful information’ and performance statements audits

2.9 The New Zealand Accounting Standards Board (NZASB) has issued a Standard39 for the reporting of service performance information. As noted by the NZASB, the Standard establishes high-level requirements because, among other reasons:

(c) It provides flexibility for entities to determine how best to ‘tell their story’ in an appropriate and meaningful way.40

2.10 The NZASB opted for a high level, principles-based approach to provide sufficient flexibility for entities to ‘tell their story’ in a way that is meaningful for them and their users, to avoid some of the difficulties that could arise with a more prescriptive approach and to avoid imposing unnecessary costs.41

2.11 There is no equivalent Australian Standard42 to the NZASB Standard for service performance information. Rather, the Commonwealth Performance Framework, including the PGPA Act and Rule and Finance Resource Management Guides, operates as one for Commonwealth entities and has similar flexibility as in New Zealand. In addition, the ANAO’s audit criteria regarding completeness and fair presentation aim to promote reporting beyond minimum compliance with the Commonwealth Performance Framework requirements, enabling auditors to assess and evaluate whether performance statements meet the object of the PGPA Act for entities to prepare meaningful information to the Parliament and the public.43

2.12 Figure 2.1 conceptualises the key building blocks for an entity to provide appropriate and meaningful performance information to the Parliament and the public. An entity-wide performance framework is a key tool for strategic planning and developing an entity’s corporate plan. It is also what drives behaviour and business planning in an entity.44 An entity’s performance framework ensures that the key elements of meaningful information in performance statements are met:

- completeness — of purposes and key activities;

- appropriateness — of performance measures and targets; and

- clear, comprehensive and insightful narrative and analysis.

Figure 2.1: The building blocks for ‘meaningful information’

Source: ANAO

Completeness of purposes and key activities

2.13 Clearly defining an entity’s purposes45 is fundamental for reporting meaningful performance information. ‘Purposes’ should consider the entity’s outcomes and programs in its Portfolio Budget Statements, its enabling legislation and statutory obligations, and its Administrative Arrangements Order. The Department of Finance advises that an entity’s purpose statement in its corporate plan should be sufficiently specific to allow for meaningful measurement and assessment, and relevant to reflect medium to long term goals.46

2.14 Key activities represent the main things the entity does to deliver on its purposes. They form the link between purpose, performance and accountability. By clearly identifying what activities are most critical to achieving its purpose, an entity can focus resources efficiently, set appropriate performance measures and targets, and communicate its achievements and impact more clearly.

2.15 Audits show that there is benefit in entities establishing a systematic approach for identifying their key activities. Business plans, and the entity’s organisational structure, can be a good starting point. Other reference points may include the value of appropriations for programs and sub-programs, whether the initiative is a priority of government, and whether it is of public or parliamentary interest. When key activities are overlooked, important performance information may be left out of performance statements.

2.16 Most entities in the 2024–25 performance statements audit program have either an established basis to identify their purposes and key activities or have plans to develop this basis. An entity that applies a clear approach to set and review its purposes and key activities has a platform from which to develop meaningful performance information.

Reporting on statutory office holders within entities

2.17 Entities should pay particular attention to reporting on those functions that relate to statutory office holders that are not a listed entity 47 under the PGPA Act in their own right but are supported financially and administratively by a portfolio department or a listed entity. The 2024–25 audits identified a potential gap regarding whether, and in what manner, PGPA Act entities should report on the functions of such statutory authorities or office holders. This is particularly relevant for measuring and assessing the achievement of the entity’s purposes, given that many such authorities or office holders have separate reporting obligations outside the PGPA Act, while the accountable authority of the PGPA Act entity remains responsible for performance reporting under the Act.

2.18 The ANAO observed that entities had different approaches to reporting on the role of these statutory authorities and office holders, with some reporting on these functions in their performance statements and others not, without a clear rationale. One example of clarity is the Australian Taxation Office (ATO), which expressly includes the Tax Practitioner’s Board (TPB) and the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC) in the description of the ATO as a listed entity in the PGPA Rule.48

Opportunity for improvement

2.19 The Department of Finance could provide guidance for entities to report, in their performance statements, on the functions of statutory authorities and office holders that are not a separate PGPA Act entity and are financially and administratively supported within the entity, recognising that the accountable authority remains responsible for performance reporting under the PGPA Act.

Materiality is maturing

2.20 The information needs of Parliament, government and the public are diverse and wide-ranging. Performance statements are not intended to include every piece of information needed by all users for accountability or decision-making.

2.21 Materiality focuses on what is important to users when relying on the performance statements to make informed decisions. It guides auditors to identify the areas of performance information where errors or omissions could reasonably influence users’ assessments or decisions. Materiality and the assessment of risk factors, such as biased performance measures, incomplete reporting, or unreliable data, assist the auditor to focus their work on measures, disclosures, and systems that are more likely to result in a material misstatement.

2.22 The concept of materiality helps ensure that performance statements remain focused, relevant, and meaningful by guiding entities to prioritise performance information that is most relevant to stakeholders’ needs and decision-making. It enables entities to strike a balance between completeness and conciseness, helping them to avoid overloading reports with excessive or low-value information that obscures key messages. Where appropriate, entities can provide links to other relevant information for readers seeking additional detail.

2.23 When the performance statements audit program commenced in 2021–22, many entities did not have an established materiality policy or if one had been established, the primary focus was on the financial scale of a function. Notably, the 2024–25 audits found that most entities had a defined materiality policy in place that looked at a wider range of factors to determine what is material. In addition to financial factors, materiality policies also consider matters of Parliamentary attention, government priorities, and areas of public interest.

2.24 Figure 2.2 shows that entities are subject to a broad set of accountability and performance related requirements, which in many instances require the production of performance information.49 Unlike annual performance statements, most of this information is not subject to systematic assurance by the ANAO and not every report is fully scrutinised by the Parliament.

2.25 The current landscape of requirements has accumulated through incremental changes over many decades. This build-up appears to have resulted in increased reporting by entities and has made it difficult to determine how the requirements relate to each other. As a result, it is sometimes unclear if the reporting system enables Parliament to effectively hold the Executive accountable for its performance.

2.26 Ensuring that annual performance statements contain all ‘material’ information can bring a degree of coherence to the reporting landscape. Although performance statements might not be of equal relevance to all users, they can serve as a core accountability document, providing the starting point from which to explore and question for more specific purposes. For example, the ANAO encourages entities to include references to other documents and reports, where appropriate, rather than repeating content across multiple sources.50

Figure 2.2: Relationship of performance statements audits to government policies and frameworks

Source: ANAO.

2.27 The ANAO has found that entities already produce relevant and useful information, both for day-to-day management and governance purposes as well as to fulfil accountability obligations. Consequently, many entities will not generally need to collect and design information specifically for performance statements. Instead, they should first seek to determine what existing performance information can be used to tell a meaningful story of the entity’s performance in achieving its purposes.

Appropriateness of measures and targets

2.28 Performance information can be either quantitative or qualitative. While quantitative measures can at times offer advantages, including precision, in many cases qualitative approaches may be preferable — rather than measures this could include a summary of progress and stakeholder perceptions of what has been achieved. This recognises that performance measurement and reporting in the public sector is about increasing understanding and knowledge rather than seeking precision through numbers alone.

2.29 Logic models show how government policies, programs or other interventions are intended to work by illustrating causal links between inputs, activities, outputs and outcomes. They can assist entities to identify the results they aim to achieve and determine what aspects are within their direct control — and assist in establishing appropriate measures for both. Effective use of logic models demonstrates that the entity has thoughtfully considered the selection of its performance measures. Only a few entities in the 2024–25 performance statements audit program had developed and applied logic models systematically to establish their performance measures.

2.30 The 2024–25 audit results highlight a number of factors that support entity compliance with the requirements of s16EA of the PGPA Rule.51

- Providing context on why a particular measure was chosen can help readers understand its relevance.

- Performance measures should be clear and understandable, making them easy to interpret by everyone who uses them. It is important to avoid unnecessary ambiguity, complexity or technical jargon, which can make it harder for Parliament and the public to understand what the entity is trying to achieve and whether it is succeeding.

- Given that entity operations are complex, multifaceted and influenced by many factors, a single performance measure will rarely fully measure an entity’s performance in achieving its purposes. Similarly, where key activities are broadly defined, a single measure may not adequately capture all the important aspects of performance.

- In assessing whether performance measures provide adequate coverage of key activities or purposes, entities should select only those measures needed to measure and assess performance. They should avoid focussing too heavily on the quantity of measures. Too many measures can lead to information overload and obscure what truly matters.

- Among the 21 audited entities, there was significant variability in the approach to reporting performance measures against key activities. The National Disability Insurance Agency and the Department of Industry, Science and Resources both report, on average, six measures per key activity. The Department of Health, Disability and Ageing reports, on average, one measure per key activity.

2.31 An identified risk to meaningful reporting is the PGPA Rule requirement for performance measures to relate directly to an entity’s purposes or key activities. Although this requirement promotes relevance and accountability, it may also narrow the focus of an entity’s performance assessment if interpreted as requiring ‘direct control’. A narrow interpretation may lead entities to overlook indirect outcomes and long-term impacts. Additionally, entities may prioritise quantitative measures over qualitative ones, focusing on what is easy to measure rather than what is meaningful.

2.32 The 2024–25 audits identified numerous measures indicative of this risk, including those reporting on dollars spent on service provision or number of grants administered. On their own, such measures have limited value in reporting whether entities are operating efficiently and effectively in achieving their purposes, thereby delivering public value. Complementing such measures with additional measures or narrative that report on outcomes and impact would provide a more meaningful picture of performance.

2.33 As performance reporting matures, entities are increasingly complementing their purpose and key activity aligned measures with measures that capture long-term outcomes and impact. Alternatively, they include narrative and analysis that reports on the broader dimensions of performance as reflected in the following example from the Department of Health, Disability and Ageing.

|

Case study Department of Health, Disability and Ageing — Program 1.9 Immunisation |

Source: Department of Health, Disability and Ageing 2024–25 Annual Report, page 85 The Department of Health, Disability and Ageing (DHDA) developed measures related to coverage rates that it does not directly control. It also included in its narrative the aspects of performance that it does control and that are directly related to the key activity. That is:

Source: Department of Health, Disability and Ageing 2024–25 Annual Report, page 86 |

Measure what matters the most

2.34 The effectiveness of many Australian government policies, programs and services can be difficult to measure, particularly in a system of accountability that is focussed on individual entities. Performance can be influenced by many factors beyond the impact of an entity’s activities, some of which may only be evident over long periods of time. Factors such as other government actions or programs, economic conditions, demographic changes, social trends and partner entity activities can all influence outcomes.

2.35 Causality is difficult to establish and can create challenges for preparers of performance statements and auditors. It can affect the reliability, credibility, and usefulness of performance information. Performance statements may unintentionally (or strategically) oversimplify cause-and-effect links to make the entity’s performance appear stronger or more direct. This can lead to conclusions that can be misrepresented or present unrealistic expectations about the effectiveness of interventions, and what policies or programs can achieve. For example, the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations might report improved job placement rates, but these could also reflect broader economic growth rather than the entity’s specific interventions.