Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Australian Antarctic Program

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Australia has strong and long-standing strategic and scientific interests in the Antarctic region. The Australian Antarctic Program (the program) encompasses Australia’s activities in Antarctica, including scientific research and infrastructure works.

- The Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) in the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (the department) manages the delivery of the program.

- This audit provides the Parliament with assurance on whether the department is effectively managing the delivery of the program to achieve program outcomes.

Key facts

- The department’s activities in Antarctica are guided by Australia’s national interests as outlined in the 2016 Australian Antarctic Strategy and 20 Year Action Plan.

- The 2024–25 Season Plan outlined three key science and three key non-science deliverables for the season.

What did we find?

- The department is partly effective in managing the delivery of the program to achieve program outcomes.

- The program is supported by partly appropriate governance and strategic planning arrangements.

- The department is partly effective in managing the delivery of the program. Lack of a clear project management framework has led to varied and inconsistent arrangements being established for project-level oversight, risk management, reporting and evaluation.

- The department is largely effective in evaluating, monitoring and reporting on achievement of program outcomes.

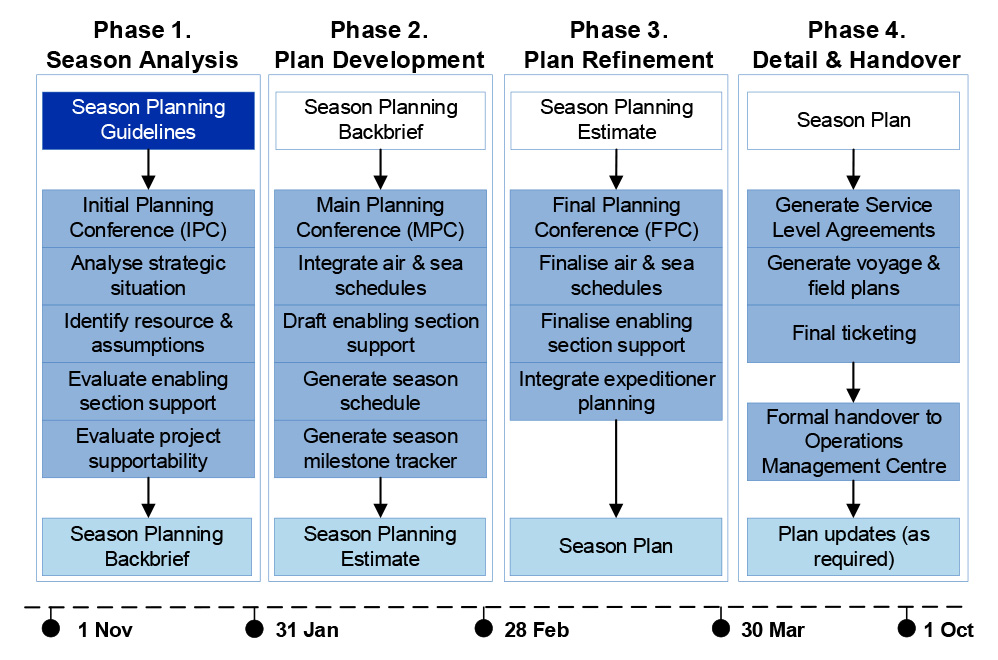

What did we recommend?

- There were eight recommendations to the department, aimed at improving: risk management; workforce planning; project management; and evaluation activities.

- The department agreed to all eight recommendations.

$373 m

funding allocated to the Australian Antarctic Program in 2024–25.

5

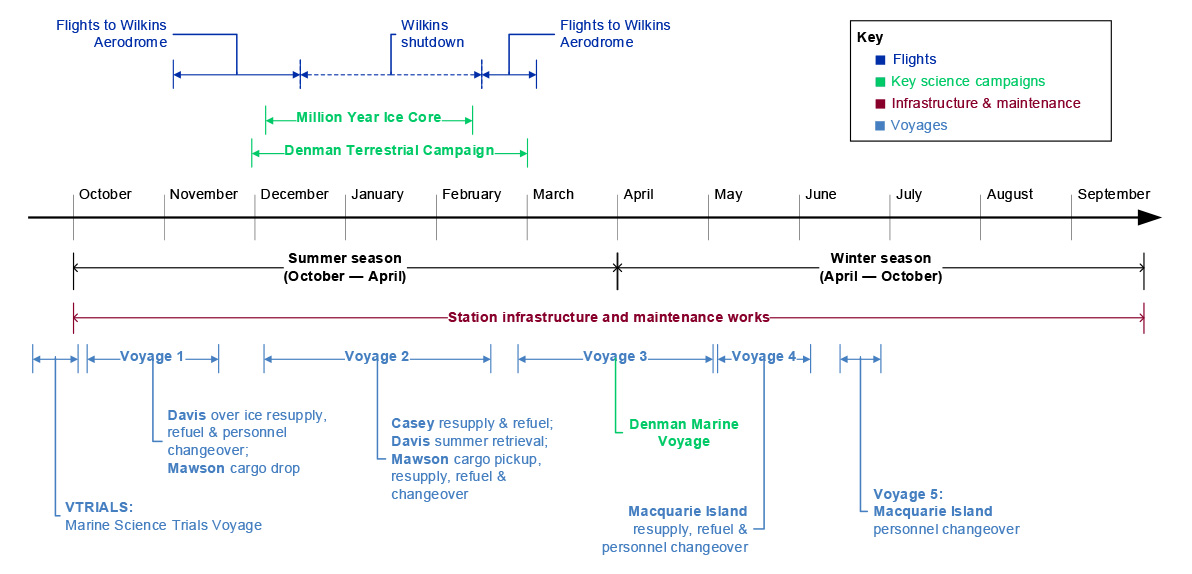

voyages were undertaken in the 2024–25 season, including RSV Nuyina’s first dedicated marine science voyage (Voyage 3).

436

expeditioners were contracted to deliver the activities in the 2024–25 season.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Antarctica covers over 13 million square kilometres and is the highest, driest, windiest and coldest continent in the world. Australia aims to exercise leadership and influence in the international forums for the governance and management of the Antarctic region. The Australian Antarctic Territory covers 5.8 million square kilometres and comprises 42 per cent of the total area of Antarctica.

2. Australia’s activities in Antarctica, from scientific research through to logistics and infrastructure works, are coordinated through the Australian Antarctic Program (the program).1 The Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) in the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (the department) is responsible for managing the delivery of the program. The AAD is funded under the department’s Outcome 3:

Antarctica: Advance Australia’s environmental, scientific, strategic and economic interests in the Antarctic region by protecting, researching and administering in the region, including through international engagement.

3. The AAD’s activities are guided by Australia’s national interests in Antarctica as outlined in the 2016 Australian Antarctic Strategy and 20 Year Action Plan. Australia’s national interests are to:

- maintain Antarctica’s freedom from strategic and/or political confrontation;

- preserve our sovereignty over the Australian Antarctic Territory, including our sovereign rights over adjacent offshore areas;

- support a strong and effective Antarctic Treaty system;

- conduct world-class scientific research consistent with national priorities;

- protect the Antarctic environment, having regard to its special qualities and effects on our region;

- be informed about and able to influence developments in a region geographically proximate to Australia; and

- foster economic opportunities arising from Antarctica and the Southern Ocean, consistent with our Antarctic Treaty system obligations, including the ban on mining and oil drilling.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. Australia has strong and long-standing strategic and scientific interests in the Antarctic region. The March 2022–23 Federal Budget announced over $800 million to strengthen Australia’s presence in Antarctica. The 2023–24 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook and 2024–25 Federal Budget both provided additional funding to continue delivery of the program and to expand Australia’s international scientific activities in the region.

5. The program is of parliamentary interest. In May 2024, the Senate Environment and Communications References Committee recommended that the ANAO conduct an audit into the effectiveness of the department’s management of Australia’s Antarctic presence.

6. This audit provides the Parliament with assurance on whether the department is effectively managing the delivery of the program to achieve program outcomes.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The objective of the audit was to assess whether the department is effectively managing the delivery of the program to achieve program outcomes.

8. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Is the Australian Antarctic Program supported by appropriate governance and strategic planning arrangements?

- Is the department effectively managing the delivery of the Australian Antarctic Program?

- Is the department effectively evaluating, monitoring and reporting on its activities to determine whether the desired outcomes of the Australian Antarctic Program are being achieved?

Conclusion

9. The department is partly effective in managing the delivery of the program to achieve program outcomes. While improvements in governance and planning have been made since 2023 through establishing new arrangements, there is a need to further strengthen oversight of risk management, long-term workforce planning, project delivery, and evaluation of activities to more clearly demonstrate the achievement of program outcomes.

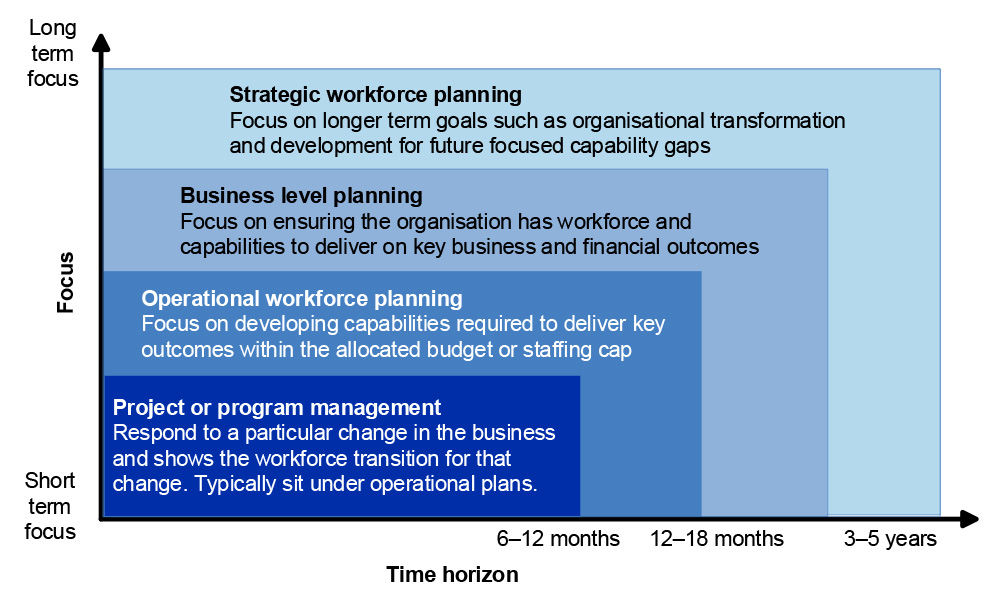

10. The program is supported by partly appropriate governance and strategic planning arrangements. New governance and strategic planning arrangements were established in 2023 and 2024 to support the delivery of the program. Ongoing effort is required to embed these new arrangements into the AAD’s operations given the high-risk operating environment. Greater clarity is needed to guide the AAD’s risk management activities, including stronger oversight over the management of severe and fatal risks. Workforce planning is primarily focused on the short term rather than the long term. It is not integrated into broader planning arrangements. The department does not effectively monitor expeditioners’ compliance with mandatory training.

11. The department is partly effective in managing the delivery of the program. A new season planning process was introduced in 2023 for the 2024–25 season. The three key science deliverables for the 2024–25 season were largely delivered in accordance with the season plan. However, lack of a clear project management framework has led to varied and inconsistent arrangements being established for project-level oversight, risk management, and reporting. There is a need for the department to improve planning for the AAD’s capital projects and consider whether its systems are fit for purpose to enable effective tracking of the AAD’s infrastructure and maintenance works. While appropriate arrangements are in place to monitor season activities, the role of After Activity Reviews has not been clearly established and there are no clear processes to evaluate the overall success of the season in achieving its objectives.

12. The department is largely effective in evaluating, monitoring and reporting on whether program outcomes are being achieved. The Australian Antarctic Strategy and 20 Year Action Plan (strategy and action plan) outlines the objectives and outcomes to be pursued through the program. Although the department undertakes five-yearly reviews of its progress in implementing the strategy and action plan, it has not established arrangements to monitor progress in between these reviews. The department established three performance measures relating to its activities in Antarctica and in 2024–25 reported that it had achieved the targets set for all three. It undertakes public and non-public reporting on the program and its progress in implementing the strategy and action plan, and a project is planned to further improve its performance reporting.

Supporting findings

Governance and strategic planning

13. New oversight arrangements were established in 2023 and 2024 to support the delivery of the program. These governance structures require ongoing effort to grow their maturity as they are embedded into the AAD’s operations. Risk management activities are occurring, but they are not guided by a clear risk strategy tailored to the AAD’s operational context, which heightens the likelihood that critical risks may not be properly identified, assessed, and mitigated. The AAD’s severe and fatal risks are escalated and discussed in governance forums. However, there is a need for stronger oversight over these risks, including clearer articulation of risk controls and treatments, and informed acceptance of the risks by senior management, in order for the department to effectively demonstrate its compliance with WHS obligations. (see paragraphs 2.2 to 2.61)

14. New strategic planning arrangements were introduced in 2023 and 2024 to help deliver the priorities outlined in the strategy and action plan. These arrangements, once fully embedded, have the potential to improve the AAD’s strategic planning to determine, document and operationalise program priorities. Development and finalisation of the implementation plan for the Australian Antarctic Science Decadal Strategy and the infrastructure masterplans may help the AAD to more clearly articulate the science and non-science priorities for the Australian Antarctic Program and align them to its planned activities. (see paragraphs 2.62 to 2.94)

15. The AAD does not have appropriate workforce planning arrangements to support the delivery of the program. Its consideration of workforce needs is focused on immediate seasonal recruitment and allocation of tickets to expeditioners. Training is provided to expeditioners based on their role, station, departure date and mode of transport. Expeditioner compliance with mandatory training requirements is not effectively monitored, and the department has limited assurance over whether the expeditioners are working on tasks they are not adequately trained for. (see paragraphs 2.95 to 2.117)

2024–25 season delivery

16. A new season planning process was introduced in 2023 for the 2024–25 season. There is clear procedure and guidance to support the season planning process. Season planning is informed by consideration of risk, resources, logistics, and alignment to strategic priorities. The season planning process does not include a structured approach to incorporating lessons learned from previous seasons. Season risks rated ‘severe’ were not escalated in accordance with requirements, reducing the effectiveness of risk management, oversight and decision-making. (see paragraphs 3.2 to 3.34)

17. Lack of a clear project management framework has led to varied and inconsistent arrangements being established for project-level planning, oversight, risk management, and reporting. A historical pattern of significant variations in capital budget indicates improved planning for capital projects is needed. Ongoing capital infrastructure works and maintenance activities are managed and tracked via the AAD’s asset maintenance system, Maximo, which has issues with accuracy and completeness of information. There is an opportunity for the department to consider whether its systems are fit for purpose to enable effective planning, tracking and assurance over the delivery of its capital projects. (see paragraphs 3.35 to 3.93)

18. The arrangements in place to monitor and evaluate seasonal activities are mixed. There are appropriate arrangements to monitor seasonal activities. Arrangements are in place to evaluate some activities, but the role of After Activity Reviews has not been clearly established and the evaluation reports do not clearly articulate whether the desired objectives were achieved. Available reporting indicates that the Denman Marine Voyage and Denman Terrestrial Campaign took place as scheduled and supported all planned science projects. The Million Year Ice Core project was delayed but delivered the majority of planned activities. The department does not have an established process in place to evaluate the overall success of the season in achieving its objectives. (see paragraphs 3.94 to 3.112)

Evaluation, monitoring and reporting

19. The strategy and action plan outlines the objectives and outcomes to be pursued through the program. The department undertook a five-year review of the strategy and action plan in 2021 and has commenced planning for a ten-year review in 2026. The department does not monitor implementation of the commitments in the strategy and action plan in between the five-yearly reviews. (see paragraphs 4.2 to 4.17)

20. The department undertakes public and non-public reporting on the program and its progress in implementing the strategy and action plan. The department has three performance measures relating to its activities in Antarctica, which are compliant with the requirements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014. It reported that in 2024–25 it achieved the targets set under each measure. The AAD is planning to undertake a project to improve its performance reporting and may benefit from considering whether it can better capture the breadth of its activities in Antarctica as described in its outcome. (see paragraphs 4.18 to 4.28)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.32

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water implement a risk strategy and supporting resources for the AAD, outlining how its Enterprise Risk Management Framework should be operationalised and risks identified, escalated, and managed within the division’s operational context.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.60

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, in managing the AAD’s fatal risks, establish arrangements to ensure:

- its safety standards and standard operating procedures are developed, reviewed and updated in a timely manner, to prevent risks of staff operating under unwritten or potentially outdated instructions;

- it is clear what controls are in place for each fatal risk and how their efficacy was considered in self-assessments;

- its governance bodies, in their reviews of the fatal risk register, clearly indicate whether any fatal risks require additional treatments, or have been discussed and accepted as being adequately controlled without the need for further treatments; and

- these processes and decisions are clearly documented in accordance with the department’s record-keeping and WHS obligations to demonstrate compliance and support accountability.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.92

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water more clearly align its planned activities with the government’s key commitments, including by:

- developing and finalising the implementation plan for the Australian Antarctic Science Decadal Strategy, and the infrastructure masterplans, in a timely manner, to clearly articulate the science and non-science priorities for the Australian Antarctic Program; and

- clearly documenting its rationale for focusing on certain campaigns and projects as priorities for the relevant seasons in reference to these key strategic documents.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 2.108

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water establish a workforce planning process for the AAD that considers both operational and long-term workforce requirements, linked to an assessment of risks and key capabilities needed to deliver on its objectives.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 2.116

To mitigate the risks arising from training non-compliance, the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water implement arrangements to ensure that:

- expeditioners complete their mandatory training prior to departure, with any exemptions and missed training accurately tracked and recorded; and

- there are controls in place to verify and provide assurance that all expeditioners have completed the required training before they commence their duties.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.42

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water develop a project management framework for the AAD, outlining how projects and multi-project campaigns of different size and complexity should be classified, managed, delivered and reported on.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 3.103

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water establish an approach for the conduct of After Activity Reviews (AARs), including:

- defining the types of activities or deliverables that are required to be evaluated, which should be commensurate with their importance to the delivery of the season;

- outlining how and when to assess and document the achievement of outcomes or objectives of each activity or deliverable being evaluated;

- determining how the AARs should inform whole-of-season evaluation; and

- ensuring appropriate documentation of these arrangements as they are established.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 8

Paragraph 3.110

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water develop a process to: establish clear season objectives at the outset; evaluate the performance of completed seasons against those objectives; and capture and incorporate lessons learned in future planning.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (the department) welcomes the Australian National Audit Office’s audit report on the Australian Antarctic Program and acknowledges the findings of the audit.

The department agrees with all eight of the report’s recommendations and notes that the recommendations build on improvements made by the department to the Program’s administration over the last two years, particularly improvements in governance, expeditioner training, integrated planning, and monitoring and reporting on program outcomes.

The department is committed to ongoing improvement in delivery of the Australian Antarctic Program to ensure it continues to provide a strong platform that delivers on Australia’s national interests in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean, including our administration of the Australian Antarctic Territory, support for critical science, and demonstrating our commitment to and leadership in the Antarctic Treaty system.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

21. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Policy/program implementation

Performance and impact measurement

Governance and risk management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Antarctica covers over 13 million square kilometres and is the highest, driest, windiest and coldest continent in the world. Activities in Antarctica and surrounding seas are governed by four major international agreements which make up the Antarctic Treaty system:

- 1959 Antarctic Treaty;

- 1972 Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals;

- 1980 Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources; and

- 1991 Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (Madrid Protocol).

1.2 The 1959 Antarctic Treaty, which came into force in 1961, establishes that Antarctica should be used exclusively for peaceful purposes, in particular scientific research. The Madrid Protocol, adopted in 1991, designates Antarctica as ‘a natural reserve, devoted to peace and science’, bans mining, and articulates environmental protection responsibilities for signatories.2

Australia in Antarctica

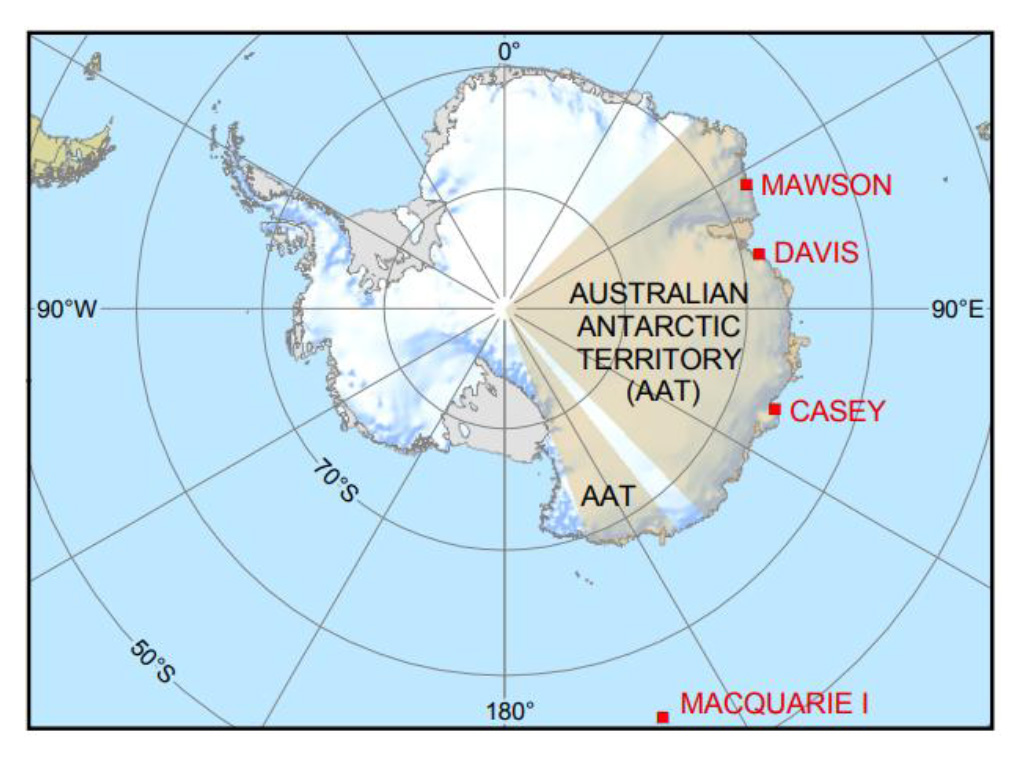

1.3 Australia was one of the 12 original signatories to the Antarctic Treaty and aims to exercise leadership and influence in the international forums for the governance and management of the Antarctic region. The Australian Antarctic Territory covers 5.8 million square kilometres and comprises 42 per cent of the total area of Antarctica, which is nearly 80 per cent of the size of Australia (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Australian Antarctic Territory and permanent stations

Source: Australian Antarctic Data Centre.

Australian Antarctic Program

1.4 Australia’s activities in Antarctica, from scientific research through to logistics and infrastructure works, are coordinated through the Australian Antarctic Program (the program).3 The Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) in the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (the department) is responsible for managing the delivery of the program. The AAD’s work in Antarctica is seasonal, with the bulk of its activities delivered during the summer operating season (October to April).

1.5 The activities of the AAD are funded under the department’s Outcome 3:

Antarctica: Advance Australia’s environmental, scientific, strategic and economic interests in the Antarctic region by protecting, researching and administering in the region, including through international engagement.

1.6 Administered and departmental funding allocated to Outcome 3 over the forward estimates is outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Funding for Outcome 3 ($’000)

|

Financial year |

2024–25 Estimated actual |

2025–26 Forward estimate |

2026–27 Forward estimate |

2027–28 Forward estimate |

2028–29 Forward estimate |

|

Total administered |

5,012 |

5,012 |

5,012 |

5,012 |

5,012 |

|

Total departmental |

368,091 |

387,185 |

357,252 |

367,144 |

374,450 |

|

Total |

373,103 |

392,197 |

362,264 |

372,156 |

379,462 |

Source: 2025–26 Portfolio Budget Statements, p. 62.

1.7 The program is collaborative, with partnerships across government and more than 150 national and international research institutions. Australia also works with other countries’ Antarctic programs to run joint international scientific and logistical operations, and to provide and receive assistance and support.4

Australian Antarctic Strategy and 20 Year Action Plan

1.8 Australia’s national interests in Antarctica are outlined in the 2016 Australian Antarctic Strategy and 20 Year Action Plan (strategy and action plan), which was updated in 2022.5 Along with the department’s Outcome 3, the national interests in the strategy and action plan outline the intended outcomes of the department’s activities in Antarctica. Australia’s national interests are to:

- maintain Antarctica’s freedom from strategic and/or political confrontation;

- preserve our sovereignty over the Australian Antarctic Territory, including our sovereign rights over adjacent offshore areas;

- support a strong and effective Antarctic Treaty system;

- conduct world-class scientific research consistent with national priorities;

- protect the Antarctic environment, having regard to its special qualities and effects on our region;

- be informed about and able to influence developments in a region geographically proximate to Australia; and

- foster economic opportunities arising from Antarctica and the Southern Ocean, consistent with our Antarctic Treaty system obligations, including the ban on mining and oil drilling.

1.9 The 2016 strategy and action plan outlined program objectives and outcomes for year one, year two, year five and years 10 to 20. In the 2022 update, the strategy and action plan provided an overview of achievements for the first five years to 2021 and outlined the priorities and actions to focus on for the next five years to 2026.

Australian Antarctic Science Program

1.10 The Australian Antarctic Science Program operates within the Australian Antarctic Program ‘to deliver world-class scientific research consistent with Australia’s Antarctic science strategic priorities’.6 Australia’s Antarctic science strategic priorities were outlined in the April 2020 Australian Antarctic Science Strategic Plan, which was superseded by the Australian Antarctic Science Decadal Strategy 2025–2035 (decadal strategy) in February 2025. The decadal strategy outlines the highest priority scientific outcomes to advance Australia’s national interests in Antarctica and sub-Antarctic regions, and provides strategic guidance for the development of future research projects.

Previous audits and reviews

1.11 There have been two ANAO performance audits of the program.

- Auditor-General Report No. 22 2015–16 Supporting the Australian Antarctic Program concluded that mature policies and frameworks were in place to support the effective delivery of key program responsibilities, and noted that there was scope for the AAD to regularly review the effectiveness and appropriateness of policies, frameworks and administrative practices for the program.7

- Auditor-General Report No. 45 2016–17 Replacement Antarctic Vessel found that the procurement process for the Antarctic vessel was largely non-competitive, with an outcome that was higher than the cost benchmarks established by the department and significantly greater than chartering costs at the time, and therefore the department could not demonstrate its procurement provided value for money.8

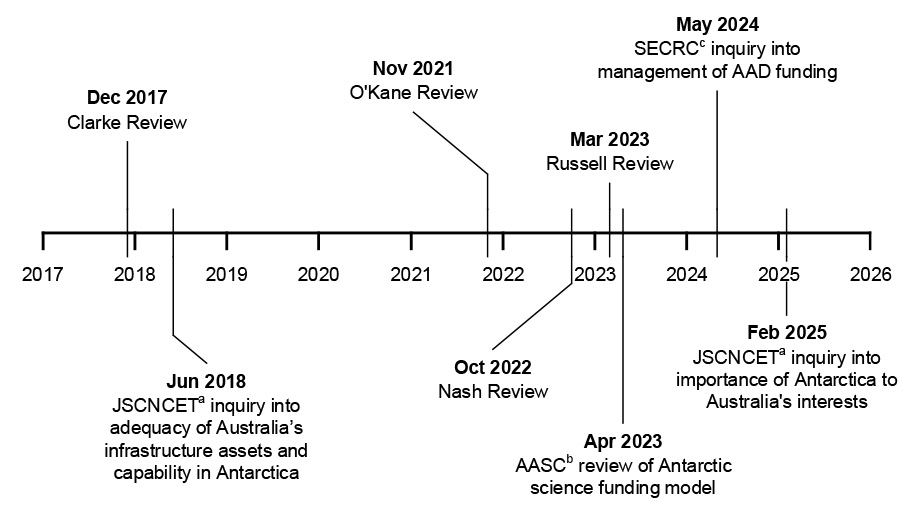

1.12 There have been eight other reviews and inquiries into the AAD and the program since 2017, which are summarised in Figure 1.2 and outlined in further detail in Appendix 3.

Figure 1.2: Timeline of key reviews and inquiries into Australian Antarctic Division and the program

Note a: JSCNCET refers to the Joint Standing Committee on the National Capital and External Territories.

Note b: AASC refers to the Australian Antarctic Science Council.

Note c: SECRC refers to the Senate Environment and Communications References Committee.

Source: ANAO representation of key reviews and inquiries.

1.13 Key findings of the reviews have included: critical challenges in the AAD’s governance and leadership; the impact and limitations of the current funding model; serious issues in workplace culture and the need to improve diversity, inclusion and staff wellbeing; and the need to prioritise and invest in impactful Antarctic science. The March 2023 Independent Review of Workplace Culture and Change at the Australian Antarctic Division (Russell Review) has in particular resulted in significant governance and leadership restructure at the AAD across 2023 and 2024, with much of its cultural reform efforts ongoing.9 The department has commenced a two-year review of progress in implementing the Russell Review’s recommendations.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.14 Australia has strong and long-standing strategic and scientific interests in the Antarctic region. The March 2022–23 Federal Budget announced over $800 million to strengthen Australia’s presence in Antarctica. The 2023–24 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook and 2024–25 Federal Budget both provided additional funding to continue delivery of the program and to expand Australia’s international scientific activities in the region.

1.15 The program is of parliamentary interest. In May 2024, the Senate Environment and Communications References Committee recommended that the ANAO conduct an audit into the effectiveness of the department’s management of Australia’s Antarctic presence.

1.16 This audit provides the Parliament with assurance on whether the department is effectively managing the delivery of the program to achieve program outcomes.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.17 The objective of the audit was to assess whether the department is effectively managing the delivery of the program to achieve program outcomes.

1.18 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Is the Australian Antarctic Program supported by appropriate governance and strategic planning arrangements?

- Is the department effectively managing the delivery of the Australian Antarctic Program?

- Is the department effectively evaluating, monitoring and reporting on its activities to determine whether the desired outcomes of the Australian Antarctic Program are being achieved?

1.19 The audit did not examine: the department’s engagement with international Antarctic forums, organisations and partnering nations; contract management for the icebreaker vessel RSV Nuyina; discharge of regulatory responsibilities in the Australian Antarctic Territory under the Antarctic Treaty (Environment Protection) Act 1980 and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999; projects and activities from prior seasons, except if relevant to the 2024–25 season; and findings and recommendations from previous reviews of the AAD and the program, except to the extent relevant to the matters examined in the audit.

Audit methodology

1.20 The audit methodology included:

- examining entity documentation and data;

- examining the delivery of key projects in the 2024–25 Season Plan, including via tours of key facilities, walkthroughs, demonstrations, and examination of documentation; and

- meeting with departmental staff involved in planning or delivering the program, which included a visit to the AAD’s head office in Tasmania.

1.21 The ANAO also received a submission via the citizen contribution facility on the ANAO website.

1.22 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $439,725.

1.23 The team members for this audit were Se Eun Lee, Jade Ryan, Lorcan Stevens, Jacqueline Hedditch and Nathan Callaway.

2. Governance and strategic planning

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Australian Antarctic Program (the program) is supported by appropriate governance and strategic planning arrangements.

Conclusion

The program is supported by partly appropriate governance and strategic planning arrangements. New governance and strategic planning arrangements were established in 2023 and 2024 to support the delivery of the program. Ongoing effort is required to embed these new arrangements into the Australian Antarctic Division’s (AAD’s) operations given the high-risk operating environment. Greater clarity is needed to guide the AAD’s risk management activities, including stronger oversight over the management of severe and fatal risks. Workforce planning is primarily focused on the short term rather than the long term. It is not integrated into broader planning arrangements. The department does not effectively monitor expeditioners’ compliance with mandatory training.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made five recommendations aimed at: implementing a risk strategy and supporting resources; improving the oversight and management of fatal risks; better alignment of its planned activities with the government’s key commitments; establishing enhanced workforce planning; and strengthening assurance over mandatory training compliance.

2.1 The AAD is a division within the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (the department). The department, through the AAD, is responsible for leading, coordinating and delivering the program, which encompasses Australia’s activities in Antarctica from scientific research through to logistics and infrastructure works.

Has the department established appropriate oversight arrangements to support the delivery of the program?

New oversight arrangements were established in 2023 and 2024 to support the delivery of the program. These governance structures require ongoing effort to grow their maturity as they are embedded into the AAD’s operations. Risk management activities are occurring, but they are not guided by a clear risk strategy tailored to the AAD’s operational context, which heightens the likelihood that critical risks may not be properly identified, assessed, and mitigated. The AAD’s severe and fatal risks are escalated and discussed in governance forums. However, there is a need for stronger oversight over these risks, including clearer articulation of risk controls and treatments, and informed acceptance of the risks by senior management, in order for the department to effectively demonstrate its compliance with WHS obligations.

2.2 In October 2022, the department engaged consultants Russell Performance Co. to conduct an independent review into the AAD’s workplace culture (the Russell Review). The Russell Review’s final report was published in April 2023, making findings regarding the AAD’s culture, capability and governance. In relation to leadership at the AAD, the Russell Review found:

a significantly separated culture, siloed on a range of levels, and a leadership culture contributing to a troubling lack of psychological safety. … A fresh leadership approach is needed to drive collaboration, communication, and connection between branches, Kingston and Antarctic work sites, the Division, and the broader Department to which it belongs.10

2.3 The Russell Review made 23 recommendations to the department under seven guiding principles. Principle 1 related to ‘Effective governance, oversight and monitoring to build a culture of respect and equality’, and made recommendations on:

developing strong and visible Division processes to accelerate cultural transformation, address staff concerns, and build trust among and between AAD people and the broader DCCEEW [the department]. This includes creating stronger lines of oversight and the opportunity to utilise external expertise to build diverse workplace culture in Australian and Antarctic workplaces.11

2.4 New governance arrangements were established in the AAD in 2023 and 2024 to enact cultural change, improve oversight over program delivery, support the division’s capacity to provide input to the broader department, and respond to the Russell Review’s recommendations. Figure 2.1 illustrates the AAD’s governance structure as at October 2025.

Figure 2.1: Australian Antarctic Division governance structure

Source: Adapted by ANAO from the department’s records.

2.5 The Executive Board is responsible for the overall governance, management, policy leadership and strategic direction of the department. It comprises the Secretary and deputy secretaries, and is assisted by five governance sub-committees. The AAD Head of Division is responsible for overseeing the AAD’s activities and reporting on divisional performance to the relevant deputy secretary and the department’s Secretary.

2.6 The Audit Committee provides ‘independent, objective assurance and consulting services designed to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of [the department]’s operations’.

2.7 The Australian Antarctic Science Council was established in 2019 to advise the government on the Australian Antarctic Science Program (see paragraph 1.10). It is led by an independent chair appointed by the Minister for the Environment and Water, and comprises two independent members and ex-officio positions reserved for representatives from government and non-government (research) organisations.

2.8 The Respect, Equality and Reform Council was established in July 2023 to advise on and drive the implementation of cultural reform at the AAD, and to monitor the implementation of the department’s response to the Russell Review.

2.9 The Major Projects Board (MPB) replaced the Program Management Board (PMB) in November 2024. The role and functions of the PMB, the MPB and the Division Management Committee (DMC) are examined below.

Program Management Board

2.10 The PMB met for the first time on 23 February 2023. According to its terms of reference, the PMB was to be ‘responsible for approval of, and visibility and oversight of, major initiatives undertaken by the Division’, and was to ‘oversee progress of major initiatives in all areas of AAD activity’. Its membership comprised:

- Deputy Secretary responsible for the AAD (Chair);

- AAD Head of Division;

- AAD branch heads;

- the department’s Chief Financial Officer;

- the department’s Chief Operating Officer; and

- an independent member (external).12

2.11 The PMB met monthly until July 2023, and then quarterly until August 2024, when it was disbanded and replaced with the MPB (see paragraphs 2.13 to 2.17). The PMB received reports on: the AAD’s budget; workplace health and safety (WHS); workforce planning; season planning and longer-term planning outlook; and governance reforms. The PMB also conducted ‘deep dives’ on key AAD initiatives, including the commissioning of the icebreaker vessel RSV Nuyina, projects being undertaken on Macquarie Island, and the Antarctic Infrastructure Renewal Program.13

2.12 At its eleventh meeting held on 29 August 2024, members’ endorsement was sought for the closure of the PMB and the establishment of the MPB. The meeting paper noted that ‘[g]overnance arrangements within the Division have matured over the past year’, and that the establishment of the DMC (in January 2024) had led to overlaps in agenda items, such as WHS and financial reporting. The members endorsed the closure of the PMB, with the majority of its functions transferred to the DMC, and the establishment of the MPB to oversee high-value, high-risk projects in the division. These changes were endorsed by the Secretary on 7 November 2024.

Major Projects Board

2.13 The MPB met for the first time on 6 November 2024. It meets four times per year and may hold additional meetings as needed. MPB membership comprises:

- Deputy Secretary responsible for the AAD (Chair);

- AAD Head of Division;

- the department’s Chief Financial Officer;

- Parks Australia Chief Operations Officer; and

- an independent member with expertise in governance and major project delivery.14

2.14 The terms of reference state that the MPB’s purpose is to:

[serve] as an advisory body to provide enhanced oversight and guidance for the delivery of the Australian Antarctic Division’s (AAD) major projects and initiatives. It focuses on projects with significant strategic importance, complexity, budgetary implications, or risk profiles.

2.15 The MPB is intended to ‘complement existing project governance structures without duplicating or interfering with day-to-day project management’. Under its terms of reference, the scope of its oversight extends to major projects and initiatives that meet the following criteria:

- An estimated investment of more than $10 million.

- Designation as a Major Project by senior leadership.

- Additional oversight requirements due to complexity and risk profile.

2.16 The MPB terms of reference do not define a ‘major project’, or what level of complexity or risk profile would necessitate additional oversight requirements. There is no project management framework at the department or the AAD that provides guidance on these matters. Paragraphs 3.35 to 3.40 examine project management arrangements in further detail, and paragraphs 3.47 to 3.51 outline the inconsistent oversight arrangements established for the key deliverables for the 2024–25 season.

2.17 As at June 2025, the MPB is overseeing 13 major projects and initiatives, including the Macquarie Island Station Project, the Denman Marine Voyage, and the Million Year Ice Core project. These three projects are examined further in Chapter 3.

Division Management Committee

2.18 The department’s response to the Russell Review stated that:

A Planning Committee will be established and will agree an integrated planning outlook for all major activities, including for Antarctic summer seasons, across a three-year planning horizon. The Planning Committee will meet quarterly to track progress.

2.19 At a meeting held on 26 July 2023, the PMB considered a proposal for an uplift of the AAD’s governance arrangements and structure, in order to ‘support the Head of Division … in their duties, and provide transparency, accountability and integrity in the Division’s decision making and planning’. The draft AAD governance structure included a proposed Division Management Committee, ‘which would replace the function of the former AAD Executive Committee and incorporate the proposed Planning Committee’.

2.20 The draft terms of reference and meeting schedule for the DMC were endorsed by the PMB at its eighth meeting held on 28 November 2023. On 18 December 2023, the Head of Division agreed to establish the DMC and hold the first meeting in January 2024.

2.21 The DMC agreed to its terms of reference at its first meeting held on 23 January 2024. The terms of reference state that the DMC:

is an SES-level forum for discussions on strategic priorities, opportunities for and barriers to the operation of the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) and the delivery of the Australian Antarctic Program.

2.22 Membership comprises the Head of Division as chair, the AAD Chief Scientist, AAD branch heads, and two Executive Level 2 members chosen on a rotational six-monthly basis. It is not a decision-making body and its role is to consider and provide advice to the Head of Division on strategic issues relevant to the delivery of AAD objectives.

2.23 The DMC meets monthly. Meeting records are complete, with agendas and papers prepared ahead of the meeting and meeting minutes and outcomes drafted following the meeting. The DMC receives updates on finance, WHS and division risks at each meeting, although its oversight and management of fatal risks require improvement (see paragraphs 2.50 to 2.59). Other key items of discussion at the DMC include: season planning; integrated planning; updates on key projects being delivered; and updates to divisional policies and procedures.

2.24 A number of issues arose during the establishment and transition of governance bodies, including in handover of action items (see paragraphs 3.31 to 3.32) and project oversight arrangements (see paragraph 3.50) between bodies. Further improvements to the AAD’s governance arrangements are being made via a governance improvement plan, which was presented to the DMC at its 20 May 2025 meeting for endorsement. Key actions to be delivered to December 2025 include strengthening project management capability for major projects, strategic planning and corporate planning arrangements.

Risk management

Division risk framework

2.25 Prior to 2022, the AAD had in place the 2020–2021 AAD Risk Management Framework, AAD Risk Management Policy and AAD Risk Management Guidelines. These documents outlined: the roles and responsibilities for managing risk in the AAD; risk governance structure; risk appetite and tolerance; types of risk registers established to manage risks; risk reporting and monitoring; and when and how to undertake risk assessments and utilise the AAD’s risk management tools.

2.26 In 2022, the department commenced consultation with its divisions, including the AAD, to review and develop its Enterprise Risk Management Framework (ERMF). The ERMF was approved and published in March 2023, and updated in September 2023. The ERMF outlines the department’s approach to effective risk management and defines the departmental risk appetite and tolerance. Since its publication, the AAD has used the ERMF as ‘the primary document referenced by the AAD when managing risk’, and the division-specific risk documents were withdrawn.

2.27 The ERMF states that ‘[t]o support implementation of the framework, a business area may choose to develop supporting risk management policies, tools or guidance material’. These must ‘comply and align with the framework’s guiding principles, requirements and expectations for managing risks, and support implementation of the department’s Risk Appetite and Tolerance Statements’.

2.28 The ERMF is supported by the Enterprise Risk Reference Guide (ERRG), which provides ‘detailed guidance and information to assist staff in identifying and managing risk in their day-to-day work’. The ERRG states that business areas should develop a risk strategy ‘[w]here you have specific context or operating environment and need to define the scope, roles and reporting for risk management that do not follow generic guidance’. It states that ‘[a] risk strategy should clearly outline your business area’s approach, expectations, prioritisation, and plan for managing risk in pursuit of your objectives’.

2.29 While the ERMF provides a high-level overview of departmental risk management processes, the AAD does not currently have a risk strategy that outlines its approach, expectations, priorities, or plan for managing risk. A range of risk management tools are in use across the AAD, including for undertaking hazardous work in Antarctica. However, there is no division-level guidance outlining how the relevant risk management tools should be used to ensure a consistent and coherent approach to managing risks in the division.

2.30 Considering the AAD’s high risk profile, the lack of an appropriate risk management strategy and guidance impairs the ability of the department to assure itself that critical risks are properly identified, assessed and managed. This could increase the potential risks of safety incidents, operational disruptions, and failure to achieve program objectives.

2.31 On 16 May 2025, the MPB held a ‘deep dive’ into the AAD’s approach to risk management, which included a discussion of a draft infographic developed to help staff to better understand the division’s risk management processes. The infographic was finalised following the meeting and made available to staff via the AAD intranet on 19 June 2025. The AAD would benefit from developing a risk strategy to accompany the infographic and provide staff with guidance and support in undertaking risk management activities.

Recommendation no.1

2.32 The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water implement a risk strategy and supporting resources for the AAD, outlining how its Enterprise Risk Management Framework should be operationalised and risks identified, escalated, and managed within the division’s operational context.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

2.33 The department proactively engages in risk management activities and risk practices for numerous projects and business as usual activities undertaken by the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD). This includes Job Hazards Analysis, incident investigations, crisis appreciation and scenario planning exercises, as well as regular review and oversight of divisional risks, Antarctic season operational risks, major project risks, WHS risks and fatal risks.

2.34 The department’s Enterprise Risk Management Framework (ERMF) was developed in 2022. The AAD contributed to its development to ensure the unique operating needs of the AAD were considered in the whole of department fit-for-purpose approach to risk management. Since then, the AAD’s risk management practices have been conducted consistent with the DCCEEW ERMF and guidance. We agree there is value in building on previous work to introduce a division-specific strategy that articulates how the ERMF is operationalised and risk management is undertaken in the AAD.

Division risk oversight

2.35 The ERMF states that ‘Business areas must record their risks using a risk register [emphasis in original]’, which should inform risk reporting.

2.36 The AAD has established a division risk register, which is updated regularly. Updates ranged from minor wording amendments for clarification, to substantial changes to risk scope and introduction of new risks.

2.37 The DMC is responsible for considering and providing advice on division risks under its terms of reference, with branch heads leading the discussion on a specific division risk at each meeting. As at its July 2025 meeting, the DMC discussed division risks relating to: the achievement of the AAD’s strategic objectives; WHS; reputation; internal governance, processes and systems; Antarctic infrastructure; impacts of climate change on AAD operations; the AAD workforce; and security of the AAD’s information.

2.38 Review of DMC meeting records indicates that members consider the current risk sources, the effectiveness of current controls, and additional potential treatments to further mitigate the risks. The division risk register is updated to reflect the discussion.

2.39 For example, in relation to the risk relating to the AAD’s internal governance, the relevant division risk was ‘Failure of AAD governance framework and systems (to enable effective, transparent decision making and accountability)’. The DMC conducted a deep dive into this risk at its December 2024 meeting, at which the members acknowledged the progress made in establishing and understanding governance frameworks across the division over the past 12 to 18 months, and requested that the risk be refined to more accurately reflect the nature of the risk and provide a broader strategic perspective.

2.40 An update on the governance risk was provided at the DMC’s May 2025 meeting, updating and refining the risk sources, consequences, controls and treatments. The DMC endorsed the revised risk assessment for the governance risk, subject to minor amendments to treatments and controls to ensure what was being proposed was achievable, not considered business as usual, and would have a demonstrable impact in reducing the overall risk rating.

2.41 The AAD facilitates regular risk assessment meetings to review individual division risks in preparation for the DMC’s monthly risk discussions. The DMC also holds biannual risk workshops to review division risks holistically. In 2024, DMC risk workshops were held in May and December, where the division risks were considered against the department’s enterprise risks, and changes to the division risk register were discussed and agreed. The first risk workshop of 2025 took place on 10 June, which included an overview of the AAD’s risk management approaches.

Division risk escalation

2.42 The ERMF provides a risk communication and governance model, which states that risks rated ‘severe’ should be ‘elevated to the Deputy Secretary immediately’, with ‘[r]isk communication, management and mitigation to take precedence over all other activities’.

2.43 Across 2024 and 2025 (to March 2025), there were three division risks that had been rated as ‘severe’15 at various points in time, either in their current or target risk rating:

- ‘WHS physical incident’;

- ‘WHS psychosocial incident’; and

- ‘Antarctic infrastructure is insufficient to support AAP objectives’.

2.44 These risks were escalated as required and discussed at the department’s Risk Committee (sub-committee of the department’s Executive Board) on 16 May 2024 and 25 February 2025. While the updates to the Risk Committee included an outline of efforts to mitigate the risks over the past 12 months, the records of the meetings did not clearly indicate whether: the mitigation efforts had been successful in reducing the risk ratings; the committee recommended any additional risk communication, management and mitigation activities to downgrade the risk ratings; or whether the Deputy Secretary, as the Senior Responsible Officer, had accepted the risks that were not able to be downgraded further.

Workplace health and safety risk management

2.45 One of the department’s eight enterprise risks is:

4. We do not protect and enable our own and each other’s health, safety and wellbeing and other people under our care.

2.46 Management of WHS risks is a key part of risk management at the AAD due to the nature of its operations.16 The AAD’s monthly WHS reporting indicates that incidents of ‘major’ or ‘catastrophic’ potential severity occur at an approximate average of four incidents per month.17 WHS risks also influence the AAD’s project and budget prioritisation, decisions on infrastructure investment, and recruitment and training processes.

2.47 Following a recommendation from a WHS management review in October 2023, a new ‘functional split’ of WHS responsibilities was agreed between the department’s central People Division and the AAD, which was endorsed by the DMC at its 20 May 2025 meeting.

- The People Division is responsible for: developing and maintaining the enterprise WHS management system; participating in reviews of the AAD’s WHS fatal risk register and monitoring the efficacy of their controls; and developing and monitoring safety improvement plans.

- The AAD is responsible for: developing and maintaining the divisional WHS management system; facilitating and monitoring the WHS fatal risk review process; and supporting the development of safety improvement plans in consultation with stakeholders.

Australian Antarctic Division workplace health and safety management system

2.48 The AAD intranet page on the WHS management system (as of 14 April 2025) refers users to the AAD Safety Management System Manual (SMS manual) for a ‘general description of AAD’s safety management system’, while noting that ‘[t]his document is currently subject to review and is incomplete’. The SMS manual indicates that:

- the AAD’s critical risks (including the risks in the Fatal Risk Register) are reviewed at least biannually and reported to the AAD executive with recommendations on priorities for improvement actions;

- operational and project-level risks should be managed in accordance with AAD Risk Management Policy and AAD Risk Management Guidelines (these documents were withdrawn in March 2023 — see paragraphs 2.25 to 2.26); and

- personal risks should be managed using risk management tools that are described in ‘AAD Safety Standard Personal Risk Management’ (this safety standard was not included in the list of safety standards in the appendix — see paragraph 2.52).

2.49 On 20 August 2025, the department engaged Endor Group Pty Ltd to provide technical expertise to assist with the revision of the AAD’s WHS documents. A project plan for the AAD WHS document uplift project has been developed, along with a schedule of documents for review. The project is planned to be completed by August 2027, subject to funding availability and extension of the contract.

Fatal risk management

2.50 Fatal risks are risks assessed as having the greatest potential to result in a workplace fatality. These risks are outlined in the AAD’s Fatal Risk Register, which is reviewed biannually by the AAD Fatal Risk Review Group. The outcomes of each review and the revised register are presented to the DMC, seeking endorsement of any changes to the fatal risk profile or the relative priority of planned mitigation works. In its February 2025 update, which was reviewed and endorsed by the DMC in April 2025, there were 38 fatal risk sources listed in the register, of which 14 were marked as ‘high’ priority for the AAD’s attention ‘for the purpose of planning risk mitigation works’ (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: Fatal risk sources with ‘high’ priority for the Australian Antarctic Division’s attention, February 2025

|

|

AAD fatal risk sources |

Worst credible single event outcome posed by risk source for AAD |

Self-assessed adequacy of current controls at AAD |

|

FR1 |

Foundering or major incident on a ship |

100+ fatalities |

Partially effective |

|

FR2 |

Aviation (intra & intercontinental, and helicopter) |

45+ fatalities |

Partially effective |

|

FR3 |

Station fire |

25+ fatalities |

Partially effective |

|

FR4 |

Earthquake / Tsunami — Macquarie Island |

20+ fatalities |

Partially effective |

|

FR5 |

Small watercraft — LARC and IRB/RIBa |

15+ fatalities |

Substantially effective |

|

FR8 |

Hazardous substances and dangerous goods |

2+ fatalities |

Largely ineffective |

|

FR9 |

Harm related to dynamic terrain (crevasses, tide cracks, unstable surfaces, etc.) |

2+ fatalities |

Substantially effective |

|

FR13 |

Failures of fixed plant & buildings (critical infrastructure) |

2+ fatalities |

Substantially effective |

|

FR14 |

Infectious and zoonotic disease |

2+ fatalities |

Partially effective |

|

FR16 |

Habitable building collapse secondary to a landslip — Macquarie Island |

2+ fatalities |

Partially effective |

|

FR17 |

Habitable building collapse secondary to a storm (high wind) event — Macquarie Island |

2+ fatalities |

Partially effective |

|

FR22 |

Psychosocial harms (including suicide, workplace violence, substance misuse or abuse, excessive workloads, etc.) |

Single fatality risk |

Substantially effective |

|

FR28 |

Asbestos exposure and other ‘industrial’ illness |

Single fatality risk |

Partially effective |

|

FR33 |

Accidental or mismanaged detonation of explosives |

Single fatality risk |

Partially effective |

Note a: LARCs (Lighter, Amphibious, Resupply, Cargo) and inflatable rubber boats (IRBs)/rigid inflatable boats (RIBs) are used for cargo and personnel transfers. They are also available for search and rescue.

Source: ANAO summary of AAD Fatal Risk Register, February 2025.

2.51 The Fatal Risk Register does not list the ‘current controls’ that are self-assessed for adequacy. Updates to the DMC do not list the controls that were considered in the self-assessment, or the criteria against which their efficacy was assessed. On 6 August 2025, the department advised the ANAO that ‘risk controls are embedded in AAD Standard Operating Procedures [SOPs] and safety standards’.

2.52 The SMS manual provides a list of ‘DCCEEW/AAD Safety Standards’ in appendix 1. The department advised the ANAO on 6 August 2025 that this is ‘a comprehensive list of documents that are currently in service and scheduled for development’. A total of 48 safety standards were listed. Half of the listed safety standards were marked as ‘under development’.

2.53 On 28 July 2025, the department provided the ANAO with an update on its progress in developing the safety standards. Of the 24 that were under development:

- three had been developed and were advised to be ‘current’;

- nine were still to be developed;

- five were in draft or otherwise pending release;

- five were addressed by another standard or content (three by departmental standards; one via Safe Work Australia; and one referred to content on the AAD intranet); and

- no status updates were provided for two.

2.54 The AAD’s intranet contains a page on WHS SOPs. There were a total of 42 SOPs linked across 12 sub-pages. The ANAO’s examination of document review dates indicates that all but one SOP were out of date as at August 2025, and the validity of a further two were unknown (no date of review specified).

2.55 In July 2024, Atturra (formerly Noetic Solutions Pty Ltd) was engaged to: conduct a review of the AAD’s WHS management system; and develop documents (such as standards, guidelines and procedures) to improve or fill gaps within the existing WHS management system.18

2.56 The desktop review was delivered on 27 November 2024, outlining key findings and recommendations relating to the AAD’s WHS management system. On 28 July 2025, the department advised the ANAO that ‘[t]he contract with Atturra ended in February 2025 following delivery of Phase 1’, and that ‘Atturra was not engaged to deliver Phase 2 of the works’.19 As outlined in paragraph 2.49, the department has approached the market to seek expertise to assist with the revision of the AAD’s WHS documents.

Safety improvement plan

2.57 The People Division, in collaboration with the AAD, develops an annual safety improvement plan (SIP) to address areas of deficiency ‘deemed to pose the greatest risk to safety’ and identified as priorities for improvement. The 2023–2025 SIP was approved by the Head of Division on 17 December 2023. The SIP outlined 35 ‘key initiatives’ to be delivered. Of the 14 ‘high’ priority fatal risk sources outlined in Table 2.1, 11 had an associated SIP initiative to improve their management.

2.58 It is not evident how the risks that are marked for ‘high’ priority for attention without a corresponding SIP initiative are being managed, including FR1 which has the highest potential fatality in a single event (100+), and FR2, which has the second highest (45+). While the DMC reviews and endorses the fatal risk register at relevant meetings, there is no clear indication of whether it has considered the need for additional treatments to mitigate any of the fatal risks, especially those without a corresponding SIP initiative or with controls that were self-assessed as ‘partially effective’.

2.59 An effective risk management process requires a clear and shared understanding of the risk controls in place and any additional treatments required, and informed acceptance of the final risk rating by senior management. This is critical for assurance that all reasonable steps are being taken to manage hazards that can credibly lead to one or more fatalities. The process should be underpinned by robust record-keeping practices to demonstrate the department’s compliance with WHS obligations.20

Recommendation no.2

2.60 The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, in managing the AAD’s fatal risks, establish arrangements to ensure:

- its safety standards and standard operating procedures are developed, reviewed and updated in a timely manner, to prevent risks of staff operating under unwritten or potentially outdated instructions;

- it is clear what controls are in place for each fatal risk and how their efficacy was considered in self-assessments;

- its governance bodies, in their reviews of the fatal risk register, clearly indicate whether any fatal risks require additional treatments, or have been discussed and accepted as being adequately controlled without the need for further treatments; and

- these processes and decisions are clearly documented in accordance with the department’s record-keeping and WHS obligations to demonstrate compliance and support accountability.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

2.61 Ensuring the safety and wellbeing of our staff, both expeditioners and head office staff, is of the utmost importance to the department. The AAD engages in WHS risk management across our operations. Controls are in place and enacted frequently to minimise risks to safety. These controls are documented in the numerous Standard Operating Procedures and Job Hazard Assessments provided for AAD activities. In recognition of the unique and challenging environment in which the Australian Antarctic Program is delivered, in March 2025 the department established a dedicated WHS team in the AAD to focus on the identification, assessment and mitigation of fatal risks. The department welcomes the ANAO’s recommended improvements.

Is the department undertaking appropriate strategic planning to determine program priorities?

New strategic planning arrangements were introduced in 2023 and 2024 to help deliver the priorities outlined in the strategy and action plan. These arrangements, once embedded, have the potential to improve the AAD’s strategic planning to determine, document and operationalise program priorities. Development and finalisation of the implementation plan for the Australian Antarctic Science Decadal Strategy and the infrastructure masterplans may help the AAD to more clearly articulate the science and non-science priorities for the Australian Antarctic Program and align them to its planned activities.

2.62 In December 2024, the Head of Division approved the AAD’s ‘strategic architecture’, which ‘provides a visual overview of the hierarchy and inter-relationship between the AAD’s core strategic and planning documents as they relate at a strategic, operational, and tactical level’. It was updated in March 2025 and is represented at Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: Australian Antarctic Division strategic architecture

Source: Adapted by the ANAO from the department’s records.

Administrative Arrangements Order

2.63 The Administrative Arrangements Order (AAO) allocates executive responsibility among ministers. It sets out which matters and legislation are administered by which department or portfolio.

2.64 The AAO (13 May 2025) states that the department is responsible for ‘Administration of the Australian Antarctic Territory, and the Territory of Heard Island and McDonald Islands’.

Portfolio Budget Statements, corporate plan and annual report

2.65 There are three key accountability documents produced by entities under the Commonwealth performance framework established under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act):

- Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS) — the primary financial planning document;

- corporate plan — the primary non-financial planning document; and

- annual report — incorporates financial statements and annual performance statements that outline the financial and non-financial results achieved by entities.

2.66 The department’s functions relating to Antarctica and the sub-Antarctic region fall under its PBS Outcome 3, which specifies one key activity. The corporate plan specifies three performance measures under the key activity. Reporting against the performance measures is examined at paragraphs 4.18 to 4.22.

Division plan

2.67 According to departmental guidance, a division-level business plan is an important part of corporate planning (Figure 2.2). It helps identify challenges and risks specific to the relevant business area, and supports understanding of how the division’s work contributes to delivering the department’s broader outcomes.

2.68 In July 2023, the Executive Board agreed to an interim division planning and risk management approach to align with the release of the 2023–24 Corporate Plan, focusing on key priorities and risk registers. The AAD developed a division plan for 2023–24, which outlined four strategic priorities for the division, as well as cross-collaboration activities the division is contributing towards various departmental functions.

2.69 The AAD did not establish a division plan for 2024–25. On 8 May 2025, the department advised the ANAO that it:

did not require divisions to update division business plans in 2024–25. Instead, templates for the optional updating of Divisional Business Plans were provided to Heads of Divisions in December 2024. …

The Department will release additional information on division level business planning to support implementation of the department’s 2025–26 Corporate Plan. … AAD will update its Division Business Plan to meet the requirements of the broader department at that time.

2.70 The ANAO examined the department’s corporate planning process in Auditor-General Report No. 30 2023–24 Corporate Planning in the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. The audit found that ‘Priorities identified in the corporate plan are not yet reflected through a mature divisional planning process’.21 The absence of robust division planning arrangements for 2024–25 indicates that the department’s divisional planning process requires further maturity.

Australian Antarctic Strategy and 20 Year Action Plan

2.71 The 2016 Australian Antarctic Strategy and 20 Year Action Plan (strategy and action plan) outlines seven national interests (see paragraph 1.8) and the actions the Australian Government will undertake from 2016 to 2036. The strategy and action plan was updated in 2022 following a five-year review of progress. Implementation tracking and reporting against the strategy and action plan are examined at paragraphs 4.4 to 4.8.

Australian Antarctic Science Decadal Strategy

2.72 The 2022 update to the strategy and action plan committed to ‘develop[ing] a ten-year Antarctic Science Plan … to implement Australia’s Antarctic strategic science priorities’.

2.73 The Australian Antarctic Science Decadal Strategy (decadal strategy) was developed by the Australian Antarctic Science Council (see paragraph 2.7) and released on 28 February 2025. The decadal strategy ‘reflects the highest priority scientific outcomes that advance Australia’s national interests in Antarctica, the Southern Ocean and sub-Antarctic islands’ as articulated in the strategy and action plan. It identifies three priority research themes for the next 10 years, comprising:

- climate system and change;

- biodiversity; and

- human impacts.

2.74 The department has not set a timeframe for the development of an implementation plan for the decadal strategy. On 10 October 2025, the department advised the ANAO that ‘[t]he timing and design of the implementation plan is being driven by the department in consultation with the Australian Antarctic Science Council’.

Infrastructure masterplans

2.75 The 2022 strategy and action plan included a commitment to ‘[d]eliver a comprehensive Masterplan for Antarctic stations to tackle ageing infrastructure’ within five years. On 28 July 2025, the department advised the ANAO that the ‘development of the masterplans is still in progress’, with a number of key documents, including an interim design report, produced to date.

Three-year summary

2.76 As outlined at paragraph 2.18, the department’s response to the Russell Review committed to developing an ‘integrated planning outlook … across a three-year planning horizon’ for the AAD. Previously, the AAD operated under a five-year forward plan outlining the ‘major actions and measures of success’ across four delivery pillars and key enabling measures.

2.77 In April 2023, a ‘cross-branch Integrated Planning Tiger-Team’ was established to advise and assist in developing a three-year plan. E3 Advisory Pty Ltd was engaged by the department to ‘deliver services in support of a sprint22 to develop a three-year plan for AAD’.23 E3 Advisory’s work on the three-year planning process commenced on 26 April 2023, before the Order for Service was formally executed on 24 May 2023. The department advised the ANAO on 28 May 2025 that this had occurred due to the need to establish an ‘ethical wall’24 to manage potential conflicts arising from E3 Advisory’s existing engagement with the department in relation to an infrastructure project in Antarctica, which had delayed the execution of the Order for Service. The department retroactively reported this as a breach in its procurement system on 17 July 2025, but the department advised the ANAO on 10 October 2025 that this action was later found to not be a breach of the department’s Accountable Authority Instructions or procurement policy, and withdrew the report.25

2.78 The purpose of the sprint was to develop a three-year plan for the AAD that: was aligned to the division’s budget allocation, resources and logistics capability; and delivered on government commitments. The aim was to deliver the three-year plan ‘in final draft form to the Minister for the Environment and Water by the first week of June 2023, to commence on 1 July 2023’.

2.79 Updates on the sprint were provided to the PMB at its meetings in May and June 2023. The PMB was informed that the division’s activities identified through the sprint ‘are very likely to exceed budget and [Full-Time Equivalent (FTE)] in 2023–24 and beyond’, and that ‘[s]ome activities will need to be ceased and others reprioritised for later years’.

2.80 A final draft of the three-year plan was due by the first week of June 2023. The PMB meeting minutes of 26 June 2023 did not mention the missed deadline or a revised timeframe for its completion.

2.81 The three-year plan underwent multiple drafts throughout the remainder of 2023 and across 2024. The final draft document was provided to the minister for noting on 10 December 2024, with the minister signing the accompanying brief on 23 December 2024. In the brief, the department advised the minister that:

The Antarctic program remains oversubscribed — in part due to challenges presented by the COVID19 pandemic and poor governance and planning within the Australian Antarctic Division over many years (highlighted in the Russell Review). Promises have been made in isolation without due consideration of deliverability of interdependencies.

In spite of the investment made by the government (over $1.3 billion in the Antarctic program since 2022), we are unlikely to achieve all of the specific actions committed to in the 2022 Update to the Strategy and Action plan.

2.82 On 24 December 2024, the Head of Division sent out an all-staff email formally announcing the endorsement of the document, which was titled ‘Three Year Summary to June 2026’ (three-year summary).26 The three-year summary outlines a list of commitments to be delivered to June 2026 under six focus areas (see paragraph 2.89). It is to be updated annually, with its first update scheduled in December 2025. The annual update to the three-year summary, identifying and confirming the division’s strategic priorities, leads into the integrated planning process for upcoming seasons.

Integrated planning process

2.83 On 25 May 2023, the department engaged UBH Group for ‘Operational Augmentation Support to the Australian Antarctic Division’.27 UBH’s initial scope of work related to ‘operations planning process’, which became the ‘Season Operations Planning Process (SOPP)’. The SOPP is examined at paragraphs 3.2 to 3.25.

2.84 The UBH contract underwent five change orders. Change Order 2 (April 2024) added a new stream of work on ‘Strategic Planning Reform’. Change Order 728 (September 2024) extended UBH’s support services ‘until completion in early 2025’ and amended the stream ‘Strategic Planning Reform’ to ‘Integrated Planning Process (IPP) Design & Implementation’.

2.85 The UBH contract and its amendments were not accurately reported on AusTender in accordance with the requirements in the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.29 On 23 June 2025, the department advised the ANAO that the reporting error ‘may have been a consequence of an error during bulk data migration from a former department’s financial management system’.

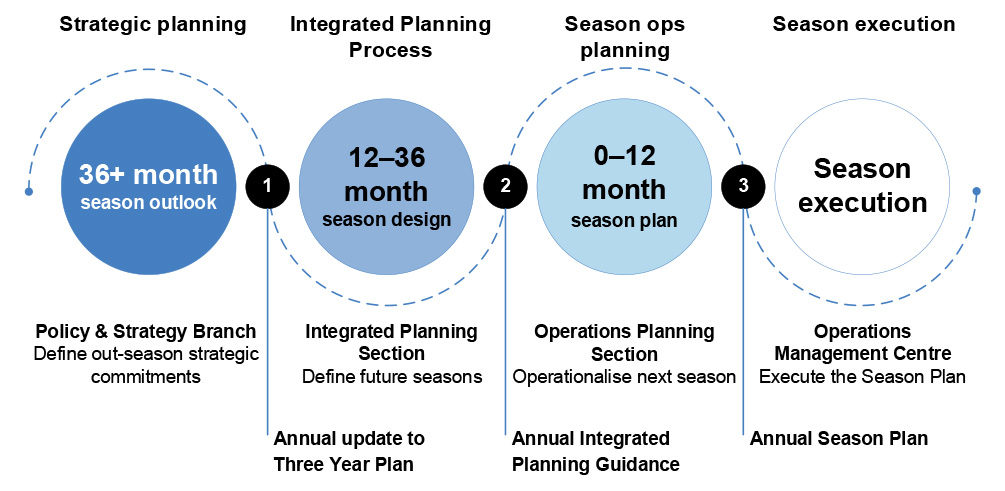

2.86 The IPP project commenced in March 2024. Following stakeholder engagement in April 2024, UBH Group produced a design model of the IPP in July 2024, which was provided to the DMC for discussion at its 24 August 2024 meeting (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3: Integrated planning model

Source: Adapted by ANAO from the department’s records.

2.87 In September 2024, as the three-year plan (which would initiate the IPP) was still being developed, a document outlining AAD strategic commitments for the 2025–26 season was issued by the Head of Division to inform the first IPP. On 25 March 2025, pending the first annual update to the three-year summary, a document outlining strategic commitments for the 2026–27 season and indicative strategic commitments for the 2027–28 season were approved by the Head of Division to initiate the next IPP.

2.88 The department advised the ANAO on 28 May 2025 that the intention is for the three-year summary — which is currently to June 2026 — to be updated in December 2025 to realign with and inform the next IPP.

Alignment of key strategic documents

2.89 The three-year summary outlines six focus areas to prioritise the delivery of Australia’s commitments in the strategy and action plan. These focus areas align with the high-level priorities outlined in the 2022 update to the strategy and action plan (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2: Alignment between strategy and action plan and three-year summary

|

Strategy and action plan priorities 2022–2026 |

Focus areas in Three Year Summary to June 2026a |

|

Leadership in Antarctica |

Maintaining and enhancing Australia’s leadership and influence within the Antarctic Treaty system, and positioning Australia as a partner of choice in East Antarctica |

|

Leadership and excellence in Antarctic science |

Conducting robust, excellent science for and in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean |

|

Leadership in environmental stewardship |

Protecting and conserving the environment and repairing and managing Antarctica for future generations |

|

Develop economic, educational and collaborative opportunities |

Securing our operations in Antarctica and the Southern Oceanb |