Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Department of Defence’s Sustainment of Canberra Class Amphibious Assault Ships (Landing Helicopter Dock)

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The Royal Australian Navy’s (Navy) amphibious warfare fleet includes two Canberra class amphibious assault ships, known as landing helicopter docks (LHDs).

- Since entry of the LHDs into service in 2014, Defence has contracted its core LHD sustainment delivery activities to industry.

- This audit provides assurance to Parliament on the effectiveness of Defence’s sustainment arrangements for the LHD capability.

Key facts

- Arrangements for the sustainment of the LHDs have changed over time across three contractual phases or models: transition to sustainment; asset class prime contractor; and the Maritime Sustainment Model.

- LHD sustainment has the fourth highest expenditure across all sustainment products in the maritime domain, with funding of $180 million in 2024–25.

What did we find?

- Defence’s arrangements for the sustainment of Navy’s LHDs have been partly effective.

- Defence did not plan effectively for the transition from acquisition to sustainment. Value for money was not clearly demonstrated and probity was not well managed in the three relevant procurement activities.

- Defence has not managed its LHD sustainment contracts effectively. The LHDs have operated with ongoing deficiencies and have experienced critical failures during operations.

- Monitoring and reporting in respect to LHD sustainment outcomes, the extent to which Navy’s requirements have been met, and the implementation of the Maritime Sustainment Model arrangements has been partly effective.

What did we recommend?

- There were nine recommendations to the Department of Defence aimed at improving: the transition from acquisition to sustainment; effective management of sustainment; and contract management, including potential fraud concerns.

- Defence agreed to the recommendations.

$.9 bn

estimated cost of LHD sustainment for the decade to 2033–34

30 years

remaining on the LHDs’ planned life-of-type, with withdrawal planned for 2055 and 2056

223

open urgent defects reported for the LHDs in June 2025

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Royal Australian Navy (Navy) amphibious warfare fleet includes two Canberra class amphibious assault ships, also known as landing helicopter docks (LHDs). These are HMAS Canberra, commissioned in November 2014, and HMAS Adelaide, commissioned in December 2015. The role of the LHDs is to provide capabilities in amphibious warfare, humanitarian assistance, disaster relief and sealift, and to contribute to broader naval activities. Effective sustainment of the LHDs, including maintenance and support, is essential for the effective delivery of these capabilities.

2. Defence’s Naval Shipbuilding and Sustainment Group has been responsible for the sustainment of the LHDs on behalf of the Navy (the capability manager) since October 2022.1 Since entry into service in 2014, Defence has contracted its core LHD sustainment delivery activities to industry. Defence’s contracting model has changed from time to time, with each of the arrangements established at the commencement of the following three phases: the transition from acquisition to sustainment (from 2014 to 2019); the asset class prime contractor model (from 2019 to 2024); and the Maritime Sustainment Model (as of 1 July 2024).

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. In 2024–25, Defence’s sustainment activities for its fleet of two Canberra class amphibious assault ships, or LHDs, had a funding provision of $180 million (estimated at $1.9 billion to 2033–34). With service life-of-type until the mid-2050s, the LHDs provide Navy with amphibious capabilities which are to support the delivery of the Australian Government’s strategic intent through joint Australian Defence Force (ADF) deployments. This audit provides assurance to the Parliament on Defence’s sustainment of naval capability, building on Auditor-General Report No. 30 2018–19 ANZAC Class Frigates — Sustainment.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The audit objective was to examine the effectiveness of Defence’s sustainment arrangements for Navy’s Canberra class fleet of amphibious assault ships (or LHDs).

5. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Has Defence implemented fit-for-purpose planning and value for money procurement arrangements to support its sustainment activities?

- Has Defence effectively managed its sustainment contracts?

- Has Defence established appropriate performance monitoring and reporting arrangements?

Conclusion

6. Defence’s sustainment arrangements for Navy’s LHDs have been partly effective. Risks arising from an accumulation of defects and maintenance backlogs over several years have materialised. The substandard condition of the vessels, and personnel workforce shortages, have resulted in instances of critical failure and impacts to the Navy’s delivery of operational outcomes.

7. Defence did not implement fit-for-purpose planning and value for money procurement arrangements to support LHD sustainment. Defence’s future sustainment requirements, including access to important intellectual property for the LHDs, were not sufficiently developed during the acquisition phase. Establishment of the sustainment arrangements was delayed, occurring during the transition to sustainment process and alongside remediation activities to address issues persisting from acquisition. Defence’s remediation activities did not achieve the required outcomes, resulting in additional work being transferred to the sustainment phase or managed as part of capability improvement projects.

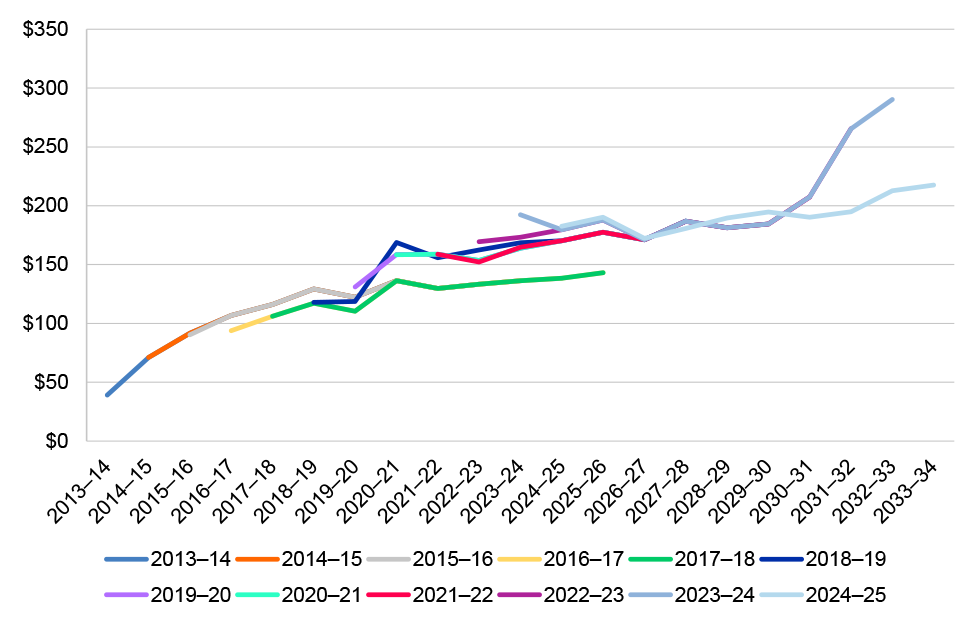

8. Value for money and the intended sustainment outcomes were not achieved through Defence’s procurement processes. Early cost estimates for the sustainment of the LHDs were under developed and did not anticipate the impact of the protracted acquisition deficiencies extending into sustainment and continuing into 2025. Defence has regularly reviewed and adjusted its sustainment budget.

9. Sustainment of the LHDs was not managed effectively by Defence through its prime contractor arrangements. Governance arrangements, contract management guidance, and risk management practices were not implemented in a timely manner and contract-specific probity arrangements were not developed. Defence did not take reasonable steps, as required by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), to manage systemic poor procurement practices by the prime contractor or investigate claims of fraudulent activity in sub-contracting arrangements in accordance with its own policies. Defence did not use the full range of contractual levers available to manage its primary sustainment contract. This approach impacted the quality of service delivery and undermined the achievement of value for money through the contract.

10. Defence has established partly appropriate performance monitoring and reporting arrangements for the Canberra class LHDs. Sustainment outcomes have largely met Navy’s requirements for the operational use of the platforms. The long-term availability and reliability of the LHDs is at risk primarily due to the accumulation of urgent defects, maintenance backlogs and shortfalls in personnel to undertake organic level maintenance. As a result, the LHDs have experienced critical failures, impacting on Navy operations.

11. Defence’s transition to the new Maritime Sustainment Model lacked reliable and complete information on the expected performance of sustainment contractors. Value for money outcomes for the procurements under the new model were limited by poorly implemented probity arrangements and the procurements commencing later than planned, reducing the time available to resolve issues during contract negotiations.

Supporting findings

Planning and procurement

12. Defence accepted delivery of the ships from BAE in 2014 and 2015 later than planned and with defects and deficiencies in both vessels, many of which remain unresolved.

- In 2017, Defence established a Transition and Remediation Program (TARP) to manage the transition into sustainment and conduct the remediation work required to achieve the full capability expected from the LHDs. The remediation activities did not achieve all the intended outcomes, and in November 2019, Defence accepted the LHDs into full service with six ‘significant residual deficiencies’.

- In 2021, Defence established a capability assurance program to address urgent operational and safety issues for the LHDs, including issues carried over from the TARP.

- In July 2024, one quarter of the way through the planned life of the ships, Defence closed the acquisition project with significant defects and deficiencies from acquisition remaining unresolved and to be managed during the sustainment phase (see paragraphs 2.2 to 2.21).

13. The integrity of Defence’s procurement processes for the LHD sustainment prime contractors was undermined by poor controls over probity risks.

- In 2014, the Capability Support Coordinator contract was awarded following an open tender process. The effectiveness of this procurement was limited by issues in the planning and evaluation processes. There were also shortcomings in the subsequent extension of the services with the incumbent provider under the Major Service Provider Panel following an unsolicited proposal in 2022.

- In 2014, the Transition In-Service Support Contract was awarded following a ‘collaborative’ sole source procurement process involving protracted engagement by Defence to improve an under-developed tender response. The procurement outcome did not demonstrate value for money.

- In 2018, the Asset Class Prime Contractor was awarded following a two-stage selection process which involved assessments against fit-for-purpose evaluation criteria. The integrity of the process was compromised by the departure of a senior Defence official with early involvement in the procurement who was then employed by, and negotiated with Defence on behalf of, the winning tenderer (see paragraphs 2.22 to 2.77).

14. Defence’s forecast and management of sustainment costs have been impacted by deficiencies from acquisition extending into sustainment. Since final operating capability was declared in 2019, the LHD sustainment funding provision per financial year has not met in-year requirements, with some sustainment work deferred and future costs increasing. In 2024 senior Defence officials considered options to address Navy sustainment funding pressures. Following consultation with the Minister for Defence in 2024, Navy sustainment funding was increased by an additional $300 million over two years to June 2026, of which Defence allocated $36 million towards LHD sustainment funding for 2024–25 (see paragraphs 2.78 to 2.88).

Sustainment management

15. Defence established governance arrangements to support its management of LHD sustainment contracts. These arrangements were either not implemented effectively or not maintained by Defence, resulting in a number of shortcomings.

- Since 2012, updates to the Materiel Sustainment Agreement (head agreement) between Navy and the Naval Shipbuilding and Sustainment Group have not been timely, occurring several years after key changes in responsibilities or organisational restructures had taken effect.

- A contract management plan was not established for the first 17 months of the ACPC contract. Contract risks, including those identified during the procurement process, were not revisited as planned or covered in the contract management plan.

- Contract-specific probity arrangements were not established for the ACPC contract. Defence relied solely on its broader departmental arrangements instead, which require Defence personnel to proactively identify and declare any actual, potential or perceived conflicts of interest as and when they arise.

- LHD sustainment risks at the strategic level are managed separately and in isolation from risks at the operational and technical levels. There is no hierarchy or clear line of sight between the risks identified in the Materiel Sustainment Agreement and those being managed day-to-day (see paragraphs 3.2 to 3.32).

16. Defence did not manage its primary LHD sustainment contracts as intended by its performance-based design. As a result, Defence cannot assure itself or ministers that sustainment services were delivered effectively and in accordance with the contracted requirements. Key deficiencies were that Defence did not:

- ensure that all mandatory reports were submitted in a timely manner by the contractor;

- undertake full or timely assessments of the contractor’s performance;

- ensure that all key sustainment deliverables had been completed in full prior to making payments to the contractor; or

- use the full range of levers available in the contract to drive satisfactory performance.

17. Between 2021 and 2023 there were at least three separate allegations of fraudulent activities or instances of poor sub-contracting practices related to the ACPC contract. Defence did not seek further information from the contractor on the 2023 allegations and did not change its approach to managing the contract after being notified of the various issues (see paragraphs 3.33 to 3.79).

Performance monitoring and reporting

18. Defence has established a sustainment performance framework for the LHDs, with performance measures set out in a written agreement and reporting provided to senior Defence leadership. The performance measures adopted are relevant to the LHDs but are not fully reliable and do not provide a complete and clear picture of sustainment performance as some important areas of sustainment are not covered. For some performance measures, the nature of the targets selected has led to reporting that does not provide a fair presentation of performance results for the LHDs (see paragraphs 4.2 to 4.18).

19. Navy’s operational requirements have been impacted by shortcomings in the management of LHD sustainment. Sustainment outcomes have included an accumulation of urgent defects, persistent maintenance backlogs, and the degradation of the condition of the platforms. The LHDs have fallen short of meeting availability targets since 2020–21 and sustainment-related deficiencies and workforce shortfalls have given rise to risks involving critical failures in the vessels, possible damage to Navy’s reputation and concerns for the sustainability of the LHDs over the long-term. Some of these risks have materialised, including:

- total power failures in 2022 and 2023, making the LHDs temporarily unavailable while providing humanitarian assistance and disaster relief support in Tonga and Vanuatu; and

- a reduction from three ships to two available for deployment in the amphibious force during 2025 (see paragraphs 4.19 to 4.53).

20. In July 2024, Defence transitioned LHD sustainment to the ‘Maritime Sustainment Model’, which involved the procurement and contracting of new commercial arrangements. Defence started the procurements later than planned, which limited the options available to Defence to manage issues and strengthen value for money outcomes during negotiations. Arrangements to manage probity were not robust and, in respect to the LHD Capability Life Cycle Manager procurement, probity was poorly managed. Defence has not benchmarked or established expected sustainment performance levels for the Maritime Sustainment Model (see paragraphs 4.54 to 4.83).

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.18

The Department of Defence ensures that appropriate arrangements are in place for its transition and remediation programs to improve the rigour with which these activities are managed, and provide assurance that the relevant objectives have been achieved.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.87

To support the future requirements for the LHDs, the Department of Defence develops and maintains class-specific life cycle sustainment plans for the Navy fleet, including funding requirements for the planned life of type, to ensure that the required capability is maintained across the classes’ whole of life, at a rate of agreed availability.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.6

The Department of Defence promptly reviews and updates, Navy’s Materiel Sustainment Agreements with the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group and Naval Shipbuilding and Sustainment Group, following significant changes in organisational structures, or at least every three years.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.31

The Department of Defence reviews and documents its LHD risk management arrangements, including the use of various ICT systems and oversight forums, with a view to identifying efficiencies, where possible, and ensuring that risks are appropriately identified, and actively managed with clear line of sight.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.69

Where the Department of Defence is notified of incidents such as suspected fraud or unethical conduct, the Department of Defence ensures that its response is fully documented and conforms to Defence policies and the Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.78

Where the Department of Defence’s contracts with industry include mechanisms to obtain assurance over the completion of activities under the contract and the performance of suppliers, the Department of Defence ensures that contractual mechanisms are implemented.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 4.13

The Department of Defence review the performance measures for the sustainment of the LHDs to support a more reliable and complete assessment of sustainment performance.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 8

Paragraph 4.63

The Department of Defence establishes arrangements to ensure that its internal policies for the establishment of appropriate probity processes commensurate with the size, scale and risk of its procurement activities are complied with.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 9

Paragraph 4.82

The Department of Defence benchmarks and monitors sustainment performance under the Maritime Sustainment Model to enable an assessment of the achievement of its strategic objectives.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

21. The proposed audit report was provided to the Department of Defence. Extracts of the proposed audit report were provided to BAE Systems Australia Pty Ltd, Babcock Pty Ltd, and Kellogg Brown and Root Pty Ltd. The Defence summary response is provided below and its full response is provided at Appendix 1. Responses from BAE Systems Australia Pty Ltd, Babcock Pty Ltd, and Kellogg Brown and Root Pty Ltd are provided at Appendix 1.

The Department of Defence acknowledges the findings contained in the Auditor General’s report on the sustainment of the Canberra Class amphibious assault ships.

Defence acknowledges that planning and procurement processes, sustainment management arrangements and performance monitoring and reporting were assessed as partly effective.

Defence supports the recommendations. Defence is committed to ensuring the through-life sustainment of the Canberra Class amphibious assault ships deliver the best possible capability outcomes for the Australian Government and the Australian Public.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

22. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Policy and program design

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Royal Australian Navy (Navy) amphibious warfare fleet includes two Canberra class amphibious assault ships, also known as landing helicopter docks (LHDs).2 These are HMAS Canberra, commissioned in November 2014, and HMAS Adelaide, commissioned in December 2015. The role of the LHDs is to provide Australian Defence Force (ADF) capabilities in amphibious warfare, humanitarian assistance, disaster relief and sea-lift and to contribute to broader naval activities.3 Effective sustainment of the LHDs, including maintenance and support, is essential for the effective delivery of these capabilities.

Key features of the capability

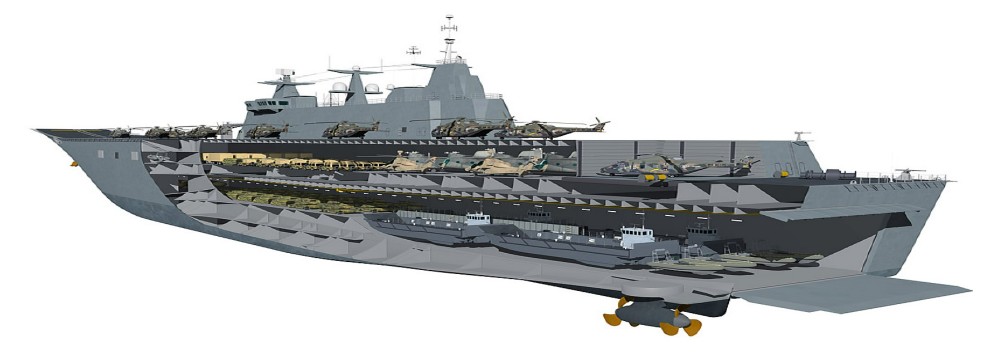

1.2 At 27,000 tonnes, the LHDs are the largest vessels in the Navy and are each intended to carry and embark over 1,000 personnel by helicopter and watercraft, with weapons, ammunition, vehicles and stores. The flight deck enables landing and transportation of helicopters, with vehicle decks able to accommodate up to 110 vehicles and 12 Abrams tanks. The LHDs also have medical facilities that include operating theatres, wards, x-ray, and dental facilities.

1.3 Each LHD is designed to carry and deploy four purpose-built LHD landing craft to transport personnel and equipment from the LHD ships to the shore without fixed port facilities.4 At a length of 23.3 metres, each landing craft has a displacement of 56.6 tonnes (light) and 110 tonnes (at full load).5 An image of equipment loaded on a Canberra class LHD is at Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Image of equipment loaded onto a Canberra class Landing Helicopter Dock

Source: Department of Defence.

Acquisition

1.4 Following a two-pass government approval process and limited tender involving two vendors, in 2007 the Department of Defence (Defence) contracted BAE Systems Australia Limited (BAE Systems) to build the two Navantia-designed LHD vessels and support systems.6 The LHD design was based on an existing Spanish ship (Juan Carlos) and incorporates the Australian Navy Combat System supplied by SAAB Australia Proprietary Limited. The total project budget for the LHD acquisition, including the 12 landing craft, was reported by Defence at $3.09 billion in June 2019.7

Sustainment arrangements

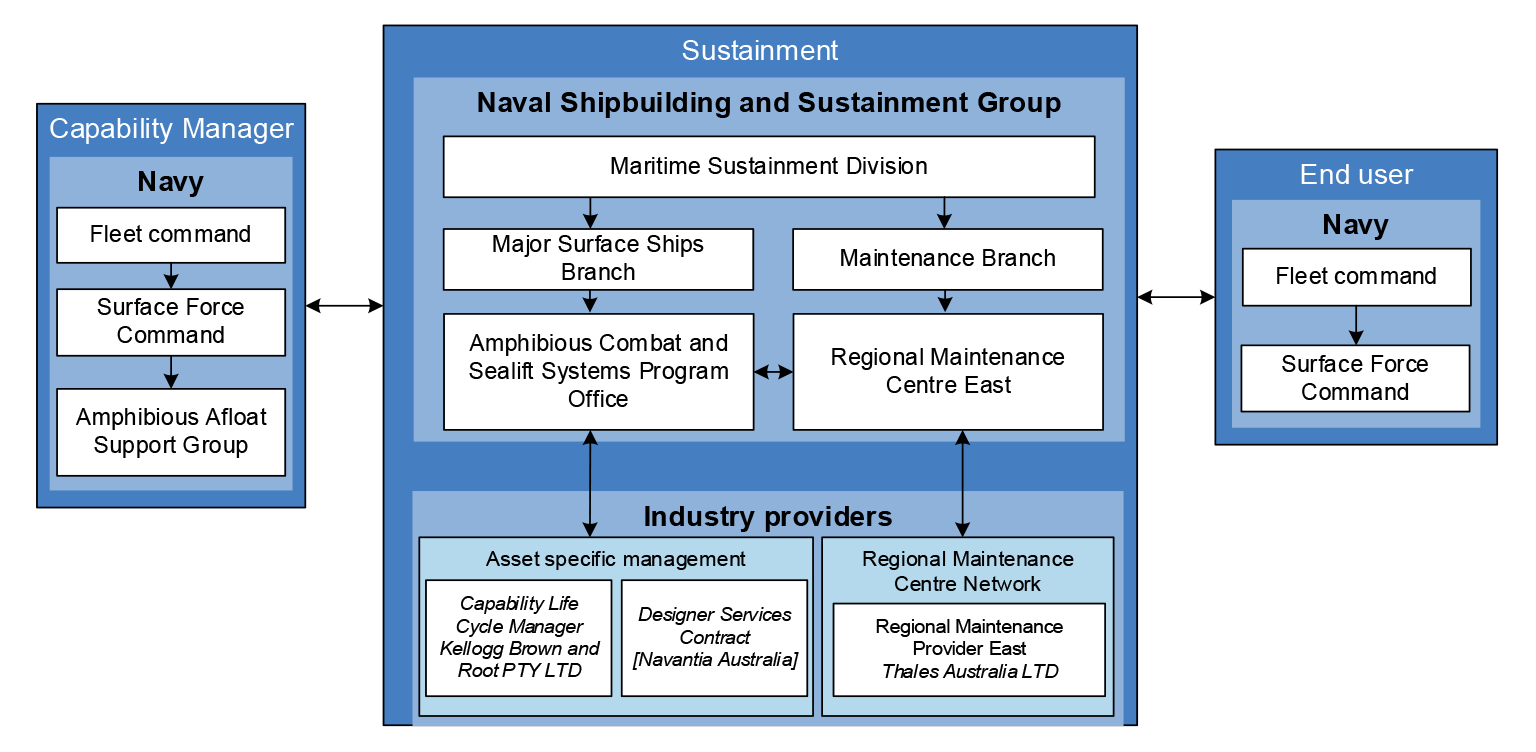

1.5 Since October 2022, Defence’s Naval Shipbuilding and Sustainment Group (NSSG) has been responsible for the sustainment of the LHDs and landing craft on behalf of the Navy in accordance with a Materiel Sustainment Agreement (MSA).8

1.6 Within the Maritime Sustainment Division of NSSG, the Amphibious Combat and Sealift Systems Program Office (ACSSPO) within NSSG is responsible for the delivery of materiel sustainment of Navy’s amphibious combat and support capabilities comprising of the LHDs, the 12 LHD Landing Craft, the Landing Ship Dock HMAS Choules and related shore-based facilities,9 principally at Fleet Base East, Garden Island, Sydney.

1.7 From July 2024, accountability for the execution of LHD maintenance activities transitioned from the ACSSPO to the newly established ‘Regional Maintenance Centre East’ under new organisational arrangements. ACSSPO retained accountability to ‘direct, govern and assure through life asset stewardship and seaworthiness’ of the LHDs (supported by industry providers), with the ACSSPO Director responsible under the MSA for the ‘design and delivery of effective sustainment services to enable the achievement of Navy’s outcomes’.

1.8 Figure 1.2 provides an overview of Defence’s sustainment arrangements for the LHDs, as of July 2024.

Figure 1.2: Defence’s sustainment arrangements for the LHDs from July 2024

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

1.9 Under the MSA, sustainment activities, including maintenance and engineering changes, are to be conducted in accordance with a continuous maintenance philosophy and a 60-month (five year) usage upkeep cycle. Planned and corrective maintenance is undertaken:

- during programmed external maintenance periods (6 to 8 weeks in duration, twice a year per ship), outside sea days; and

- through ‘organic level’ maintenance, typically performed on-board by Navy personnel, during sea days.

1.10 At the end of each five-year cycle, a docking for around 12 weeks is scheduled for the completion of major work, which may include work on the propulsion pods and propellers, bow thrusters, fin stabilisers, hull work and major engineering changes.

Sustainment contracting

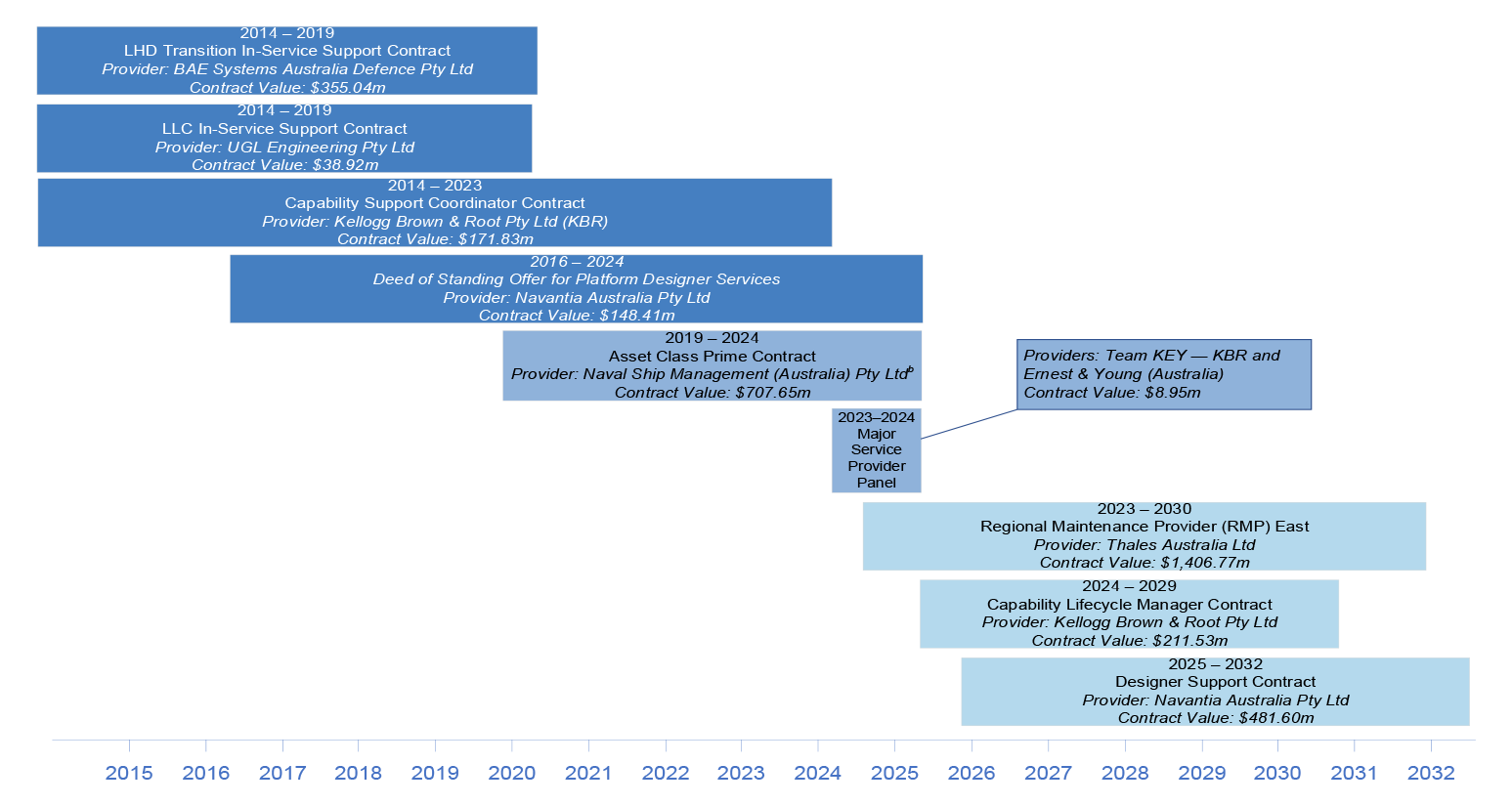

1.11 Since entry into service in 2014, Defence has contracted with industry for its core LHD sustainment delivery activities. Defence’s contracting model has changed from time to time, with each of the arrangements established at the commencement of the following three phases: the transition from acquisition to sustainment (from 2014 to 2019); the asset class prime contractor model (from 2019 to 2024); and the Maritime Sustainment Model (from 1 July 2024).

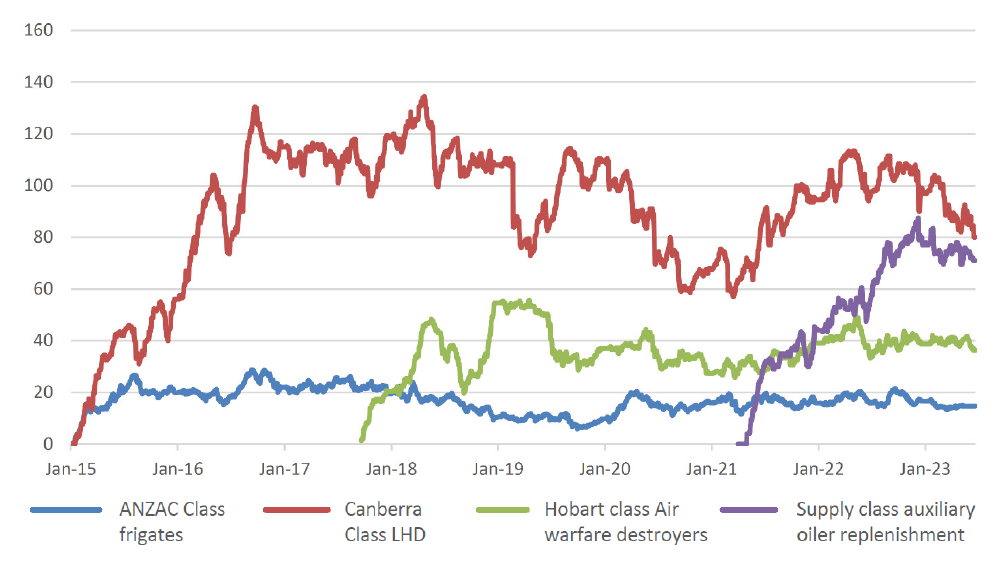

Figure 1.3: Key LHD sustainment contractsa

Key: ■ Phase 1: transition to sustainment — operational from November 2014 to June 2019 ■ Phase 2: asset class prime contractor sustainment contracting — operational from July 2019 to June 2024 ■ Phase 3: Maritime Sustainment Model — operational from July 2024

Note a: Contract value as at end of contract or at March 2025 (GST inclusive).

Note b: At the time of the procurement, NSM was a joint venture between UGL Engineering Pty Ltd (UGL) and Babcock International Group PLC (Babcock). On 18 February 2022, Babcock acquired the remaining 50 per cent shareholding in NSM.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

1.12 The LHDs are a ‘Top 30’ capability sustainment product for Defence.10 LHD sustainment has the fourth highest expenditure across all sustainment products in the maritime domain, with a funding provision of $180 million in 2024–25 (estimated at $1.9 billion to 2033–34).

Defence Strategic Review and other reviews

1.13 The Australian Government released a public version of the Defence Strategic Review (DSR) on 24 April 2023. Of relevance to the LHDs, the review stated that a ‘fully enabled, integrated amphibious-capable combined-arms land system’ is a key factor in the ‘ADF’s operational success’.11 The DSR recommended that an ‘analysis of Navy’s surface combatant fleet capability should be conducted in Q3 [Quarter Three] 2023 to ensure its size, structure and composition complement the capabilities provided by the forthcoming conventionally-armed, nuclear-powered submarines’.12 The DSR also recommended options be developed to change, streamline and accelerate the capability acquisition process for projects designated as strategically urgent or of low complexity.13

1.14 The Surface Combatant Fleet Review was provided to the government on 29 September 2023 and a public version of the review was released on 20 February 2024.14 This review outlined a future surface combatant fleet design to provide enhanced lethality and complement the planned introduction of conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarines.15

1.15 The government’s response to the DSR included the establishment of a new biennial National Defence Strategy (NDS), the first of which was released on 17 April 2024. The NDS stated that ‘[a]cross the coming decade, investment in the integrated, focused force will be extended to deliver increases in combat and enabling abilities’ in a number of capability priorities, including the:

amphibious capable combined-arms land system, enabled by Navy and Air Force combat capabilities and supported by Navy’s amphibious capability, to optimise the Army for littoral manoeuvre and control of strategic land positions, and to enable the ADF to undertake rapid stabilisation and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations.16

1.16 Further, in response to the DSR and the NDS, an updated Naval Shipbuilding and Sustainment Plan was released in December 2024.17 The plan stated that the LHDs:

will continue to provide the ADF with one of the most sophisticated amphibious operations capabilities in the world. In addition to deploying embarked forces, they can also conduct large-scale humanitarian and disaster relief missions.18

Previous audit coverage

1.17 Previous Auditor-General reports relating to naval procurement and sustainment, and of relevance to this audit include:

- Auditor-General Major Projects Reports 2008–09 to 2017–1819;

- Auditor-General Report No. 30 2018–19 ANZAC Class Frigates — Sustainment20;

- Auditor-General Report No. 44 2017–18 Defence’s Management of Sustainment Products — Health Materiel and Combat Rations21;

- Auditor-General Report No. 2 2017–18 Defence’s Management of Materiel Sustainment22;

- Auditor-General Report No. 9 2015–16 Test and Evaluation of Major Defence Equipment Acquisitions23; and

- Auditor-General Report No. 30 2014–15 Materiel Sustainment Agreements.24

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.18 In 2024–25, Defence’s sustainment activities for its fleet of two Canberra class amphibious assault ships, or LHDs, had a funding provision of $180 million (estimated at $1.9 billion to 2033–34). With service life-of-type until the mid-2050s, the LHDs provide Navy with amphibious capabilities which are to support the delivery of the Australian Government’s strategic intent through joint Australian Defence Force (ADF) deployments. This audit provides assurance to Parliament on Defence’s sustainment of naval capability, building on Auditor-General Report No. 30 2018–19 ANZAC Class Frigates — Sustainment.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.19 The audit objective was to examine the effectiveness of Defence’s sustainment arrangements for Navy’s Canberra class fleet of amphibious assault ships (or LHDs).

1.20 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Has Defence implemented fit-for-purpose planning and value for money procurement arrangements to support its sustainment activities?

- Has Defence effectively managed its sustainment contracts?

- Has Defence established appropriate performance monitoring and reporting arrangements?

1.21 The audit scope included examining the procurement of LHD sustainment services, the governance of procurement and sustainment activities, the management of sustainment contracts (primarily the Asset Class Prime Contractor contract), and performance monitoring and reporting.

1.22 The scope of the audit did not include Defence’s activities to procure the LHDs and landing craft, whether Defence appropriately managed outstanding build deficiencies, projects to enhance LHD capability (such as the SEA 2048 Capability Assurance Program, SEA 1442 Phase 5 Maritime Communications Modernisation, or SEA 1778 Phase 1 Deployable Mine Countermeasures Capability), or Defence’s management of ‘fundamental inputs to capability’ (such as the recruitment and retention of marine technicians and other specialists).

Audit methodology

1.23 The audit procedures included:

- reviewing Defence records, including procurement planning, tender assessments, advice to decision-makers, and contract management documentation;

- meetings with Defence personnel and Defence contractors;

- walkthroughs of Defence systems; and

- on-site fieldwork at Defence premises in Canberra and Fleet Base East within the Garden Island Defence Precinct in Sydney, where the LHDs are home ported.

1.24 The ANAO has co-operative evidence gathering arrangements in operation with entities. Defence advised the ANAO that it was unable to voluntarily provide certain information to the ANAO due to legislative restrictions on the disclosure of the information. In November 2023, ANAO officials exercised their delegation pursuant to section 33 of the Auditor-General Act 1997 to access information and be provided with documents. Defence provided the information and access to the required documents within the requested timeframe.

1.25 The audit was open to contributions from the public. The ANAO received and considered one submission.

1.26 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $1,274,000.

1.27 The team members for this audit were Mark Rodrigues, Megan Beven, Ciorsdan Daws, Steven Meyer, Lorraine Watson, Shane Madden, Ethan Carey and Amy Willmott.

2. Planning and procurement

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Defence (Defence) implemented fit-for-purpose planning and value for money procurement arrangements to support its sustainment activities for the Landing Helicopter Docks (LHDs).

Conclusion

Defence did not implement fit-for-purpose planning and value for money procurement arrangements to support LHD sustainment. Defence’s future sustainment requirements, including access to important intellectual property for the LHDs, were not sufficiently developed during the acquisition phase. Establishment of the sustainment arrangements was delayed, occurring during the transition to sustainment process and alongside remediation activities to address issues persisting from acquisition. Defence’s remediation activities did not achieve the required outcomes, resulting in additional work being transferred to the sustainment phase or managed as part of capability improvement projects.

Value for money and the intended sustainment outcomes were not achieved through Defence’s procurement processes. Early cost estimates for the sustainment of the LHDs were under developed and did not anticipate the impact of the protracted acquisition deficiencies extending into sustainment and continuing into 2025. Defence has regularly reviewed and adjusted its sustainment budget.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at improving Defence’s management of its remediation programs and ensuring class-specific funding requirements for military capabilities are developed and maintained on a whole of life basis.

2.1 The Defence Capability Manual25 applies to all major expenditure decisions taken by Defence, including major military equipment.26 The manual outlines four phases in the Defence capability life cycle, comprising the: strategy and concepts; risk mitigation and requirement setting; acquisition; and in-service (sustainment) and disposal phases. Defence’s 2007 Acquisition and Sustainment Manual, in place at the time of the acquisition of the LHDs, advised that planning for the transition of a platform into sustainment should commence early, in the requirement setting phase, and mature during the acquisition phase.

Did Defence appropriately manage the transition from acquisition to sustainment?

Defence accepted delivery of the ships from BAE in 2014 and 2015 later than planned and with defects and deficiencies in both vessels, many of which remain unresolved.

- In 2017, Defence established a Transition and Remediation Program (TARP) to manage the transition into sustainment and conduct the remediation work required to achieve the full capability expected from the LHDs. The remediation activities did not achieve all the intended outcomes and, in November 2019, Defence accepted the LHDs into full service with six ‘significant residual deficiencies’.

- In 2021, Defence established a capability assurance program to address urgent operational and safety issues for the LHDs, including issues carried over from the TARP.

- In July 2024, one quarter of the way through the planned life of the ships, Defence closed the acquisition project with significant defects and deficiencies from acquisition remaining unresolved and to be managed during the sustainment phase.

2.2 The acquisition phase for the two LHDs commenced when the Australian Government provided second pass approval on 19 June 2007 for $3,182 million (Budget 2007–08 out-turned). Defence’s advice to government stated that the total operating cost of the LHDs, including sustainment, was estimated at $1,349 million over the life of the ships.27 Details on the future sustainment arrangements for the LHDs were not provided to government in the 2007 advice.

2.3 Defence’s planning activities between 2010 and 2012 included developing the contracting arrangements for LHD sustainment services and establishing the LHD Systems Program Office (LHDSPO) in January 2011. Final operational capability was to be achieved in November 2016. The acquisition contract with BAE Systems was expected to end in 2015.28

Acceptance of the LHDs into service

2.4 The acceptance of HMAS Canberra and HMAS Adelaide from BAE to Defence was originally scheduled for January 2014 and August 2015, respectively. HMAS Canberra was delivered in October 2014 (a delay of eight months) with 6,640 defects and deficiencies, and HMAS Adelaide was delivered in October 2015 (a two-month delay) with 2,240 defects and deficiencies. As a result of the delay for the first LHD, Defence assessed that BAE owed the Commonwealth liquidated damages under the acquisition contract. In January 2015, a settlement was reached between Defence and BAE for in-kind services to be provided by BAE to Defence.29

2.5 The Chief of Navy approved the acquisition milestone of initial operational capability (IOC) for HMAS Canberra on 24 November 2015.30 Advice to the Chief of Navy included that, ‘[n]otwithstanding the success of IOC, issues remain that will require resolution as the capability progresses to FOC [final operational capability]’. These issues comprised ‘over 1000 residual defects and deficiencies’ identified within the ship’s communications system, radar system, combat management system, sewage system and integrated logistic support system.31 Following IOC, further issues were identified during Navy operational test and evaluation.32

Impact of acquisition issues on sustainment

2.6 The ‘Navy Capability Transition into Service’ guidance states that residual risks, ‘including known defects, deficiencies and shortcomings, plus as yet undiscovered latent defects’33 are to be managed as part of the transition into service. Impacts from these issues on LHD sustainment activities were documented in routine senior Defence internal reviews including Navy Fleet Screening reviews and Independent Assurance Reviews of LHD acquisition and sustainment.34 In March 2017, LHD sustainment was listed as an underperforming program on the Defence Product of Interest list ‘due to ongoing propulsion pod reliability and vibration concerns at delivery, as well as the concerns over maturity of the overall sustainment system’.35

2.7 A Seaworthiness Review Board meeting described as the defects and issues as, ‘in aggregate a critical seaworthiness risk’, for which ‘progress on remediation must be accelerated.’36 The board observed that Defence lacked ‘sufficiently defined policies, systems and processes needed to translate transition theory or aspirations into practice’ and called for a new framework in CASG maritime transition policy. The board also observed Defence’s ‘acquisition centric management focus’ and stated that the ‘LHD project is an example where a lack of planning for sustainment and transition has generated chronic and systemic deficiencies’.

Revised transition into service plans

Transition and Remediation Program, 2017–2020

2.8 In April 2017 Defence established a Transition and Remediation Program (TARP)37 to remediate the LHDs and close the acquisition project. Issues covered by the TARP included warranty claims, engineering changes, condition of class issues, and latent defects relating to the propulsion pods, vibration, propeller corrosion and cavitation, anaesthetic gas, shore power and the integrated logistic support system.38

2.9 The cost of the TARP was estimated at $128 million in acquisition funding. A total of 755 defects and deficiencies were grouped into 31 TARP funded sub-projects across two remediation plans.39 Project activities were aligned to the high-level objectives of the TARP but not clearly defined in project documentation. This reduced the clarity over roles and responsibilities and created ambiguity as to which tasks were regular sustainment work and which were TARP activities.

2.10 Final materiel release, a key acquisition milestone, was approved on 18 October 2019 by the Head of Navy Capability, with Defence advising that work would continue on outstanding integrated logistic support system and materiel deficiencies.40 The approval documentation included a list of the 64 defects and delivery issues that remained unresolved41, an unsigned and undated TARP closure plan, and the summary-level achievements of the TARP.42 The documentation did not detail the extent to which its objectives were achieved, or the actual costs of the program to date.

Achievement of final operational capability

2.11 The Chief of Navy approved final operational capability for the LHDs on 5 November 2019, with the following six ‘significant residual deficiencies’ to be managed during the in-service phase.43

- Propulsion pod vibration.44

- Insufficient physical space in the medical facility to enable the compliant configuration of the contractually required 34 beds.

- Noise in accommodation and compartments.

- Ongoing issues with the integrated logistic support system.

- Insufficient explosive ordnance magazine capacity.

- Issues with the sewage treatment plants.

2.12 Defence notified the Minister for Defence on 5 November 2019 that final operational capability had been achieved but with significant deficiencies that would remain ongoing. Defence advised that ‘[t]hese deficiencies, their impacts on capability and sustainability, and their ongoing remediation strategies have been addressed and are being managed.’

2.13 Updates on Defence’s management of these deficiencies have been provided by the ANAO in the Defence Major Projects Reports (MPRs). Of those six deficiencies:

- two — propulsion pods and integrated logistic support system — were reported by Defence in December 2021 as ‘being rectified’45;

- two — hospital bed configuration and noise in accommodation compartments — were transferred to the ‘LHD acquisition upgrade project’ (Capability Assurance Program); and

- two — sewage treatment plants and magazine capacity — were transferred to sustainment.46

Capability Assurance Program, 2021 to 2024

2.14 In March 2021, government provided first pass approval for $60.4 million (MYEFO 2020–21 out-turned) for the first tranche of work under the Capability Assurance Program (or SEA2048 Phase 6) for the LHDs.47 The program’s activities comprised of 41 tasks in total, some of which had been transferred from the predecessor program, the TARP (which closed in September 2020). The first tranche of work was to cover urgent operational and safety issues as priority tasks and the initial planning work for the capability assurance activities.

2.15 The scope and schedule of the Capability Assurance Program was reset by Defence in 2022 to include additional issues.48 In August 2023 an Independent Assurance Review into the Capability Assurance Program concluded that the first tranche of work, as approved in March 2021, would not be delivered as the priority tasks had not progressed beyond the design stage. The Independent Assurance Review also stated that:

[t]he complete list of capability assurance tasks has been de-scoped and re-prioritised, and there is insufficient schedule and budget remaining from the $60m approved at First Pass to complete the designs for all tasks, with some designs now needing to be funded at Second Pass.49

2.16 In November 2023, Defence’s Investment Committee delayed a number of capability assurance activities by two years due to the reprioritisation of Defence funding following the Defence Strategic Review. Navy was tasked with reporting back to the Investment Committee on how LHD sustainment funding could be prioritised for assurance program activities. In April 2024, government approved a further $65 million to progress the project.

2.17 Case study 1 provides an example of how Defence has managed a group of issues related to the LHD medical facility (Primary Casualty Reception Facility).

|

Case study 1. Remediation of the medical facility |

|

The delivery of health support services through the medical facility is a key capability provided by the LHDs and is of high mission criticality for evacuation and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief activities. In January 2015, Defence evaluated the operational condition of HMAS Canberra’s medical facility. As a result, a number of issues were identified, with short-term (within six months) and longer term (greater than six months) remediations recommended to address the issues. In 2016, work was undertaken to better understand and remediate the ongoing deficiencies — some of which had resulted in limitations being imposed on LHD activities. In April 2017, this work became part of the Transition and Remediation Program (TARP, see paragraphs 2.8–2.10). The scope of the TARP included the following issues:

When final operational capability was achieved in November 2019, the medical facility was included as one of six ‘significant residual deficiencies’ due to the limited physical space available between the beds. The number of beds in the facility was reduced from eight to five to provide 1,600 millimetres between each intensive care bed and 1,000 millimetres between each high dependency bed. The revised configuration resulted in facility not meeting the original requirements for patient capacity in the critical care wards. When the TARP was closed in September 2020, and after a vibration reducing system (approved for use on critical care beds) had been installed, the medical facility remained impacted by excessive vibration. This vibration was addressed in all but two areas of the ship once new four-bladed propellers were installed in 2021.a This TARP medical facility work was among those transitioned to the Capability Assurance Program (see paragraph 2.14 to 2.16). Other detailed costing and design work was also to be completed under the program. The first phase of the Capability Assurance Program did not progress as planned, and adjustments were made to Defence’s requirements between 2021 and 2023. In April 2024, government approved a further $65 million to address critical safety issues and bring the LHDs up to a ‘minimum viable capability’. This approval did not include the work required to remediate the facility, which had an estimated cost of $5 million. At October 2024, a number of issues remain unresolved and the medical facility continues to operate with limitations (refer to paragraphs 4.26 to 4.29 for further discussion of operational limitations). |

Note a: Defence advised the ANAO in June 2025 that the new propeller could only be installed when the LHDs were in dry dock, which occurred after the TARP was closed.

Recommendation no.1

2.18 The Department of Defence ensures that appropriate arrangements are in place for its transition and remediation programs to improve the rigour with which these activities are managed, and provide assurance that the relevant objectives have been achieved.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

2.19 Defence agrees to the recommendation.

Project closure

2.20 A second deed of settlement was negotiated with BAE Systems and Navantia, releasing the parties from all claims and actions.50 The acquisition project was then closed in July 2024, five years after final operational capability was declared in 2019.

2.21 Under the settlement deed: BAE Systems agreed to provide in-kind labour support and outstanding work, to be conducted within five years; and Navantia undertook to provide discounts on LHD support and outstanding work.

Did Defence conduct compliant and effective procurement for sustainment activities?

The integrity of Defence’s procurement processes for the LHD sustainment prime contractors was undermined by poor controls over probity risks.

- In 2014, the Capability Support Coordinator contract was awarded following an open tender process. The effectiveness of this procurement was limited by issues in the planning and evaluation processes. There were also shortcomings in the subsequent extension of the services with the incumbent provider under the Major Service Provider Panel following an unsolicited proposal in 2022.

- In 2014, the Transition In-Service Support Contract was awarded following a ‘collaborative’ sole source procurement process involving protracted engagement by Defence to improve an under-developed tender response. The procurement outcome did not demonstrate value for money.

- In 2018, the Asset Class Prime Contractor was awarded following a two-stage selection process which involved assessments against fit-for-purpose evaluation criteria. The integrity of the process was compromised by the departure of a senior Defence official with early involvement in the procurement who was then employed by, and negotiated with Defence on behalf of, the winning tenderer.

2.22 Defence’s procurements for its LHD sustainment activities were informed by a number of strategic reviews undertaken progressively between 2009 and 2017. These reviews led to a series of reforms to Defence’s Systems Program Offices (or ‘SPOs’), largely stemming from the Rizzo Review in July 2011 and the First Principles Review in April 2015.51

Phase 1: Interim arrangements for the transition to sustainment

2.23 By late 2011, Defence’s proposed strategy for contracting LHD sustainment services involved open tender processes and establishing performance-based arrangements, with multiple contractors. One of those contractors — the in-service support contractor — was to be primarily responsible for the implementation of sustainment activities. Another prime contractor — the Capability Support Coordinator (CSC) — was intended to be a ‘key partner’ to Defence, providing asset management expertise and overseeing the work of Defence’s other contractors.

2.24 Since at least 2011, Defence was aware through its industry engagement activities that the acquisition prime contractor, BAE, was planning to tender for the LHD sustainment procurements. In this context, where a potential service provider holds an existing relationship with Defence, attention to probity is particularly important to ensure the integrity and effectiveness of the procurement. An LHDSPO probity plan was approved in May 2011 and procurement-specific probity plans were approved on 8 June 2012 for the CSC and 26 July 2013 for the TISSC (as discussed at paragraph 2.57).

Reviews and revisions of the contracting model

2.25 Reviews of Defence’s major programs, capital projects, and sustainment products known as Gate Reviews and Independent Assurance Reviews, have been undertaken since 2009.52 At least 13 gate/assurance reviews examining aspects of the LHDs were conducted between 2011 and 2023. Six of those reviews addressed Defence’s sustainment arrangements.53

2.26 In 2011 a gate review found that the development of the tender documentation for LHD sustainment contracts had started later than necessary and it was unlikely that services providers would be in place in time for acceptance of the first LHD. A further gate review of LHD sustainment was conducted on 30 April 2012.54 This review was compromised because Defence did not implement its arrangements to manage probity risks. On 16 April 2012, two external members of the review board met with BAE and heard of BAE’s interest in LHD sustainment contracts.55 On 23 April 2012, BAE provided Defence a ‘discussion paper’ as ‘an industry input for the gate review process’ following its offer to a third board member (the Deputy Chief Executive Officer of the Defence Materiel Organisation). The discussion paper was considered within Defence to be an unsolicited proposal and was circulated to the review board members on 26 April 2012.

2.27 The BAE proposal highlighted the risks associated with a change of provider and recommended that Defence delay its planned procurements to adopt an interim strategy instead, where BAE would perform the functions of the CSC and maintenance contractors until the end of the LHD warranty period.56 Defence did not handle the unsolicited proposal in accordance with its procurement guidance in place at that time.57 The LHDSPO probity plan required Defence representatives to receive a probity briefing prior to any meetings with potential tenderers and to provide advance notice of any such meetings to the Chief Contracting Officer.58 The LHDSPO officer responsible for the procurement was not notified in advance of the meeting with BAE and the review board members were not probity-briefed.

2.28 The gate review concluded that Defence’s proposed procurement strategy was ‘unachievable’ and there were ‘significant challenges’ to overcome to establish the required LHD sustainment arrangements. The board did not endorse Defence’s proposed approach and instead recommended adopting a ‘fall back strategy’ to ensure a minimum level of sustainment capability at handover of the first LHD. This involved procuring a CSC contractor with a reduced scope and placing responsibility for LHD sustainment and other support tasks with BAE as an interim arrangement. The BAE proposal was not referred to in the gate review report.

2.29 While the risks associated with the interim arrangements were not explored in depth, the review board considered it to be the ‘only viable way forward’.59 The LHDSPO examined and documented the risks in more detail on 3 May 2012, after the gate review. A number of ‘medium to high’ risks were identified, including: a lack of competitive pressure on BAE in a sole source approach; and limited incentive for BAE as the acquisition contractor to adequately test the acquisition deliverables.

2.30 The sustainment strategy was updated and approved in September 2012 to reflect the interim arrangements. Consistent with BAE’s unsolicited proposal, the strategy covered a five-year period incorporating the warranty periods of both vessels from 2014. Two key LHD sustainment contracts were to be established: the CSC contractor; and a Transition In-Service Support Contract (TISSC). The two procurements were conducted in parallel over a 24 month period in 2013 and 2014, alongside other LHDSPO procurements.60

Capability Support Coordinator (CSC) contract

2.31 The CSC was to provide Defence with independent assurance services over the work of the prime contractor for the period of the TISSC and the preliminary stages of the follow-on ‘Asset Class Prime Contractor’ contract. The CSC contract was for ‘above the line’ services, meaning CSC staff would be embedded within the LHDSPO alongside Defence personnel.61 The independence of the CSC from other contractors was a key feature of the sustainment model selected by Defence.62

Planning for the CSC procurement

2.32 Defence adopted a two-stage approach for the procurement, comprising an initial request for tender process followed by an ‘Offer Definition Activity’ phase. An open approach to market was approved by the delegate on 24 January 2013. Defence opened the CSC RFT to the market on 25 February 2013, the same day that its legal advisor (Ashurst Australia) provided comments on an incomplete draft. As a consequence, the tender was not fully developed at the time it was issued, compromising the effectiveness of the process. Unresolved risks identified by Ashurst included: the significant risk arising from third party intellectual property arrangements for disclosure restricted entities63 and the lack of a clear statement on the services to be provided under contract. Ashurst noted that ‘unless there is a clear statement in the [conditions of contract] as to the different types of Services to be provided, there will be confusion, dispute between the Contractor and Defence and the risk of real uncertainty in the administration of the Contract’.

2.33 These risks became issues during the tender period. The original closing date of the RFT, 29 April 2013, was extended to 13 May 2013 and at least 41 changes ranging from minor to substantive were made to the tender documentation.64 Substantive changes included the addition of an appendix with Australian Industry Capability Plan requirements and amendments to the third party intellectual property provisions of the tender documents.

2.34 The disclosure restricted entity provisions were required due to Defence’s contractual obligations to the LHD acquisition contractors (BAE and SAAB, or ‘Interested Parties’) to prevent the release of sensitive intellectual property to specified commercial competitors. In February 2013, Ashurst advised Defence that ‘the proposed arrangements’ in the RFT gave ‘the Interested Parties with a large degree of control over who may be considered for the role of CSC’. To address this issue, Defence required disclosure restricted entities to provide a letter of consent from the nominated interested parties granting access to the relevant intellectual property and information.

2.35 On 28 March and 15 April 2013 two tenderers contacted Defence to advise that they were unable to obtain the letters of consent, effectively excluding them from tendering on the CSC. On 16 April 2013 Defence released an addendum removing the prohibition of an interested party from being a subcontractor to CSC tenderers and providing a two-week extension to the tender closing time.

2.36 The tender evaluation plan was finalised on 8 May 2013. The plan stated that tender responses would be assessed against seven unweighted criteria and ranked by order of merit. The results were to inform a value for money assessment conducted by the tender evaluation board and the formulation of recommendations to the delegate.

Evaluation against criteria

2.37 Six responses were received by the close of tender on 13 May 2013 and each were assessed as compliant in the initial screening process by 17 May 2013. Three separate tender evaluation working groups undertook detailed commercial, technical and financial evaluations of tenders between 16 May to 23 July 2013. The tender evaluation board (comprising nine members, including each of the working group leads) convened at least 10 times between May and July 2013.

2.38 The evaluation criteria listed in the evaluation plan included an additional sub-criterion for the financial evaluation that was not included in the RFT documentation or subsequent addenda.65 The financial TEWG evaluation was, however, limited by the extent of information made available to the tenderers in the RFT. The RFT specified Defence’s budget and required tendered cost rates to be within that budget cap. This reduced the TEWG’s level of confidence in the proposed pricings offered. The TEB agreed that the price estimates provided by the tenderers could not be taken into account.

2.39 The commercial and financial TEWGs recommended all six tenders proceed to offer definition phase and the technical TEWG recommended that four proceed.

2.40 The tender evaluation board decided that two of the seven evaluation criteria — the ‘technical competence’ and ‘trusted advisor’ criteria — were ‘critical to the successful delivery of CSC services’ and the greatest area of differentiation between tenders. On this basis, the board recommended, and the delegate approved (on 23 July 2013), the two tenderers with the highest scores against the two priority criteria progressing to the offer definition phase. This approach represented a departure from the published tender process by placing greater importance on two criteria from a total of seven. The seven criteria were not weighted and were to have equal importance.

Management of probity issue

2.41 In January 2013, a Navy reservist working part-time on the ‘Rizzo Reform Program’ contacted the LHDSPO to advise that he had been approached by a tenderer to help develop their tender for the CSC. The tenderer formally contacted Defence on 4 March 2013 requesting written confirmation that engaging this official would not cause a conflict of interest. After seeking advice from the Australian Government Solicitor (AGS), the procurement’s legal process/probity advisor, Defence responded on 6 March 2013 advising that there was no conflict of interest.

2.42 In November 2013, after the tenderers had been selected for the offer definition activity, Defence revisited its consideration of the potential conflict of interest in the context of the offer definition stage of the procurement. Between November 2013 and January 2014 Defence engaged with both the AGS and the tenderer on the matter. Defence was advised by AGS that the continued involvement of the particular official represented a number of risks. The LHDSPO provided an update to the AGS on 30 January 2014, advising that it was still considering ‘the best approach’ to close the issue out. Defence did not request that the official be removed from all further involvement with the offer definition activity process.

Offer definition activity

2.43 The proposed offer definition activity process and documentation was reviewed by the legal advisor (Ashurst Australia) and the probity advisor (AGS) between July and August 2013, with approval provided on 5 and 15 August 2013 respectively. The offer definition activity documentation contained amendments to the CSC RFT, including the conditions of contract and statement of work. This was not aligned with Defence’s procurement guidance in place at the time, which set out that offer definition activities are to be used to enable ‘Defence to better assess the extent to which shortlisted tenderers are able to meet Defence requirements’. The guidance did not provide for offer definition activities to amend Defence requirements as set out in the RFT or for the provision of revised tenders.

2.44 A gate review conducted on 30 August 2013 documented concerns about potential ‘overlaps or gaps’ in the different LHD sustainment contractors’ roles and concerns that the CSC ‘could grow to be a significant “in-sourced” organisation’. The board recommended that the LHDSPO ‘review and refine the sustainment strategy’ under the direction of the delegate.

2.45 On 18 September 2013, Kellogg Brown and Root (KBR) and one other tenderer were invited to participate in the offer definition activity. On 27 September 2013, the delegate provided guidance to the LHDSPO to adopt a ‘lean SPO’ model consisting of no more than 50 staff, including CSC personnel. Further delegate direction included transferring some of the proposed functions of the CSC to the TISSC.

2.46 In early October 2013, Defence sought advice from the AGS on the probity considerations of the potential changes to the scope of the TISSC and CSC procurements.66 After an iterative review process with the AGS, further amendments were made to the RFT to provide Defence with greater flexibility to vary the scope and volume of services under the CSC. Other amendments included focusing the CSC role on maintenance monitoring rather than maintenance management, and limiting core staff to 50 people.

2.47 AGS provided ‘legal process sign-off’ for the revised proposed offer definition activity process on 12 November 2013. Defence did not seek legal clearance from Ashurst for the revised RFT. Ashurst’s sign-off in August 2013 for the offer definition activity documentation recorded a range of caveats and risks arising from ‘the substantial amendments to the RFT’.

2.48 The offer definition activity documentation was issued to the two tenderers on 12 November 2013. Responses from both tenderers were received by 16 December 2013. Following further assessment against the evaluation criteria, the offer definition evaluation confirmed the original tender evaluation board assessment that ranked KBR first. Defence conducted contract negotiations with KBR between 26 March and 14 May 2014.

2.49 On 14 June 2014, Defence briefed its Minister on its selection of KBR as the CSC noting that the total cost excluding profit of $48 million was significantly lower than the Commonwealth expenditure cap of $66 million, as a result of a competitive tender process and ‘some reduction in scope’ which was not defined in the advice. On 18 June 2014, the delegate approved the selection of KBR under Section 44 of the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) for an estimated contract value of $72.37 million.67 The CSC contract was executed on 20 June 2014 with an initial term of five years, with the option to extend for no less than 12 months and no more than four years.

Extension to the contractual arrangement

2.50 To determine whether an extension would be granted for the CSC contract, Defence was to undertake an ‘extension review’ by assessing the contractor’s performance against the criteria in the CSC contact. 68 Defence reviewed KBR’s performance in April 2019 and on 15 May 2019 extended the contract by four years to 30 June 2023 for a total of $148.78 million. The contract was varied 26 times over its life and at the end of the contract in June 2023, the total value was $171.83 million.69

2.51 With no further options available to extend the CSC contract beyond 30 June 2023, a 12 month gap existed between the end of the CSC and the start of the successor arrangements in July 2024.70 In September 2022, Defence considered options to cover this gap through the Major Service Provider and/or the Defence Support Services standing offer panel arrangements but did not record a decision on its planned approach.

2.52 On 2 November 2022, KBR provided Defence with what it described as an ‘unsolicited proposal’ for the continuation of its services for 12 months to June 2024.71 The proposal was for services valued at $18.06 million for 38.15 full time equivalent (FTE) staff under Defence’s existing Major Service Provider (MSP) panel arrangements.72 Defence declined KBR’s proposal on 8 December 2022, advising that it had ‘decided to go in an alternate direction for above-the-line services after 30 June 2023’. However, on 20 February 2023 Defence advised KBR that a ‘future approach under the Major Service Provider (MSP) Arrangement may occur towards April of 2023’.

2.53 There is no record of Defence subsequently approaching the market through the MSP panel for these positions. Two days before the expiry of the CSC contract (on 28 June 2023), KBR services comprising 36.4 FTE staff were approved by Defence under the MSP panel arrangements for a total contract value of up to $11.34 million.

2.54 Defence advised the ANAO in August 2024 that it ‘did not establish specific arrangements for the management of probity for the procurement of KBR under the MSP panel following receipt of KBR’s unsolicited proposal.’ Defence’s management of probity in the context of the procurement process for the successor arrangements to the CSC is discussed further in Chapter 4, Case study 2.

Transition In-Service Support Contract

2.55 Consistent with the September 2012 updated sustainment strategy (discussed in paragraph 2.30), the engagement of BAE as the Transition In-Service Support Contract (TISSC or sustainment) contractor through a sole source process for $183.4 million was approved by the delegate on 24 January 2013. The intention of this approach was to leverage the ‘skills and experience’ of BAE as the acquisition contractor. The approval records stated that this approach had ‘the least schedule risk’ and that costs associated with two separate contractors for acquisition and sustainment would be reduced by having only one contractor for both.

2.56 Defence identified three ‘key risks’ for the sole-source approach, including a ‘lack of competitive pressure’ and ‘compromised short-term value for money’.73 The mitigation strategies listed for these risks in the approval records included:

- establishing a contract development agreement and agreed principles of behaviour with BAE;

- progressing alternate/fallback options to ‘maintain (an element of) competition’; and

- preparing a clear negotiation strategy with required outcomes and maintaining consistency in the strategy’s execution.

2.57 On 18 March 2013, Defence invited BAE to undertake ‘collaborative contract development’, which would involve both parties ‘working together to develop the draft TISSC provisions’. A contract development deed was executed on 29 April 2013, establishing the framework for BAE to work ‘collaboratively and cooperatively’ with Defence. Early consideration of probity, particularly for procurements with high levels of tender interaction, is important to support the integrity of the process. The probity plan for the TISSC procurement was approved around three months after the execution of the contract development deed, on 26 July 2013.74 As outlined at paragraph 2.26, Defence was aware of BAE’s interest in sustainment contracting from at least April 2012. The probity management arrangements established by Defence in 2013 did not support Defence’s early engagements with BAE.

2.58 Defence released the TISSC Request for Tender (RFT) to BAE Systems on 18 November 2013 and received a response from BAE on 16 December 2013. The tender was to be evaluated by three working groups reporting to a Tender Evaluation Board. During the first meeting of the evaluation board on 17 January 2014, all three working group leads raised ‘significant concerns over the extent of non-compliance in the BAE tender response.’75 The delegate was advised of these issues in writing on 24 January 2014 and was informed that ‘the BAE tender response significantly erodes the argument used to justify the original single supplier limited tender (sole source) procurement method’. ‘Critical issues’ identified by the tender working groups included the following.

- The BAE tender response does not fully reflect the collaborative discussions held in the latter part of contract development work under the Deed …

- At this stage, only five of the 13 endorsed TISSC Principles established by the Deed are likely to be achieved. …

- [The] requirement for sustainment contractor accountability and reduced transactions is at significant risk. The BAE response attempts to transfer significant accountability, transactions and risk back to the Commonwealth.

2.59 The tender evaluation was suspended to enable BAE to resubmit its tender. A revised tender was submitted by BAE on 11 March 2014. Defence’s June 2014 evaluation of the revised tender stated the following.

Overall, the BAES tender contains significant deficiencies and risks that taken together prevent the TEB from determining, at this stage, that the contract constitutes value for money. However, BAES have indicated an acceptance of the requirement to address underlying non-compliances.

2.60 The Tender Evaluation Board recommended that Defence continue ‘collaborative development’ with BAE to: address the remaining non-compliances and areas of high and extreme risk; and resolve the underlying value for money weaknesses.

2.61 Contract negotiations took place between 14 and 28 August 2014. The negotiated outcome was approved by the delegate on 15 September 201476, providing up to $215.6 million for the contract with BAE as the TISSC service provider. Defence did not obtain probity advice or clearance during the TISSC procurement.77 In advice to the delegate regarding the significant non-compliances and risks, Defence stated the following.

Resolving these issues has been a protracted process involving an extension to the original tender period, and a more comprehensive collaborative effort to improve Commonwealth’s confidence and reduce uncertainty.

2.62 The advice to the delegate did not address whether the additional collaborative discussions had resolved the deficiencies listed in the value for money assessment in the June 2014 tender evaluation report. The advice did not mention the concessions made by Defence on base profit during negotiations, as detailed in the contract negotiation report.

2.63 On 29 August 2014, Defence advised its Minister of its finalisation of negotiations with BAE, at a price of approximately $220 million over four years. In contrast to its brief on the CSC selection (refer to paragraph 2.49), Defence did not inform the Minister that the contract value exceeded the approved cost of $183 million. Defence entered into the TISSC on 26 September 2014, and the operative date was achieved on 15 December 2014 upon acceptance of the first LHD. The initial contract value was reported on AusTender as $185.56 million for a four year term.78 Defence records indicate that there were 20 variations to the contract, including one in February 2018 to extend the contract term by 12 months. Financial approvals under section 23 of the PGPA Act for the last three variations were either not retained by Defence or not signed by the delegate. These variations included the cost settlements (or true-ups) for the final two financial years. As at 5 June 2024, a total contract value of $355.04 million was reported on AusTender.

2.64 In October 2017, Bechtel was engaged to conduct a review of the LHDSPO commercial arrangements. Among other things, the report concluded that the original decision to sole source the TISSC to BAE was a valid mitigation for transition issues but ‘the poor performance by BAE [had] negated this decision.’ The poor performance involved: insufficient and inadequately skilled resources; lack of planning for works, such as the procurement of required parts for external maintenance periods; and a failure to use Defence systems.79

2.65 The report stated that Defence had not exercised its contractual rights and had instead stepped in to perform work on behalf of BAE.80 It was also reported that in some instances, Defence had ‘provided cost relief for poor performance’ by allowing BAE to delay work that had not been completed on time until the ships’ next availability (irrespective of whether delays to that work were caused by Defence or BAE). A May 2017 Defence Seaworthiness Board report had raised similar concerns, summarising the reason for the performance issues as follows.

In reality two very separate arms of BAES Corporation have taken on Acquisition and Sustainment and the expected transfer of corporate knowledge to provide for a smooth transition has not eventuated.

Phase 2: LHD Asset Class Prime Contractor

2.66 On 21 March 2018, Defence approved a procurement strategy for the selection of a new LHD sustainment contractor. Under these new arrangements, the in-service support sustainment contracts were to be consolidated under a single Asset Class Prime Contractor (ACPC) covering the LHDs and LLCs. The strategy also envisaged a reduced dependence on the CSC contractor over time.

2.67 The approach to market was approved on 12 March 2018 for an estimated value of $2.02 billion (GST inclusive) over a 15-year period. The advice to the delegate reported that one benefit of a 15-year contract was ‘to obtain the return on investment made in changing the SEM [Supplier Engagement Model]’. The approval outlined a two-stage procurement process involving:

- Stage 1: Invitation to Register Interest (ITR) to shortlist respondents; and

- Stage 2: Collaborative Requirements Definition Activities with down-selected respondents prior to the release of a restricted Request for Tender (RFT) and evaluation.

2.68 The external probity adviser for the ACPC procurement (Sparke Helmore) was engaged in March 2018.81 Under Defence’s probity plan, the LHDSPO was required to maintain a probity and conflict of interest register for the ACPC procurement. Entries for 167 personnel and contractors involved in the procurement were recorded in the register between July 2017 to November 2018. The register was not complete, with 109 (65 per cent) of individuals recorded as receiving a probity briefing, and 148 (89 per cent) completing a conflict of interest declaration. Of those 148 declarations, five potential conflicts of interest were reported.82

2.69 On 24 September 2018, four days before the RFT closure date, a conflict of interest was declared by a senior Defence official who was in active negotiations with NSM for a job opportunity they ‘were likely to take’. The official had contributed to the ACPC procurement process and relevant activities. Prior to this, the official had also been approached by NSM in May 2018 for information related to the ACPC procurement.

2.70 Defence determined that the offer of employment did not give rise to a conflict of interest, however on 26 September 2018, Defence prohibited the individual from any further participation in the tender activities. On 28 September 2018, the NSM tender response listed the senior Defence official, who was still employed by Defence, as one of NSM’s key personnel (the program director) if awarded the contract. In November 2018, this individual participated in Offer Definition Improvement Activity (ODIA) negotiations on behalf of NSM.83

2.71 NSM did not seek, and Defence did not provide, written approval for the inclusion of the individual in NSM’s tender response and ODIA negotiations as required by the Tenderers Deed of Undertaking for the RFT process, as executed by NSM. Additionally, when Defence became aware of the individual’s involvement, it took no action.

2.72 Defence published the ITR on AusTender on 23 April 2018. An initial industry briefing was held on 30 April 2018, followed by one-on-one industry briefing sessions held between 3 and 7 May 2018. The ITR closed on 11 June 2018, with six responses received prior to the closing date. After an initial screening of all responses, all six tenders were evaluated against the criteria in the tender evaluation plan approved in March 2018.84 On 5 July 2018, the Tender Evaluation Board (TEB) Chair approved the ITR evaluation report, which recommended that the three highest ranked tenderers be invited to participate in an RFT process.