Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management and Oversight of Compliance Activities within the Child Care Subsidy Program

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The Child Care Subsidy (CCS), which aims to improve access to early childhood education and care, cost the Australian Government $13.6 billion in 2023–24.

- Fraud and non-compliance reduces available funds for public goods and services.

- This audit provides assurance to Parliament on the effectiveness of the management and oversight of compliance activities within CCS by the Department of Education (Education) and Services Australia.

Key facts

- CCS supports 1.45 million children to attend approved care as of September 2024.

- Education is responsible for approving child care providers and services to access CCS. Providers deliver care via services, which can be Centre Based Day Care, Outside of School Hours Care, Family Day Care or In Home Care.

- CCS is paid directly to approved providers by Services Australia and passed on to eligible families in the form of fee reductions.

What did we find?

- The management and oversight of compliance activities within the CCS is partly effective.

- Governance arrangements are partly effective. Education’s oversight of CCS compliance activities in Services Australia is not sufficient.

- The approach to compliance activities is partly effective. Both entities have effective approaches to prevention, but deficiencies were identified in monitoring and enforcement arrangements.

What did we recommend?

- There were 7 recommendations to improve the management and oversight of compliance activities within the CCS — 4 to Education and 3 to both Education and Services Australia.

- Education agreed to all 7 recommendations, and Services Australia also agreed to the 3 joint recommendations.

$484.1 m

estimated lost to CCS non-compliance in 2023–24

299

provider and service cancellations by Education over 2022–23 and 2023–24

$318.2 m

estimated savings from compliance activities October 2022 to December 2024.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Child Care Subsidy (CCS) is administered by the Department of Education (Education) under the Family Assistance Law (FAL), to assist families to meet the cost of early childhood education and care.

2. At a cost of $13.6 billion in 2023–24, CCS is one of the ‘fastest-growing major payments’ of the Australian Government, with forecast average annual growth of 5.5 per cent over 2024–25 to 2034–35. As of September 2024, CCS supported 1.45 million children to attend approved care. This equates to 32.6 per cent of all 0 to 13-year-olds in Australia.

3. Education has policy responsibility for the CCS, including the CCS special appropriation. Services Australia is accountable for delivering payment and ICT services on behalf of Education, and for prioritising the service delivery within its budget appropriation.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. The CCS was estimated to be one of the top 20 expense programs in 2024–25. Australian Government spending on CCS was $13.6 billion in 2023–24, of which an estimated 3.6 per cent ($484.1 million) was lost to incorrect payments, including fraud and non-compliance. Fraud and non-compliance reduces available funds for public goods and services.

5. This audit was conducted to provide assurance to the Parliament over the effectiveness of the management and oversight of compliance activities within the Child Care Subsidy program. This audit was identified as a priority by the Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit in the context of the ANAO’s 2023–24 Annual Audit Work Program.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the management and oversight of compliance activities within the CCS program.

7. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level audit criteria were adopted:

- Have effective governance arrangements been established?

- Is the approach to compliance activities effective?

Conclusion

8. The management and oversight of compliance activities within the CCS is partly effective. Governance arrangements do not provide Education with whole of program oversight, and evaluation arrangements are only partly implemented. Although the payment accuracy rate improved in 2022–23 and 2023–24, and comprehensive prevention activities are in place, gaps in monitoring and enforcement are not being effectively managed.

9. Education has established partly effective arrangements to oversee CCS compliance activities. Committees accountable to a Senior Executive Service (SES) Band 2 within Education oversee its Child Care Subsidy Financial Integrity Strategy 2023–2027 (Integrity Strategy), which sets out its approach to risk based and data driven regulation of CCS providers and services, to be implemented from 2023 to 2027. To successfully complete its implementation of the Integrity Strategy, Education will need to improve its data quality in the Child Care Intelligence System (CCIS) and implement evaluation arrangements across the full suite of its compliance interventions.

10. Bilateral arrangements between Education and Services Australia are set out in a Statement of Intent and Program Delivery Services Schedule for Child Care Subsidy Program, which detail the objectives, governance, risk and issue management, roles and responsibilities and assurance obligations for CCS services. These arrangements do not provide Education with sufficient oversight of CCS compliance activities within Services Australia. Education has established a CCS Fraud and Corruption Risk Assessment (FCRA), but this is not supported by engagement with Services Australia over shared risks. Services Australia has not established a FCRA that includes CCS.

11. Education and Services Australia have established a partly effective approach to compliance activities. While Education and Services Australia have comprehensive arrangements to prevent non-compliance among providers and families respectively, deficiencies were identified in relation to monitoring, investigations and enforcement.

12. Services Australia is responsible for monitoring family compliance. It does not monitor non-employment activities, is unable to identify CCS-related matters within its tip-off data, and its income monitoring via the CCS reconciliation process is not consistent with the FAL, due to its reliance on lodged tax return data before a notice of assessment has been issued.

13. Education is responsible for monitoring provider compliance, and investigations and enforcement. It monitors whether providers continue to meet some conditions to administer CCS. It does not have assurance that all conditions are met, does not apply quality assurance across all monitoring and investigation activities, and does not investigate possible CCS provider overpayments identified while monitoring payment accuracy via the Random Sample Parent Check (RSPC). Its ability to effectively implement the Integrity Strategy is undermined by poor data quality in CCIS and a lack of cohesive enforcement strategy, which mean it is not able to assess whether decisions to take enforcement action are fair, impartial, consistent, or proportional.

Supporting findings

Governance arrangements

14. Education oversees CCS compliance activities via a Financial Integrity Governance Board (FIGB) and Financial Integrity Operational Committee (FIOC), that are accountable to the responsible SES Band 2. Education does not have visibility of compliance activities or risk management in Services Australia. Bilateral arrangements between the Department of Education and Services Australia are set out in a Statement of Intent between the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Services Australia and the Secretary of the Department of Education (Education Secretary). Under the Statement of Intent, the Program Delivery Services Schedule for Child Care Subsidy Program details the objectives, governance, risk and issue management, roles and responsibilities and assurance obligations for CCS services. These do not provide sufficient oversight of CCS compliance activities. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.26)

15. Education’s Integrity Strategy documents its approach to risk based and data driven regulation to be implemented from 2023 to 2027. To successfully complete its implementation of the Integrity Strategy, Education will need to improve its CCIS data quality. Although Services Australia’s annual CCS risk management plans document its approach to managing risk in the program, including compliance risk, there is no documented approach (either in Education’s Integrity Strategy or via Services Australia’s own program documentation) that provides strategic direction or describes how risk and data inform decision-making regarding Services Australia’s CCS compliance activities. Education has established a CCS FCRA, although information about the purpose, implementation status, and timeframes of risk treatments is not included. Risk identification, analysis and evaluation within the FCRA is not supported by engagement with Services Australia over shared risks. Services Australia has not established a FCRA that includes CCS. (See paragraphs 2.31 to 2.52)

16. Education monitors the effectiveness of the Integrity Strategy using payment accuracy data drawn from the RSPC and reporting against budget savings measures. As of March 2025, evaluations of compliance interventions have been planned but not yet implemented across the full suite of compliance interventions. Initial intervention evaluations and resulting adjustments for each team are due to be completed in 2025. As such, is not possible to effectively measure the impact of activities undertaken under the Integrity Strategy, or understand the relative contributions of different types of activities. (See paragraphs 2.53 to 2.70)

Approach to compliance activities

17. CCS program design, including the legislative framework administered by Education, has been strengthened to support compliance. Access to the program is managed via provider and individual application processes by Education and Services Australia respectively. Both entities provide appropriate information to stakeholders via a range of sector guidance, communications and advice. Education engages regularly with sector representatives and has commenced work to improve the capability of Family Day Care (FDC) providers to comply with their obligations under the FAL. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.19)

18. Education and Services Australia monitor family and provider compliance with the FAL using family income, sessions of care information from providers, electronic funder transfer (EFT) provider audits, and manual checking of provider reporting. These controls focus on incorrect session reporting resulting in incorrect payment. Education does not have assurance that certain other requirements, such as fit and proper person requirements, are met after initial CCS approval has been granted. Where non-compliance is suspected, Education may choose to conduct an administrative or criminal investigation. Services Australia’s use of data for checking family income is not consistent with the FAL, and there are deficiencies in Education’s record keeping, monitoring of ongoing provider and service eligibility for CCS, and quality assurance arrangements in both EFT provider audits and investigations. Services Australia’s collection of tip-off information does not effectively support the identification of CCS matters. (See paragraphs 3.22 to 3.62)

19. Education imposes fines, debts, conditions on approval, suspension and cancellation of approval, and refers matters for criminal prosecution as part of its work to enforce compliance with the FAL. Education does not have a policy to guide decisions on whether, and in what circumstances, to take enforcement action, and enforcement strategy has not been considered by the FIGB. Without cohesive policy guidance for staff, Education is unable to assess whether decisions to take enforcement action are fair, impartial, consistent, or proportional. From 2022–23 to 2023–24, across the CCS, Education withdrew $473,010 (42.2 per cent of the total $1.1 million) of fines issued, raised and recovered 11 compliance-related debts valued at $59,648 (0.9 per cent of the total $6.4 million) and identified but did not investigate 970 potential overpayments with a total value of $106,375. (See paragraphs 3.63 to 3.80)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.22

The Department of Education and Services Australia review and revise arrangements giving effect to the Statement of Intent and subordinate documents to ensure sufficient oversight of shared regulatory activities is provided.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Services Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.62

The Department of Education strengthen its approach to implementing evaluation of the effectiveness of compliance interventions, to cover all interventions in the Child Care Subsidy Financial Integrity Strategy 2023–2027.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.68

The Department of Education, in consultation with Services Australia:

- develop a program-level CCS compliance and enforcement strategy including:

- approaches to coordination;

- governance;

- risk management;

- reporting between the entities;

- reporting of savings outcomes against targets; and

- performance and impact measurement, review and evaluation.

- ensure a version of the strategy is published on each entity’s website.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Services Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.28

Services Australia work with the Department of Education to review and revise its arrangements for collecting and reporting information about Child Care Subsidy compliance-related matters, including tip-offs, risk assessments and controls, and investigations, to ensure sufficient information is provided to the Department of Education to oversee compliance activities.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Services Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.61

The Department of Education review whether its electronic investigation management system (EIMS) is fit for purpose and enables staff undertaking compliance related work to meet all requirements of legislation.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.73

The Department of Education seek independent legal advice from the Australian Government Solicitor regarding its obligations (under the Family Assistance Law and other relevant legislation such as the Privacy Act 1988) in respect to possible Child Care Subsidy provider overpayments identified while monitoring payment accuracy using the Random Sample Parent Check.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 3.79

The Department of Education update operational policies and procedures to:

- improve compliance related record keeping;

- ensure quality assurance and review arrangements are in place across relevant teams; and

- establish program-level investigations and enforcement policies to support fair, well documented, consistent, and proportional decision-making, and conflict-of-interest management.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

20. The proposed audit report was provided to the Department of Education and Services Australia. The summary responses are reproduced below and the full responses are at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

Department of Education

The Department of Education (the department) acknowledges the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) performance audit on the management and oversight of compliance activities within the Child Care Subsidy (CCS) program.

The management and oversight of compliance activities plays an important role in ensuring the proper use of CCS and the achievement of program outcomes. In the 2023–24 financial year, the department’s integrity activities resulted in the highest accuracy rates in provider claims for CCS on record, exceeding the program target.

These are substantial achievements, testament to the department’s commitment to strong regulation of CCS approved providers and its obligations under the Resource Management Guide-128.

The department is progressing a large work program to strengthen and further mature the delivery of its CCS compliance activities under the CCS Financial Integrity Strategy 2023–27. The department agrees with the seven recommendations and will address these as part of its ongoing commitment to strengthen the management and oversight of CCS compliance activities.

Services Australia

Services Australia (the Agency) welcomes the ANAO report on Management and Oversight of Compliance Activities within the Child Care Subsidy (CCS) Program. The Agency notes the report findings, including that management and oversight of compliance activities within the CCS Program are partly effective.

The Agency’s focus is on efficiently and effectively delivering payments and services to the Australian community, and compliance and program integrity are important aspects of this work. The Agency’s strategies, performance measures, and governance arrangements are focussed on ensuring the right payment to the right person at the right time.

The Agency is committed to continually improving its internal and external governance arrangements, performance monitoring and reporting, compliance activities, and guidance and support to staff to ensure the integrity of the CCS Program.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

21. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Program design

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Child Care Subsidy (CCS) is administered by the Department of Education (Education) under the Family Assistance Law (FAL)1:

to improve access to quality early childhood education and care by providing assistance to meet the cost of early childhood education and care for families engaged in work, training, study or other recognised activity.2

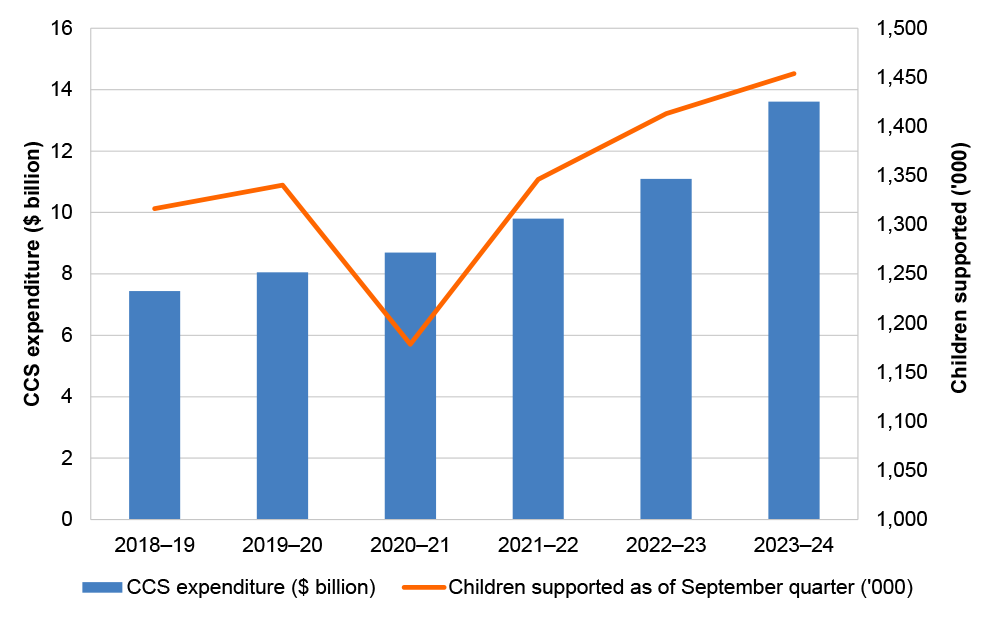

1.2 At a cost of $13.6 billion in 2023–24, CCS is one of the ‘fastest-growing major payments’ of the Australian Government, with forecast average annual growth of 5.5 per cent over 2024–25 to 2034–35.3 As of September 2024, CCS supported 1.45 million children to attend approved care (Figure 1.1). This equates to 32.6 per cent of all 0 to 13 year old’s in Australia.4

1.3 Education has policy responsibility for the CCS, including the CCS special appropriation. Services Australia is accountable for delivering payment and ICT services on behalf of Education, and for prioritising the service delivery within its budget appropriation.5

Figure 1.1: CCS expenditurea and childrenb supportedc

Note a: Expenditure does not precisely correspond to the number of children supported in each financial year, due to the reconciliation process undertaken after the end of each financial year.

Note b: The lower number of children in 2020–21 is because of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially service closures.

Note c: Figures include Additional CCS (ACCS), which provides support for: child wellbeing; grandparent care; temporary financial hardship; and transitioning to work.

Source: ANAO analysis based on the Education’s quarterly CCS data reports and annual reports.

1.4 Families apply to Services Australia to receive CCS. Entitlement to CCS depends on family income thresholds (Table 1.1) and activity requirements (Table 1.2). Families with more than one child aged 5 or under in care may get a higher subsidy for their second child and younger children.

Table 1.1: Standard CCS subsidy rates, 2024–25

|

Family income |

CCS subsidy rate for first child aged 13 or under |

Rate for second and younger children aged 5 or under |

|

$0 to $83,280 |

90% |

95% |

|

More than $83,280 to $141,321 |

Decreasing from 90% The percentage decreases by 1% for every $5,000 of income a family earns above $83,280. |

|

|

More than $141,321 to below $186,321 |

Decreasing from 95% The percentage decreases by 1% for every $3,000 of income a family earns. |

|

|

$186,321 to below $265,611 |

80% |

|

|

$265,611 to below $355,611 |

Decreasing from 80% The percentage decreases by 1% for every $3,000 of income a family earns. |

|

|

$355,611 to below $365,611 |

50% |

|

|

$365,611 to below $533,280 |

Higher CCS rates no longer apply, all children in the family will receive the standard CCS rate. |

|

|

$533,280 or more |

0% |

0% |

Source: ANAO based on the Education documents.

Table 1.2: CCS activitya requirementsb, 2024–25

|

Hours of activity each fortnight |

Hours of subsidised care, per child, each fortnight |

|

Less than 8 hours |

0 hours for family income above $83,280 24 hours for family income of $83,280 or below 36 hours — Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander child, regardless of family activity |

|

8 hours to 16 hours |

36 hours |

|

More than 16 hours to 48 hours |

72 hours |

|

More than 48 hours |

100 hours |

Note a: Recognised activities can include paid or unpaid work or leave, including parental leave and setting up a business, doing an approved course of education or training, actively looking for work, or other activities on a case-by-case basis. Families that are exempt from activity requirements (such as grandparents who are the principal carer of a grandchild) can access 100 hours of subsidised care per child per fortnight.

Note b: On 13 February 2025, legislation passed in Parliament to replace these activity requirements with guaranteed access to three days subsidised child care for CCS eligible children from 1 January 2026. See Parliament of Australia, Early Childhood Education and Care (Three Day Guarantee) Bill 2025, available from https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22legislation%2Fbillhome%2Fr7316%22 [accessed 17 February 2025].

Source: ANAO based on Education and Services Australia documents.

1.5 CCS is paid directly to approved providers by Services Australia and passed on to eligible families in the form of fee reductions. Families pay the difference between the provider’s fee and the subsidy amount (the ‘gap fee’) to the provider. Additional CCS (ACCS) may be paid to some families to provide additional support for: child wellbeing (if a child is vulnerable or at risk of harm, abuse or neglect); grandparent care; temporary financial hardship; and transitioning to work.

1.6 Throughout each year, a family’s CCS subsidy rate is based on estimated income. They must then confirm their annual income at the end of each financial year, generally by lodging a tax return with the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).6 If there is a difference between the person’s actual and estimated income, Services Australia repays the family for any underpayment, or recovers any overpayment as a debt. (See paragraphs 3.24 and 3.25).

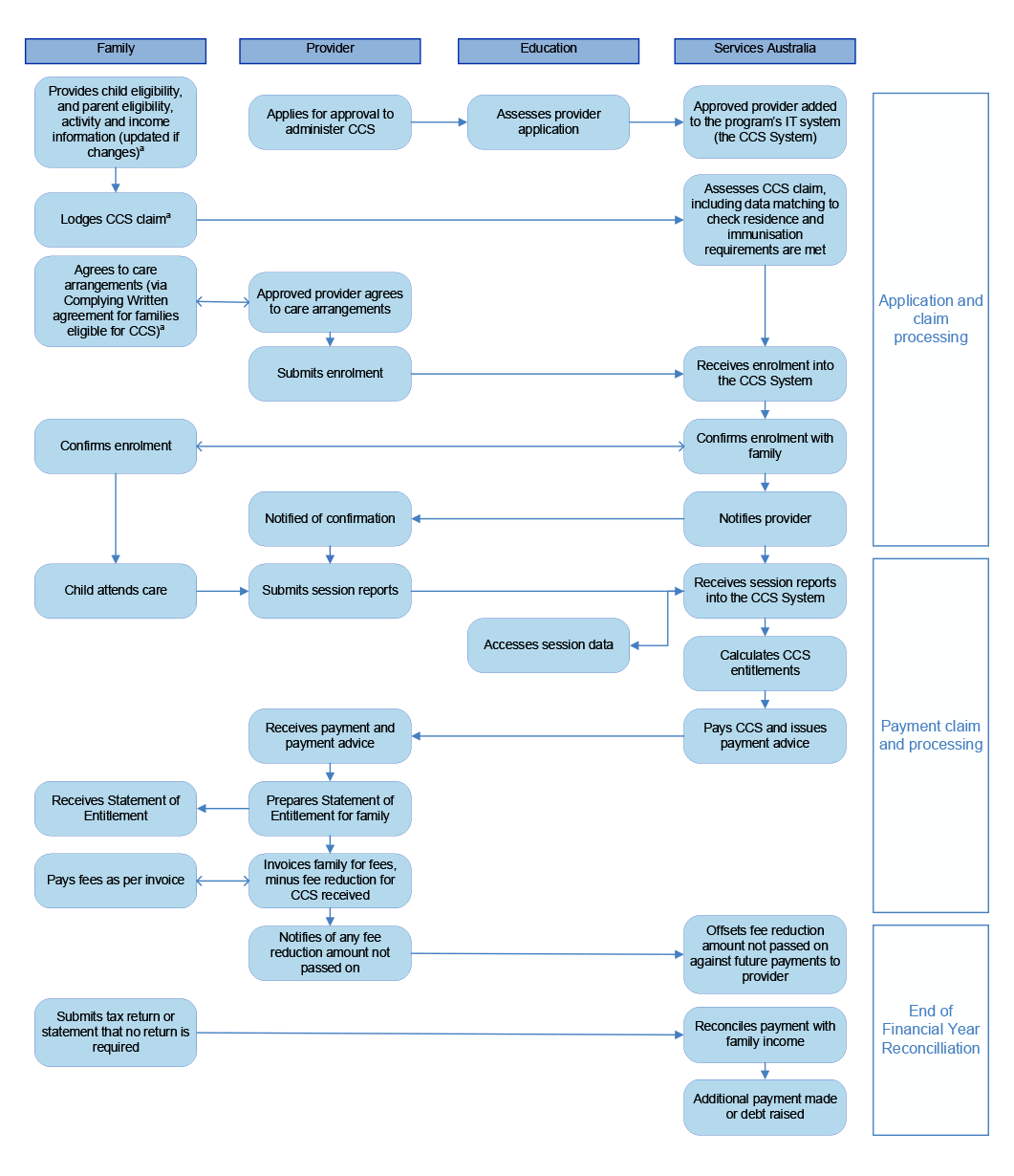

1.7 Education is responsible for approving providers and services to receive CCS payments on behalf of eligible families. Each provider must operate at least one service which provides care.7 In order to gain and maintain approval, providers and services must meet conditions set out in the FAL. The provider is the person or business entity responsible for operating the child care service (or services).8 Under the FAL, the provider is the legal entity that receives CCS payments, passes on payments in the form of fee reductions, and incurs a debt to the Commonwealth where CCS is paid incorrectly and the debt was caused by provider actions.9 The approval and payment process is summarised in Appendix 3 (controls to ensure the integrity of access to the CCS are discussed in Chapter 3).

1.8 Under the Education and Care Services National Law Act 2010 (Vic) (the National Law), state and territory regulatory authorities (SRAs) are responsible for assessing and approving early childhood education and care services and providers to provide care.10 SRAs assess applications against educational quality, child health and safety, physical environment, staffing, relationships with children, families and communities, and governance and leadership requirements under the National Quality Framework, which is administered by the Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority (ACECQA).11 The interface between state and Australian Government regulatory arrangements is discussed at paragraphs 2.28 and 2.30.

1.9 There are four types of care that can be approved for CCS and ACCS (Table 1.3). Of these, most subsidised care is provided by Centre Based Day Care, which received 85.3 per cent of CCS and ACCS funding in the September 2024 quarter.

Table 1.3: Services and childrena supported by CCS and ACCS for the September 2024 quarter

|

Type of care |

Description |

Approved services |

Children |

Subsidyb ($‘000) for September 2024 quarter |

|

Centre Based Day Care |

Provided in licenced or registered centres and includes child care such as long day care and occasional care |

9,472 |

845,980 |

3,334,937 |

|

Family Day Care |

Services provided in the educator’s home or an agreed venue to small groups of children |

357 |

71,340 |

195,058 |

|

Outside School Hours Care |

Provided to children generally of primary school age outside normal school hours (before and after school and can also be during school holidays or pupil free days) |

5,077 |

566,600 |

368,777 |

|

In Home Care |

Provided by an educator in the child’s home and restricted to families who cannot access other forms of early childhood education |

31 |

1,640 |

9,033 |

|

Total September 2024 quarterc

|

14,937 |

1,453,780 |

3,907,805 |

|

Note a: The ratio of children to educators, or children to care locations, cannot be inferred from this table. Each service may engage many educators across a large geographical region. See Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority, Educator to child ratios, ACECQ, available from https://www.acecqa.gov.au/nqf/educator-to-child-ratios [accessed 17 February 2025].

Note b: Amounts include both CCS and ACCS payments.

Note c: As children may use more than one service type, and due to rounding, the sum of the component parts may not equal the total.

Source: ANAO based on Education information.

Non-compliance in the CCS

1.10 Between 2018–19 and 2023–24, identified non-compliance accounted for an estimated $2.7 billion of total CCS expenditure of $58.7 billion (Table 1.4).12 Over this period, Education identified $13.0 million lost to CCS fraud, and recovered $116,707 of this from seven cases.

Table 1.4: Estimated total costa of CCS non-compliance, 2018–19 to 2023–24

|

|

Per cent of CCS payments |

Cost ($ million)b |

|

2018–19 |

4.1 |

305.3 |

|

2019–20 |

3.9 |

315.2 |

|

2020–21 |

5.2 |

455.7 |

|

2021–22 |

7.0 |

684.2 |

|

2022–23 |

3.8 |

420.2 |

|

2023–24 |

3.6 |

484.1 |

|

Total |

|

2,664.9 |

Note a: The rate of inaccurate payment is based on the Random Sample Parent Check (RSPC), which collects information from families about their children’s attendance at approved child care services. A comparison between the information provided by the families and the attendance information reported by services is used to measure payment accuracy. A payment is inaccurate if the information provided by the parent does not match that provided by the service. On 28 August 2024, Education advised the ANAO that RSPC data is the best available measure of all fraud and non-compliance within the CCS.

Note b: Values may not sum to total due to rounding.

Source: ANAO based on Education documents.

1.11 As of 2024–25, Education and Services Australia compliance activities are jointly funded via three budget measures summarised in Table 1.5.13 These measures contribute to funding staff in both entities, as summarised in Table 1.6. Appendix 4 provides more details about these measures and other key program changes.

Table 1.5: Funding for departmental investment in activities to address non-compliance in the CCS, 2022–23 to 2024–25

|

Budget measures |

|

2022–23 $’000 |

2023–24 $’000 |

2024–25 $’000 |

|

Child Care Subsidy Reform Integrity Packagea |

Education |

5,011 |

12,745 |

11,379 |

|

Services Australia |

– |

– |

– |

|

|

Child Care Subsidy Reform — additional integrityb |

Education |

– |

4,287 |

2,988 |

|

Services Australia |

– |

1,261 |

1,316 |

|

|

Child Care Subsidy Reform — further measures for strong and sustainable foundationsc |

Education |

– |

– |

52,365 |

|

Services Australia |

– |

– |

5,582 |

|

Note a: 2022–23 (October) Budget funded. This measure did not include any departmental funding for Services Australia.

Note b: 2023–24 Budget funded.

Note c: 2024–25 Budget funded.

Source: ANAO analysis of Australian Government budget papers.

Table 1.6: Staffinga to address non-compliance in the CCS, 2022–23 to 2024–25b

|

|

2022–23 |

2023–24 |

2024–25 |

|

Education |

94.1 |

127.5 |

182.0 |

|

Services Australia |

9.35 |

4.1 |

7.7 |

Note a: Staffing to address non-compliance activities in the CCS is comprised of budget measures funding and funding through departmental budget allocations. The Average Staffing Level (ASL) figures provided for 2022–23 and 2023–24 are actual ASL as at the end of each financial year, the 2024–25 ASL are the budgeted ASL for the financial year. Actuals for 2024–25 will not be known until the end of financial year.

Note b: This does not include staff undertaking functions that are not specifically identified and funded as compliance-related. This excludes the approximately 2,877 customer-facing staff in Services Australia (at 30 June 2024) trained to deliver CCS-related services (such staff usually also complete work on other programs).

Source: ANAO based on Education and Services Australia documents.

Previous audits and reviews

1.12 Auditor-General Report No. 10 2019–20 Design and Governance of the Child Care Package found that Education’s design and governance of the Child Care Package, which included the CCS, was largely effective, except that the focus on key policy objectives for the Package in key documentation had diminished over time, and ongoing oversight arrangements were not established in a timely manner.14

1.13 CCS was also considered as part of Auditor-General Report No. 28 2022–23 Debt Management and Recovery in Services Australia, which found that Services Australia’s debt management and recovery of social security and welfare debt on behalf of policy entities was partly effective. Services Australia did not have a coordinated approach for the debt management lifecycle including detecting potential overpayments, determining whether a potential overpayment is a legally recoverable debt, raising the debt and either waiving or recovering the debt.15

1.14 The need for improved compliance monitoring in the CCS was identified in ANAO Audit Report No. 13 2013–14 Audits of the Financial Statements of Australian Government Entities for the Period Ended 30 June 2013.16 In response, the Random Sample Parent Check (RSPC), which provides the basis for current measurements of non-compliance (paragraph 1.10) was introduced in 2014–15.17

1.15 Since 2021–22, performance statements audit has considered the effectiveness of the RSPC in measuring payment accuracy.18

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.16 The CCS was estimated to be one of the top 20 expense programs in 2024–25.19 Australian Government spending on CCS was $13.6 billion in 2023–24, of which an estimated 3.6 per cent ($484.1 million) was lost to incorrect payments, including fraud and non-compliance. Fraud and non-compliance reduces available funds for public goods and services.

1.17 This audit was conducted to provide assurance to the Parliament over the effectiveness of the management and oversight of compliance activities within the Child Care Subsidy program. This audit was identified as a priority by the Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit in the context of the ANAO’s 2023–24 Annual Audit Work Program.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.18 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the management and oversight of compliance activities within the Child Care Subsidy program.

1.19 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level audit criteria were adopted:

- Have effective governance arrangements been established?

- Is the approach to compliance activities effective?

Audit methodology

1.20 To assess the audit objective and criteria, the audit methodology included:

- examination and analysis of Education and Services Australia records;

- meetings with relevant Education and Services Australia staff; and

- extraction and analysis of compliance data from Education and Services Australia systems.

1.21 The audit was open to contributions from the public between 11 July and 15 December 2024. The ANAO received and considered one submission from a member of the public.

1.22 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $725,100.

1.23 The team members for this audit were Hazel Ferguson, Klein Anderson, Shannon Clark, Margaret Dunlop, Amanda Elliot, Kayla Hurley, Kristian Marchiori, Dale Todd, and David Tellis.

1.24 The ANAO has co-operative evidence gathering arrangements in operation with entities. On 4 July 2024 Services Australia advised the ANAO that it was unable to voluntarily provide certain information requested by the ANAO due to legislative restrictions on the disclosure of requested information. On 25 July 2024, the audit team issued Services Australia with a notice to provide information and produce documents pursuant to section 33 of the Auditor-General Act 1997 to enable it to provide the requested information taking account of legislative requirements. Services Australia provided the information requested within the specified time, following receipt of the notice.

2. Governance arrangements

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether effective governance arrangements have been established to oversee compliance activities within the Child Care Subsidy (CCS) program.

Conclusion

The Department of Education (Education) has established partly effective arrangements to oversee CCS compliance activities. Committees accountable to a Senior Executive Service (SES) Band 2 within Education oversee its Child Care Subsidy Financial Integrity Strategy 2023–2027 (Integrity Strategy), which sets out its approach to risk based and data driven regulation of CCS providers and services, to be implemented from 2023 to 2027. To successfully complete its implementation of the Integrity Strategy, Education will need to improve its Child Care Intelligence System (CCIS) data quality and implement evaluation arrangements across the full suite of its compliance interventions.

Bilateral arrangements between Education and Services Australia are set out in a Statement of Intent and Program Delivery Services Schedule for Child Care Subsidy Program, which detail the objectives, governance, risk and issue management, roles and responsibilities and assurance obligations for CCS services. These arrangements do not provide Education with sufficient oversight of CCS compliance activities within Services Australia. Education has established a CCS Fraud and Corruption Risk Assessment (FCRA), but this is not supported by engagement with Services Australia over shared risks. Services Australia has not established a FCRA that includes CCS.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at developing and implementing arrangements to ensure Education has sufficient oversight of Services Australia’s work as it relates to CCS compliance, and can directly measure the effectiveness of compliance activities.

2.1 Effective oversight is critical to proper use and management of public resources.20 To ensure oversight is effective where service delivery is split from policy responsibility, roles and responsibilities must be clearly defined, risks understood and addressed, and reporting frameworks in place to enable the entity with policy responsibility to have oversight of the services delivered by the other entity.21

2.2 Where entities are performing regulatory functions, their governance arrangements should be as set out in the Department of Finance Resource Management Guide 128, Regulator Performance (RMG 128), including the adoption of a risk based and data driven approach to operational policy development, administration, compliance and enforcement activities.22

Have effective arrangements been established to oversee compliance activities?

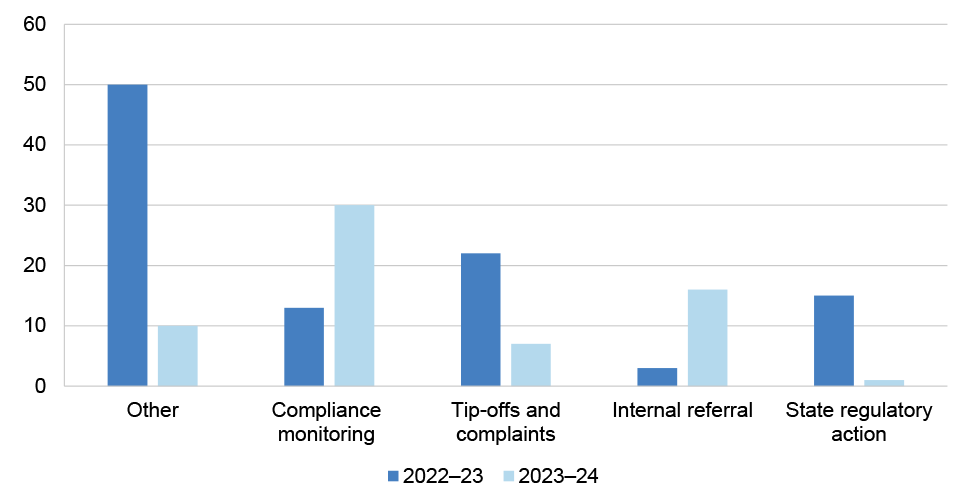

Education oversees CCS compliance activities via a Financial Integrity Governance Board (FIGB) and Financial Integrity Operational Committee (FIOC), that are accountable to the responsible Senior Executive Service (SES) Band 2. Education does not have visibility of compliance activities or risk management in Services Australia.

Bilateral arrangements between the Department of Education and Services Australia are set out in a Statement of Intent between the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Services Australia and the Secretary of the Department of Education (Education Secretary). Under the Statement of Intent, the Program Delivery Services Schedule for Child Care Subsidy Program details the objectives, governance, risk and issue management, roles and responsibilities and assurance obligations for CCS services. These do not provide sufficient oversight of CCS compliance activities.

Roles and responsibilities

2.3 Education has policy responsibility for administering the CCS, and Services Australia delivers CCS payments and IT systems on behalf of Education.

2.4 The Education Secretary, as the accountable authority for Education, is responsible for administering the CCS, including the CCS special appropriation, under the Family Assistance Law (FAL).23 The Education Secretary delegates certain powers under the FAL to the CEO of Services Australia, to allow Services Australia to determine individuals’ entitlement to be paid CCS, make relevant payments, recover overpayments, and undertake internal reviews of decisions.

2.5 Each entity’s responsibilities are affirmed in a Statement of Intent between the CEO of Services Australia and the Secretary of Education, and subordinate Program Delivery Services Schedule for Child Care Subsidy Program (the Services Schedule) (Appendix 5).

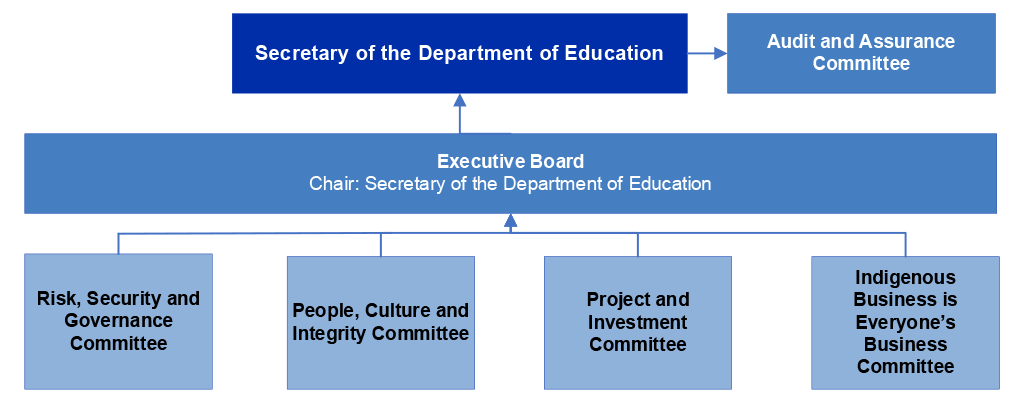

2.6 As the accountable authority, the Education Secretary is responsible for establishing governance arrangements to promote the proper use and management of public resources, and an appropriate system of risk oversight and management, as well as encouraging officials to cooperate with others to achieve common objectives, where practicable.24 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requires that an Accountable Authority ensure the entity has an audit committee.25 The Department of Education Governance Framework provides for an independent Audit and Assurance Committee (AAC), and four strategic governance committees which report to the Executive Board, Education’s key decision-making body (Figure 2.1).26

2.7 Education’s AAC was provided with information about CCS compliance work in 2022–23 and 2023–24. CCS compliance matters were discussed twice during this period by Education’s key governance committees. The Project and Investment Committee considered:

- Approving change to the schedule, budget and scope for a project related to the Civil Penalties Management System, which is used to send infringement notices, and conduct electronic funds transfer (EFT) provider audits and campaigns.27

- Consideration of a proposed budget for the Child Care Subsidy Digital Data Exchange project, which aims to automate early childhood education and care data extraction from Services Australia, and agreement that work would be undertaken to reduce the budget before it could be considered again.

Figure 2.1: Department of Education, key governance committees, 2022–23 and 2023–24a

Note a: In November 2024, Education’s governance arrangements were updated to remove the Risk, Security and Governance Committee, and rename the Audit and Assurance Committee the Audit and Risk Committee.

Source: ANAO based on Education documents.

2.8 Education’s oversight of its internal CCS compliance activities is generally provided via CCS specific committees, which do not report directly to Education’s key governance committees as set out in Figure 2.1. Instead, they are accountable to, and must have decisions ratified by, the accountable SES Band 2 or SES Band 1 officer. In 2022–23 and 2023–24, a total of 20 CCS compliance related decisions were escalated above the SES Band 2 to the Deputy Secretary or Secretary. These predominantly related to legal or funding approvals, or engagement with Services Australia or other entities. The committees do not directly report to the Deputy Secretary, Early Childhood and Youth, or Education Secretary.

Table 2.1: Department of Education oversight of CCS compliance functions

|

Body |

Established |

Purpose |

Membership level |

ANAO assessment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Is oversight provided in line with the body’s purpose? |

Are conflicts of interest dealt with effectively? |

|

Financial Integrity Governance Board (FIGB) |

June 2023 |

As the highest governance body within Education that has specific oversight of CCS integrity, the FIGB provides strategic oversight and direction to activities undertaken by Education teams.a |

SES Band 2 (Chair) and SES Band 1 levels |

✔ |

✘ |

|

Financial Integrity Operations Committee (FIOC)b |

May 2024 |

Under the strategic direction of the FIGB, the FIOC supports a coordinated response to CCS integrity risks by Education’s operational teams.a |

SES Band 1 (Chair) and EL2 levels |

✔ |

✔ |

Key: ✔ Yes ✘ No.

Note a: No oversight or coordination of Services Australia activities is provided by these bodies.

Note b: The FIOC was preceded by the Compliance Fraud Management Team (CFMT), which performed similar functions. The activities of the CFMT are not analysed in the table.

Source: ANAO based on Education documents.

2.9 In 2022–23 and 2023–24, the FIGB and FIOC met every six weeks, and operated in line with their respective stated purposes. For example:

- FIGB approved the Financial Integrity Strategy 2023–2027; and

- FIOC received operational updates, including teams’ caseloads, IT system updates and hot topics, and approved cases for referral.

2.10 Two deficiencies in these arrangements were identified:

- The FIGB had not established arrangements for members to declare conflicts of interest. The Australian Public Service Commission identifies regulators as having a ‘heightened risk’ of conflict of interest.28 While CCS staff must adhere to Education’s enterprise Conflict of Interest Policy, Education has not established specific guidance for its staff to manage conflicts of interest issues particular to regulators, such as issuing or reviewing fines or penalties. In accordance with Education’s Conflict of Interest Policy, staff attending FIGB meetings are required to declare actual and/or apparent conflicts (the SES requirement is to do so annually), but are not required to make a declaration at the opening of each meeting. Staff attending FIOC meetings are asked to declare conflicts at the opening of each meeting.

- Oversight arrangements did not cover the entire program. Despite having oversight of compliance activities administered internally, during 2022–23 and 2023–24, Education’s FIGB and FIOC did not have oversight of Services Australia’s compliance-related work, or the impact of this work on CCS compliance. The ANAO identified some examples of FIGB and FIOC members attending bilateral meetings with Services Australia, but these were meetings provided by the Statement of Intent, which focus on service standards rather than compliance activities (Table 2.2). During the audit, Education revised its governance arrangements to include Services Australia SES Band 2 and SES Band 1 membership in a new Joint CCS Program Board.

Opportunity for improvement

2.11 The Department of Education could consider developing specific guidance for CCS staff to aid in the management of conflicts of interest that may arise in the performance of their duties as a regulator.

2.12 Within Services Australia, the Families and Child Care Branch provides oversight of the entity’s work on CCS through its line management and committee structure. Relevant internal Services Australia meetings are documented via agendas only. As a consequence, there is no evidence these arrangements are used to oversee CCS compliance activities, except for the Services Australia Audit and Risk Committee, which was updated about major CCS fraud investigations that the entity engaged in, in 2022–23 and 2023–24. Services Australia provides regular reporting to Education under the Services Schedule but this does not include key compliance risks and controls (paragraph 2.20).

Table 2.2: Implementation of bilateral CCS governance arrangementsa by Education and Services Australia

|

|

Bilateral Management Committee |

Operational Committee |

|

Membership level as per the Statement of Intent |

Deputy Secretary/Deputy CEO |

SES Band 2 or delegate |

|

Purpose as per the Statement of Intent |

Fosters and supports a culture of alliance between policy objectives and service delivery across programs, fulfills ministerial objectives, and manages organisational relationship health and culture, and reputational and organisational risks |

Facilitates discussion, assessment, review and if necessary, problem resolution on matters relating to the Services Schedule |

|

Operating arrangements as per the Statement of Intent |

Meets quarterly; peak governance body for the relationship |

Required to meet quarterly; reports and escalates any unresolved issues or disputes to relevant deputy heads for consideration |

|

2022–23 and 2023–24 operating arrangements |

The Bilateral Management Committee has not met since 2022. Instead, regular Deputy Secretary/Deputy CEO meetings take place, but are not supported by formal agendas, minutes, or papers — records consist of notes each entity prepares for its senior executive. |

Operating as per Statement of Intent, except with SES Band 1 Chair and EL2 attendance |

|

2022–23 and 2023–24 meeting frequency |

No agreed meeting frequency. Meetings occurred twice in 2022–23, and seven times in 2023–24 |

Meeting more than required, at eight times per year across the relevant period |

|

CCS compliance matters dealt with 2022–23 and 2023–24 |

Deputy Secretary/Deputy CEO meetings focus on maintaining service standards and remediating service issues under the Services Schedule, with issues for discussion including:

|

|

Note a: Bilateral governance arrangements are taken from the Statement of Intent signed in July 2024, and Services Schedule, signed in March 2022. The previous Statement of Intent, signed in April 2021, also included the Bilateral Management Committee and supporting Operational Committee.

Source: ANAO based on Education and Services Australia documents.

Risk management

2.13 The Statement of Intent provides for the establishment of shared risk management arrangements. It states:

Managing shared risk is a crucial element of effective policy and program delivery. Entities will implement arrangements and jointly manage shared risk in accordance with the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy.

Entities agree to discuss the requirements for undertaking risk assessments and to cooperate in conducting any assessments required.

Entities will inform each other of risks relating to the performance of the services that come to its attention.

Specific risk management arrangements, including the requirement for any risk registers, are to be set out in the individual bilateral arrangements.

2.14 The Services Schedule identifies entities’ respective risk management responsibilities.

- Education is responsible for controlling risks to CCS payment accuracy in relation to:

- child care service providers;

- other third party or combined child care service providers; and

- individual non-compliant behaviours, such as where individuals and service provider collude in non-compliant behaviours.

- Services Australia is responsible for controlling risks to payment accuracy that are solely the result of CCS customer behaviours, changed circumstances, and system issues.

2.15 These arrangements mean risks involving individuals failing to accurately report their income or activity levels, or providing inaccurate information about their eligibility for CCS, are managed by Services Australia. Education is responsible for managing any risk that involves the provider or service, including where an individual colludes with a provider to fraudulently claim more CCS than they are entitled to. As CCS payments are made to the provider, the bulk of the non-compliance risk is managed by Education.

2.16 The risk management section of the Services Schedule does not address risks associated with legislation and policy, or IT system effectiveness, although responsibly for these is with Education and Services Australia respectively (Appendix 5).

2.17 In respect to shared risks, the Services Schedule specifies entities will:

cooperate in communicating and managing any identified risks and to discuss in good faith the requirements (including key resources, activities, deliverables and timeframes) for the conduct of risk assessments, privacy impact assessments, fraud assessments, business continuity assessments and other assessments.

…

The Operational Committee will be responsible for the management of shared risks.

2.18 The Operational Committee does not consider shared compliance risks. Between August 2023 and June 2024, Education attempted to address this deficiency. It shared information relevant to CCS fraud risks, and sought information from Services Australia on the same. In response, Services Australia provided a copy of its risk management plan, and a redacted risk control pressure test report.29

2.19 Separately from the Operational Committee, on 9 September 2024, Education and Services Australia held the first meeting to discuss shared risk management arrangements. Meetings to discuss shared risks continued in 2025.

Reporting

2.20 Services Australia’s reporting to Education is compliant with its obligations under the Services Schedule. It comprises:

- an annual assurance statement, which aligns with strategic principles set out in the Statement of Intent;

- monthly CCS and ACCS reports of claim processing, payments, reconciliations, and debts;

- a quarterly operational managers report, which summarises CCS and ACCS claim processing, reconciliation, debts, breaches, complaints, and internal and external reviews; and;

- daily and monthly financial reporting.

2.21 This reporting does not cover compliance risks or Services Australia’s management of these.

Recommendation no.1

2.22 The Department of Education and Services Australia review and revise arrangements giving effect to the Statement of Intent and subordinate documents to ensure sufficient oversight of shared regulatory activities is provided.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

2.23 The Department of Education (the department) acknowledges the ANAO’s report and its seven recommendations on the Management and oversight of compliance activities within the Child Care Subsidy (CCS) program.

2.24 The department has made substantial progress to improve and further mature its regulation of the CCS program during this performance audit, including creating a new branch to manage its regulatory functions and recruiting additional staff to support its compliance activities.

2.25 The department is committed to further improving its integrity approach. The key findings from this audit will be considered in further maturing its approach to addressing program risks, in line with its regulatory responsibilities.

Services Australia response: Agreed.

2.26 The Agency will continue to consult with the Department of Education on current bilateral arrangements and will negotiate revised arrangements to ensure there is sufficient oversight of shared regulatory activities.

Multi-agency and intergovernmental engagement

Multi-agency engagement

2.27 Education engages with other Australian Government entities via:

- the Fraud Fusion Taskforce, a forum for Australian Government entities, including the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC), Australian Federal Police (AFP), and Australian Taxation Office (ATO), to work together to share information and build skills detect and prevent fraud — Education proactively discloses intelligence via this forum;

- Task Force Reston, an ACIC operation which facilitates the sharing of criminal information within the Fraud Fusion Taskforce and supports the development of enhanced national responses to identify, prevent and disrupt fraud and related criminal activity within Australian Government payments and programs;

- the Government Payments Program, an ATO-led program to improve system integrity across Commonwealth programs through better use of ATO data;

- project-specific or investigation-specific engagement with other Australian Government entities, such as:

- search warrant assistance from the AFP (paragraphs 3.50 to 3.53);

- intelligence-related investigations assistance from the ACIC;

- work with the ATO to introduce Statement of Tax Record requirements to the CCS application process from 1 April 2025;

- work with the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre to identify people who have high unexplained wealth with connections to early childhood education and care;

- work with the ACIC, which is in the early stages of development, to increase information available about possible unsuitable and/or fraudulent actors applying for CCS approval; and

- work with the National Disability Insurance Scheme Quality and Safeguards Commission (NQSC) and the ACIC, which is in the early stages, to improve the identification of serious and organised crime and systemic fraud across programs.

Intergovernmental engagement

2.28 Education’s Child Care Subsidy Financial Integrity Strategy 2023–2027 (Integrity Strategy, paragraphs 2.32 to 2.33) states that Education’s regulation of providers and services under the FAL is separate from state and territory government regulatory authorities’ responsibilities for the safety and quality of early childhood education providers and services under the National Law.

2.29 The Integrity Strategy identifies ‘limited coordination with states and territories and other regulators’ as a challenge to be addressed. Work with state and territory governments on early childhood education system reform is progressed via the Education Ministers Meeting and subordinate Australian Education Senior Officials Committee and Early Childhood Policy Group. Inter-jurisdictional work with state and territory early childhood education and care regulatory authorities (SRAs) and the Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority (ACECQA) to improve regulation in early childhood education and care takes place via30:

- project-specific work on regulatory systems reform, such as ‘Joined Up Approvals’, to allow Education and SRAs to use a single application system (completed in June 2023, see paragraph 3.8), and the Joint Compliance Monitoring Program (under which joint investigations are conducted, see paragraphs 3.55 to 3.57);

- direct engagement with SRAs to share intelligence and perform complimentary regulatory action (for example attendance by the SRA at the execution of search warrants resulting from Education investigations);

- two non-decision-making regulatory communities of practice with SRAs and ACECQA:

- the Regulatory Practice Committee (RPC), a non-decision-making community of practice to share information and improve practice and ‘establish consistent, effective and efficient procedures for the operation of the NQF [National Quality Framework]’; and

- the Lead Investigator Network, a working group of the RPC, with a focus on investigative practice in monitoring and enforcing compliance with the Education and Care Services National Law and Regulations.

2.30 Limitations at the intersection between state and territory regulators and Education’s enforcement actions is discussed at paragraph 3.72.

Has a risk based and data driven approach to compliance been established?

Education’s Child Care Subsidy Financial Integrity Strategy 2023–2027 (Integrity Strategy) documents its approach to risk based and data driven regulation to be implemented from 2023 to 2027. To successfully complete its implementation of the Integrity Strategy, Education will need to improve its Child Care Intelligence System (CCIS) data quality.

Although Services Australia’s annual CCS risk management plans document its approach to managing risk in the program, including compliance risk, there is no documented approach (either in Education’s Integrity Strategy or via Services Australia’s own program documentation) that provides strategic direction or describes how risk and data inform decision-making regarding Services Australia’s CCS compliance activities.

Education has established a CCS Fraud and Corruption Risk Assessment (FCRA), although information about the purpose, implementation status, and timeframes of risk treatments is not included. Risk identification, analysis and evaluation within the FCRA is not supported by engagement with Services Australia over shared risks. Services Australia has not established a FCRA that includes CCS.

2.31 Principle 2 of RMG 128 states that regulators should adopt a ‘risk based approach to operational policy development, administration, compliance and enforcement activities, and [be] informed by data, evidence and intelligence.’ 31 This includes maintaining a compliance and enforcement strategy that articulates the regulator’s approach to risk and how this informs decision-making, publishing where appropriate.

Compliance approach

2.32 Education’s compliance approach is set out in the Integrity Strategy. The Integrity Strategy outlines a ‘whole-of-system’32 approach to address CCS ‘fraud and non-compliance’. Education published the Integrity Strategy on 26 August 2024, replacing the previous strategy, which had been in place since 2019. The Integrity Strategy is in the process of being implemented, with change actions ongoing to 2027 (paragraphs 2.38 to 2.44, 2.48, and 2.65 to 2.67).

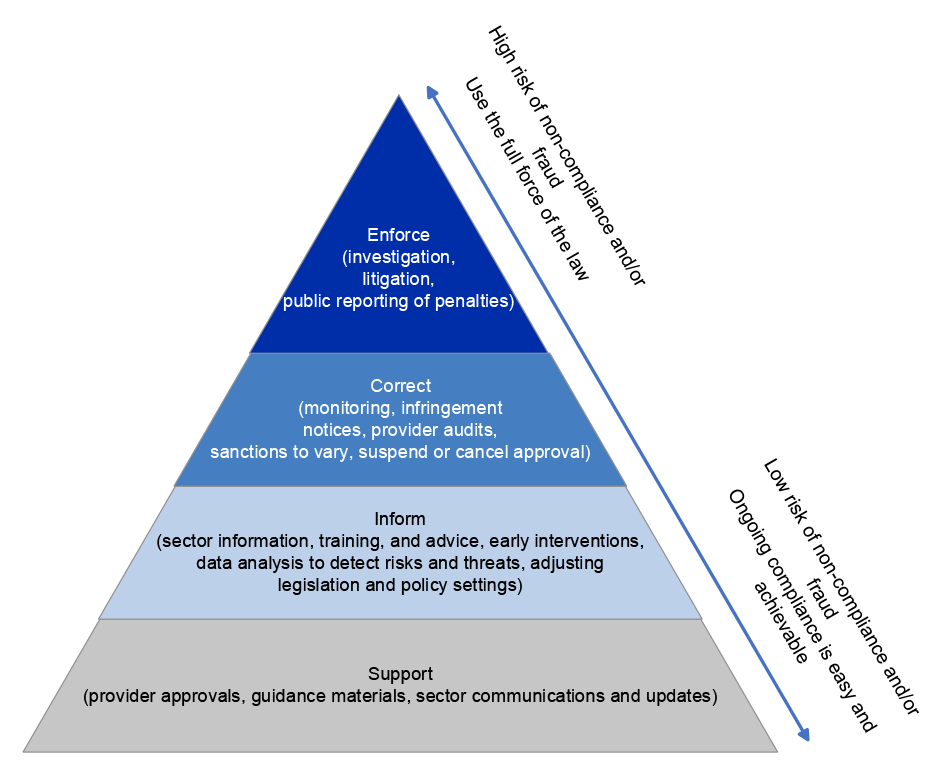

2.33 Education’s intended approach to addressing behaviours across the integrity continuum is depicted in a compliance pyramid (Figure 2.2), which includes enforcement, correction, information, and support activities, based on a provider’s risk profile and pattern of compliance behaviours, with most activity concentrated on preventative activity at the bottom of the pyramid. According to the pyramid, the entity’s pattern of compliance behaviour corresponds to Education’s likely intervention response. In the Integrity Strategy, for example, opportunistic non-compliance, where the entity ‘generally disregards compliance, has limited/poor compliance systems, governance and management is not compliance oriented or takes opportunities to exploit for personal gain’ would be addressed via corrective measures including EFT provider audits, infringement notices, and sanctions to limit, vary, suspend or cancel CCS access.

Figure 2.2: Department of Education CCS financial integrity compliance pyramid

Source: ANAO adapted from the Department of Education, Child Care Subsidy Financial Integrity Strategy 2023–2027.

2.34 Services Australia controls to mitigate CCS non-compliance risks are set out in a risk management plan, which is reviewed and updated annually (paragraphs 2.50 to 2.52). On 12 July 2024, Services Australia advised the ANAO that the CCS compliance strategy is ‘managed by our partner Agency, Department of Education’. Education’s Integrity Strategy does not account for any regulatory actions that may be taken by Services Australia, including those described in Service Australia’s risk management plan. As such, there is no document that provides strategic direction or describes how risk and data inform decision-making regarding Services Australia’s CCS compliance activities.

2.35 In 2024, both entities documented their regulatory approach in respective Statements of Intent, which respond to Ministerial Statements of Expectations, as detailed in guidance for entities that perform regulatory functions (including standalone regulators and those located within larger entities) in RMG 128.33

Data driven approaches to compliance

2.36 According to RMG 128, data driven regulation involves use of intelligence and data to inform a risk based approach to compliance and enforcement.

2.37 Education’s Integrity Detection Framework (the Framework) sets out its approach to managing, analysing, and sharing CCS compliance-related data to achieve the objectives of the Integrity Strategy. Key data sets for CCS compliance functions identified in the Framework are:

- CCS data, which covers all sessions of care (that is, the period for which a family is charged a fee for care of their child) that take place at each approved service;

- CCIS data, which records all CCS compliance activities;

- data from the Australian Business Register (Australian Business Name information is used to identify persons with management and control at child care centres); and

- Department of Home Affairs data (the movement record database is used to identify if any children and educators were overseas at the time a session of care is claimed to have taken place).34

2.38 Beginning in 2022–23, Education’s approach to compliance and enforcement is informed by analysis of CCS data against financial integrity risk indicators. A risk rating (from low to high35) is allocated to each service against each indicator. An overall rating is attributed to the service based on aggregating the service’s score on all indicators.

2.39 Six indicators were used to guide compliance activities in 2023–24. These were developed based on consultation with internal and external stakeholders, to develop profiles of non-compliant providers. Validation was then undertaken to test the applicability of the profiles beyond individual staff experience. As of December 2024, nine additional indicators have been added, and work is underway to introduce further indicators.

2.40 CCIS information and other administrative data on regulatory activity is accessed by staff to understand the compliance history of certain providers or services. These data sources are used in intelligence analytics reports, risk indicators work, and intelligence assessments (paragraph 2.47). ANAO analysis identified limitations in CCIS data quality including incomplete record keeping and incorrect categorisation of investigations (paragraph 3.60).

2.41 Data from Services Australia reporting (paragraph 2.20) is used to:

- provide information across the whole program (using Education and Services Australia data) in the form of ‘dashboards’ provided to senior executives;

- track trends via the Quarterly Operational Managers Report, and raise issues with Services Australia where Education has relevant concerns; and

- monitor the financial position of the program, including debt recovery outcomes and doubtful debt (i.e. estimates of debt not likely to be repaid).

2.42 Services Australia reporting (paragraphs 2.20) is not integrated into Education’s compliance-related analytics (paragraph 2.37 to 2.39).

2.43 On 27 September 2024, Services Australia advised ANAO that it uses data in the development and monitoring of risk management plans. Data matching forms the basis of many key controls in Services Australia’s Child Care Subsidy Risk Management Plan 2024–25 — this includes monitoring payroll data for certain CCS recipients, immigration data (for both children and educators) and immunisation data (for children) to confirm payment eligibility.

2.44 Education’s Integrity Strategy identifies addressing a ‘mismatch of data holdings and systems’ and ‘limited measurement of performance against outcomes’ between 2023 and 2027. Under the Integrity Strategy, the (January 2024) Data Improvement Plan sets out an approach to improve how Education collects, modifies, analyses, and uses CCS compliance-related data. The Data Improvement Plan was informed by interviews, a data survey across stakeholders and subject matter experts, and benchmarking against other organisations. As of March 2025, work under the Data Improvement Plan has focused on developing and refining risk indicators (paragraph 2.39).

Risk based approaches to compliance

2.45 RMG 128 states that risk based regulation involves considering risks in decision-making, actively monitoring and planning for emerging risks, and focusing compliance and enforcement activity where risks and impact of harm are greatest.

2.46 Regulators are also required to adhere to other risk management requirements, which apply to all Commonwealth entities, including managing shared risks (paragraphs 2.13 to 2.18) and managing fraud and corruption risks under the Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework 2024.

Education

2.47 Education’s Integrity Strategy provides that enforcement, correction, information, and support activities should be taken based on a provider’s risk profile (paragraph 2.33), which is developed using session data (paragraphs 2.37 to 2.39).

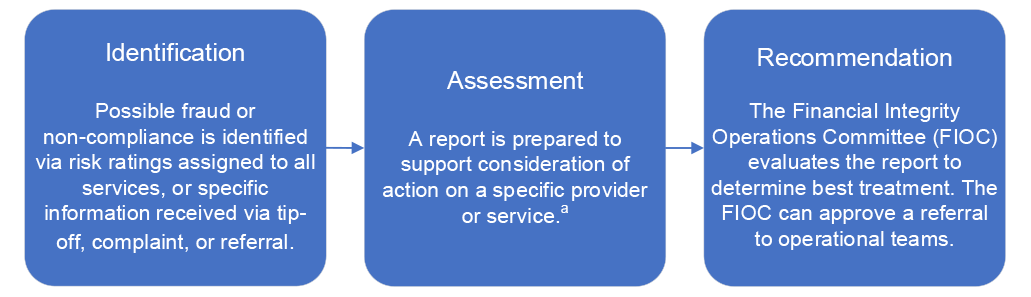

2.48 In 2023–24, Education implemented arrangements under the Integrity Strategy for using risk profiles in decision-making and focusing compliance and enforcement activity where risks and impact of harm are greatest (summarised in Figure 2.3).36 All decisions to take compliance activity made by FIOC (known as ‘referrals’ to the relevant team for further action) are supported by an assessment of provider or service risk profile. Bulk referrals are supported by a referral report with accompanying spreadsheets of services with risk rating information.37 Referrals based on information received via tip-off, complaint, or referral, may be supported by detailed intelligence assessments, which include risk ratings and compliance history information.

Figure 2.3: Education’s compliance risk identification, assessment and recommendation process

Note a: During 2022–23 and 2023–24, the report was an Intelligence Assessment Report (IAR). On 20 November 2024, Education advised the ANAO that its practice is to use ‘Referral Reports’ for bulk referrals, rather than Intelligence Assessment Reports. Referral reports provide a short overview of the matter being referred, risk indicators, compliance history, and the coordination team’s recommendation of whether, given the information provided, the matter should be accepted for investigation. The use of referral reports for bulk referrals is evident in FIOC papers starting in September 2024, although neither of the investigation teams’ policies refer to this process.

Source: ANAO analysis of Education documents.

2.49 Education has established a Fraud and Corruption Risk Assessment (FCRA). Two deficiencies in Education’s FCRA were identified:

- risk identification, analysis, and evaluation was not supported by engagement with Services Australia over shared risks; and

- risk treatment information was incomplete:

- information about the purpose, implementation status, and timeframes of risk treatments was not included.

- teams were identified as risk owners, contrary to the guidance provided in the template, which indicates risk owners should be ‘the SRO [Senior Responsible Officer] or other senior officer’ — a revised version of the FCRA was produced during the audit to address this issue.

Services Australia

2.50 Services Australia’s CCS risk management plan is updated annually. Child Care Subsidy Risk Management Plan 2024-25 risk 4 covers CCS compliance matters. This risk is owned by the National Manager (NM) Families and Child Care Branch. The risk management plan covers risk causes, consequences, and controls relevant to mitigating the risk of fraud and non-compliance in the CCS. The plan relies predominantly on prevention, especially system rules and controls (16 of 18 controls are at least partly preventative), and detection through data matching.

2.51 Services Australia’s risk management plan guidance for 2024–25 notes that reviews of plans should include ‘assessing emerging risks … for inclusion in the RMP [risk management plan] and updating risk decision statements and risk assessments if emerging risks are significant’. On 27 September 2024 Services Australia advised the ANAO that the data reported to Education is used in the continuous monitoring of and development of risk management plans (paragraph 2.42).

2.52 Services Australia has not established a FCRA for CCS, collaborated with Education in the development of its CCS FCRA, or included CCS in its entity-wide FCRA.

Is the compliance approach regularly reviewed, and where appropriate, updated?

Education monitors the effectiveness of the Integrity Strategy using payment accuracy data drawn from the Random Sample Parent Check (RSPC), and reporting against budget savings measures. As of March 2025, evaluations of compliance interventions have been planned but not yet implemented across the full suite of compliance interventions. Initial intervention evaluations and resulting adjustments for each team are due to be completed in 2025. As such, it is not possible to effectively measure the impact of compliance activities undertaken under the Integrity Strategy, or understand the relative contributions of different types of compliance activities.

Performance measurement and monitoring

2.53 Education measures the effectiveness of the Integrity Strategy against:

- the program’s overall payment accuracy rate target of over 90 per cent, which was set in 2018 based on a reduction from 95 per cent due to ‘changes to integrity resourcing and management systems’ and the replacement of existing programs with the CCS;

- an internal goal of 95 per cent payment accuracy — this was achieved in 2022–23 and 2023–24 (Table 1.4), but no basis for this has been documented; and

- a savings target of $448.3 million by the end of 2026–27, which reflects the combined savings agreed in CCS compliance-related October 2022 Budget and 2023–24 Budget measures.

Payment accuracy

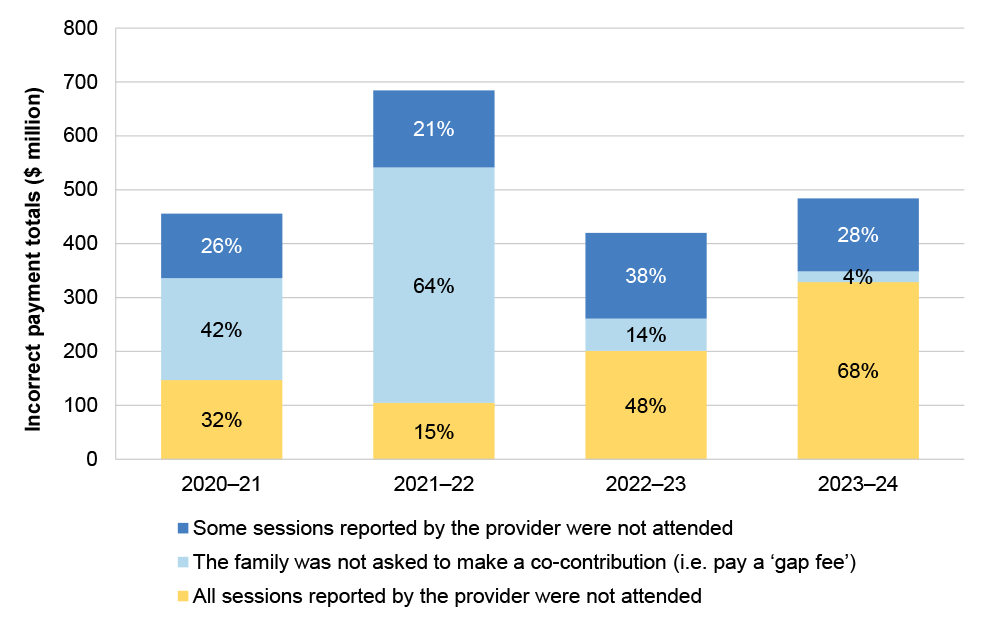

2.54 Payment accuracy is estimated, using the Random Sample Parent Check (RSPC).38 The RSPC compares attendance data from providers with survey responses from families about their children’s attendance. It measures three reasons for a payment being made incorrectly:

- all sessions reported by the provider were not attended;

- some sessions reported by the provider were not attended; and

- the family was not asked to make a co-contribution (i.e. pay a ‘gap fee’).

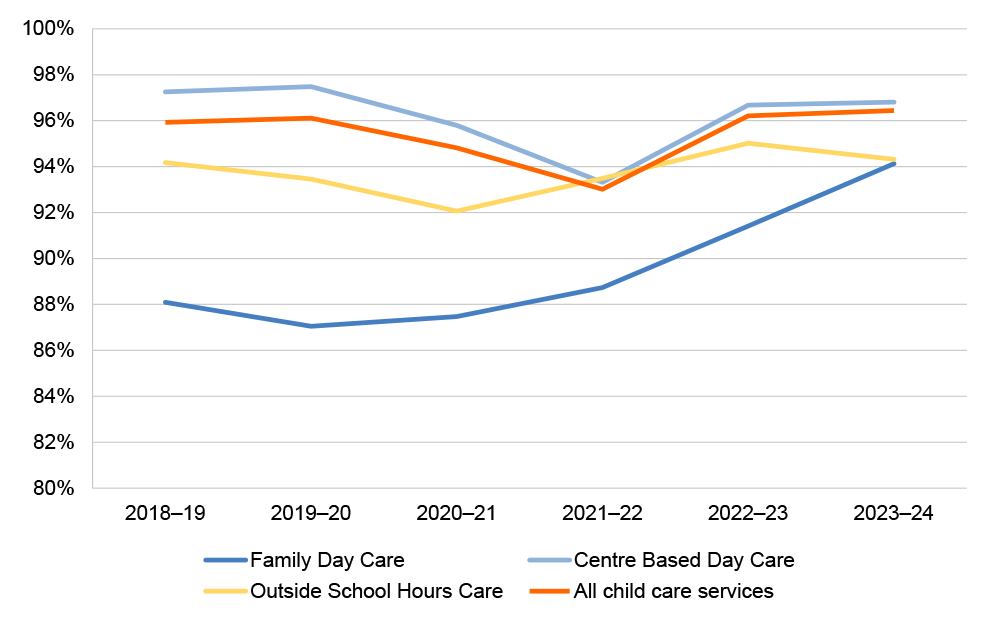

2.55 The contracted survey provider39, which has been engaged until 30 June 2026, reports quarterly and annually to Education on estimated payment accuracy rates by service type (Figure 2.4) and reasons for incorrectness (Figure 2.5). Education reports overall payment accuracy against the target of over 90 per cent in its annual report. (See Appendix 2 for additional reporting introduced during the course of this audit.)

Figure 2.4: CCS payment accuracy by service typea, 2018–19 to 2023–24

Note a: In Home Care service type is not captured by the RSPC.

Source: ANAO based on Education documents.

Figure 2.5: CCS, reasons for payment inaccuracy, 2020–21 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO based on Education documents.

Savings

2.56 The savings target of $448.3 million by the end of 2026–27 is based on the compliance-related October 2022 Budget and 2023–24 Budget process, which were costed based on activity in the following areas:

- the Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) audit program;

- fraud investigations;

- compliance operations with states and territories; and

- early intervention compliance campaigns.

2.57 The measure costings have been assured by the RSPC supplier. Education reports progress against the two budget measures via:

- senior executive briefing provided for Senate Estimates;

- budget commitment tracking reports provided to the Minister for Early Childhood Education since August 2024; and

- advice to government against budget measures, which provides progress against the savings target from 25 October 2022 to 15 January 2024, and shows savings targets being exceeded.

2.58 Education reporting on the budget measures that form the basis for the Integrity Strategy savings target shows estimated savings from 25 October 2022 to 30 June 2024 were $242.8 million against a target of $121.5 million. Total savings from all three integrity-related budget measures to December 2024 (Table 1.5) were $318.2 million against a target of $187.4 million.

Limitations

2.59 Under the Integrity Strategy, the effectiveness of teams’ execution of their work is measured according to Team Performance Frameworks. Although Education evaluates some of its compliance activities (namely communication campaigns and training, see paragraphs 3.14 and 3.16), only one intervention has been measured and progress reported against payment accuracy targets and program savings (case study 1). Regular evaluations of interventions, using RSPC data, is planned but as of March 2025 has not been implemented. Initial intervention evaluations and resulting adjustments for each team are due to be completed in 2025. As such, it is not possible to effectively measure the impact of compliance activities undertaken under the Integrity Strategy, or understand the relative contributions of different types of compliance activities. (See Appendix 2 for progress during the course of this audit.)

2.60 Education’s reporting does not draw a direct link between the savings attributed to budget measures, and improvements in payment accuracy as recorded by the RSPC, or the relative contributions of different activities to payment accuracy rates.

2.61 RSPC data is not used to direct compliance activity at a provider or service level. Service level non-compliance detection is discussed at paragraphs 2.37 to 2.46, and using RSPC data in enforcement is discussed at paragraphs 3.69 to 3.73. Education advised the ANAO on 1 August 2024 that using the RSPC to target individual cases for compliance action would undermine the integrity of RSPC itself, by potentially causing changes to the way people respond to the survey.

Recommendation no.2

2.62 The Department of Education strengthen its approach to implementing evaluation of the effectiveness of compliance interventions, to cover all interventions in the Child Care Subsidy Financial Integrity Strategy 2023–2027.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

2.63 See paragraphs 2.23 to 2.25.

Arrangements to review and update the Integrity Strategy

2.64 Education does not include strategy review arrangements in its Integrity Strategy. The current strategy was endorsed by the FIGB in August 2023, and published on 26 August 2024, replacing the previous strategy, which had been published in 2019. On 31 July 2024, Education advised the ANAO the development of the 2024 strategy was not informed by a review or evaluation of the previous strategy.

2.65 Under the Integrity Strategy, changes to compliance activities are set out in Integrity Response Plans (IRP), which describe the goals, scope, required resources, deliverables, measures of success, roles and responsibilities, and implementation schedules for actions across different operational teams in response to ‘high value’ integrity risks. 40 As of December 2024, one IRP has been developed, the Integrity Response Plan for Initial CCS Risk Indicators 2023–24. This IRP provided targets for compliance activities, including the number of EFT provider audits and investigations to be undertaken.