Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of International Travel Restrictions during COVID-19

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- This audit was conducted under phase two of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that focuses on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Australia’s COVID-19 international travel restrictions have affected individuals and businesses, including Australia’s international tourism, travel, aviation and education sectors.

Key facts

- Australia’s international travel restrictions have included the: inward and outward travel restrictions; cruise ship requirement; mandatory quarantine; international arrival caps; and India travel pause.

- Most of these travel restrictions were implemented from March 2020 and remained in place in October 2021.

What did we find?

- Management of Australia’s international travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic has been largely effective.

- While Australia did not have a plan to implement travel restrictions, subsequent decisions have largely been informed by robust planning and policy advice.

- Arrangements established to manage travel restrictions have been largely effective.

- Home Affairs’ management of inward and outward travel exemptions has been partially effective.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made six recommendations relating to: clearly communicating border clearance processes; planning for future travel restrictions; updating the response plan; obtaining data on quarantine; and better managing travel exemption refusal processes. Entities agreed to or supported all six recommendations.

458,310

Number of international arrivals to Australia from 1 April 2020 to 30 June 2021.

53,143

Number of inward exemptions approved by Home Affairs from 20 March 2020 to 30 June 2021.

814,310

Number of international departures from Australia from 1 April 2020 to 30 June 2021.

171,029

Number of outward exemptions approved by Home Affairs from 25 March 2020 to 30 June 2021.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Since its emergence in late 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a global pandemic that is impacting on human health and national economies. From January 2020 the Australian Government commenced the introduction of a range of policies and measures in response to the emergence of COVID-19 that included:

- travel restrictions, international border controls and quarantine arrangements;

- delivery of substantial economic stimulus, including financial support for affected individuals, businesses and communities; and

- support for essential services and procurement and deployment of critical medical supplies (including the national vaccine rollout).

2. After implementing initial country-specific travel restrictions in February and early-March 2020, Australian governments implemented a series of broad COVID-19 international travel restrictions from mid-March 2020 that remained in place in September 2021:

- restrictions on cruise ship arrivals to Australia (the cruise ship requirement);

- restrictions on foreign nationals entering Australia (the inward travel restrictions);

- restrictions on Australian citizens and permanent residents leaving Australia (the outward travel restrictions); and

- requirements for international arrivals to quarantine for 14 days at designated hotels or other facilities managed by state and territory governments (mandatory quarantine).

3. From April 2020 the Australian Government implemented two additional restrictions:

- caps on passenger arrival numbers at international airports from July 2020 to alleviate pressure on state hotel quarantine programs (international arrival caps); and

- restrictions on travel from India in May 2021 (the India travel pause).

4. The Department of Health has been the lead entity for managing the public health response to COVID-19. The Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs), which includes the Australian Border Force (ABF), has managed travel restrictions at the international border, including exemptions from the inward and outward travel restrictions. Other entities involved in managing Australia’s COVID-19 international travel restrictions have been: the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade; the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications (DITRDC); and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C).

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. The COVID-19 pandemic and the pace and scale of the Australian Government’s response impacts on the risk environment faced by the Australian public sector. This performance audit was conducted under phase two of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that focuses on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.1

6. Australia’s COVID-19 international travel restrictions have affected a large number of individuals and businesses, including Australia’s international tourism, travel, aviation and education sectors. Accordingly, there has been significant Parliamentary and public interest in the Australian Government’s management of the restrictions. The audit was conducted to provide independent assurance to Parliament that travel restrictions have been managed effectively.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the management of international travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Have Australia’s COVID-19 international travel restrictions been informed by robust planning and policy advice?

- Have effective arrangements been established to manage Australia’s COVID-19 international travel restrictions?

- Have inward and outward travel exemptions been managed effectively?

8. The audit focussed on policy advice to the Australian Government on international travel restrictions and the Australian Government’s management of the inward and outward travel restrictions and international arrival caps to 30 June 2021.

Conclusion

9. Management of Australia’s international travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic has been largely effective.

10. Australia did not have a plan to implement international travel restrictions and mass quarantine in response to a pandemic as health experts had concluded that such measures were not effective. Subsequent decisions on implementing COVID-19 international travel restrictions have largely been informed by robust planning and policy advice.

11. Arrangements established to manage Australia’s COVID-19 international travel restrictions have been largely effective. Adequate whole-of-government coordination and information sharing has occurred and strategies implemented to communicate travel restrictions have been appropriate. Arrangements established to manage the inward and outward travel restrictions and international arrival caps have largely been effective in achieving the Government’s policy intent.

12. Home Affairs’ management of inward and outward travel exemptions has been partially effective. Home Affairs has developed largely appropriate policies and procedures for managing inward and outward travel exemptions, with the quality of these improving over time. However, policies and procedures have not been consistently complied with.

Supporting findings

Planning and policy advice

13. Following a 2019 Health expert review, which concluded that the use of international travel restrictions and mass quarantine of arrivals to control a pandemic should not be attempted, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic Australia did not have any planning in place to support the implementation of such measures. (See paragraphs 2.4 to 2.26)

14. Expert advice on public health risks was largely provided to inform decisions on the initial design of Australia’s international travel restrictions, although early advice did not recommend implementing travel restrictions. Advice on legal risks was obtained for all travel restrictions. Home Affairs informed the ANAO it provided verbal advice to the Government from February 2020 on the legal risks of the inward travel restrictions, but could not demonstrate that it provided timely written advice. (See paragraphs 2.27 to 2.88)

15. Subsequent advice to the Australian Government on COVID-19 international travel restrictions has been largely robust and responsive to developments in the biosecurity risk environment. Health has conducted regular monitoring of the biosecurity risk environment. Extensions and adjustments to international travel restrictions were not always informed by expert advice on public health risks. (See paragraphs 2.89 to 2.119)

Management arrangements

16. Arrangements established to share information and coordinate between entities in managing international COVID-19 travel restrictions have been largely appropriate. While adequate coordination and information sharing has occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, role clarity and accountability would be enhanced through better documentation of coordination arrangements. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.27)

17. Appropriate strategies have been implemented to communicate travel restrictions. Entities have used existing communications channels to communicate COVID-19 travel restrictions to the public and relevant industry sectors, although the strategy of releasing public messages early led to implementation challenges. (See paragraphs 3.28 to 3.47)

18. The arrangements Home Affairs implemented to manage the inward and outward travel restrictions have been effective in achieving the Government’s policy intent of restricting international travel for specific cohorts. (See paragraphs 3.48 to 3.63)

19. PM&C and DITRDC have established largely effective arrangements to manage caps on international passenger arrivals. There is scope for better monitoring of quarantine capacity and use, and for increased use of agreed over-allocation processes in order to achieve full utilisation of quarantine capacity. (See paragraphs 3.64 to 3.88)

Management of travel exemptions

20. Appropriate policies and procedures have been established for travel exemption decision-making. Home Affairs has progressively enhanced its exemption case management arrangements, including developing an online exemption portal. While Home Affairs has established processes to obtain assurance over exemption decision-making, its analysis of and reporting on quality assurance results could be strengthened. (See paragraphs 4.4 to 4.29)

21. Decisions about inward travel exemptions have not consistently been managed in accordance with policies and procedures. There were also cases where inconsistent decisions were made even where there was conformance with policy. Insufficient feedback has been provided to unsuccessful applicants and mechanisms for seeking a review of an exemption decision should be improved. Since August 2020 Home Affairs’ processing of inward travel exemptions has been reasonably timely. (See paragraphs 4.30 to 4.66)

22. Decisions about outward travel exemptions have not consistently complied with policies and procedures, and there are indications that decision-making has not always been consistent even when in conformance with policy. The timeliness of outward travel exemptions has declined in 2021. (See paragraphs 4.67 to 4.86)

23. Visa processing has supported travel restrictions. Visa processing has continued during the COVID-19 pandemic and a number of temporary policy changes were made to support essential travel and existing visa holders. Efforts have been made to align decision-making and processing of applications in the travel exemption and visa programs. (See paragraphs 4.87 to 4.97)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.57

Department of Home Affairs update its current advice to industry on border clearance processes, and develop guidance for departmental officers for future advice, to ensure that it clearly outlines, where relevant and appropriate:

- legislative basis;

- responsible decision-maker; and

- potential consequences of not following the advice.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.120

Department of Health conduct a post-pandemic review to assess:

- when and how international travel restrictions and mass quarantine of arrivals should be applied for future pandemics, including roles and responsibilities; and

- the adequacy of the legal framework under which these measures operate.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.10

Department of Health ensure that the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus remains up to date and documents current governance and coordination arrangements, response measures and entity roles and responsibilities.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.72

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet work with states and territories to obtain robust data on quarantine capacity and use, including international passenger admissions to quarantine, and report the data publicly.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet response: Supported.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 4.41

Department of Home Affairs ensure, where exemption requests are refused, applicants receive specific feedback on the reasons for refusal.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 4.51

Department of Home Affairs ensure that its review mechanisms for travel exemption decisions:

- are communicated and readily accessible to applicants;

- facilitate adequate review of any issues raised; and

- provide clear and tailored communication to applicants about the outcome of the review.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

24. Entities’ summary responses to the report are provided below and their full responses are at Appendix 1. The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet did not provide a summary response.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (the department) welcomes the findings and recommendations of the audit, specifically the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO’s) conclusion that the management of Australia’s international travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic has been largely effective. DFAT continues to work closely with agencies on the Australian Government’s COVID-19 response. The department thanks the ANAO for the opportunity to comment.

Department of Health

The Department of Health (department) welcomes the findings in the report and accepts the recommendations directed to the department.

The COVID-19 pandemic is undoubtedly the most challenging and rapidly evolving global health crisis of our time. Many difficult decisions such as implementing travel restrictions, have been made to protect the health of all Australians – to minimise morbidity, mortality and the burden to the health system.

It was pleasing to note the ANAO considers the arrangements for and the management of Australia’s international travel restrictions have been largely effective. While it was noted that there was not a specific plan to guide the implementation of travel restrictions, it was gratifying for the ANAO to acknowledge that decisions made around travel restrictions have largely been informed by robust planning and expert policy advice that was responsive to developments in the biosecurity risk environment.

The effective cross agency collaboration and response partnerships with the states/territories and industry were reaffirmed by ANAO’s findings that there was adequate whole-of-government coordination and information sharing, and appropriate strategies were implemented to communicate travel restrictions, using existing communications channels. It was also noted that the arrangements established to manage inward and outward travel restrictions and international arrival caps were effective in achieving the Government’s policy intent.

Department of Home Affairs

The Department of Home Affairs welcomes this ANAO performance audit and acknowledges the valuable role it plays in providing independent insights into potential areas of further improvement.

Since the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, the Department played a key role in advising Government on border impacts and risks associated with proposed crisis management responses and giving practical effect to Government’s policy decisions in relation to Australia’s travel restrictions.

The travel exemption program aims at reducing the instance of COVID-19 crossing the border and entering Australia while maintaining a level of ongoing international travel arrangements despite the ongoing pandemic and consequent severe public health risk. The travel exemptions process is unprecedented, with unquantifiable predictions of volume. While the Department accepts that travel exemptions outcomes in a small number of cases may not have been consistent with policy guidance, this must be considered in the context of the large volume of rapid exemption decisions (over 900,000) that were made.

The Department welcomes the audit’s lead finding that the management of Australia’s international travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic has been largely effective. The Department also agrees with the audit’s three findings that identify areas where border management processes can be improved.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications

The Department acknowledges the ANAO’s conclusions and findings relevant to our operations, particularly the management of international passenger arrival caps. The Department notes there were no specific recommendations related to the Department arising out of the report.

With respect to the ANAO’s suggestion that there is scope for greater use of its ability to over-allocate capacity to maximise use of available quarantine, the Department does seek to over allocate to improve utilisation rates. However, in recent months some States have required the Department to maintain tight control over inbound passenger arrival caps without over allocations.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Policy/program design

Policy/program implementation

1. Background

1.1 Since its emergence in late 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a global pandemic that is impacting on human health and national economies. On 21 January 2020 the Australian Government declared COVID-19 as a listed human disease under the Biosecurity Act 2015 (Biosecurity Act).2 The World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 to be a ‘public health emergency of international concern’ on 30 January 2020.

1.2 From January 2020 the Australian Government commenced the introduction of a range of policies and measures in response to the emergence of COVID-19. On 18 March 2020, in response to the pandemic in Australia, the Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia declared that a human biosecurity emergency exists.3

1.3 The Australian Government’s health and economic response has included:

- travel restrictions, international border controls and quarantine arrangements;

- delivery of substantial economic stimulus, including financial support for affected individuals, businesses and communities; and

- support for essential services and procurement and deployment of critical medical supplies (including the national vaccine rollout).

1.4 With the release of the 2021–22 Budget on 11 May 2021, the Australian Government reported that it had committed $20 billion to COVID-19 health support measures and $291 billion to economic response measures.4

International travel restrictions during COVID-19

International travel restrictions introduced from February 2020 to June 2021

1.5 On 21 January 2020 the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) raised its travel advice for the city of Wuhan in China to ‘Level 2 – Exercise a high degree of caution’.5 Over following days travel advice levels for Wuhan, Hubei Province and mainland China were raised several times.

1.6 Based on advice from the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) within the Department of Health (Health) and the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC)6, on 1 February 2020 the Australian Government agreed to: implement a 14 day ban on foreign nationals entering Australia from China; and require Australian citizens, permanent residents and their immediate families returning from China to self-isolate for 14 days. These were Australia’s first international travel restrictions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.7 The Australian Government subsequently decided to extend the China travel restrictions (on 13 February 2020) and implement additional restrictions for Iran (on 29 February 2020), South Korea (on 5 March 2020) and Italy (on 11 March 2020). In addition, on 3 and 7 February 2020 the CMO, in his capacity as Director of Human Biosecurity, made three determinations under section 113 of the Biosecurity Act to declare ‘human health response zones’ to support the quarantine of Australians returning from China and the Diamond Princess cruise ship in Japan.7

1.8 From mid-March 2020, as the public health risks of the COVID-19 pandemic became more apparent, Australian governments replaced these initial country-specific travel restrictions with four broad COVID-19 international travel restrictions, which remained in place in September 2021.

- Cruise ship requirement — Following COVID-19 outbreaks on international cruises, the Australian Government decided on 15 March 2020 to introduce a requirement using subsection 15(3) of the Customs Act 1901 that international cruise ships not enter Australian ports. On 18 March 2020 the cruise ship requirement was brought under a human biosecurity emergency determination made by the Minister of Health under section 477 of the Biosecurity Act.8

- Inward travel restrictions — On 19 March 2020, due to around 80 per cent of COVID-19 cases in Australia having caught the virus overseas, the Prime Minister announced Australia was ‘closing its borders to all non-citizens and non-residents’ from 9pm on 20 March 2020.9

- Outward travel restrictions — To avoid ‘travellers returning to Australia with coronavirus and the risks of spreading coronavirus to other countries’, on 24 March 2020 the Prime Minister announced a ban on Australians travelling overseas.10 The outward travel restrictions were enacted by the Minister of Health the following day through a section 477 Biosecurity Act determination.11

- Mandatory quarantine — Australian governments agreed on 15 March 2020 that international travellers arriving in Australia be required to self-isolate for 14 days, and on 27 March 2020 that all international arrivals be required to quarantine for 14 days at designated hotels or other facilities.12 The latter announcement noted the quarantine arrangements would be ‘implemented under state and territory legislation’ and ‘enforced by state and territory governments, with the support of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and the Australian Border Force (ABF) where necessary’.13

1.9 For the inward and outward travel restrictions, the Australian Government established a range of automatic exemptions (outlined in Table 1.1). There were changes to exemption categories over time, including changes relating to the implementation of an Australia–New Zealand quarantine free travel zone (in place for one-way travel from New Zealand to Australia from October 2020 and two-way travel from April 2021, except when suspended due to COVID-19 outbreaks).

Table 1.1: Automatic exemptions from the inward and outward travel restrictions

|

Inward travel restrictions |

Outward travel restrictions |

|

|

Source: Home Affairs and ABF, ‘Inwards Travel Restrictions Operation Directive’ v.3 and ‘Outward Travel Restrictions Operation Directive’ v.8, no date, available from https://covid19.homeaffairs.gov.au/travel-restrictions [accessed 25 June 2021].

1.10 In addition to automatic exemptions, the Australian Government agreed to allow the ABF Commissioner and delegated officers within the Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs), including the ABF, to grant discretionary exemptions from the inward and outward travel restrictions (outlined in Table 1.2). As at 30 June 2021, 171,029 outward discretionary exemptions and 53,143 inward discretionary exemptions had been approved.

Table 1.2: Discretionary exemptions from the inward and outward travel restrictions

|

Inward travel restrictions |

Outward travel restrictions |

|

|

Source: Home Affairs and ABF, ‘Commissioner’s Guidelines: Decision making about individual exemptions from Australia’s inwards travel restriction policy’ v.3 and ‘Outward Travel Restrictions Operation Directive’ v.8, no date, available from https://covid19.homeaffairs.gov.au/travel-restrictions [accessed 25 June 2021].

1.11 From April 2020 the Australian Government implemented two additional COVID-19 international travel restrictions in response to public health risks.

- International arrival caps — Following discussion between Australian governments on 10 July 2020, the Australian Government introduced caps on passenger arrival numbers at certain international airports to alleviate pressure on state hotel quarantine programs. The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications (DITRDC) has facilitated the caps by placing conditions on airline timetables under the Air Navigation Regulation 2016 to limit the number of passengers airlines can carry each flight in order to not exceed quarantine caps. As at September 2021, arrival caps were in place for Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide airports.14

- India travel pause — On 30 April 2021, after a steep rise in COVID-19 cases in India, the Minister for Health made a section 477 Biosecurity Act determination to prevent travellers entering Australia by air if they had been in India within 14 days of their flight.15 The ‘India travel pause’ applied to all travellers including Australian citizens, with limited exemptions for crew, diplomats and medical teams, and was in place from 3 to 15 May 2021.

1.12 On 6 August 2021 Australian governments agreed on a plan to transition Australia’s COVID-19 response, which included a commitment to start lifting travel restrictions when 80 per cent of people aged 16 or over were fully vaccinated. On 1 October 2021 the Australian Government announced its intention to begin lifting travel restrictions from November 2021 in line with this plan.

Other COVID-19 international travel measures

Human biosecurity measures at the border

1.13 As the Director of Human Biosecurity under the Biosecurity Act, the CMO has various responsibilities for managing the risk of listed human diseases entering Australia. Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment biosecurity officers and state and territory human biosecurity officers have operational responsibility for human biosecurity measures at the international border. These officers work in partnership with ABF officers, who are responsible for passenger clearance and facilitation.

1.14 Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, additional emergency human biosecurity measures have been introduced to control the risk of COVID-19 transmission through international air travel. In particular, in response to increasing COVID-19 cases in hotel quarantine and the identification of more transmissible COVID-19 strains, on 21 January 2021 the Minister for Health made a section 477 Biosecurity Act determination to require: passengers and crew on incoming international flights to wear face masks; and passengers to provide evidence of a negative COVID-19 test 72 hours prior to flying to Australia.16

1.15 The ANAO is conducting a separate audit examining human biosecurity for international air travel during COVID-19, which is due to table in 2022.

Managing the return of overseas Australians

1.16 Australia’s COVID-19 international travel restrictions have constrained the availability and capacity of international flights. On 17 March 2020 DFAT advised overseas Australians that: ‘If you decide to return to Australia, do so as soon as possible. Commercial options may become less available.’17 During the COVID-19 pandemic, DFAT has been responsible for:

- communicating the risks of overseas travel through its Smartraveller website (https://www.smartraveller.gov.au/);

- providing consular assistance to overseas Australians; and

- assisting Australians to return through facilitated flights.

1.17 The ANAO is conducting a separate audit examining DFAT’s management of the return of overseas Australians in response to COVID-19, which is due to table in 2022.

Timeline of COVID-19 international travel restrictions

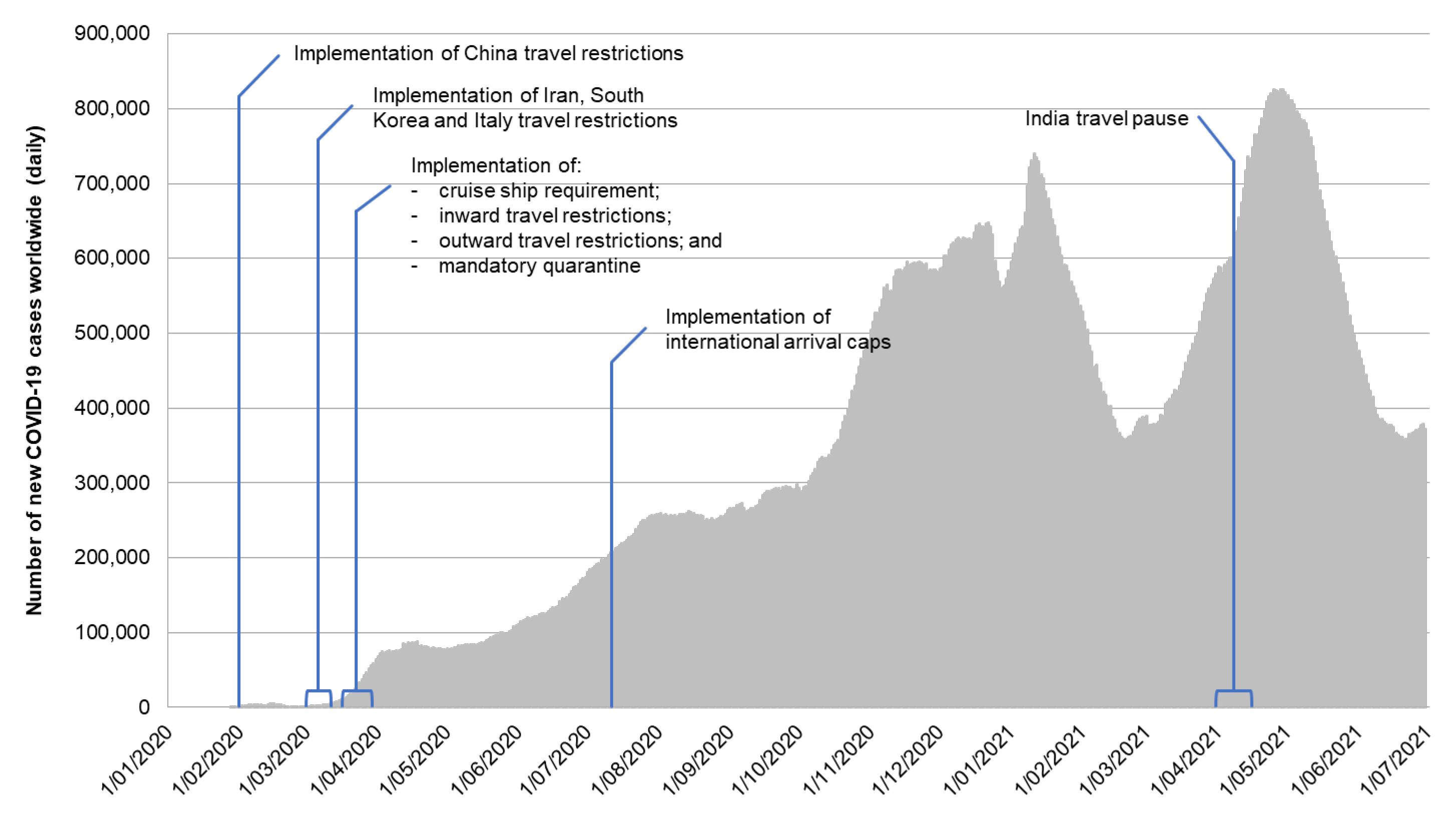

1.18 Figure 1.1 provides a timeline of COVID-19 international travel restrictions, set against a graph of worldwide daily new COVID-19 case numbers. More detail on key events is at Appendix 3.

Figure 1.1: Timeline of COVID-19 international travel restrictions (1 January 2020–30 June 2021)

Source: ANAO analysis. COVID-19 case data from https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases [accessed 6 August 2021].

Public health emergency arrangements

Human biosecurity emergency powers

1.19 Under the Biosecurity Act, after the Governor-General has declared that a human biosecurity emergency exists (section 475), the Minister for Health has broad emergency powers, which cannot be delegated, to determine requirements (section 477) and issue directions (section 478) to control a listed human disease. While there is no requirement for consultation in exercising these powers, the explanatory statement for the human biosecurity emergency declaration stated that the Australian Government had established a protocol that the Minister’s exercise of the powers would be supported by: medical advice from the CMO or AHPPC; consultation with relevant ministers; and, as appropriate, consultation with states and territories.

1.20 Determinations made under section 477 are non-disallowable legislative instruments. As discussed above, during the COVID-19 pandemic the Minister has made several section 477 determinations relating to international travel, including to establish the outward travel restrictions, cruise ship requirement and India travel pause. Before imposing a requirement under section 477, the Minister must be satisfied that:

- it is likely to be effective in, or contribute to, achieving its intended purpose;

- it is appropriate and adapted to achieving the purpose;

- it, and the manner in which it is applied, are no more restrictive or intrusive than required in the circumstances; and

- the period during which it applies is only as long as necessary.18

1.21 Further, the CMO, as Director of Human Biosecurity, has the power to declare a human health response zone under section 113, to which entry and exit requirements apply.

International Health Regulations

1.22 WHO, of which Australia is a member state, has put in place International Health Regulations (2005) (IHRs), which include several articles relevant to international travel:

- Article 20 — which requires member states to develop and maintain capacities at airports and ports to undertake appropriate human biosecurity measures;

- Articles 23 and 30 to 32 — which outline the scope of health measures that can be applied by member states to travellers upon entry;

- Articles 25 and 28 — which prohibit member states from preventing the arrival of ships and aircraft due to public health concerns; and

- Article 40 — which prohibits member states from charging travellers (except for travellers seeking temporary or permanent residence) for health measures such as vaccination, isolation and quarantine.

1.23 Article 43 of the IHRs allows member states to implement additional health measures during a public health emergency of international concern that equal or go beyond WHO recommendations and which would otherwise be prohibited under the IHRs (including under Articles 25 and 28). Any such additional measures must be:

- applied in a transparent and non-discriminatory manner;

- implemented in accordance with the member state’s national law and international law obligations;

- no more restrictive of international traffic, invasive or intrusive than reasonable alternatives;

- based on scientific principles and scientific evidence of health risk; and

- reviewed within three months of implementation.19

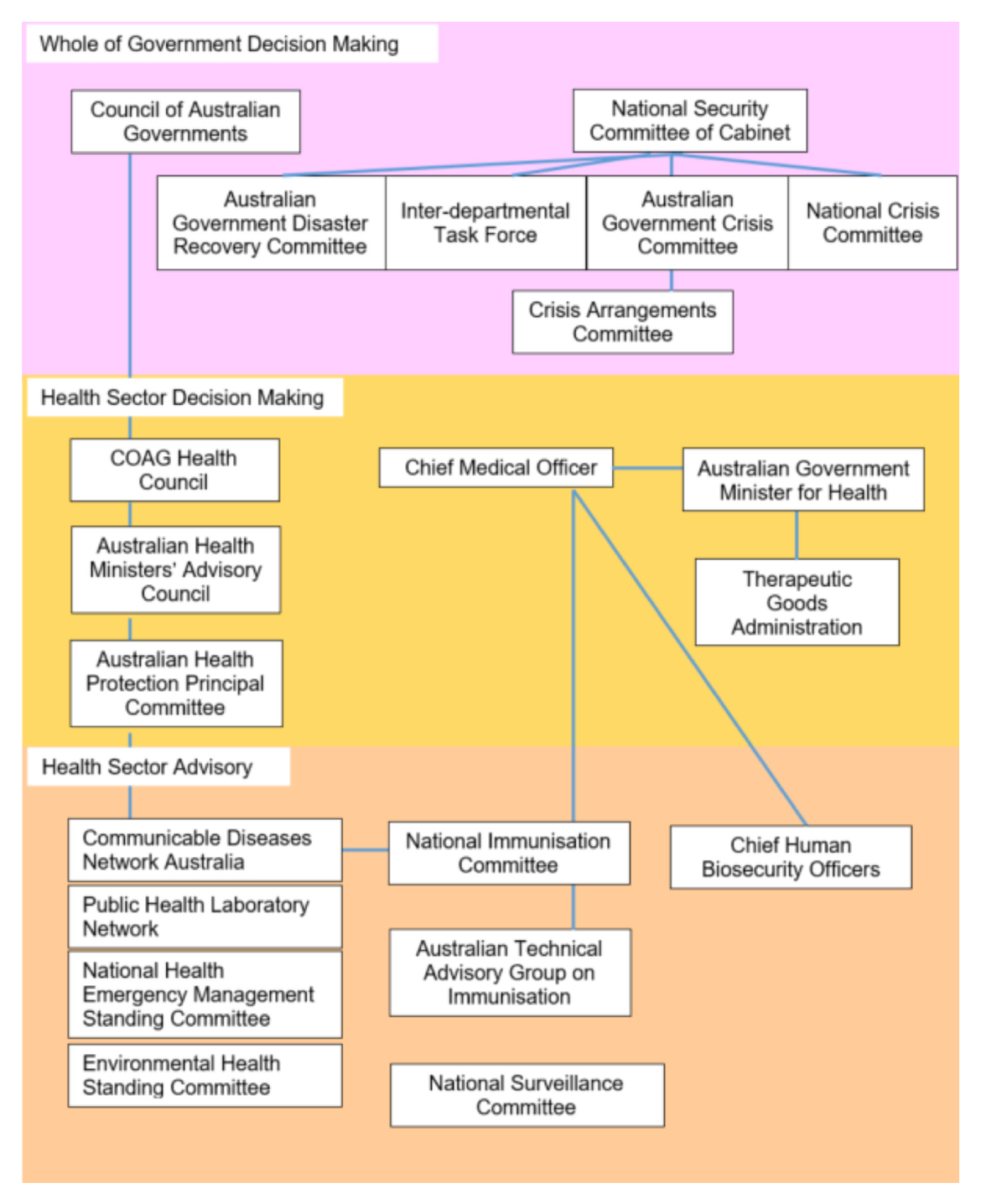

Whole-of-government emergency management arrangements

1.24 The Australian Government Crisis Management Framework (AGCMF), published by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C), sets out standing arrangements for coordinating whole-of-government emergency responses within the Australian Government. Under the AGCMF, the Minister for Health is the lead minister for a domestic public health incident that requires a whole-of-government response, Health is the lead entity and the CMO is the lead senior official.

1.25 Health developed a disease-specific plan in February 2020, the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus, to guide the Australian health sector response, which refers to the governance and coordination arrangements in the AGCMF.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.26 The COVID-19 pandemic and the pace and scale of the Australian Government’s response impacts on the risk environment faced by the Australian public sector. This performance audit was conducted under phase two of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that focuses on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.20

1.27 Australia’s COVID-19 international travel restrictions have affected individuals and businesses, including Australia’s international tourism, travel, aviation and education sectors. Accordingly, there has been significant Parliamentary and public interest in the Australian Government’s management of travel restrictions. The audit was conducted to provide independent assurance to Parliament that travel restrictions have been managed effectively.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.28 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the management of international travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.29 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Have Australia’s COVID-19 international travel restrictions been informed by robust planning and policy advice? (Chapter 2)

- Have effective arrangements been established to manage Australia’s COVID-19 international travel restrictions? (Chapter 3)

- Have inward and outward travel exemptions been managed effectively? (Chapter 4)

1.30 The audit focussed on policy advice to the Australian Government on international travel restrictions and the Australian Government’s management of the inward and outward travel restrictions and international arrival caps to 30 June 2021. The audit did not examine: the management of human biosecurity at the border or the return of Australians from overseas, as these topics are being examined in separate ANAO audits; the management of state and territory quarantine programs or domestic border closures; or the management of the reopening of international borders.

Audit methodology

1.31 The audit involved:

- reviewing submissions and briefings to government;

- reviewing other entity documentation, including meeting papers and minutes, policies and procedures, and correspondence;

- analysing administrative data held in entity systems, including international travel movement records and travel exemption requests;

- testing exemption decisions and border controls for the inward and outward travel restrictions;

- discussions with officers from relevant business areas within DFAT, DITRDC, Health, Home Affairs and PM&C;

- discussions with officers from state and territory government entities; and

- reviewing 1475 contributions received by the ANAO from organisations and individuals.

1.32 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $652,000.

1.33 The team members for this audit were Daniel Whyte, Alicia Vaughan, Michael McGillion, Samuel Jones, William Richards, Leah Chappell, Graeme Corbett and Deborah Jackson.

2. Planning and policy advice

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether Australia’s COVID-19 international travel restrictions have been informed by robust planning and policy advice.

Summary of key findings

Australia did not have a plan to implement international travel restrictions and mass quarantine in response to a pandemic as health experts had concluded that such measures were not effective. Subsequent decisions on implementing COVID-19 international travel restrictions have largely been informed by robust planning and policy advice.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at: clearly communicating border clearance processes; and conducting appropriate planning relating to implementing international travel restrictions and mass quarantine in a future pandemic.

2.1 Robust policy-making processes and advice support effective government decision-making. The Cabinet Handbook states that in upholding the Cabinet guiding principles and operational values, ministers must ‘ensure that proposals prepared for Cabinet consideration have involved thorough consultation across Government, are timely and of high quality, and provide concise and robust advice on implementation challenges and risk mitigation strategies’.21 The Australian Public Service (APS) has traditionally played a key role in support of ministerial decision-making, with subsection 10(5) of the Public Service Act 1999 providing that: ‘The APS is apolitical and provides the Government with advice that is frank, honest, timely and based on the best available evidence.’22 These are the general characteristics of impartial and robust policy advice.

2.2 Drawing on the lessons of past APS experience, the Australian Public Service Commission’s 2015 Learning from Failure report observed that good advice should be: responsive and timely; factually accurate, supported by evidence and shaped by experience; informed by a range of perspectives; and written down. On the question of ministerial decision-making, it highlighted that ‘Cabinet decisions must be made with eyes wide open to risk’ and that ‘informed decision making requires assessment of the specific risks being accepted and the broader context’.23

2.3 This chapter examines whether sufficient planning was undertaken prior to the introduction of Australia’s COVID-19 travel restrictions, and whether the Australian Government received frank, honest, timely and evidence-based policy advice on these measures over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic to 30 June 2021. The chapter focusses primarily on the roles of:

- the Department of Health (Health), as the lead entity for human biosecurity management; and

- the Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs), as the lead entity for emergency management and border control.

Did pandemic planning include adequate consideration of travel restrictions and quarantine?

Following a 2019 Health expert review, which concluded that the use of international travel restrictions and mass quarantine of arrivals to control a pandemic should not be attempted, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic Australia did not have any planning in place to support the implementation of such measures.

2.4 Article 13 of the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHRs) requires Australia to develop and maintain ‘the capacity to respond promptly and effectively to public health risks and public health emergencies of international concern’.24 The World Health Organization (WHO) has stated that: ‘Advance planning and preparedness to ensure the capacities for pandemic response are critical for countries to mitigate the risk and impact of a pandemic’.25 In 2017 the WHO undertook an assessment of Australia’s implementation of the IHRs and found Australia had a ‘comprehensive system of capabilities and functions to prepare, detect and respond to health security threats’.26

2.5 Under the Australian Government Crisis Management Framework (AGCMF), Health is the lead entity for a domestic public health emergency response, and Home Affairs is responsible for coordinating whole-of-government crisis planning and maintaining a national exercise program.27

2.6 The Senate Select Committee on COVID-19’s First Interim Report, published in December 2020, found that ‘pandemic planning pre-COVID-19 was inadequate’ and Health’s February 2020 Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19 Plan) ‘contained key gaps, including failures to contemplate the closure of international borders’.28

Department of Health’s pandemic planning prior to COVID-19

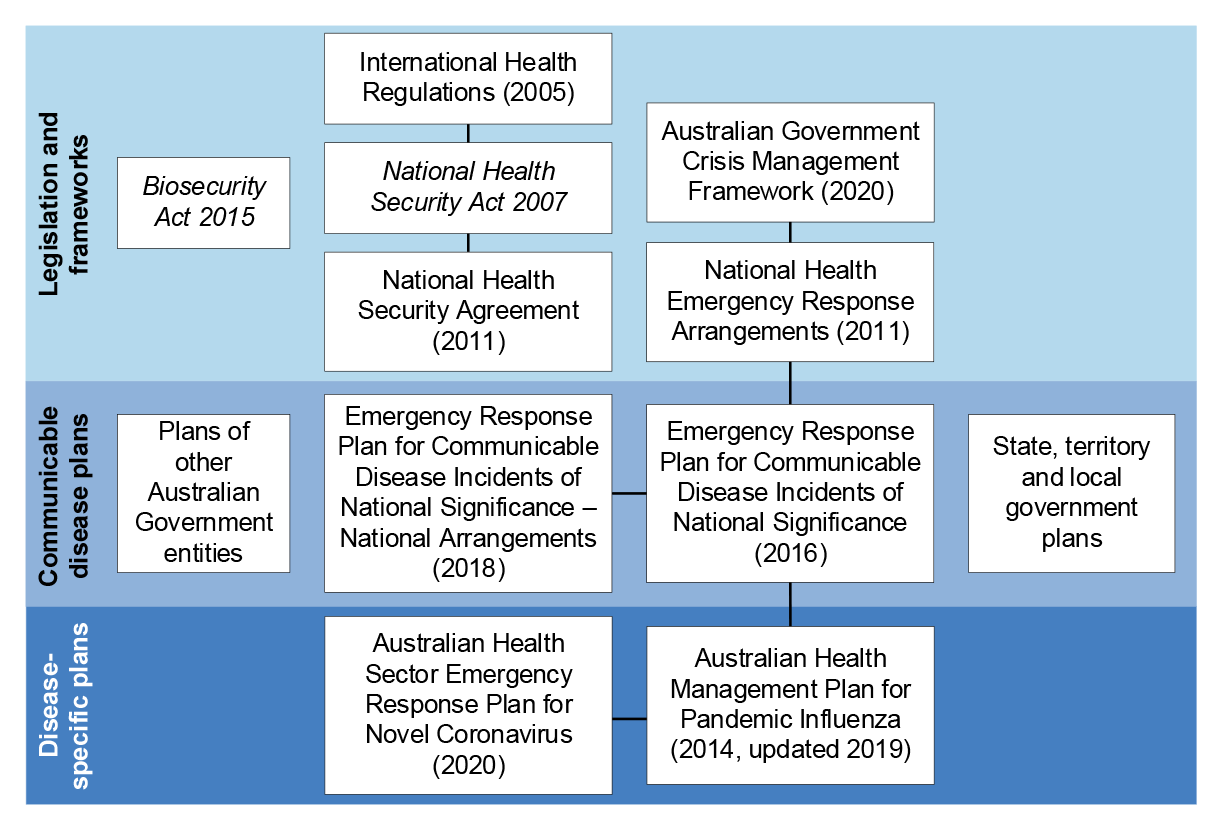

2.7 Health’s responsibilities in relation to communicable disease emergencies are established in legislation and agreements. National plans have also been developed to coordinate responses to communicable disease emergencies. These arrangements are summarised in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Legislation, frameworks and plans relevant to COVID-19

Source: Updated from Auditor-General Report No.57 2016–17 Department of Health’s coordination of communicable disease emergencies, p. 18.

2.8 At the highest level, legislation and frameworks establish governance, coordination and information sharing arrangements for responding to public health emergencies and include some sections of relevance to travel restrictions and quarantine.

- As discussed at paragraphs 1.19 to 1.23, the Biosecurity Act 2015 (Biosecurity Act) contains broad human biosecurity emergency powers that can be used to control a listed human disease and the IHRs include articles relevant to international travel restrictions and quarantine.

- The National Health Security Agreement (2011) states that ‘quarantine activities… are the responsibility of the Commonwealth’ and ‘the Commonwealth has primary responsibility for… responding to public health events occurring at international borders’.29

- The National Health Emergency Response Arrangements (2011) state that ‘the Commonwealth Government will assume costs for a national border health response’ and notes that ‘states and territories have concurrent legislative powers with the Commonwealth with respect to quarantine’.30

2.9 At the next level there are two ‘all hazards’ communicable disease plans that operate in parallel to guide the health sector response and national response. Neither plan includes detailed consideration of travel restrictions or mass quarantine, although the Emergency Response Plan for Communicable Disease Incidents of National Significance (September 2016) notes that measures available under the Biosecurity Act include travel restrictions and isolation measures.

2.10 Sitting beneath the communicable disease plans are disease-specific plans. Of the disease-specific plans in place prior to the onset of COVID-19, the Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza (2019) (AHMPPI) was relevant to the COVID-19 pandemic response. It was used as the basis for the COVID-19 Plan, as ‘key committees and expert groups… agreed the approach and activities of the AHMPPI are relevant and broadly applicable to the novel coronavirus outbreak’.31 Health informed the ANAO that influenza was considered the communicable disease most likely to cause a public health emergency of national significance, so much of its pandemic planning activities prior to COVID-19 had been devoted to it.

Planning for an influenza pandemic

2.11 Since 1999 the Australian, state and territory governments have developed a series of pandemic plans to guide a national response to an influenza pandemic. Appendix 4 shows national plans that have been in operation since 2005 and border measures that were referenced within them.

2.12 The Australian Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza (June 2005) states that:

Australia, being an island nation, has a greater opportunity than other countries to prevent or delay the entry of pandemic influenza into Australia, as it did in 1918. Accordingly, the Government is prepared to implement border measures with this objective.32

This statement was included in the National Action Plan for Human Influenza Pandemic (July 2006, updated April 2009), which also states that: ‘In some situations, large numbers of people arriving at the border may need to be quarantined to prevent transmission of pandemic influenza.’33

2.13 The FLUBORDERPLAN — National Pandemic Influenza Airport Border Operations Plan (February 2009) discussed the potential use of inward and outward travel restrictions, stating that: ‘The decision to close borders is a major one which will be made by the Prime Minister taking into account a wide range of economic, political and social factors.’34 The plan noted that the purpose of border control measures was to delay the arrival or minimise transmission of the pandemic virus and any such measures would only be implemented for a limited duration.

2.14 During 2009, shortly after the FLUBORDERPLAN was published, Australia’s preparedness for an influenza pandemic was tested by the 2009 ‘swine flu’ (H1N1) pandemic. Border measures implemented during the H1N1 pandemic included inflight announcements, border nurses, non-automatic pratique35, health declaration cards, thermal scanners, public health messages and quarantine of symptomatic non-residents identified at the border, but did not include mass quarantine of arrivals or travel restrictions.

2.15 In 2011 Health published the Review of Australia’s Health Sector Response to Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 – Lessons Identified (H1N1 Review), which contained findings relating to border measures, including that:

- border measures continued beyond the establishment of local transmission in Australia and it was not clear when to discontinue border interventions;

- maintaining border measures and undertaking consequent contact-tracing activities placed a heavy burden on jurisdictional public health resources;

- the effectiveness and rationale for border measures needed further consideration;

- policy and operational plans for managing quarantine had not been finalised, both at state and territory and national level, when the pandemic emerged; and

- roles and responsibilities of all governments for quarantine during a pandemic needed to be clarified.

2.16 In October 2012, in response to the H1N1 Review, Health commissioned a series of literature reviews to consolidate evidence on the effectiveness of response measures to inform future pandemic preparedness planning. The review of border measures found:

Border measures—either travel restrictions, or quarantine and isolation—can theoretically delay the peak of the epidemic curve, but in most simulations, only by a maximum of a few weeks. The objective of controlling transmission by delaying introduction, delaying the peak incidence, reducing the peak incidence or increasing the time course of an epidemic are not feasible using currently available methods. Considering this evidence, using border measures to achieve such an objective should not be attempted.36

2.17 While the overall conclusion was that travel restrictions should not be attempted, the literature review noted that they ‘could be considered’ for a disease with high severity and moderate transmissibility that is infectious when asymptomatic.37

2.18 The AHMPPI was last updated in August 2019, after the literature review findings, and does not include any reference to travel restrictions or mass quarantine of arrivals. The FLUBORDERPLAN, which included reference to such measures but had become out of date, was decommissioned in 2019. Consequently, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Australia did not have any current planning in place to support the implementation of travel restrictions or mass quarantine of arrivals in response to a communicable disease pandemic.

Pandemic exercises

2.19 Pandemic exercises involve simulating a pandemic incident to train staff, test roles and responsibilities, confirm capabilities and identify and address any gaps in preparedness. In 2006 Health commenced its first major exercise (Exercise Cumpston) to test the capacity of the Australian health system to prevent, detect and respond to an influenza pandemic in accordance with the 2005 Australian Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza.38 Since then Health has led or been involved in eight additional pandemic exercises (see Appendix 5). While these exercises have considered pandemic response arrangements at a high level, no exercise since Cumpston has tested implementation of border measures.39

2.20 In 2013 the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and Ageing’s Diseases have no borders inquiry report found Australian governments had comprehensively prepared for pandemic influenza, but noted a concern about the extent to which influenza pandemic plans could be used for a non-influenza pandemic. It recommended the Australian Government undertake pandemic exercises to test the response to an infectious disease other than influenza. In 2018 the Australian Government noted the recommendation, stating in its response that recent outbreaks of Ebola, Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome and Zika had provided ‘real-life tests’ of pandemic response plans.

Department of Home Affairs’ pandemic planning prior to COVID-19

2.21 Following the creation of the Home Affairs Portfolio in December 2017, the Secretary of Home Affairs requested a ‘stress test’ be conducted to explore how Home Affairs would support Health during a national health crisis. Home Affairs led the stress test in February 2018, which included participants from Home Affairs, Health, Attorney-General’s Department, Australian Federal Police, Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, Department of Defence, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C).

2.22 The stress test was designed to clarify the role of Home Affairs in a health pandemic and was based on a scenario involving a pandemic-scale outbreak of H7N9 influenza virus commencing in China with escalating severity over a nine-month period. Home Affairs’ report on the stress test concluded:

… current systems and arrangements sufficiently manage and mitigate the impact of ordinary crises, however, a very significant or near-existential crisis would push current arrangements beyond their limits.

2.23 The report noted that caution was needed when considering entry screening and quarantine, stating:

Australia’s reliance on trade means that the economic and social costs of closing the border during an influenza pandemic would most likely outweigh its benefits…

The scenario used in the Stress Test, which focused on border closure and metropolitan quarantine elicited vigorous discussions among participants, with Health advising strongly against border closures and quarantines during a large-scale influenza pandemic. Since the enactment of the [Biosecurity] Act in 2016, relevant provisions have not yet been used.

2.24 In late February 2018 the Home Affairs Secretary requested that the Minister for Home Affairs be briefed on the outcome of the stress test. While a draft ministerial submission was prepared, it was not provided to the Secretary or Minister. Annotation on the draft submission indicates the Deputy Secretary responsible for its clearance was concerned it highlighted ‘significant concerns not being, or not able to be, addressed’. Home Affairs provided a submission to the Minister on the pandemic stress test in April 2020, after the onset of COVID-19, which outlined its key findings and actions that had been undertaken to address them.

Pandemic planning conducted in early 2020

2.25 On 1 February 2020, in correspondence with the Prime Minister, Home Affairs Minister and Cabinet Secretary, the Home Affairs Secretary stated Australia’s whole-of-government civil contingency planning was ‘outdated and not fit for purpose’. The next day Home Affairs began working with Health on planning for ‘an extreme national catastrophic pandemic disaster’. The resulting plan was domestically focussed and did not include planning for travel restrictions or mass quarantine of arrivals. Scenario planning conducted by Home Affairs and Health was consistent with the Health literature review finding (discussed at paragraph 2.16) that border controls would not be effective in preventing importation to Australia.

2.26 In February 2020 Health published the disease-specific COVID-19 Plan, which was largely based on the 2019 AHMPPI. Despite having been developed after the Australian Government had introduced the China travel restrictions, the plan does not include any specific reference to travel restrictions. The plan includes border measures such as ‘enhanced entry screening, non-automatic pratique, [and] preventative biosecurity measures’ as a category of action that could be considered during the ‘initial action’ phase. It also includes reference to ‘quarantine of repatriated nationals and approved foreign nationals as required’ in the initial and targeted action phases, but does not outline which level of government would be responsible.40

Was robust advice provided to the Australian Government on public health, legal and other risks to inform the initial design of travel restrictions?

Expert advice on public health risks was largely provided to inform decisions on the initial design of Australia’s international travel restrictions, although early advice did not recommend implementing travel restrictions. Advice on legal risks was obtained for all travel restrictions. Home Affairs informed the ANAO it provided verbal advice to the Government from February 2020 on the legal risks of the inward travel restrictions, but could not demonstrate that it provided timely written advice.

2.27 In early March 2020, after noting that the extraordinary human biosecurity powers in the Biosecurity Act had never been used, the Australian Government agreed a protocol outlining steps the Minister for Health would take before making a determination, including receiving expert health advice from the CMO or Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC).

Advice on public health risks

2.28 Table 2.1 summarises the sources of advice on public health risks to Australian Government decision makers for travel restriction decisions. The main sources of advice were the CMO, AHPPC, Communicable Disease Network of Australia (CDNA, a subcommittee of AHPPC), Health and Home Affairs. Advice on public health risks is discussed in more detail below. Health’s notifications to the WHO on the public health rationale for border measures is outlined in Appendix 6.

Table 2.1: Sources of public health advice to the Australian Government for Australia’s COVID-19 travel restrictions (introduced before October 2021)

|

Travel restriction |

Source of public health advice |

Date of advice |

Decision maker |

Date of decision |

|

Inward travel restrictions (Australian Government) |

||||

|

China |

AHPPC |

1 February 2020 |

Australian Government |

1 February 2020 |

|

Iran |

AHPPC |

29 February 2020 |

Australian Government |

29 February 2020 |

|

South Korea |

CDNA & AHPPC |

4 March 2020 |

Australian Government |

5 March 2020 |

|

Italy |

AHPPC |

10 March 2020 |

Australian Government |

11 March 2020 |

|

All country inward restrictions |

CDNA & AHPPC |

18 March 2020 |

Australian Government |

19 March 2020 |

|

Cruise ship requirement (Australian Government) |

||||

|

Initial cruise ship requirement |

Home Affairs, with input from AHPPC |

15 March 2020 |

Australian Government |

15 March 2020 |

|

Cruise ship requirement (Biosecurity Act) |

CMO |

16 March 2020 |

Minister for Health |

18 March 2020 |

|

Other Australian Government travel restrictions |

||||

|

Outward travel restrictions |

CMO & Home Affairs Secretary |

25 March 2020 |

Minister for Health |

25 March 2020 |

|

International arrival caps |

a |

a |

Prime Minister |

10 July 2020 |

|

India travel pause |

CMO, Health |

30 April 2021 |

Minister for Health |

3 May 2021 |

|

Mandatory self-isolation and quarantine (state and territory governments) |

||||

|

Mandatory self-isolation |

b |

b |

States & territories governments |

15 March 2020 |

|

Mandatory quarantine |

CMO |

27 March 2020 |

States & territories governments |

27 March 2020 |

Note a: Health’s notification to the WHO noted that the decision was ‘based on the advice of health and policing officials’ in four states (NSW, Queensland, Victoria and WA).

Note b: While there is no evidence of public health advice to the Australian Government for this decision, AHPPC issued a statement on 18 March 2020 that stated mandatory self-isolation was ‘the most important public health measure in relation to case importation’.

Source: ANAO analysis.

Inward travel restrictions (Australian Government)

2.29 On 31 January 2020 the CMO provided advice to the Australian Government that current evidence did not support ceasing flights from China. Later that day the United States introduced an inward travel ban for foreign nationals who had been in China in the past 14 days.

2.30 On 1 February 2020 AHPPC met and recommended that ‘additional border measures be implemented to deny entry to Australia to people who have left or transited through mainland China’. The CMO provided this advice directly to the Australian Government, which agreed to implement the recommendation with immediate effect.

2.31 The implementation of subsequent inward travel restrictions for Iran, South Korea and Italy was partially supported by AHPPC and CDNA advice.

- On 29 February 2020 AHPPC indicated in its advice to the Australian Government that Iran presented ‘a materially greater risk of COVID-19 importation than any other country outside mainland China’. However, it did not recommend travel restrictions as it ‘was concerned that this may set an unrealistic expectation that such measures are of ongoing value for further countries’.41 On the same day the Australian Government decided to implement the Iran travel restrictions based on AHPPC’s risk advice, while noting that AHPPC did not support extending travel restrictions to additional countries at that stage.

- On 3 March 2020 CDNA provided risk analysis to AHPPC that identified China, Iran, South Korea and Italy as high risk countries. On 4 March 2020 AHPPC issued a statement that ‘border measures can no longer prevent importation of COVID-19 and [AHPPC] does not support the further widespread application of travel restrictions to the large number of countries that have community transmission’.42 The Australian Government considered AHPPC’s advice on 5 March 2020 and decided to introduce the South Korea travel restrictions and enhanced screening for Italy.

- On 10 March 2020 AHPPC provided advice to the Australian Government noting that further border restrictions had limited utility but travel restrictions for Italy would be consistent with the recent South Korea travel restrictions decision, given the rapidly increasing case numbers and deaths in Italy. This advice informed the Government’s decision on 11 March 2020 to implement the Italy travel restrictions.

2.32 On 11 March 2020 AHPPC asked CDNA to provide it with further advice on travel restrictions. CDNA met on 16 and 18 March 2020 and agreed on three options to present to AHPPC:

- remove all individual country travel restrictions, noting the implementation of mandatory self-isolation for international arrivals;

- implement travel restrictions for all incoming foreign nationals; or

- implement travel restrictions for the United States and Europe (including the United Kingdom) and consider removing the South Korea travel restrictions.

2.33 On 18 March 2020 AHPPC considered CDNA’s advice and issued the following statement:

AHPPC noted that there is no longer a strong basis for having travel restrictions on only four countries and that Government should consider aligning these restrictions with the risk. This could involve consideration of lifting all travel restrictions, noting the imposition of universal quarantine and a decline in foreign nationals travel, or consideration of the imposition of restrictions on all countries, while small numbers of foreign nationals continue to arrive.43

2.34 On 19 March 2020 the Australian Government was briefed on the AHPPC advice. Later that day, after New Zealand announced it was closing its border to foreign nationals, the Prime Minister, Minister for Foreign Affairs and Minister for Home Affairs announced the decision to implement inward travel restrictions for foreign nationals.

Cruise ship requirement (Australian Government)

2.35 On 9 March 2020 Home Affairs requested advice from AHPPC on the health risks posed by cruise ships and the ability of states and territories to quarantine arrivals. Later that day AHPPC provided advice to Home Affairs, noting that:

- it supported some restrictions on cruise ship arrivals, where applied with enough advance notice for companies to change their itineraries and travellers to change their plans;

- in no case was it advisable to leave people at risk of COVID-19 infection on board a ship, with the preferred option being to disembark people into quarantine or self-isolation; and

- while smaller ships were within the capacity of most jurisdictions to manage, large ships of greater than 1,000 passengers would be beyond the capacity of all jurisdictions without assistance from other states or the Australian Government.

2.36 On 15 March 2020 the Australian Government decided to require international cruise ships to not enter Australian ports for 30 days from midnight on 16 March 2020. Home Affairs’ briefing to government outlined the health risks posed by cruise ships, noting the experience of the Diamond Princess in Japan and Grand Princess in the United States, and referenced AHPPC’s advice.

2.37 On 17 March 2020, in accordance with the Australian Government’s protocol, the Minister for Health received public health advice from the CMO on outlining the risk of transmission on cruise ships seeding widespread onshore transmission. On 18 March 2020 the Minister made an emergency determination under section 477 of the Biosecurity Act to enact the cruise ship requirement.

Outward travel restrictions (Australian Government)

2.38 On 24 March 2020 the Australian Government decided to develop a proposal to prohibit Australian citizens and permanent residents from travelling overseas, with some exceptions for compassionate and essential travel. The Prime Minister announced the outward travel restrictions later that day, noting it would ‘help avoid travellers returning to Australia with coronavirus and the risks of spreading coronavirus to other countries’.44

2.39 On 25 March 2020 the Secretary of Home Affairs and the CMO wrote to the Minister for Health recommending making a section 477 determination under the Biosecurity Act, to prevent overseas travel by Australian citizens and permanent residents. The public health rationale outlined in the CMO’s letter was that:

The increases in Australia’s case numbers continue to be significantly impacted by imported cases as a result of international travel. As worldwide case numbers increase, and the countries reaching the peak of their epidemic curve change, it is impossible to manage the risk of imported case through targeting specific countries.

Further, the Secretary of Home Affairs advised that:

Travel between countries places Australians at risk of exposure to COVID-19 and could then contribute to the spread of COVID-19, including by placing additional pressure on Australia’s health system by travellers upon return to Australia who have COVID-19.

2.40 The Minister made the outward travel determination on the same day.

International arrival caps (Australian Government)

2.41 On 10 July 2020 the Prime Minister agreed at a meeting of Australian governments to introduce a national approach to managing incoming international passengers, based on jurisdictional quarantine capability and the number of incoming passengers. Health’s subsequent notification to the WHO on 21 July 2020 stated that the measure was introduced in response to requests from states and was based on the advice of health and policing officials in those jurisdictions. There is no evidence that the CMO or AHPPC provided advice to inform the Prime Minister’s decision.

India travel pause (Australian Government)

2.42 After AHPPC members noted a significant increase in overseas acquired cases considered to have originated from India, at a meeting on 22 April 2021 Australian governments agreed that action be taken to reduce the number of passengers arriving from India. On 27 April 2021 the Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign Affairs announced a two-week pause on flights between Australia and India.45 On 30 April 2021 the CMO wrote to the Minister for Health to inform the minister’s decision on a section 477 determination under the Biosecurity Act requiring that people not enter Australia if they had been in India in the preceding 14 days. The CMO’s advice noted:

- COVID-19 case numbers in India were increasing rapidly and were likely under-reported;

- over 50 per cent of overseas acquired cases in international arrivals since mid-April 2021 were acquired in India, with a high proportion of variants of concern and variants of interest among those cases; and

- community transmission was occurring within hotel quarantine.

2.43 In addition, the CMO’s advice stated that:

Each new case identified in quarantine increases the risk of leakage into the Australian community through transmission to quarantine workers or other quarantined returnees and subsequently into the Australian community more broadly. This quarantine ‘leakage’ presents a significant risk to the Australian community.

Mandatory self-isolation and quarantine (state and territory governments)

2.44 Quarantine and self-isolation requirements were introduced for passengers arriving from China, Iran, South Korea and Italy when implementing inward travel restrictions for these countries. On 11 March 2020 AHPPC stated that ‘travel restrictions and self-quarantine measures implemented by the Australian Government have been successful in reducing the number of cases detected in Australia and delaying the onset of community transmission’.46

2.45 On 15 March 2020 Australian governments agreed to impose universal self-isolation for all passenger arrivals to Australia. While this decision was not directly informed by AHPPC or CMO advice on public health risks, on 18 March 2020 AHPPC stated that it ‘strongly supported the continuation of a 14-day quarantine requirement for all returning travellers, as the most important public health measure in relation to case importation’.47 On 22 March 2020 AHPPC also stated that:

The continued growth of cases in returned travellers (including the Ruby Princess) necessitates even stronger action on enforcing the quarantine of any returned traveller, with phone checks, mobile phone tracking and other measures.48

2.46 On 26 March 2020 the CMO emailed the Secretary of Home Affairs and the Australian Border Force (ABF) Commissioner noting a concern that the ‘great majority of our new COVID-19 cases are still returned travellers’ and stating he was ‘seriously considering whether we should be formally quarantining ALL returned travellers’. The CMO also noted that: ‘There must be a lot of empty airport hotels and we could take everyone straight to a designated hotel and keep them there for 2 weeks. States and Territories would have to provide the Health services to them’.

2.47 The CMO conveyed this proposal to AHPPC by email on 26 March 2020, noting that mandatory quarantine would take returning travellers out of circulation and allow social distancing to manage the small amount of community transmission within Australia. AHPPC met later that day to discuss the matter, with the meeting outcome noting that each jurisdiction had agreed to quarantine returning travellers where they land. After the meeting the CMO emailed the Secretary of Home Affairs and the Acting Secretary of Health describing AHPPC as strongly supportive of the measure.

2.48 On 27 March 2020 the CMO advised Australian governments that international travellers remained the most significant vector for the spread of COVID-19 in Australia. On this basis, Australian governments agreed that international arrivals be required to undertake mandatory quarantine for 14 days at hotels or other designated facilities from 11:59pm on 28 March 2020.

Advice on legal risk

2.49 Table 2.2 provides an overview of the legal basis for Australia’s COVID-19 travel restrictions as identified in entity records. Measures implemented by the Australian Government relied upon the Migration Act 1958 (Migration Act), Biosecurity Act, Air Navigation Act 1920 (Air Navigation Act) and Air Navigation Regulation 2016 (Air Navigation Regulation). Self-isolation and quarantine requirements have been implemented under state and territory public health legislation.

Table 2.2: Summary of legislative basis for Australia’s COVID-19 travel restrictions (introduced before October 2021)

|

Travel restriction |

Period (to October 2021) |

Legislative basis |

Affected parties |

Exemptions |

|

China restrictions |

1 February–20 March 2020 |

No specific legislative authority (visas may be cancelled under the Migration Act due to health risks) |

Foreign nationals who hold a valid travel authority to enter Australia |

Automatic and discretionary exemptions outlined in policy guidance (see Table 1.1 and Table 1.2) |

|

Iran restrictions |

1–20 March 2020 |

|||

|

South Korea restrictions |

5–20 March 2020 |

|||

|

Italy restrictions |

11–20 March 2020 |

|||

|

Inward travel restrictions |

20 March 2020–present |

|||

|

Outward travel restrictions |

25 March 2020–present |

Emergency determination under the Biosecurity Act |

Australian citizens and permanent residents ordinarily resident in Australia |

Automatic and discretionary exemptions provided in determination and associated policy guidance (see Table 1.1 and Table 1.2) |

|

Cruise ship requirement |

16 March 2020–present |

Cruise ship operators (by extension, cruise ship passengers) |

Automatic and discretionary exemptions provided in determination |

|

|

India travel pause |

3–15 May 2021 |

Travellers from India during period, including citizens |

Automatic exemptions provided in determination |

|

|

International arrival caps |

13 July 2020–present |

Regulatory provisions of the Air Navigation Act |

Airlines flying to Australia (by extension, arriving travellers) |

Additional arrivals may be negotiated outside the caps |

|

Mandatory quarantine |

29 March 2020–present (Note: mandatory self-isolation in place from 16 March 2020) |

State and territory public health legislation |

Arriving travellers, including citizens |

Automatic exemptions agreed by Australian governments Discretionary exemptions administered by states and territories |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Inward travel restrictions

2.50 Home Affairs has identified the basis for the inward travel restrictions in its advice to the Minister for Immigration as follows:

Inwards travel restrictions are implemented through policy, and relate to people who are neither citizens nor permanent residents (or their immediate family). Non-citizens travelling to Australia who are not exempt may be considered for visa cancellation under s116(1)(e) of the Migration Act 1958 (the Act) on the basis that they may present a health risk.

2.51 In a letter to the Prime Minister dated 5 October 2020, the Minister for Home Affairs provided further detail on the basis for the inward travel restrictions, indicating it relies upon:

- public messaging by Government;

- practical impediments (reduced number of international flights and restrictions on arrivals and departures);

- risk for airlines of carrying passengers who they might need to return at their expense if the passenger is not allowed entry to Australia; and

- possible visa cancellation on the basis that the person’s presence in Australia, may be, or would be a risk to the health, safety or good order of the Australian community or a segment of the Australian community.

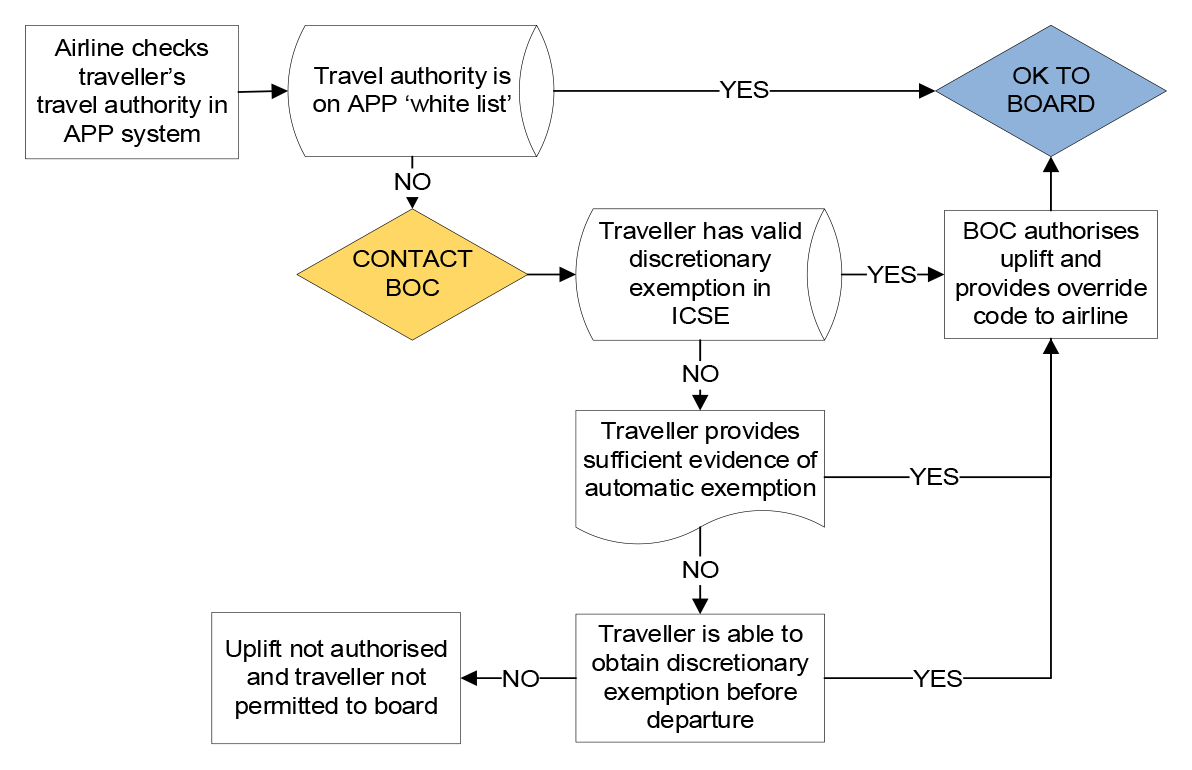

2.52 In February 2020 Home Affairs cancelled the visas of 173 individuals subject to the China travel restriction policy. Home Affairs received 119 requests from visa holders to review these cancellation decisions and 117 of the cancelled visas were subsequently reinstated. Since that time, Home Affairs has not cancelled the visas of travellers attempting to enter Australia without an exemption. Instead, ABF has enforced the inward travel restriction policy by using the Advance Passenger Processing (APP) system to communicate the exemption status of passengers to airlines.

2.53 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, airlines used the APP system to confirm that travellers had legal authority to travel to or from Australia.49 ABF’s guidance to airlines states that:

Airlines must check a passenger’s authority to enter Australia using APP. Where a carrier brings an inadequately documented passenger or an undocumented passenger to Australia, they may be liable, upon conviction, to a fine of AUD22,200.50

During the COVID-19 pandemic the ABF has also used APP to enforce the inward and outward restrictions (ABF’s management of the inward and outward travel restrictions is discussed further in chapter 3 at paragraphs 3.48 to 3.63).

2.54 Between 1 February 2020 and 30 June 2021 ABF used APP to prevent the uplift of close to 4000 foreign nationals attempting to enter Australia without an exemption from the inward travel restrictions. In situations where a non-exempt traveller has mistakenly been authorised uplift, Home Affairs has adopted a policy of granting the traveller an inward travel exemption after the fact.

2.55 Home Affairs informed the ANAO that:

- using APP in this way ‘front end loads’ a judgement about whether foreign nationals can travel to Australia without having their visa cancelled, providing certainty to potential travellers and avoiding the COVID-19 transmission risks of non-exempt travellers presenting at the Australian border;

- ABF only provides advice to airlines about exemption status through APP, and airlines make the decision about whether to board travellers based on a number of factors including ABF advice;

- the Australian Government is not required to afford procedural fairness to non-exempt travellers whose uplift is prevented; and

- while an airline would not face penalties for boarding a non-exempt traveller with a valid visa, it could be required to remove the traveller from Australia and could be liable for the cost of removal if the traveller’s visa was subsequently cancelled.

2.56 However, Home Affairs’ advice to airlines on its website about the inward travel restrictions does not articulate the legislative basis for the inward travel restriction policy and indicates that ABF makes the decision to deny uplift to non-exempt travellers. It states:

From 2100 AEDT 20 March 2020, airline staff should ensure that only exempt travellers board a flight to Australia. Where possible, the Australian Advanced Passenger Processing will be used to deny uplift for all other travellers.51

Home Affairs needs to update its communication to airlines to more clearly outline airlines’ responsibilities under the inward travel restriction policy.

Recommendation no.1

2.57 Department of Home Affairs update its current advice to industry on border clearance processes, and develop guidance for departmental officers for future advice, to ensure that it clearly outlines, where relevant and appropriate:

- legislative basis;

- responsible decision-maker; and

- potential consequences of not following the advice.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.