Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Managing the Privacy of Client Information in Services Australia

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Australians expect government entities to manage their personal information appropriately.

- Services Australia collects, stores and uses the personal information of more than 27 million people to deliver services and payments.

- This audit provides assurance to Parliament about whether Services Australia is effectively managing the privacy of client information.

Key facts

- The Privacy Act 1988 provides the legal framework under which Australian Government entities must operate to protect personal information.

- Government entities must also adhere to the Privacy (Australian Government Agencies — Governance) APP Code 2017.

- Business and government reported 1,113 data breaches in 2024, up from 893 notifications in 2023.

- The Australian Government sector was the second highest for privacy complaints and third highest for notifiable data breaches.

What did we find?

- Services Australia is partly effective in managing the privacy of client information.

- There were partly appropriate arrangements to manage privacy.

- Services Australia was partly effective with implementing arrangements.

- There were deficiencies with risk management, data matching, record-keeping, privacy impact assessments, transparency and reporting.

What did we recommend?

- Five recommendations to Services Australia to improve risk management, data-matching practices, privacy impact assessments, complaints assessment and privacy assurance arrangements.

- Services Australia agreed in principle to one and agreed to four.

- Three recommendations to regulators to review data-matching arrangements, share third-party data breach information and enhanced reporting on privacy. Three were agreed, wholly or in principle.

57

privacy impact assessments completed by Services Australia from 2022–23 to 2024–25.

6042

privacy incidents in Services Australia from 2022–23 to 2024–25.

89

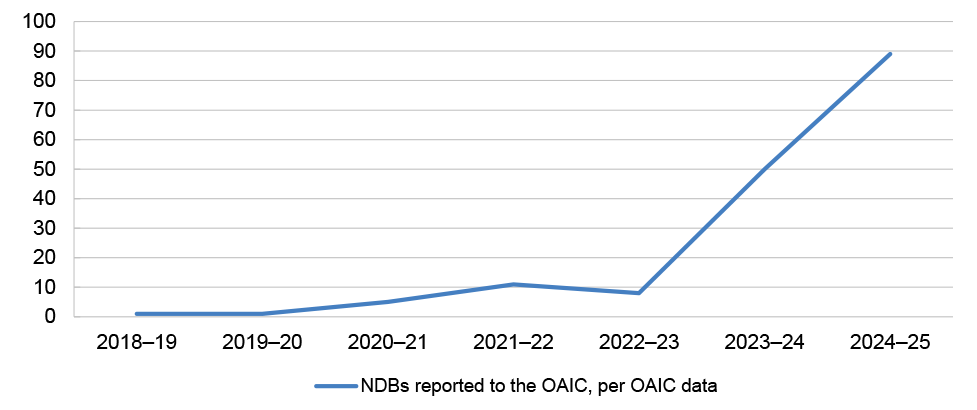

notifiable data breaches reported by Services Australia to the OAIC in 2024–25 (50 in 2023–24).

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Privacy Act 1988 (the Privacy Act) provides the legal framework under which entities and the government must operate to protect personal information. The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC), the national privacy regulator, has stated that:

While individuals can generally choose the private sector organisations with which they share their personal information, they often do not have a choice in providing their personal information to government agencies to access their services. It is essential that government agencies, especially those with service delivery functions, model best practice and build community trust in their ability to protect the security of personal information they hold.1

Rationale for undertaking the audit

2. The Australian community expects that government entities manage personal information appropriately and in accordance with the Privacy Act and other legislative requirements. Consistent with community expectations, the Privacy (Australian Government Agencies — Governance) APP Code 20172 (the APP Code) requires ‘all agencies to strive for best practice in privacy governance so they’re all managing personal information to a consistent high standard’. This ‘helps build public trust and confidence in personal information handling practices and new uses of data proposed by agencies’.

3. In 2023–24, the OAIC reported that the Australian Government sector was the second highest sector for privacy complaints and third highest for notifiable data breaches. In May 2025, the Privacy Commissioner advised that business and government reported 1,113 data breaches in 2024, up from 893 in 2023, noting:

The trends we are observing suggest the threat of data breaches, especially through the efforts of malicious actors, is unlikely to diminish, and the risks to Australians are only likely to increase. Businesses and government agencies need to step up privacy and security measures to keep pace.

4. Services Australia holds data and information on approximately 27.5 million Australians through Medicare, Centrelink and child support services and other programs it delivers on behalf of government. Prior ANAO audits3 and the Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme raised concerns about Services Australia’s management of client information and compliance with the Privacy Act.

The Commission’s findings about the possible breaches of the APPs in the Privacy Act in the Data-matching and exchanges chapter are significant and arise in the context of repeated and voluminous exchanges of personal information and data matches conducted by DHS and the ATO under the Scheme.4

5. This audit was conducted to provide assurance to the Parliament about whether Services Australia is effectively managing the privacy of client information in accordance with the Privacy Act, the APP Code and other legislative requirements.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Services Australia’s management of the privacy of client information.

7. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following two high-level audit criteria.

- Has Services Australia developed appropriate arrangements to manage the privacy of client information consistent with the Privacy Act 1988 and other legislative requirements?

- Has Services Australia effectively implemented arrangements to manage the privacy of client information?

Conclusion

8. Services Australia is partly effective in managing the privacy of client information. It has developed governance arrangements and processes for managing growing privacy risks such as increasing data breaches and cyber-attacks by malicious actors. Within the context of its high-risk privacy environment, its arrangements for managing privacy fall short of its risk profile and emerging risks.

9. Services Australia has developed partly appropriate arrangements to manage the privacy of client information. It has largely appropriate policies in place to meet the requirements of the Privacy Act, however, there are gaps in arrangements to manage privacy risks at the enterprise level. It did not document a rationale or seek legal advice when it decided to no longer undertake data matching under the Data-matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Act 1990.

10. Services Australia is partly effective in implementing its arrangements to manage the privacy of client information. It undertakes privacy impact assessments (PIAs), however, there were record keeping deficiencies, it does not conduct public consultation and does not provide information to the public on its PIAs beyond report dates and titles. There were other gaps with respect to implementation of arrangements including that it: does not analyse data on privacy incidents and complaints to assess risk; has not always been timely in making notifications of notifiable data breaches (NDBs); and has not established an overarching assurance framework setting out how it assures itself that it is effectively managing the privacy of client information.

Supporting findings

Arrangements to manage privacy

11. Services Australia has established largely appropriate governance and oversight arrangements. To meet the requirements established in the APP Code, Services Australia has a Privacy Champion and two Privacy Officers. It has also established a Privacy Contact Officer Network to support the management of the privacy of client information. Reporting on privacy matters is provided to Services Australia’s Security Committee. The Privacy and Personal Information and Release branch assists with processing privacy matters. Services Australia’s privacy management plans include performance measures for the self-assessment of privacy-related activities and have been reviewed annually. Services Australia has a high-risk privacy profile. It has identified that it needs to mature its arrangements to be commensurate with this risk profile, with it not meeting 12 of 21 target maturity ratings for 2024–25. (See paragraphs 2.2 to 2.15)

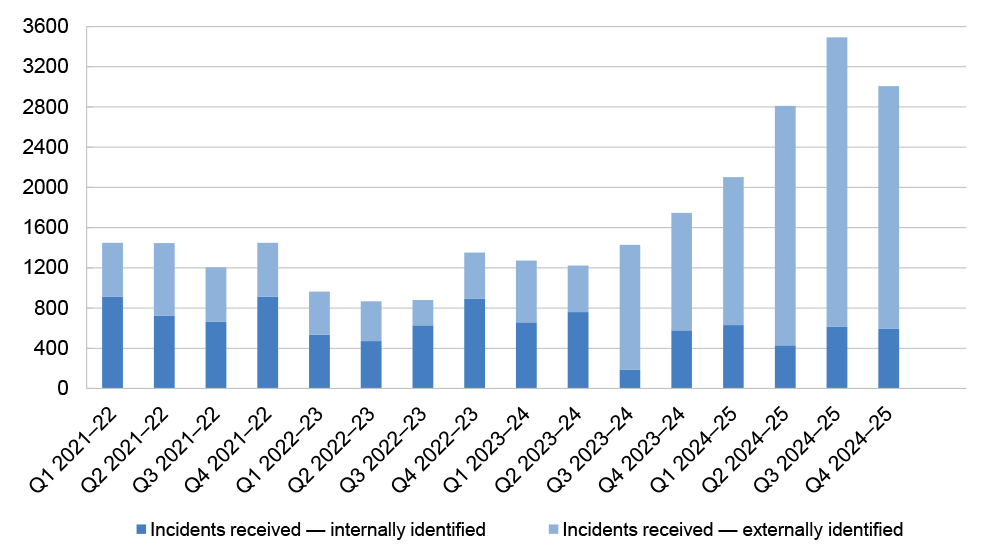

12. Services Australia’s enterprise-level Risk Management Policy and Framework categorises privacy as a ‘specialist risk’. It does not have a privacy risk management plan or privacy specific enterprise risk or risk tolerance statement. Privacy related risks are incorporated in the group risk management plans of the seven service groups. There has been an increase in the volume of data breaches in Services Australia, largely caused by malicious actors. Third parties are not required to notify Services Australia following a data breach involving government identifiers, creating a risk to the timeliness of assessments of these breaches. Services Australia has not developed a technology security risk management plan as required by PSPF Direction 002-2024. (See paragraphs 2.16 to 2.58)

13. Services Australia publishes a privacy policy and privacy notices that largely comply with the requirements of Australian Privacy Principles 1 and 5. Services Australia does not regularly review its public privacy policy and privacy notices. Review of these products would benefit from client input. Services Australia maintains an internal operational privacy policy and ‘operational blueprints’ that provide guidance to staff. The operational privacy policy was reviewed in 2023–24. Services Australia has policies to support individuals access their own information, and to support appropriate data destruction. (See paragraphs 2.59 to 2.78)

14. Services Australia no longer undertakes data matching under the Data-matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Act 1990 and instead follows the voluntary guidelines on data matching in Australian Government administration. This approach reduces transparency and accountability to Parliament. There was no documented rationale or legal advice to underpin this change. Services Australia has not fully implemented Robodebt Royal Commission recommendations relating to data matching. Services Australia has published 13 of 32 data-matching protocols. (See paragraphs 2.79 to 2.109)

15. Services Australia has implemented mandatory induction and refresher training programs for staff on their privacy responsibilities. Training completion rates met the 95 per cent target in 2024. (See paragraphs 2.110 to 2.116)

16. Services Australia produces a monthly executive report and a quarterly privacy dashboard report for its Security Committee and regular reporting to its Audit and Risk Committee. Services Australia does not publicly report on privacy incidents, complaints and notifiable data breaches. (See paragraphs 2.117 to 2.129)

Implementation of arrangements to manage the privacy of client information

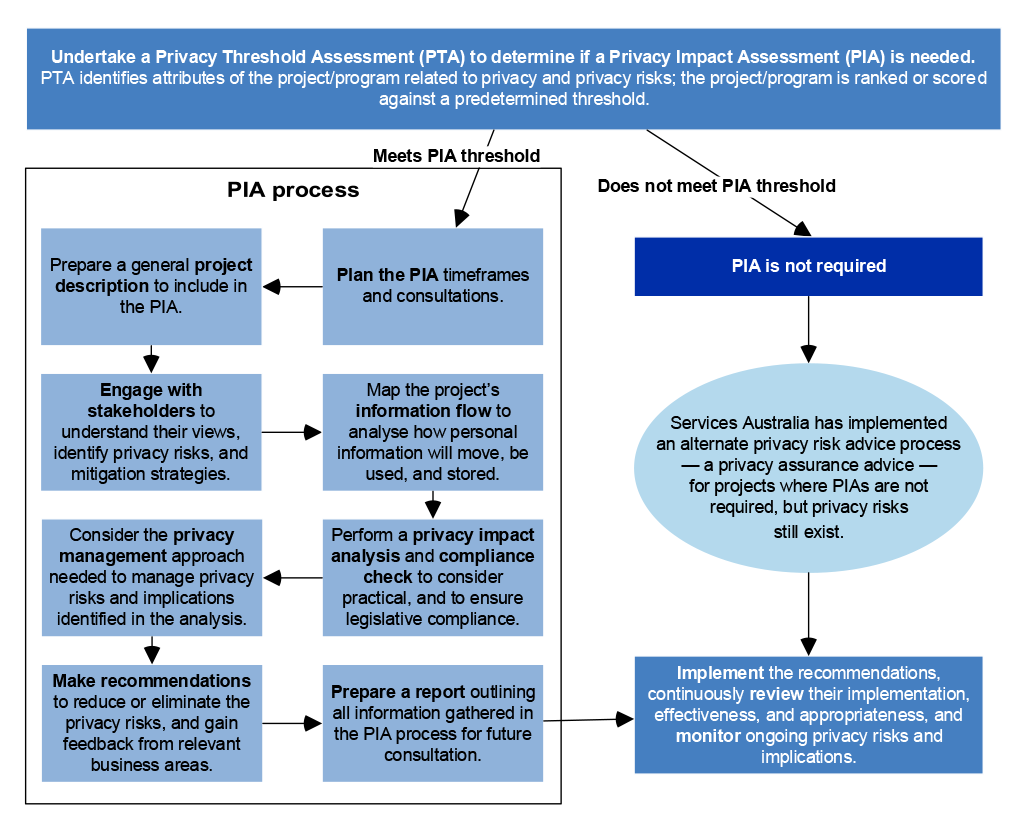

17. Services Australia undertakes privacy threshold assessments (PTAs) for projects involving new or changed information arrangements. Higher risk projects are subject to privacy assurance advice or a privacy impact assessment (PIA). Services Australia appropriately undertakes PIAs, except that none included public consultation. Record keeping of PTAs and PIAs was deficient. Services Australia maintains a public PIA register. It does not publish PIAs. One of the 18 Freedom of Information requests for PIAs since 2020 was successful; 14 were refused on the basis of legal professional privilege. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.28)

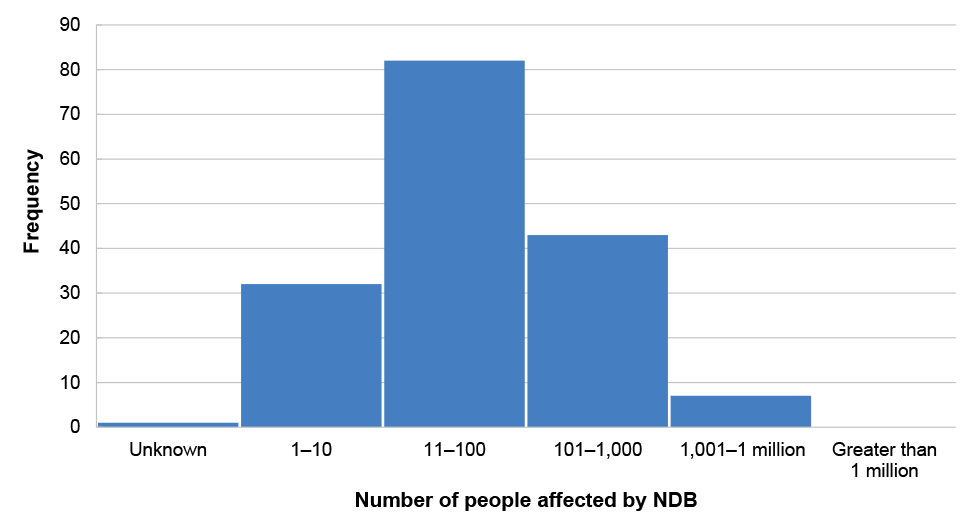

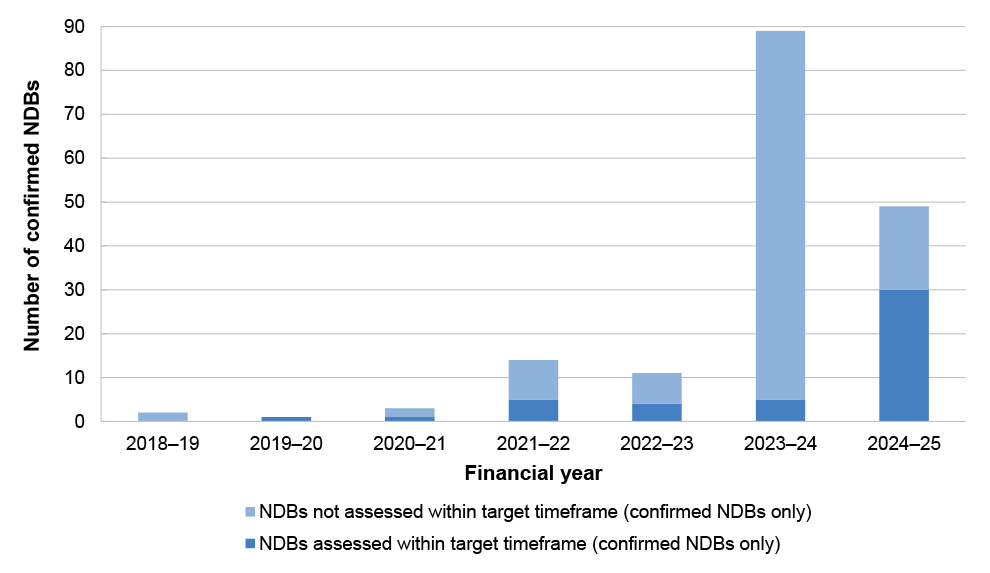

18. Services Australia accepts privacy-related complaints through its complaint’s mechanism. It does not analyse or report on privacy complaints, nor does it use data from privacy complaints to inform its risk assessments. Services Australia did not meet the legislated 30-day requirement for assessing potential NDBs in 2022–23 or 2023–24. It met this requirement in 2024–25. Services Australia did not notify affected individuals and the OAIC in accordance with its internal target timeframes, although performance improved in the first quarter of 2025–26. Services Australia has not documented its approach to assuring that its handling of NDBs complies with the Privacy Act. (See paragraphs 3.33 to 3.60)

19. Services Australia does not have a privacy assurance strategy. There are a range of internal controls and assurance processes, including user access monitoring, quality monitoring of calls and internal audit, that provide assurance over the management of personal information. Services Australia has unresolved ANAO user access controls audit findings which are not being addressed at a pace commensurate with the increasing risks to privacy. (See paragraphs 3.62 to 3.87)

20. Of the 13 recommendations made by the OAIC in three privacy assessments between 2020 and 2023, Services Australia has implemented nine, partially implemented two, and two recommendations were superseded by events. (See paragraphs 3.88 to 3.91)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.34

Services Australia improve the identification, assessment and management of privacy risks by implementing an enterprise-wide privacy risk management plan.

Services Australia response: Agreed in principle.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.53

The Australian Government consider implementing arrangements to support Services Australia being provided with timely notification of third-party data breaches involving government-related identifiers such as Medicare numbers and Centrelink reference numbers.

Attorney-General’s Department response: Agreed.

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.98

Services Australia publish all data-matching program protocols on its website, including dates of operation, and regularly review the currency of the information published, except where an exemption has been sought in accordance with the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner’s voluntary data-matching guidelines.

Services Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 2.104

The Australian Government review existing data-matching activities undertaken by Services Australia and other government entities to assess whether the current frameworks — the Privacy Act 1988, the Data-matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Act 1990, and the voluntary Guidelines on data matching in Australian Government administration — are appropriate for use with contemporary data-matching and information-sharing practices and provide sufficient transparency and accountability.

Department of Social Services response: Agreed in principle.

Attorney-General’s Department response: Noted.

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 2.127

There is limited reporting to the Australian Parliament by Australian Government entities on their compliance with the Privacy Act 1988. Entities are not required to report in annual reports on their management of privacy. The Attorney-General’s Department, in consultation with the Department of Finance as required, consider advice to the Australian Government on options to improve the transparency of entities’ compliance with the Privacy Act 1988.

Attorney-General’s Department response: Agreed.

Department of Finance response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.27

Services Australia improves the conduct and transparency of its privacy impact assessment (PIA) processes by:

- implementing external consultation arrangements for PIAs;

- publishing a description of each PIA on its PIA register;

- implementing arrangements to ensure PIAs are added to its public register in a timely manner;

- reviewing the appropriateness using of legal professional privilege Freedom of Information requests for PIAs; and

- publishing PIA reports to the extent that this does not exacerbate privacy or other risks.

Services Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 3.47

Services Australia undertake analysis and reporting of privacy complaints to understand trends, identify emerging risks and promote continuous improvement in its management of privacy.

Services Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 8

Paragraph 3.86

Services Australia implements a privacy assurance strategy to assess compliance with its privacy obligations.

Services Australia response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

21. The proposed audit report was provided to the Services Australia and extracts were provided to the Attorney General’s Department, the Department of Finance, the Department of Social Services and the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner. Summary responses are reproduced below and full responses are at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

Services Australia

The Agency welcomes the report and notes the report recommendations aimed at further strengthening the Agency’s management of privacy. Protecting privacy is a key part of the Agency’s core business and promotes trust and confidence in the Agency to deliver government services to all Australians. The Agency actively promotes a culture of valuing and protecting information.

Attorney-General’s Department

The department appreciates the important opportunity afforded by this audit to consider the potential for improvements to the legal frameworks and processes governing the handling of Australians’ personal information, in particular, government-related identifiers and Tax File Numbers.

The department supports the Attorney-General to administer the Privacy Act 1988 (Privacy Act), and notes the importance of all regulated entities maintaining strong protections for Australians’ personal information in accordance with the Privacy Act. The department also notes that Government agencies such as Services Australia are subject to the Australian Government Agencies Privacy Code, which has a key objective of enhancing the privacy capability and accountability of agencies.

The department has responded to the three recommendations that pertain to the department’s responsibility for the Privacy Act, including the Notifiable Data Breaches scheme.

Department of Finance

The Department of Finance notes the findings in the report extract.

Department of Social Services

The Department of Social Services (the Department) appreciates and acknowledges the insights and opportunities for improvement outlined in the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) report on Managing the privacy of client information in Services Australia.

The Department agrees in principle with Recommendation 4.

The Department is supportive of an independent review to assess the effectiveness of the Data-matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Act 1990 to determine if it remains fit for purpose for contemporary data-matching and information sharing. The Department is ready to provide support to the review should it go ahead.

An independent review would ensure an arm’s length and publicly transparent evaluation of data-matching activities conducted by Services Australia and other government entities to inform any potential legislative change.

The Department would assume the responsibility of and is committed to, progressing any suggestions that may result from an independent review, including amendments to, or a repeal of, the Data-matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Act 1990.

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner

The OAIC agrees in principle it would be beneficial for Services Australia to be notified of relevant third-party data breaches to enable it to act to prevent future breaches and carry out its functions. Such arrangements could require legislative reform, which is a matter for Government.

If a new reporting obligation is to be imposed it will be necessary to specify the entities to which the requirement applies and the threshold for notification. For example, consideration should be given to whether the obligation rests with third parties to directly notify Services Australia. The OAIC is not notified of all data breaches involving Services Australia or individual identifiers. The Notifiable Data Breaches scheme only requires entities regulated under the Privacy Act to notify the OAIC if a data breach is likely to result in serious harm to an individual.

Data matching activities potentially create significant privacy impacts for individuals. It is important that these activities are conducted in compliance with privacy obligations, and that agencies conducting data matching programs consider and manage privacy impacts during program development.

The OAIC is currently reviewing the voluntary Guidelines on data matching in Australian Government administration. The OAIC will consult relevant agencies during this process.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

22. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Transparency and accountability

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Australian Government collects, stores and uses personal information on every Australian citizen, resident and visitor. Strong privacy practices and policies are important as they influence how Australians think about, and perceive, the trustworthiness of government entities and other organisations.

1.2 The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) has stated that:

While individuals can generally choose the private sector organisations with which they share their personal information, they often do not have a choice in providing their personal information to government agencies to access their services. It is essential that government agencies, especially those with service delivery functions, model best practice and build community trust in their ability to protect the security of personal information they hold.5

Privacy framework

1.3 The Privacy Act 1988 (the Privacy Act) provides the legal framework under which Australian Government entities, private organisations and businesses, and other specified entities6 must operate to protect personal information. The Privacy Act defines ‘personal information’ as:

Information or an opinion about an identified individual, or an individual who is reasonably identifiable:

a) whether the information or opinion is true or not; and

b) whether the information or opinion is recorded in a material form or not.

1.4 Certain types of information constitute personal information under the Privacy Act:

- sensitive information, where this information otherwise meets the definition of personal information, including: health information; information on an individual’s racial or ethnic origin, sexuality, or criminal record; and personal beliefs such as political opinions or religious beliefs;

- credit information, employee record information; and

- tax file number information.7

1.5 The Privacy Act sets out 13 Australian Privacy Principles (APPs) which govern standards, rights and obligations around:

- the collection, use and disclosure of personal information;

- an organisation or agency’s governance and accountability;

- integrity and correction of personal information; and

- the rights of individuals to access their personal information.8

1.6 Australian Government entities are required to handle personal information in accordance with the Privacy Act.9 All entities covered by the Privacy Act are subject to the Notifiable Data Breaches scheme, which requires entities to notify affected individuals and the OAIC when a data breach occurs that is likely to result in serious harm to an individual whose personal information is involved.10

1.7 Australian Government entities must also adhere to the Privacy (Australian Government Agencies — Governance) APP Code 2017 (the APP Code).11 The APP Code is a legislative instrument issued under section 26G of the Privacy Act that requires entities to:

- have a privacy management plan;

- appoint a Privacy Officer, or Privacy Officers, and ensure that the Privacy Officer functions are undertaken;

- appoint a senior official as a Privacy Champion to provide cultural leadership and promote the value of personal information, and ensure that the Privacy Champion functions are undertaken;

- undertake a privacy impact assessment (PIA) for all ‘high privacy risk’ projects or initiatives that involve new or changed ways of handling personal information and which are likely to have a significant impact on the privacy of individuals;

- maintain a register of all PIAs conducted and publish this register, or a version of the register, on their websites; and

- take steps to enhance internal privacy capability, including by providing appropriate privacy education or training in staff induction programs, and annually to all staff who have access to personal information.

Privacy Act review

1.8 The Attorney-General’s Department completed a review of the Privacy Act in 2022, and the Australian Government response was published in September 2023.12 The Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024 (Amendment Act) implemented proposals from the government response to the review. These included expanding the Australian Information Commissioner’s powers, facilitating information sharing in emergency situations or following eligible data breaches, development of a Children’s Online Privacy Code, enhancing protections for certain overseas disclosures of personal information, introducing new tiers of civil penalties, and increasing transparency about automated decisions which use personal information.

National regulator for privacy

1.9 The OAIC is the national regulator for privacy and an independent statutory agency established under the Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010. The OAIC’s functions relate to the protection of the privacy of individuals in accordance with the Privacy Act, resolving privacy complaints and investigating potential data breaches, the provision of guidance on how to handle personal information and the promotion of privacy awareness. Alongside receiving notifications of eligible data breaches (see paragraph 1.6), the OAIC also has a range of regulatory powers, including ‘to work with entities to facilitate legal compliance and best privacy practice, as well as investigative and enforcement powers to use in cases where a privacy breach has occurred’.13

Services Australia

1.10 Services Australia aims to ‘support Australians by efficiently delivering high-quality, accessible services and payments on behalf of government’.14 It collects, stores and uses the personal information of over 27 million clients15 to support the delivery of ‘services and payments related to social security, child support, students, families, aged care and health programs’. Services Australia shares data with the Australian Taxation Office and other entities across the Commonwealth, state and territory jurisdictions, and internationally, to support its own and their functions. At 30 June 2024, Services Australia employed 33,554 people.

1.11 The Australian Public Service Commission’s 2024 Capability Review of Services Australia stated that:

Services Australia has the most frequent and direct interactions with the Australian public compared with any other Australian Government entity. Staff access to population-level personal citizen data is unmatched by any other Commonwealth agency. Staff adherence to the APS frameworks and policies, the Privacy Act 1988 and other legislation protecting privacy and governing sharing and use of citizen data, is integral to upholding integrity in the programs and services they deliver, and helps to build trust with the Australian public.16

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.12 The Australian community expects that government entities manage personal information appropriately and in accordance with the Privacy Act and other legislative requirements. Consistent with community expectations, the APP Code requires ‘all agencies to strive for best practice in privacy governance so they’re all managing personal information to a consistent high standard’. This ‘helps build public trust and confidence in personal information handling practices and new uses of data proposed by agencies’.

1.13 In 2023–24, the OAIC reported that the Australian Government sector was the second highest sector for privacy complaints and third highest for notifiable data breaches. In May 2025, the Privacy Commissioner advised that business and government reported 1,113 data breaches in 2024, up from 893 notifications in 2023, noting:

The trends we are observing suggest the threat of data breaches, especially through the efforts of malicious actors, is unlikely to diminish, and the risks to Australians are only likely to increase. Businesses and government agencies need to step up privacy and security measures to keep pace.

1.14 Services Australia holds data and information on approximately 27.5 million Australians through Medicare, Centrelink and child support services and other programs it delivers on behalf of government. Prior ANAO audits17 and the Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme raised concerns about Services Australia’s management of client information and compliance with the Privacy Act.

The Commission’s findings about the possible breaches of the APPs in the Privacy Act in the Data-matching and exchanges chapter are significant and arise in the context of repeated and voluminous exchanges of personal information and data matches conducted by DHS and the ATO under the Scheme.18

1.15 This audit was conducted to provide assurance to the Parliament about whether Services Australia is effectively managing the privacy of client information in accordance with the Privacy Act, the APP Code and other legislative requirements.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.16 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Services Australia’s management of the privacy of client information.

1.17 To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following two high-level audit criteria.

- Has Services Australia developed appropriate arrangements to manage the privacy of client information consistent with the Privacy Act 1988 and other legislative requirements?

- Has Services Australia effectively implemented arrangements to manage the privacy of client information?

1.18 The audit scope focussed on whether Services Australia’s frameworks and practices comply with the requirements and intent of the Privacy Act, including the APP Code between 2022–23 to 2024–25.

1.19 An assessment of the effectiveness of the OAIC as the national regulator for privacy was outside the scope of this audit. The audit did not consider the management of employees’ personal information.

Audit methodology

1.20 The audit methodology included:

- reviewing Services Australia’s records and data;

- meeting with officers from Services Australia, the OAIC, the Attorney-General’s Department, the Australian Taxation Office, and the Department of Social Services; and

- site visits to Services Australia’s service centres in Woden (ACT) and Tweed Heads (NSW).

1.21 Australian Government entities largely give the ANAO electronic access to records through cooperation, in a form useful for audit purposes.

- Services Australia advised the ANAO in January 2025 that it could not voluntarily provide access to certain record-keeping systems requested by the ANAO due to concerns about its obligations under protected information provisions in legislation, including the Health Insurance Act 1973 and the Migration Act 1958. Services Australia advised that it could not be certain, in providing information access through electronic means, that all legal secrecy provisions could be maintained. The ANAO and Services Australia agreed that ANAO access to those systems would occur on Services Australia premises pursuant to the access provisions of section 33 of the Auditor-General Act 1997.

- The OAIC advised the ANAO that it could not voluntarily provide certain information requested by the ANAO due to concerns about its obligations under section 29 of the Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010. On 21 March 2025 the Auditor-General issued the Australian Information Commissioner with a notice to provide information and produce documents pursuant to section 32 of the Auditor-General Act 1997. Under this notice, the Australian Information Commissioner provided the requested information and documents.

1.22 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $622,108.

1.23 The team members for this audit were Jason Millward, Carina Moeller, Ewan McPherson, Tatenda Zembe and Nathan Callaway.

2. Arrangements to manage privacy

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether Services Australia has developed appropriate arrangements to manage the privacy of client information consistent with the Privacy Act 1988 (the Privacy Act), the Privacy (Australian Government Agencies — Governance) APP Code 2017 (the APP Code) and other legislative requirements.

Conclusion

Services Australia has developed partly appropriate arrangements to manage the privacy of client information. It has largely appropriate policies in place to meet the requirements of the Privacy Act, however, there are gaps in arrangements to manage privacy risks at the enterprise level. It did not document a rationale or seek legal advice when it decided to no longer undertake data matching under the Data-matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Act 1990.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations to Services Australia aimed at: improving privacy risk management; and publishing data-matching protocols. There are three recommendations to other entities to: improve notification to Services Australia of third-party data breaches involving government identifiers; review data-matching arrangements; and enhancing the transparency of Australian Government entities’ management of privacy.

The ANAO also suggested that Services Australia could: engage clients to review its privacy policy and notices; link its operational blueprints to privacy legislation and guidelines; and publish more information about its management of privacy.

2.1 The APP Code requires entities to implement governance arrangements ‘to move towards a best practice approach to privacy governance to help build a consistent, high standard of personal information management across all Australian Government agencies’.19

Has Services Australia established appropriate governance and oversight arrangements for managing the privacy of client information?

Services Australia has established largely appropriate governance and oversight arrangements. To meet the requirements established in the APP Code, Services Australia has a Privacy Champion and two Privacy Officers. It has also established a Privacy Contact Officer Network to support the management of the privacy of client information. Reporting on privacy matters is provided to Services Australia’s Security Committee. The Privacy and Personal Information and Release branch assists with processing privacy matters. Services Australia’s privacy management plans include performance measures for the self-assessment of privacy-related activities and have been reviewed annually. Services Australia has a high-risk privacy profile. It has identified that it needs to mature its arrangements commensurate with this risk profile, with it not meeting 12 of 21 target maturity ratings for 2024–25.

Privacy management plans

2.2 Section 9 of the APP code requires agencies to have a privacy management plan (PMP), and to measure and document performance against the PMP at least annually. The PMP is required to identify ‘specific, measurable privacy goals and targets’, and set out how an agency will meet its compliance obligations under Australian Privacy Principle (APP) 1.2.

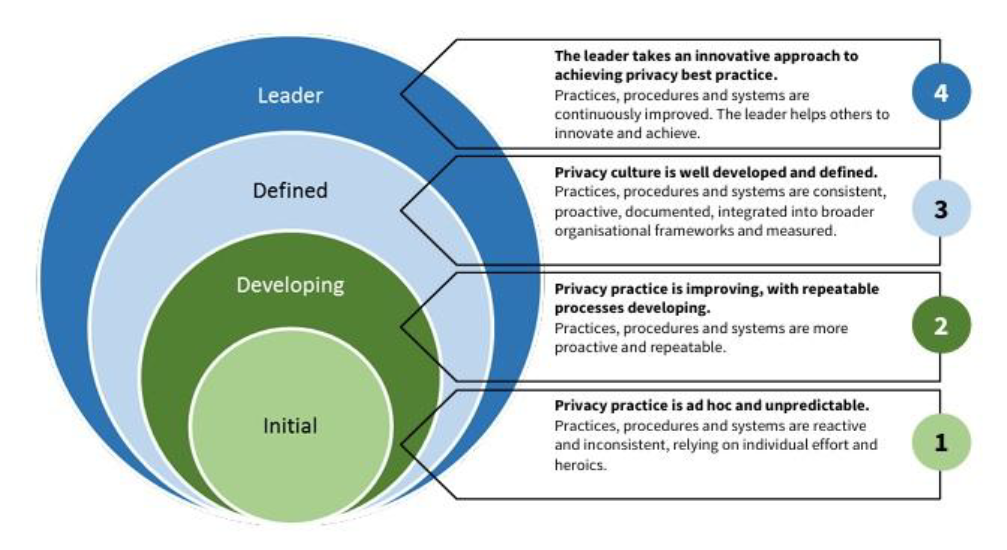

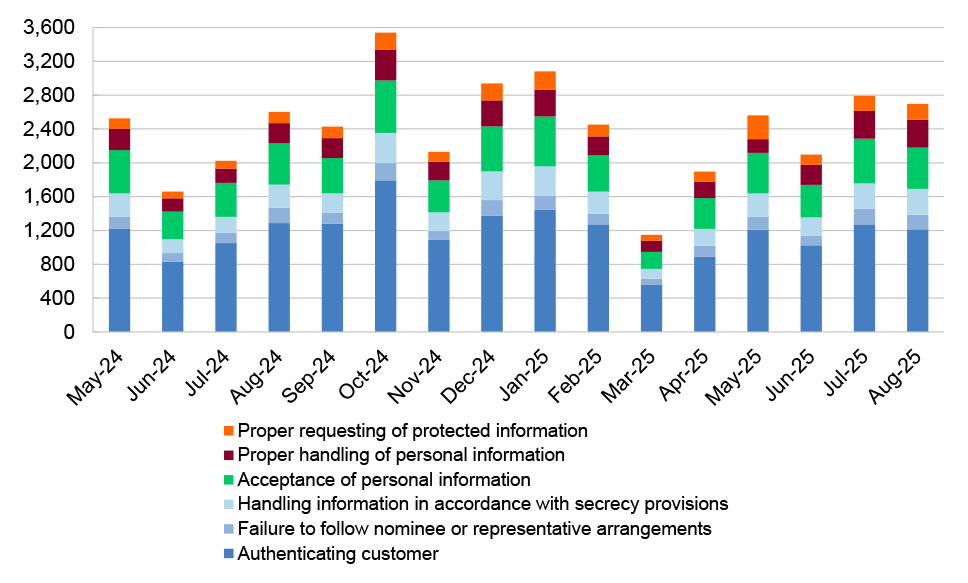

2.3 The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) provides guidance for developing PMPs, including a framework against which entities can assess their privacy maturity across a set of criteria.20 Figure 2.1 describes the maturity levels from the OAIC’s Privacy Program Maturity Assessment Framework (Maturity Framework).

Figure 2.1: Privacy Program Maturity Assessment Framework maturity levels

Source: OAIC, Interactive PMP Explained, July 2018, p. 25.

2.4 Services Australia developed a PMP each year as required by the APP Code. PMPs were informed by OAIC guidance. In PMPs, Services Australia: assesses the current state of its privacy practices; sets privacy goals and targets; and sets out plans to measure its performance regarding the compliance obligations under the Privacy Act. The 2025–26 PMP outlines that ‘[p]rotecting privacy is part of the agency’s core business and promotes trust and confidence in the agency to deliver government services to all Australians’. It also states that it:

[A]dvances Services Australia’s 2030 Vision by strengthening our commitment to delivering simple, helpful, respectful and transparent services through clearly defined, measurable privacy goals that enhance customer trust and service excellence.

2.5 Services Australia uses the OAIC’s template for PMPs. This PMP template is designed to support entities to assess their overall privacy risk maturity profile. Entities are to measure their privacy maturity across five elements: governance and culture; privacy strategy; privacy processes; risk and assurance; and data breach responses. To measure across these five elements, entities assess maturity across 21 ‘attributes’.21

2.6 Services Australia annually self-assesses its prior-year maturity (see Figure 2.1) against the 21 attributes. It uses these assessments to inform subsequent targets and to define activities to be used to achieve PMP outcomes. Appendix 3 shows Services Australia’s self-assessment against each of the 21 attributes in PMPs developed between 2022–23 and 2025–26.

- Against its targets for 2021–22, Services Australia did not meet target maturity ratings for 10 out of 21 attributes.

- Against its 2022–23 targets, it did not meet target maturity for seven of 21 attributes.

- Against its 2023–24 targets, it did not meet target maturity for 20 of 21 attributes.

- Against its 2024–25 targets, it did not meet target maturity for 12 of 21 attributes.

2.7 As defined in its 2025–26 PMP, Services Australia is aiming to improve its maturity to the rating of ‘leader’ across 13 attributes, sustaining its maturity of ‘defined’ across five attributes, and sustaining its maturity of ‘leader’ for three attributes. The decline in target completion from 2021–22 has reflected a change in target maturity levels and changes to self-assessment.

2.8 As Services Australia has noted in its 2025–26 PMP, it has a high-risk privacy profile due to it providing complex public services and handling a significant amount of personal information. Services Australia is aiming for higher levels of privacy maturity so that it has arrangements which are commensurate with this risk profile.

2.9 The attributes in the PMP are taken from those provided in the OAIC template. Services Australia’s uses these OAIC-provided attributes and adapts them to its own operational context, such as in the 2025–26 PMP where the OAIC-provided attribute of ‘Privacy Values’ is discussed by with specific reference to its internally-developed operational privacy policy.

2.10 Services Australia is required by subsection 9(3) of the APP Code to measure performance against the PMP at least annually. In accordance with this requirement, quarterly reporting of PMP activities has been provided to relevant executive officers within Services Australia and the Security Committee.

Privacy Officers and Privacy Champion

2.11 The APP Code requires an entity to have:

- a Privacy Officer to be the ‘primary point of contact for advice on privacy matters’ (section 10); and

- a Privacy Champion who is a senior official in the entity (section 11).

2.12 Services Australia has two Privacy Officers (General Counsel, Privacy and Personal Information Release branch and General Counsel, Digital Delivery and Privacy Legal branch) and a Privacy Champion (the Chief Counsel also has the role of Privacy Champion) whose roles are defined by those functions required by sections 10 and 11 of the APP Code.

2.13 The Privacy Officers are responsible for the management of privacy complaints and enquiries, maintaining a record of personal information holdings in the entity, overseeing the conduct of privacy impact assessments (chapter 3, from paragraph 3.19), and maintaining a register of these assessments.

2.14 The Privacy Champion promotes a positive privacy culture and privacy values, provides leadership on privacy matters, reviews and approves the PMPs, and advises and reports to Service Australia’s executive bodies on privacy issues.

2.15 In February 2023, Services Australia established the Privacy Contact Officer Network (PCON) to share information about privacy requirements and initiatives throughout the agency, and to ‘ensure the agency’s compliance with the Australia Privacy Principles’ (see case study 1).

|

Case study 1. Privacy Contact Officer Network (PCON) |

|

Services Australia established a pilot PCON in February 2023 to enhance privacy awareness across the agency, and to consolidate ‘privacy management practices throughout the agency by capitalising on shared skills, knowledge, and experience’. As of May 2025, PCON had 88 contact officers. Contact officers are Executive Level (EL) 1 or EL2 employees and are provided with additional education on Services Australia’s privacy processes, governance arrangements, and the legal obligations related to privacy. PCON acts as a community of practice, meeting monthly with the Privacy Officers and the Privacy Champion. Key activities include:

A 2023 evaluation of the PCON pilot found that it had ‘improved privacy awareness in the agency’ and had enhanced the capability of staff in managing privacy incidents and risks. |

Does Services Australia appropriately assess risks to the privacy of client information under its enterprise risk management framework?

Services Australia’s enterprise-level Risk Management Policy and Framework categorises privacy as a ‘specialist risk’. It does not have a privacy risk management plan or privacy specific enterprise risk or risk tolerance statement. Privacy related risks are incorporated in the group risk management plans of the seven service groups. There has been an increase in the volume of data breaches in Services Australia, largely caused by malicious actors. Third parties are not required to notify Services Australia following a data breach involving government identifiers, creating a risk to the timeliness of assessments of these breaches. Services Australia has not developed a technology security risk management plan as required by PSPF Direction 002-2024.

2.16 Section 16 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requires entities to establish and maintain appropriate systems and internal controls for the oversight and management of risk.

Enterprise risk management

2.17 Services Australia’s Risk Management Policy and Framework (RMPF) is ‘the set of components and arrangements that articulate the direction and approach for managing risk in the agency’. The October 2024 RMPF is aligned with the requirements of the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy and outlines the hierarchy of risk management arrangements and roles and responsibilities. As of October 2025, Services Australia has 10 enterprise risks, each led by a deputy Chief Executive Officer (CEO) in their role as risk stewards.22

2.18 None of the 10 enterprise risks explicitly refer to privacy. Enterprise risks 8 and 9 are related to privacy as these refer to risks to data, which in Services Australia is largely personal information.

Data: We fail to ensure the appropriate governance, curation, and use of data [enterprise risk 8].

Cybersecurity: We fail to detect and protect our systems and data holdings from internal or external malicious or unintentional activity [enterprise risk 9].

2.19 While Services Australia has not set a specific risk appetite statement or risk tolerances for privacy, its risk tolerance for privacy is referenced under the following themes from its RMPF: ‘security information and systems’ (low tolerance); and ‘fraud and integrity’ (medium tolerance, although low tolerance for unethical or illegal conduct).

Group risk management plans

2.20 Rather than having a single enterprise-level or agency-wide risk management plan, Services Australia’s seven service groups each identify group risks that could impact the delivery of group objectives and align these risks to the 10 enterprise risks. Deputy CEOs are responsible for managing enterprise risks through group risk plans, which inform the development of a ‘quarterly Enterprise Risk Profile’ for Executive Committee discussion and endorsement’.

2.21 Group risk management plans (GRMPs) are reviewed and approved by the relevant deputy CEO and individual group risks are administered by group risk owners.23 The GRMPs contain ‘aggregated risk information for the group’ and do not assess operational risks, which are ‘day-to-day risks [that] all staff are expected to identify, control and escalate’. They include a risk register, a risk rating summary, controls, and the risk decision by the risk owner, including notes to accept where a risk is outside of tolerance.

2.22 ANAO analysis of GRMPs for the first quarter of 2024–25 found that privacy-relevant risks were incorporated into the GRMPs of the seven service groups, and aligned primarily to enterprise risks 8 and enterprise risk 9 (see paragraph 2.18).

2.23 In quarter 1, 2024–25, four service groups covered privacy risks under group risks mapped to enterprise risk 8: Data, one group under enterprise risk 9: Cyber Security, and one group under both 8: Data and 9: Cyber Security, and one group under enterprise risk 1: Future Readiness. For example, the Corporate Enabling Group had the following privacy relevant group risk linked to enterprise risk 8: Data:

The workforce and systems do not protect sensitive personal, personnel, financial and government, data and information (and customer data where the group is responsible).

2.24 Services Australia has developed the Agency Control Library (ACL) to document the suite of 252 controls available to mitigate the range of group risks.24 ANAO analysis of the quarter 1, 2024–25 GRMPs identified 11 privacy-specific ACL controls related to privacy governance and policies, privacy education and training, information release and exchange, scams and identity theft. Privacy-related ACL controls targeted the specialist risks of fraud and corruption, cyber and data security.

2.25 The GRMPs map ACL controls to risk causes and consequences. Controls to mitigate privacy risks and the risk causes and consequences are aligned. For example, the quarter 1, 2024–25 GRMP of the Corporate Enabling Group contains the privacy-relevant risk cause:

Inappropriate handling (collection /storage / transmission / disposal) of sensitive data and information, including personal and protected information.

2.26 Controls to mitigate this risk include the operational privacy policy; information security policy and procedures; the protective security plan 2023–25; protective security incident management; and security classifications and dissemination limiting markers.

Specialist risks

2.27 Services Australia has ‘specialist’ risk areas to ‘provide agency-wide direction on risks’ and ‘report independently through relevant committees’. In the October 2024 RMPF, there were 11 specialist risk areas, including for legal, financial, fraud, security, cyber security and privacy. While the RMPF does not define the term ‘specialist risk’, it states that:

- Under the direction of their Deputy CEOs, specialist risk areas … assist to strengthen, integrate and support specialist risks, providing direction to agency officials on the management of their risk discipline in line with relevant Commonwealth legislation and policies.

- These areas monitor and report on the impact of their risk discipline on the agency to their line management and relevant enterprise governance committees.

2.28 Services Australia has risk management plans for the specialist risks of fraud and corruption, and security. These incorporate privacy risks.

- The Fraud and Corruption Control Plan 2025–2026 explains Services Australia’s approach to managing privacy and related legal obligations and summarises strategic alignment with privacy-related strategies and plans.

- The Protective Security Plan 2023–25 explains governance arrangements for privacy and related legal obligations and lists security requirements and actions relevant to privacy.

2.29 Services Australia does not have a separate privacy risk management plan. Paragraph 2.32 outlines the benefits that such a plan could provide.

Privacy management plan — risk identification and assessment

2.30 Services Australia self-assessed its performance against the attribute of ‘privacy risk identification and assessment’ in its 2024–25 PMP as ‘defined’ (see paragraph 2.3), meaning that ‘Strong, clear and consistent processes exist for identifying and assessing privacy risks’ and that privacy risks have been ‘integrated into agency’s wider risk management framework’.

2.31 In this self-assessment, Services Australia outlined that it operates a ‘three lines of defence’ model with ‘strong privacy officer involvement’ — these measures are defined as:

First line — operational privacy risks are identified and recorded in risk register and control activities are documented.

Second line — the Privacy Officer collaborates with information security, data governance and risk functions to provide oversight of privacy risk management.

Third line — internal audit (or independent assessors) conduct regular privacy-related assurance activities.

2.32 Despite being categorised as a ‘specialist’ risk, Services Australia does not have an enterprise-wide risk management plan for privacy (a privacy risk management plan). A privacy risk management plan could:

- underpin the first line of defence described above;

- complement the annual review and development of PMPs;

- assist with the identification, assessment and management of privacy risks across the seven service groups;

- provide an enterprise-wide view on privacy risk tolerances at a more specific level; and

- assist to better manage the potential harm to individuals resulting from privacy breaches.

2.33 Establishing these risk management arrangements at the enterprise-level for privacy would better reflect that Services Australia has a high-risk profile for privacy.

Recommendation no.1

2.34 Services Australia improve the identification, assessment and management of privacy risks by implementing an enterprise-wide privacy risk management plan.

Services Australia response: Agreed in principle.

2.35 The Agency agrees in principle with this recommendation and will explore opportunities to improve the identification, assessment and management of privacy risk. Effective management of privacy risk is critically important to the Agency as part of our commitment to building public trust.

2.36 The Agency’s risk management policy and framework establishes that all risks, including privacy risks, are managed within group risk management plans that are overseen by deputy CEOs. This means that risks are assessed, accepted, treated, monitored and reported alongside other risks using a consistent methodology. This approach also ensures accountability for acceptance, assessment, treatment and monitoring of risk resides within the operational areas best placed to manage those risks.

2.37 The Agency’s Executive Committee provides oversight and guidance for each of the Agency’s 10 enterprise risks which cover elements of privacy risk.

2.38 The recommendation currently prescribes only one solution to improving the identification, assessment and management of privacy risks, through the introduction of a standalone enterprise-wide risk management plan.

2.39 The Agency will address the intent of the recommendation through a targeted and integrated approach in alignment with the current risk management policy and framework. This will include:

- improving how privacy risks are embedded into group risk management plans;

- stronger emphasis and integration of privacy risks into the Agency’s enterprise risk framework;

- enhancing the reporting and visibility of privacy risk trends to the Security and Audit and Risk Committees; and

- aligning privacy risk oversight with existing documents, such as the Privacy Management Plan.

Reporting and review

2.40 Services Australia’s Executive Committee, chaired by the CEO, receives quarterly risk reports on enterprise risks. Reports focus on enterprise-risks that exceed levels of risk tolerance (see from paragraph 2.118 for reporting and monitoring arrangements).

2.41 The Chief Counsel provides updates to Services Australia’s audit and risk committee on privacy matters, such as notifiable data breaches.

2.42 Services Australia advised the ANAO on 29 January 2025 that:

The Chief Operating Officer gives a weekly operational briefing on [Notifiable Data Breaches] and privacy incidents to the CEO and Agency Executive through Executive Stand-Up. Specific incidents are escalated for visibility of key senior executives, in accordance with the Privacy Incident and Data Breach Response plan.

Management of specific privacy risks

Privacy risks arising from technology risks

2.43 Vulnerabilities in information management and computer systems present interrelated risks to the privacy of individuals and fraud and corruption and may be exploited for malicious purposes which could impact individuals as well as entities. The Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) Direction 002-2024 requires entities ‘to identify and actively manage the risks associated with vulnerable technologies they manage, including those they manage for other entities’.25

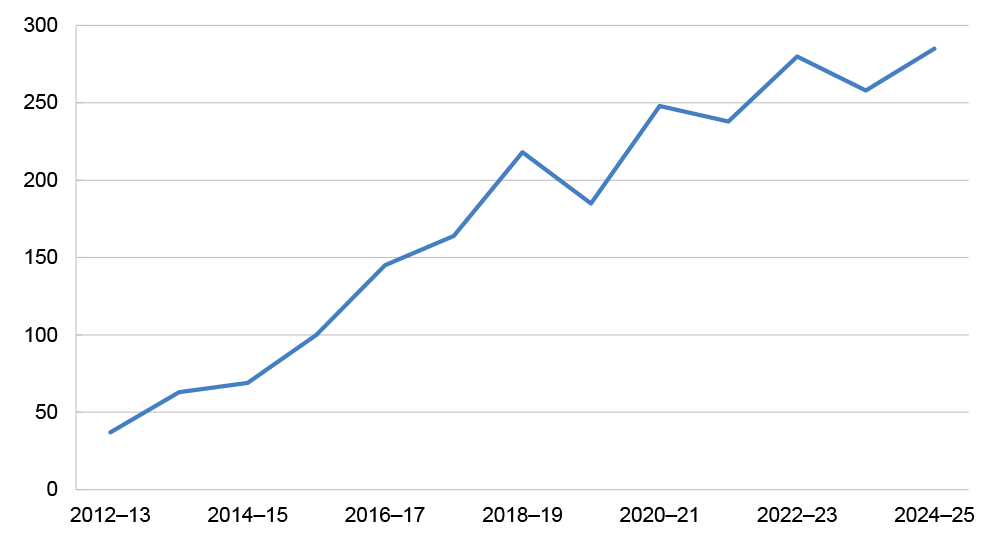

2.44 Services Australia relies on ‘multiple ageing legacy ICT systems to deliver services and payment’, which creates risks to privacy. PSPF Direction 002-2024 urges Australian Government entities to ‘proactively seek out vulnerabilities that may be present on Australian Government networks’.26 The number of notifiable data breaches (NDBs) (see paragraph 3.50) attributed to malicious or criminal attacks on Services Australia systems or client access credentials has increased from three in 2019–20 to 82 in 2024–25. Services Australia advised the ANAO in November 2025 that these NDBs primarily involve incidents where customers have inadvertently provided personal information and myGov sign-in credentials to parties impersonating the agency.

2.45 Services Australia’s Protective Security Plan 2023–25 outlines the protective security environment, including high level risks, governance and responsibilities. Services Australia had not developed a technology security risk management plan27 by 30 June 2025, as required by PSPF Direction 002-2024. Services Australia produced a technology asset stocktake, as required by that direction. It advised the ANAO on 6 November 2025 that it planned to provide a draft technology security risk management plan for approval to its Security Committee in December 2025.

Privacy risks arising from third-party data breaches

2.46 APP 9 covers the adoption, use and disclosure of ‘government related identifiers’, such as Medicare numbers and Centrelink reference numbers, by third-party organisations.

2.47 In 2022, Services Australia developed a third-party compromise response plan (TPCRP) in response to data breaches (Optus28, Medibank29, and Medlab30) that involved government-related identifiers. The TPCRP describes Services Australia’s approach to monitoring, assessing, and responding to third-party compromises to prevent and mitigate fraud against the agency and its clients, resulting from the compromise of sensitive information held by an external third party. It outlines the roles and responsibilities for managing the response to a third-party compromise, including determining what credentials have been exposed and the information impacted. The TPCRP was updated on 15 August 2024. It is not identified as a control in the Agency Control Library.

2.48 Two groups within Services Australia (the Technology and Digital Program Group and the Payments Integrity Group) include third-party data breaches as causes of group risks in their GRMPs. Services Australia advised the ANAO on 4 April 2025 that it becomes aware of third-party compromises through the OAIC and the Australian Cyber Security Centre, media monitoring, or advice from affected individuals.

2.49 The TPCRP states that Services Australia ‘does not have legislated authority to compel third parties to share information about a data breach or compromise event where agency issued credentials are impacted’ and instead ‘seeks and obtains information from third parties in compliance with section 86E of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth)’, and under guidance from the Crimes Legislation Amendments (Powers, Offences and Other Measures) Act 2018 (Cth), which states that ‘a release of information for ‘integrity purposes’ is permissible under Australian Privacy Principle 6 in the Privacy Act 1988’.

2.50 Requests for voluntary provision of information from third parties occur when there has been exposure of ‘agency issued credentials’ such as Medicare details or Centrelink customer numbers and ‘personally identifiable information’ that could enable a malicious actor to impersonate a genuine customer, make false claims or redirect payments.

2.51 In contrast, third-party compromises relating to My Health Records must be notified to the OAIC and the system operator, which is the Australian Digital Health Agency, as outlined in the OAIC’s Guide to mandatory data breach notification in the My Health Record system.31 The OAIC’s data breach action plan for health service providers states ‘you may wish to contact Services Australia [link to external site] to discuss options for protecting customers’ Medicare, Centrelink or Child Support records’.32

2.52 With multiple notifiable data breaches relating to ‘government related identifiers’ issued by Services Australia since 2022, there is a risk that the personal information of Services Australia’s clients could be further compromised before Services Australia is notified and undertakes a risk assessment. Services Australia does not have formalised arrangements with external entities or parties to facilitate the notification of such breaches. This creates a risk that Services Australia may not be made aware of such breaches in a timely manner, meaning that it may not be able to respond in a timely manner to personal information compromises.

Recommendation no.2

2.53 The Australian Government consider implementing arrangements to support Services Australia being provided with timely notification of third-party data breaches involving government-related identifiers such as Medicare numbers and Centrelink reference numbers.

Attorney-General’s Department response: Agreed.

2.54 The Attorney-General’s Department (the department) notes the importance of ensuring that government-related identifiers are appropriately protected in accordance with APP 9, and of taking timely steps to mitigate the risk to Australians when those identifiers are potentially disclosed through a data breach. The department is developing a second tranche of privacy reforms for consideration by the Government, including consideration of reforms to the Notifiable Data Breaches scheme. Alongside that work, the department will give consideration to possible arrangements to facilitate timely notification to Services Australia when a regulated entity has experienced a data breach involving government-related identifiers. Similar to the approach in the My Health Record system, the most appropriate arrangements may be through OAIC guidance, rather than legislative amendment. The department will consult the OAIC in undertaking this work.

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner response: Agreed.

2.55 The OAIC would support a requirement for entities to notify Services Australia directly following a relevant data breach, however mandating such a requirement would be a matter for Government.

2.56 Services Australia supports clients affected by third-party data breaches by providing advice regarding the protection of agency-issued credentials.33 The TPCRP outlines the following.

- The responsibility to notify individuals affected by a breach lies with the third party that incurred the breach, and notification should be done in accordance with OAIC guidelines and the Privacy Act. Services Australia considers communicating with impacted individuals on a case-by-case basis, depending on additional risks due to vulnerabilities.

- Services Australia’s response to a third-party data breach can include: applying protective measures to impacted client accounts and monitoring of accounts for suspicious or fraudulent activities; requesting password resets for, and providing email notifications in, MyGov accounts; public messaging on Services Australia’s website; and undertaking data-matching activities for certain types of breaches (see paragraph 2.58).

2.57 Services Australia undertakes ‘data matching activities for third-party organisation data breaches’ to assess and manage the risk of client identity theft and fraud. This type of data matching involves comparing Services Australia’s Medicare and Centrelink client records with information from a third-party organisation to identify affected clients.

2.58 As of June 2025, Services Australia has published 14 data-matching program protocols for third-party data breaches (developed between 2022 and February 2024) for data-matching activities that involve over 5,000 individuals. The protocols are published on Services Australia’s website34 and in the Australian Government Gazettes35 as recommended in the OAIC’s voluntary Guidelines on data matching in Australian Government administration (voluntary data matching guidelines) (refer to paragraph 2.93).

Has Services Australia developed appropriate policies to manage the privacy of client information consistent with the Privacy Act 1988?

Services Australia publishes a privacy policy and privacy notices that largely comply with the requirements of Australian Privacy Principles 1 and 5. Services Australia does not regularly review its public privacy policy and privacy notices. Review of these products would benefit from client input. Services Australia maintains an internal operational privacy policy and ‘operational blueprints’ that provide guidance to staff. The operational privacy policy was reviewed in 2023–24. Services Australia has policies to support individuals access their own information, and to support appropriate data destruction.

Public privacy policy and privacy notices

2.59 The Privacy Act sets out the requirements for a privacy policy under APP 1 and privacy notices under APP 5. The Australian Privacy Principles Guidelines provide entities with further guidance.36

- Under APP 1, an entity must have a clearly expressed and up-to-date policy about the management of personal information by the entity. It must be readily available.

- Under APP 5, an entity must take steps to notify individuals about the collection of their personal information.

2.60 Services Australia publishes a privacy policy37 on its website, which links to other privacy content including 19 program-specific privacy notices and other documents, such as:

- Child Care Subsidy privacy notice for customers;

- Child Care Personnel and Provider Digital Access (PRODA) privacy notice;

- COVID-19 and influenza (flu) immunisation history statement privacy notice;

- National Redress Scheme privacy notice;

- Centrelink data-matching activities (see from paragraph 2.79);

- Data-matching activities for third-party organisation data breaches (see from paragraph 2.46); and

- CCTV privacy notice.

2.61 Services Australia also includes privacy notices:

- within Services Australia’s client forms used for payment applications38;

- on the myGov website; and

- in scripts used by officers during inbound and outbound calls.

2.62 Services Australia’s privacy policy satisfies the requirements of APP 1 and privacy notices largely meet the requirements of APP 5, with the exception that not all data-matching programs have been published (see paragraphs 2.96 and 2.97). Privacy notices are updated by individual policy and program owners. Services Australia does not coordinate the review of its privacy notices and privacy policy at an enterprise level. Services Australia does not test the format or content of privacy information with clients, as recommended by the OAIC’s Guide to developing an APP privacy policy.

Opportunity for improvement

2.63 Services Australia could engage clients to inform regular reviews of its privacy policy and privacy notices to ensure that information in presented in formats that meet client needs.

Operational privacy policy and operational blueprints

2.64 Services Australia maintains an internal operational privacy policy and privacy-related operational blueprints that provide specific guidance to staff.

2.65 The operational privacy policy was first approved in 2018. It was updated in December 2024, with the next review due in December 2025. The purpose of the policy is ‘to ensure staff manage personal information of customers and staff in accordance with the agency’s obligations under the Privacy Act, and the Privacy Code [the APP Code]’. The policy sets out that all staff are responsible for:

- understanding the obligations that apply to them, including how to manage personal information and potential consequences from breaches of the Privacy Act;

- promoting privacy awareness and compliance, including awareness of the Privacy Officers and Privacy Champion;

- completing mandatory privacy training, reporting and managing a privacy incident, providing guidance on privacy management processes such as privacy threshold and impact assessments; and

- understanding and adhering to this policy.

2.66 As of June 2025, Services Australia has over 5,000 operational blueprints that outline procedures for staff performing various functions. The ANAO identified 39 operational blueprints that provide privacy guidance. The ANAO assessed a sample of 28 operational blueprints (including 12 privacy specific) and found that these provide largely appropriate guidance to staff, with the exception that the privacy blueprints did not always include references to relevant legislation, OAIC guidance and Services Australia’s privacy policies.

Opportunity for improvement

2.67 Services Australia could improve its privacy operational blueprints with the inclusion of references to privacy legislation, privacy policy and OAIC guidance.

Access to personal information

2.68 APP 6 requires that entities must not disclose personal information for a secondary purpose unless an individual has consented. APP 12 sets out requirements for entities to provide individuals with access to their own information.

2.69 Services Australia has policies and processes in place to manage client and third-party requests for information about clients, including requests by individuals, through freedom of information (FOI), by consent, public interest requests and by subpoena.39

Individuals’ requests for personal information

2.70 Individuals can access their personal information through myGov, by request to Services Australia or through a freedom of information (FOI) request. Individuals can also consent to third parties requesting their information from Services Australia on their behalf40, including through the Customer Information Release Service.41 Consent requests are processed by a personal information release team who undertakes authorisation verifications in accordance with APP 6. In 2024–25, Services Australia received 45,056 requests for information by consent.

Freedom of information requests for personal information

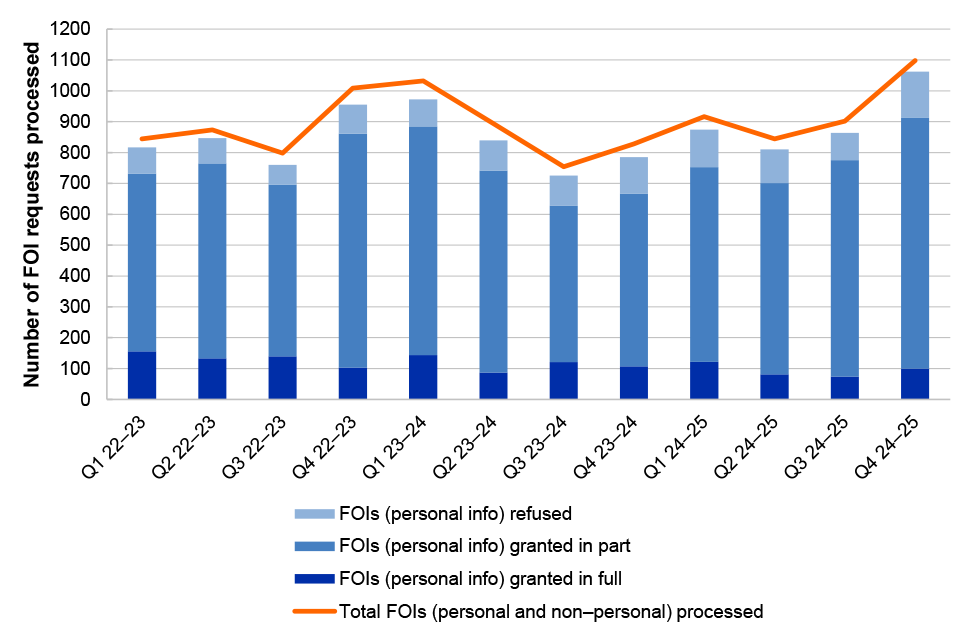

2.71 Services Australia received 4,469 FOI requests for personal information in 2023–24, and 4,899 requests in 2024–25. In a submission to the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs made in October 2025, Services Australia noted that approximately 95 per cent of all FOI requests it receives are for access to personal information.42 See Appendix 2 for discussion on how Services Australia reported these figures to the OAIC.

2.72 In processing these FOIs for personal information, Services Australia can release the information in full, in part, or refuse to release any information. Most FOI requests which Services Australia receives are for the release of personal information — 94 per cent of all FOI requests in 2023–24, and 95 per cent in 2024–25 (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2: Services Australia FOI request processing, 2022–23 to 2024–25

Source: ANAO analysis of Services Australia FOI request processing data, as reported to the OAIC.

Australian Government freedom of information statistics, 13 January 2025, available from https://www.oaic.gov.au/freedom-of-information/australian-government-freedom-of-information-statistics.

Public interest requests for information and subpoenas

2.73 In some cases, requests for an individual’s information may come from a third party who is not acting on behalf of an individual under their authorisation. Services Australia has processes in place to respond to requests to release information requested under public interest grounds and to respond to subpoenas.

2.74 The Social Security (Public Interest Certificate Guidelines) (DSS) Determination 2015 permits Services Australia to issue Public Interest Certificate ss to support the release of information to third parties under paragraph 208(1)(a) of the Social Security (Administration) Act 1999.43 This provides for the release of information to police, coroners, state government agencies and other parties for relevant purposes, such as law enforcement, confirmation of housing and educational statuses, child protection matters, and for supporting or investigating the health and welfare of an individual (such as missing persons).

2.75 Services Australia received 23,241 public interest requests for information in 2024–25, and 22,289 in 2023–24. In 2024–25, the largest volume of requests (10,357) were made by police and other law enforcement agencies (for criminal matters and missing persons), followed by 7,753 from government agencies acting on child protection matters, and 2,474 medical related requests (including 1,819 from the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency).

2.76 Services Australia was issued 7,014 subpoenas for personal information in 2024–25. Services Australia advised the ANAO on 19 March 2025 that its processes for managing subpoenas involves ensuring their legitimacy and authority through the courts, and that if Centrelink information has been requested that it is only released if relevant to section 207 of the Social Security Act 1991.

Data destruction and disposal

2.77 Services Australia has designated its records management team as responsible for the disposal of records with business areas as needed. To support these activities, and compliance with its obligations under APP 11 (security of personal information), Services Australia has developed four program-specific Records Authorities with the National Archives of Australia to govern the destruction and disposal of data used in support of programs.44

2.78 The four Records Authorities operate alongside the Administrative Functions Disposal Authority (AFDA) to guide Services Australia on its obligations as to how and when records pertaining to its service delivery activities can be disposed of.45 This includes for core service delivery functions, payment and service delivery management functions, specific Medicare functions, and specific Child Support functions.

Do Services Australia’s data-matching activities comply with legislation and guidelines?

Services Australia no longer undertakes data matching under the Data-matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Act 1990 and instead follows the voluntary guidelines on data matching in Australian Government administration. This approach reduces transparency and accountability to Parliament. There was no documented rationale or legal advice to underpin this change. Services Australia has not fully implemented Robodebt Royal Commission recommendations relating to data matching. Services Australia has published 13 of 32 data-matching protocols.

2.79 Data matching ‘means the bringing together of at least two data sets that contain personal information, and that come from different sources, and the comparison of those data sets with the intention of producing a match’.46

2.80 Entities that carry out data matching must comply with the Privacy Act. The OAIC sets out two frameworks for government data matching.

- Data matching involving tax file numbers (TFNs) to detect incorrect payments is governed by the Data-matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Act 1990 (the DMP Act) and the Data-matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Rules 2021 (data matching rules)47 — see from paragraph 2.83.

- Data matching for other purposes is done under the OAIC’s 2014 voluntary Guidelines on data matching in Australian Government administration (voluntary data-matching guidelines)48 — see from paragraph 2.93.

2.81 Further requirements are set out in the Privacy (Tax File Number) Rule 2015, issued by the Privacy Commissioner under section 17 of the Privacy Act, which states that:

the Data-matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Act 1990 provides for, and regulates, the matching of records between the Australian Taxation Office and assistance agencies using the TFN in part of the matching process.49

2.82 Additional requirements for data matching involving Medicare and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) data are set out in the National Health Act 1953 and the National Health (Privacy) Rules 2025.50

Data matching under the Data-matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Act 1990

2.83 The DMP Act prescribes how data matching of TFNs is to occur.

- Matching is undertaken by a matching agency (Services Australia) (section 4).

- It specifies application to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) as well to ‘assistance agencies’ defined as the Education Department, the Social Services Department, the Veterans’ Affairs Department and Services Australia (subsection 3(1)).51

- There are to be no more than nine data matching cycles in a year (subsection 6(1)(2)).

- Requires entities to report annually to Parliament through the OAIC on the conduct of data matching activities (subsection 12(4)).

- Requires entities to report to Parliament through their responsible Minister every three years ‘including all the details relating to the data-matching program carried out during the period’ that are specified in the data matching rules (subsection 12(5)).

2.84 Services Australia reported on its DMP Act data matching in its annual report until 2015–16. In its 2016–17 Annual Report, Services Australia stated that it was no longer operating under the DMP Act52, and that it had commenced data matching under the OAIC voluntary Guidelines on data-matching in Australian Government administration (voluntary data-matching guidelines).

2.85 The voluntary data-matching guidelines ‘assist Australian Government agencies to use data matching as an administrative tool in a way that complies with the APPs and the Privacy Act, and is consistent with good privacy practice’. The voluntary data matching guidelines state that:

The Guidelines do not generally apply to data matching where Tax File Numbers are used. The Data-matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Act 1990 (Cth) regulates the use of Tax File Numbers in comparing personal information held by the Australian Taxation Office and by certain ’assistance agencies’.53

2.86 Services Australia continues to undertake data matching involving TFNs for child support payments and income data, including for example, ‘near-real-time’ single touch payroll (STP) data, where:

The ATO conducts an identity matching exercise to determine the relevant STP records to send to the Agency. ATO does this by matching the personal information provided by the Agency with the records of the ATO. Personal information includes Centrelink Customer Reference Numbers (CRN) or Tax File Number (TFN) for Child Support customers. The ATO replies to the Agency by providing STP data reported by the employers, for mutual customers.54

2.87 The Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme (Robodebt Royal Commission) provided insight into the data-matching activities undertaken by Services Australia, and provided recommendations relevant to the legal management of these activities. The Information Commissioner’s evidence to the Robodebt Royal Commission stated: