Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

2024–25 Major Projects Report

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Report snapshot

Purpose of the MPR

- The Major Projects Report (MPR) is an annual review of a selection of the Department of Defence’s (Defence) major equipment acquisition projects. The 2024–25 MPR is the 18th in the series. The MPR is undertaken at the request of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) and informs parliamentary scrutiny and the national conversation on major Defence acquisitions.

Key facts

- In 2024–25, the 21 projects in the MPR were valued at $81.5 billion and represented 32 per cent of total Defence acquisition budget.

- As at 30 June 2025, the total expenditure of projects in the MPR was $37 billion.

- Two projects in the MPR were listed as a Project of Concern and seven projects were listed as a Project of Interest.

- The projects in the 2024–25 MPR cover seven of the 13 capability elements in the 2024 Integrated Investment Program.

What did we find?

- The Auditor-General concluded nothing came to her attention that caused her to believe the information reviewed in the Project Data Summary Sheets was not prepared in accordance with the 2024–25 MPR Guidelines.

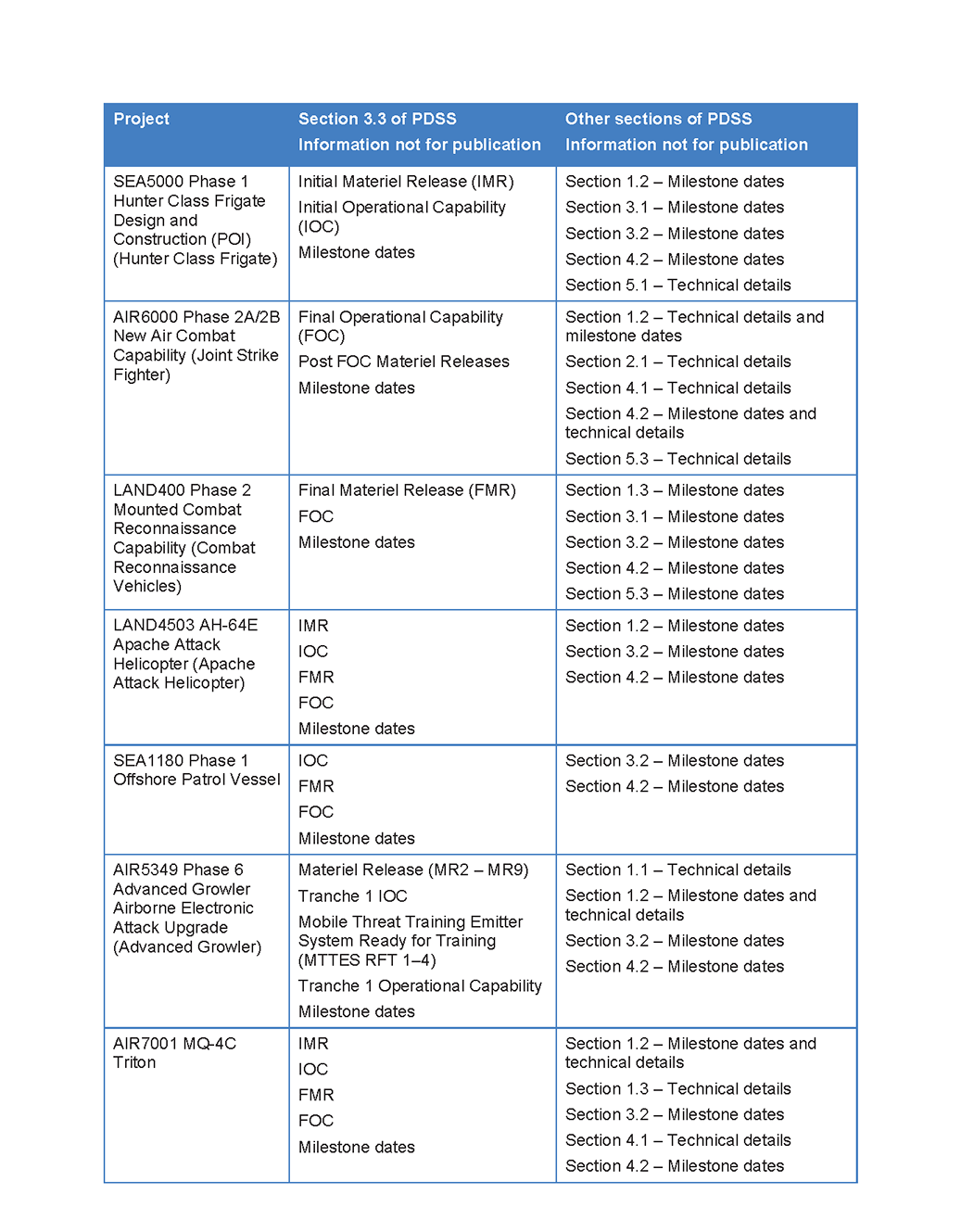

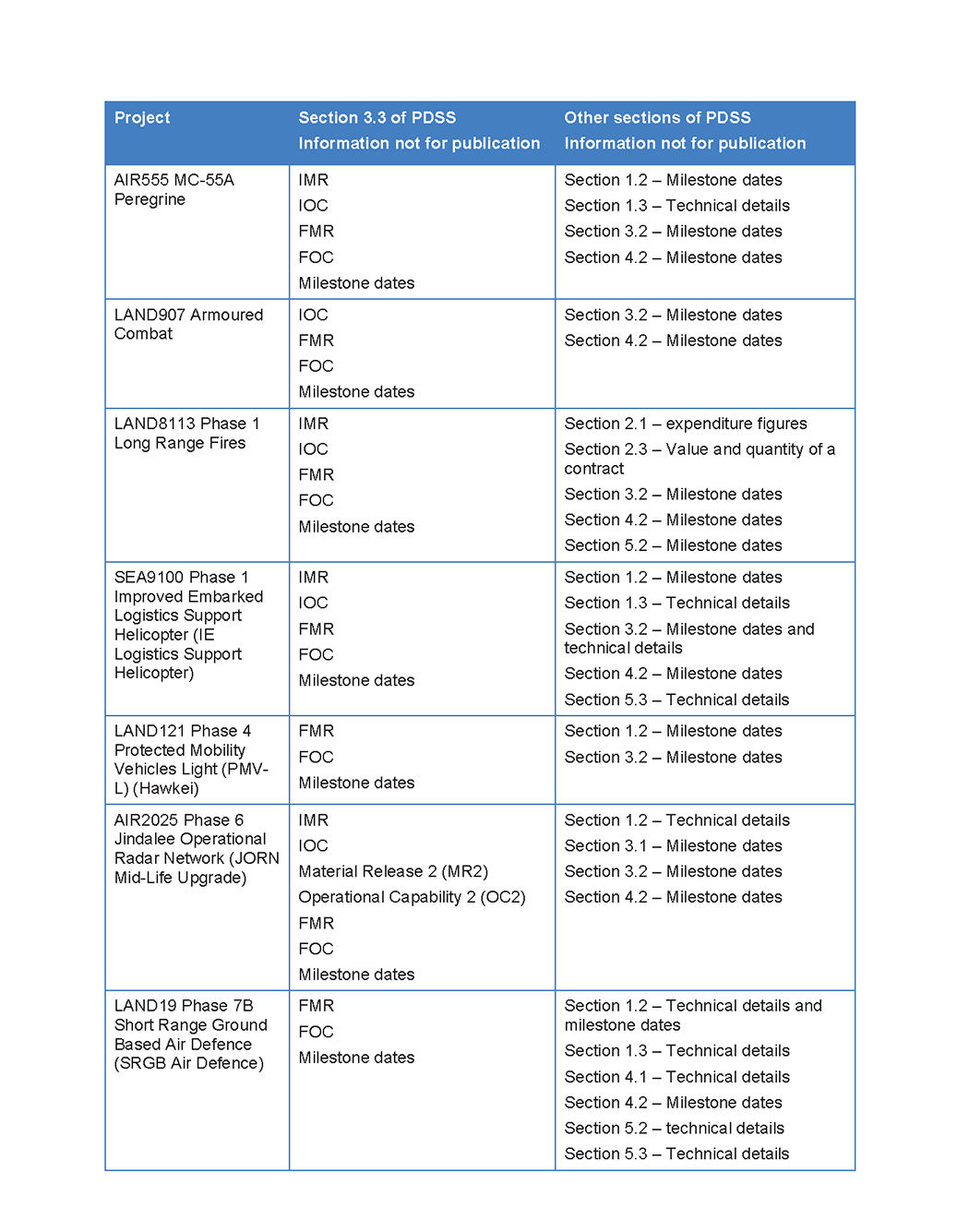

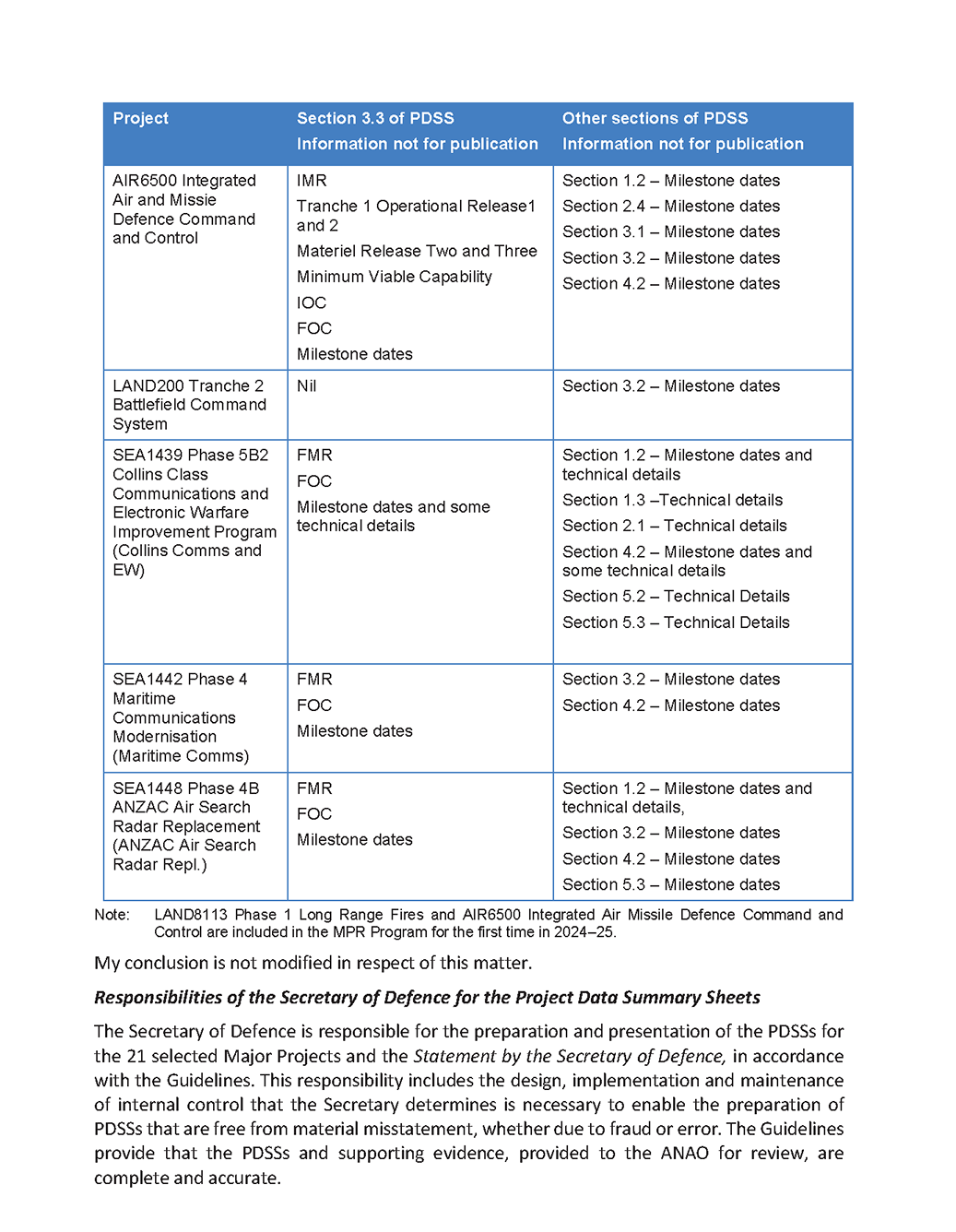

- There was one emphasis of matter regarding the level of information classified as ‘not for publication’ (NFP) in the PDSSs. Of the 21 projects, 19 PDSSs contained information marked NFP.

- Defence introduced Minimum Viable Capability (MVC) as a new milestone for one project, which had yet to determine dates for Initial Operational Capability (IOC) or Final Operational Capability (FOC).

- There were 108 risks and issues across the 21 projects, of which 50 were downgraded or retired and will be removed in 2025–26 MPR.

- The average slippage across each project is around two years.

1 of 21

projects disclosed that it would have insufficient funds to deliver the project to agreed scope.

8 of 21

projects have no total schedule slippage.

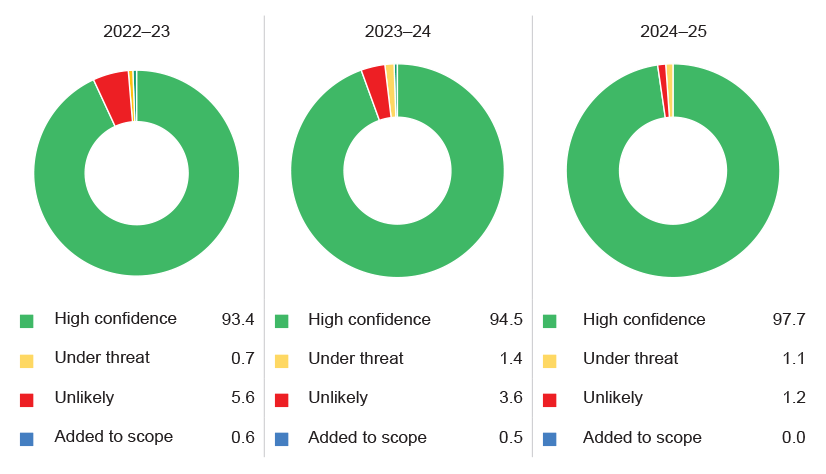

97.7%

was the expected delivery against project scope across the 21 projects (an increase of 3.2 per cent from 2023–24).

Due to the complexity of material and the multiple sources of information for the 2024–25 Major Projects Report, we are unable to represent the entire document in HTML. You can download the full report in PDF or view selected sections in HTML below. PDF files for individual Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSS) are also available for download.

!Part 1. ANAO Review and Analysis

1. Background

Introduction

The 2024–25 MPR is the 18th in the series and has reviewed a total of 63 major projects since its inception in 2008–09.

1.1 In the early 2000s, parliamentary interest in Defence acquisition projects was high. In 2003, the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Reference Committee found that there was poor visibility on the progress of major projects. The Committee recommended that the Senate request the Auditor-General to produce an annual report on the progress of major Defence projects.1

1.2 In 2006, the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) recommended that the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) produce an annual report based on data supplied by Defence on the progress of the top 30 capital equipment projects. The first report published in 2008–09 covered nine major projects, with the intention of reporting up to 30 in subsequent years.2 The 2024–25 Major Projects Report is the 18th edition in the series, which has now reviewed 63 major projects since its inception.

1.3 The Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) manages the introduction and development of new specialist military equipment for the Australian Defence Force (ADF), while the Naval Shipbuilding and Sustainment Group (NSSG) has been responsible for maritime capabilities since October 2022.

1.4 The 2024–25 Major Projects Report (MPR) contains Defence data and commentary on a selection of 21 of its major specialist military equipment acquisition projects, and a Project Data Summary Sheet (PDSS) for each project. Alongside this is an independent assurance and analysis by ANAO on key areas such as cost performance, schedule performance and capability/scope delivery.

Selected projects

The 2024–25 MPR covers 21 major projects representing $81.5 billion in approved budget — 16 of which are managed by CASG and five by NSSG.

1.5 The 21 projects in the 2024–25 MPR were selected based on criteria endorsed by the JCPAA through the 2024–25 MPR Guidelines. This represents approximately $81.5 billion in approved budget and accounted for 32 per cent of the total Defence acquisition budget. Of all projects managed by CASG and NSSG, the projects in the 2024–25 MPR represent 51 per cent of their total budget.

1.6 Table 1.1 outlines the 21 projects selected for review and their government-approved budgets as at 30 June 2025, listed in order of approved budget.

Table 1.1: 2024–25 MPR — selected projects and approved budgets as at 30 June 2025

|

Project number |

Project name |

Project abbreviation |

Acquisition categorya |

ACAT ratingb |

Approved budget ($m) |

|

SEA5000h |

Hunter Class Frigate Design and Construction |

Hunter Class Frigate |

Other |

I |

26,055.3 |

|

AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B |

New Air Combat Capability |

Joint Strike Fighter |

GtG |

I |

16,708.1 |

|

LAND400 Phase 2 |

Mounted Combat Reconnaissance Capability |

Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles |

Other |

I |

5,775.6 |

|

LAND4503 |

AH-64E Apache Attack Helicopter |

Apache Attack Helicopterc |

FMS |

II |

4,685.0 |

|

SEA1180 Phase 1h |

Offshore Patrol Vessel |

Offshore Patrol Vessel |

Other |

II |

3,707.4 |

|

AIR5349 Phase 6 |

Advanced Growler - Airborne Electronic Attack Upgrade |

Advanced Growler |

GtG |

II |

3,287.0 |

|

AIR7001 |

MQ-4C Triton |

MQ-4C Tritond |

GtG |

II |

2,444.3 |

|

AIR555 |

MC-55A Peregrine |

MC-55A Peregrinee |

FMS |

II |

2,399.4 |

|

LAND907 |

Armoured Combat |

Armoured Combatf |

FMS |

II |

2,388.4 |

|

LAND8113 Phase 1 |

Long Range Fires |

Long Range Fires |

FMS |

II |

2,388.5 |

|

SEA9100 Phase 1 |

Improved Embarked Logistics Support Helicopter |

IE Logistics Support Helicopter |

FMS |

III |

2,086.1 |

|

LAND121 Phase 4 |

Protected Mobility Vehicle – Light (PMV-L) |

Hawkei |

Other |

I |

1,975.5 |

|

AIR2025 Phase 6 |

Jindalee Operational Radar Network |

JORN Mid-Life Upgrade |

Other |

II |

1,250.4 |

|

LAND19 Phase 7B |

Short Range Ground Based Air Defence |

SRGB Air Defence |

Other |

II |

1,245.7 |

|

AIR6500 |

Integrated Air and Missile Defence Command and Control |

IAMD Command and Controlg |

Other |

I |

1,097.2 |

|

AIR5431 Phase 3 |

Civil Military Air Traffic Management System |

CMATS |

Other |

I |

1,010.9 |

|

LAND200 Tranche 2 |

Battlefield Command System |

Battlefield Command System |

Other |

I |

972.7 |

|

SEA1439 Phase 5B2h |

Collins Class Communications and Electronic Warfare Improvement Program |

Collins Comms and EW |

Other |

II |

617.8 |

|

SEA3036 Phase 1h |

Pacific Patrol Boat Replacement |

Pacific Patrol Boat Repl |

Other |

II |

568.5 |

|

SEA1442 Phase 4 |

Maritime Communications Modernisation |

Maritime Comms |

Other |

II |

443.2 |

|

SEA1448 Phase 4Bh |

ANZAC Air Search Radar Replacement |

ANZAC Air Search Radar Repl |

Other |

II |

429.5 |

|

Total (21 projects) |

81,536.5 |

||||

Note a: For the purposes of the analysis of this report, the ANAO has categorised projects based on their lead contract or primary acquisition arrangement. Foreign Military Sale (FMS) is an agreement between the US Government and a foreign government. The government-to-government (GtG) category is where the Australian Government and a foreign government enter into an arrangement, including co-operative agreements. ‘Other’ approaches typically involve direct contracts with commercial suppliers.

Note b: Defence assigns the Acquisition Categorisation (ACAT) level by project acquisition complexity in four levels of descending risk, from ACAT I, which is characterised by very high levels of complexity and technical risk, to ACAT IV, which has the lowest levels of complexity. The complexity of a project may vary over its life cycle.

Note c: In the 2024–25 MPR Guidelines, this project was titled LAND4503 Phase 1 Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter (ARH) Replacement (ARH Replacement).

Note d: In the 2024–25 MPR Guidelines, this project was titled AIR7000 Phase 1B MQ-4C Triton Remotely Piloted Aircraft System (MQ-4C Triton).

Note e: In the 2024–25 MPR Guidelines, this project was titled AIR555 Phase 1 Airborne Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance and Electronic Warfare (ISREW) Capability (Peregrine).

Note f: In the 2024–25 MPR Guidelines, this project was titled LAND907 Phase 2/LAND8160 Phase 1 Main Battle Tank Upgrade, Combat Engineering Vehicles (Heavy Armoured Capability).

Note g: In the 2024–25 MPR Guidelines, this project was titled AIR6500 Phase 1 Joint Air Battle Management System (JABMS).

Note h: These projects are managed by NSSG, all other projects are managed by CASG.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2024–25 PDSSs.

National Defence Strategy and Integrated Investment Program

The projects in the 2024–25 MPR cover seven of the 13 capability elements outlined in the 2024 Integrated Investment Program.

1.7 The 2023 Defence Strategic Review3 recommended a strategic update be released every two years through a National Defence Strategy.4 The inaugural 2024 National Defence Strategy (NDS) provides a new approach to addressing Australia’s most significant strategic risks through a more integrated, focused Defence force. The NDS sets out six key capability effects that Defence needs to deliver in order to achieve this objective.5

1.8 The 2024 Integrated Investment Program (IIP) sets out 13 specific capabilities the Government will invest in to deliver an integrated, focused force across its five capability domains to give effect to the NDS.6 Defence’s five capability domains are maritime, land, air, space and cyber and the 2024–25 MPR covers the maritime (sea), land and air domains. Future iterations of the MPR may need to consider the additional domains of space and cyber.

1.9 Table 1.2 provides the ANAO’s assessment of coverage across the 2024–25 MPR and the investment priorities of the 2024 IIP.

Table 1.2: Coverage of Defence acquisitions in the 2024–25 MPR when compared with the 2024 IIP capability investment priorities

|

Capability element in the 2024 IIP |

ANAO assessment of MPR coverage |

2024–25 MPR projects |

Total MPR project budget ($m)a |

|

Undersea warfare |

◔ |

SEA1439 |

617.8 |

|

Maritime capabilities for sea denial and localised sea control operations |

◑ |

SEA5000, SEA1180, SEA3036, SEA9100 |

32,417.3 |

|

Targeting and long range strike |

◔ |

LAND8113, LAND19 |

3,634.2 |

|

Space and cyber |

◯ |

– |

– |

|

Amphibious capable combined-arms land system |

◑ |

LAND121, LAND907, LAND4503, LAND400 |

14,824.5 |

|

Expeditionary air operations |

◑ |

AIR5439, AIR6000, AIR555, AIR7001 |

24,838.8 |

|

Missile defence |

◑ |

AIR6500, AIR2025, SEA1448 |

2,777.1 |

|

Theatre logistics |

◯ |

– |

– |

|

Theatre command and control |

◑ |

LAND200, AIR5431, SEA1442 |

2,426.8 |

|

Guided weapons and explosive ordnance |

◯ |

– |

– |

|

Enhanced and resilient northern bases |

◯ |

– |

– |

|

Enterprise infrastructure |

◯ |

– |

– |

|

Investment in enterprise data |

◯ |

– |

– |

Key: ◔ represents approximately a quarter of the capability element covered by MPR projects.

◑ represents approximately half of the capability element covered by MPR projects.

◯ no elements of the capability are covered by MPR projects.

Note a: The budget figures are total approved project budget as at 30 June 2025.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2024 IIP and 2024–25 MPR projects list and budgets in the PDSSs.

Rationale for undertaking the review

The MPR is commissioned by the JCPAA in the public interest to improve accountability and transparency.

1.10 The JCPAA has stated that the objective of the MPR is ‘to improve the accountability and transparency of Defence acquisitions for the benefit of Parliament and other stakeholders.’7 The JCPAA commissions the MPR in the public interest, for the benefit of users of the report inside and outside the Parliament. The MPR informs parliamentary scrutiny and the national conversation on major Defence acquisitions.

1.11 Defence’s major acquisition projects are the subject of parliamentary and public interest due to their: high cost and contribution to national security in a changing strategic environment; the challenges involved in completing them within the specified budget, schedule and to the required capability; and their contribution to industrial and employment policy objectives.

Conduct of the review

The MPR is a limited assurance review, which validates the accuracy and completeness of information provided by Defence in the PDSSs.

1.12 The ANAO has reviewed the PDSSs prepared by Defence as a ‘priority assurance review’ under subsection 19A(5) of the Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act), which allows the ANAO full access to the information gathering powers under the Act. The level of assurance that the ANAO aims to provide differs depending on whether the engagement is a performance audit (a reasonable assurance engagement) or an assurance review (a limited assurance engagement). The ANAO’s review of the PDSSs is a limited assurance engagement which is performed under ANAO Auditing Standards, which includes ASAE 3000 Assurance Engagements.8 A limited assurance engagement provides a lower level of assurance than a performance audit based on the procedures performed. In performing the limited assurance review of the PDSSs, we primarily relied on representations made by entity’s officials and examination of documents to validate the accuracy, completeness and governance of the information presented in the PDSSs.

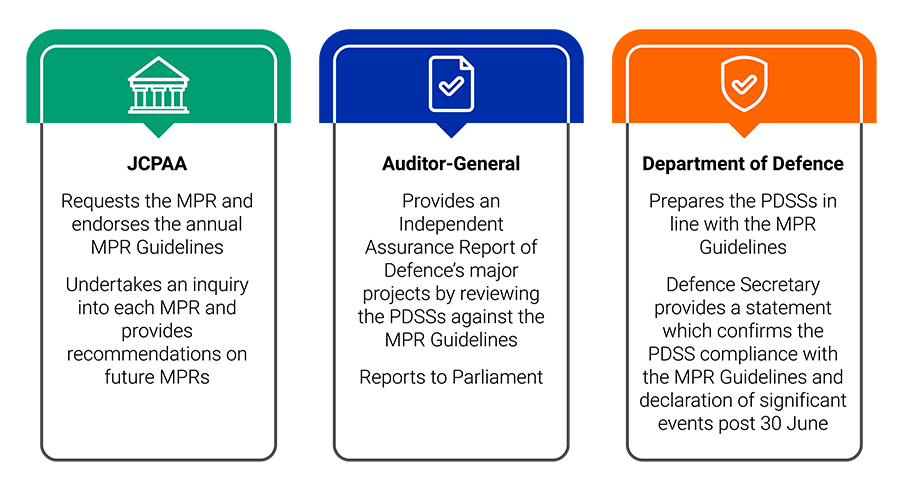

1.13 The scope of the MPR engagement is set out in the 2024–25 MPR Guidelines9 (included in Part 4 of this report), endorsed by the JCPAA following consultation between the ANAO and Defence. The key roles and responsibilities of the JCPAA, Auditor-General and Defence in delivering the MPR are set out in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Major Projects Report — Key roles and responsibilities

Source: ANAO analysis.

1.14 The MPR is tabled in the Parliament and is structured into four parts.

- Part 1 — includes the ANAO chapters which cover review and analysis, and the ANAO’s assessment of selected Defence systems and controls, including the governance and oversight in place to ensure appropriate project management.

- Part 2 — comprises Defence’s commentary, analysis and appendices, also referred to as the Defence MPR (not included within the scope of the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General).

- Part 3 — incorporates the Auditor-General’s Independent Assurance Report, the Statement by the Secretary of Defence, and the PDSSs prepared by Defence.

- Part 4 — reproduces the Major Projects Report Guidelines endorsed by the JCPAA, which provide the template for the PDSSs.

1.15 The Statement by the Secretary of Defence provides the final status of the 21 major projects as at 30 June 2025. The ANAO’s review includes an assessment of this statement, of which the PDSSs form part, and consideration of declared significant events occurring in projects after 30 June 2025 and before tabling of the MPR in the Parliament.

1.16 The Auditor-General’s Independent Assurance Report has previously excluded from scope several components of the PDSSs. For the 2024–25 MPR, all components of the PDSSs are included in scope of the Independent Assurance Report. The MPR now includes the following components that were previously excluded:

- Sections 1.2 and 4.1 — Current status and Measures of Materiel Capability/Scope Delivery Performance;

- Sections 1.3 and 5 — Major Risks and Issues;

- Section 2.4 – Australian Industry Capability (AIC); and

- forecast dates in the PDSSs.

1.17 The ANAO’s review was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost of approximately $1.6 million. This is a reduction in cost from prior years, reflecting process efficiencies identified by the ANAO and improvements in the quality of PDSSs submitted by Defence.

Review methodology

The review methodology sets out the ANAO’s approach to conducting the limited assurance review of the PDSSs.

1.18 The ANAO’s review of the information presented in the PDSSs include:

- assessing Defence’s internal systems, controls, and assurance mechanisms;

- reviewing documentation and engaging with Defence personnel;

- considering feedback from industry contractors on draft PDSS content;

- verifying Defence’s representations that support lessons learned;

- analysing project data across cost, schedule, capability/scope delivery and risks;

- evaluating senior management attestations regarding PDSS accuracy and completeness;

- reviewing financial assurance statements from the Chief Finance Officer;

- confirming security-related decisions by the Vice Chief of the Defence Force regarding the non-disclosure of certain information in the PDSSs; and

- reviewing the Statement by the Secretary of Defence, including post–30 June 2025 events and related representations.

1.19 When reviewing the PDSSs, the ANAO also considered the following Defence acquisition governance arrangements: Independent Assurance Review (IAR) process; Projects of Interest and Projects of Concern lists; Defence risk management policies and guidance, reporting and record-keeping (particularly of government decisions); Smart Buyer Framework; and the AIC requirements.

1.20 In addition to the review procedures performed in relation to the PDSSs, the ANAO has undertaken an analysis of the PDSSs for selected elements of project performance.

Auditor-General and Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit reports

Auditor-General reports tabled in the Parliament 2024–25

The Auditor-General tabled three performance audits that related to projects in the 2024–25 MPR, and another audit commenced in 2024–25.

1.21 The ANAO’s Annual Audit Work Program includes performance audits of Defence’s procurement of major specialist military equipment. Key areas of deficiency generally reported in performance audits includes: the need to improve focus on value for money; the completeness of advice; records management; and the management of probity.

1.22 In 2024–25, the ANAO undertook three performance audits related to projects included in the MPR, which provide a ‘reasonable assurance’ level review.

- Auditor-General Report No. 50 2024–25 Department of Defence’s Sustainment of Canberra Class Amphibious Assault Ships (Landing Helicopter Dock) found that Defence’s arrangements for the sustainment of Navy’s Landing Helicopter Dock ships were partly effective and made nine recommendations aimed at improving: the transition from acquisition to sustainment; the management of sustainment; and contract management.10

- Auditor-General Report No. 46 2024–25 Management of the OneSky Contract found that the arrangements for Airservices Australia’s management of the joint civil–military air traffic management system (CMATS) contract were partly effective. The audit made five recommendations relating to Airservices: contract management plan; risk management; documentation of contract variations; performance management; and guidance for gifts, benefits and hospitality.11

- Auditor-General Report No. 31 2024–25 Maximising Australian Industry Participation through Defence Contracting found that Defence had not maximised Australian industry participation through the administration of its contracts. The audit made nine recommendations to Defence aimed at improving governance, assurance and reporting arrangements.12

1.23 In 2024–25, the ANAO commenced a performance audit on the effectiveness of Defence’s procurement of Infantry Fighting Vehicles (LAND400 Phase 3).13 The audit will examine whether Defence conducted an effective tender process and established effective contract arrangements.14

1.24 Defence is also subject to ANAO financial statements auditing as required by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. Financial statements auditing includes aggregate financial reporting and disclosures relating to supplier expenses, assets under construction, and specialist military equipment. The valuation of specialist military equipment, general assets and assets under construction are audit focus areas. Financial statements audits provide a ‘reasonable assurance’ level.

1.25 From 2024–25, the ANAO commenced auditing Defence’s annual performance statements. A key activity in Defence’s Corporate Plan 2025–29 includes performance measure ‘6.1 — Defence is delivering the right future capability at the right time within the Integrated Investment Program to ensure it is equipped to respond to future security challenges as directed by the NDS’. This measure is supported by three targets.

- Target 6.1a: 80 per cent or more of approved Integrated Investment Program projects by domain are on track to deliver the scope approved by Government.

- Target 6.1b: 80 per cent or more of approved Integrated Investment Program projects by domain are on track to deliver within the schedule approved by Government.

- Target 6.1c: 80 per cent or more of approved Integrated Investment Program projects by domain are on track to deliver with the cost (including contingency) approved by Government.15

1.26 In Defence’s 2024–25 annual performance statements, against performance measure target 6.1b, Defence reported a result of ‘substantially achieved’. Defence’s performance reporting for project slippage against performance measure 6.1 is against amended budgets and timelines that have been approved by government decisions. In contrast, analysis of project slippage in the MPR measures project slippage against the original government approved FOC milestone, regardless of whether the decisions to amend the timelines were approved by government or not (as measured by the MPR through project-level FOC reporting). In 2024–25, the ANAO issued an unmodified audit report on the Defence Annual Performance Statements with an Emphasis of Matter drawing attention to the methodology used to calculate the results for scope, schedule and cost targets of performance measure 6.1.

JCPAA Inquiries into the Major Projects Report

The JCPAA made four recommendations with respect to the 2022–23 MPR — two for both Defence and the ANAO and two for Defence.

1.27 The JCPAA’s Inquiry into the 2022–23 Major Projects Report focussed on: the increased non-disclosure of information in the PDSSs and the need to maintain transparency; the lessons learned process; the Australian Industry Capability plans; the implementation of Defence’s risk management system; use of contingency funds; and the use of terminology. Report 507—Defence 2022–23 Major Projects Report16, was tabled in December 2024 and the JCPAA made four recommendations for the ANAO and Defence.

1.28 The JCPAA has held an inquiry into the matters contained and associated with Auditor-General Report No. 20 2024–25: 2023–24 Major Projects Report.17 The inquiry report is yet to be published.

2. Major projects review

Summary of analysis

The ANAO is unable to publish full longitudinal analysis due to Defence’s non-disclosure of key milestone data in PDSSs. Key performance indicators have improved since 2023–24.

2.1 Table 2.1 summarises the Project Data Summary Sheet (PDSS) aggregate data on Defence’s progress toward delivering the 21 projects in the review. This includes in-year data on cost, schedule and capability/scope delivery performance as well as total number of risks and issues published in the PDSSs.

Table 2.1: Summary of aggregate Project Data Summary Sheet key elements 2024–25a

|

Major Projects Report 2024–25 |

|

|

Number of projects |

21 |

|

Cost performance |

$m |

|

Total approved budget as at 30 June 2025 |

81,536.5 |

|

Total approved budget at final government second pass approvalb |

74,661.4 |

|

Total expenditure against total approved budget |

37,355.9 |

|

Total in-year expenditure against in-year budget |

5,329.5 |

|

Total budget variation since initial government second pass approval |

37,254.4 |

|

Total budget variation since final government second pass approval |

6,875.1 |

|

In-year approved budget variation |

775.9 |

|

Schedule performance |

months |

|

Average slippage (across all projects)c e |

21 |

|

Median slippage (across all projects)d e |

21 |

|

In-year schedule slippage |

4 |

|

Capability/scope delivery performance (Defence reporting) |

% |

|

● High level of confidence of delivery |

97.7 |

|

● Under threat, considered manageable |

1.1 |

|

● Unlikely to be met or removed from scope |

1.2 |

|

● Added to scope |

0 |

|

Risks and issuesf |

|

|

Total reported risks |

74 |

|

Downgraded or retired risks |

27 |

|

Total reported issuesg |

34 |

|

Downgraded or retired issues |

23 |

Note a: In prior MPRs, this table reported three years of longitudinal analysis, however the 2024–25 data is not comparable to prior years due to changes in the projects being reviewed in the MPR, and the non-disclosure of key milestone data in PDSSs.

Note b: Government second pass approval endorses a specific capability solution and provides authority for a project to begin acquisition.

Note c: Slippage refers to a delay in the current forecast date compared to the original government approved date of FOC. These figures exclude delays to a project’s schedule that do not result in slippage past the original government approved date, and schedule reductions over the life of the project.

Note d: Median slippage is a measure of central tendency and is not impacted by extreme outliers, for example projects that had a significant level of slippage.

Note e: Slippage analysis excludes two projects which did not have settled FOC dates as at 30 June 2025. SEA5000 Hunter Class Frigate did not have an FOC milestone approved by government and AIR6500 Integrated Air and Missile Defence Command and Control project has yet to define FOC.

Note f: Downgraded risks or issues are those previously reported in the PDSSs and internally managed by Defence as ‘High’ or above which are now downgraded to ‘Medium’ or lower. Retired risks or issues are those that no longer require management by Defence. All downgraded and retired risks and issues will be removed from subsequent MPRs.

Note g: One project (SEA9100 IE Logistics Helicopter) included an issue marked as ‘not for publication’.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2024–25 PDSSs.

2.2 Budget variations since initial Second Pass Approval total $37,254.4 million. Of this, AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B Joint Strike Fighter and SEA5000 Hunter Class Frigate account for 80.9 per cent ($30,134.7 million) due to an increase in 58 aircraft for AIR6000, and approval to commence construction of one to three ships for SEA5000 (see paragraph 4.3).

2.3 The ANAO undertook trend analysis on 14 projects18 that have been in the MPR across five consecutive years, from 2020–21 to 2024–25 (further data is available from paragraph 4.38). The reason for selecting the 14 projects was to ensure comparative analysis by excluding projects entering or exiting the MPR.

2.4 Project slippage is calculated based on the variance between original government second pass approval (when government originally expected capability to be available) and current project completion forecasts (FOC milestone). As the projects in the MPR are delivered concurrently, measuring median and average slippage is a measure of project delivery performance across the 21 projects. The median value, by excluding outliers, provides an indication of the typical impact on achieving FOC on a project-level basis. The median slippage and the average slippage are 21 months respectively (see Table 2.1). This analysis excludes SEA5000 Hunter Class Frigate, which did not have an FOC milestone approved by government and AIR6500 Integrated Air and Missile Defence Command and Control, which has yet to define FOC. The sum of individual project slippage across the 21 projects is 404 months. AIR5431 Phase 3 CMATS represents the largest contributor, accounting for 23 per cent (93 months) of the slippage (see paragraphs 4.20 and 4.21).

2.5 During the 2024 IIP rebuild process, some projects were rephased as programs or tranches and the baseline for FOC was reset with the introduction of new Material Acquisition Agreements (MAAs). This means that the schedule performance for affected projects is generally reset at zero within the longitudinal schedule analysis. Project-level longitudinal analysis is unable to be conducted across affected projects when project delivery milestones have been adjusted without risking disclosure of information previously marked as not for publication (NFP) in prior years.

2.6 Section 4 on the PDSSs presents a forecast of the capability to be delivered for the project, by FOC, and does not represent schedule or budget performance. Materiel capability is visualised by a traffic light rating system of ‘green’, ‘amber’ or ‘red’. Within this, section 4.1 provides a likelihood forecast of the capability to be delivered by the project against the FOC milestone. A description of the materiel release and operational capability elements for FOC is defined in Section 4.2 of the PDSS.

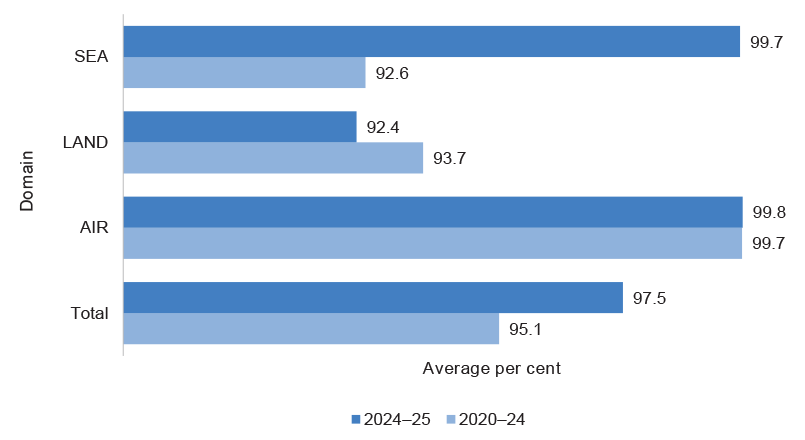

2.7 Figure 2.1 provides a high-level longitudinal summary of capability/scope disclosures across the 14 projects, comparing the average performance from 2020–21 to 2023–24, to the in-year performance in 2024–25. This shows there has been an improvement in delivery confidence levels for scope and capability, which have seen a year-on-year improvement in reported ‘green’ capability. For example, in the SEA domain, the high level of delivery confidence (‘green’ rating) was 99.7 per cent for 2024–25, which is significantly higher than the average reported ‘green’ rating from 2020–21 to 2023–24.

Figure 2.1: Average high level of confidence in capability by domain, for projects consistent in the MPR from 2020–21 to 2023–24 compared to 2024–25

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2020–21 to 2024–25 PDSSs.

2.8 A comparison to the 2023–24 MPR explaining the differences in the above analysis is unable to be published by the ANAO due to the non-disclosure of FOC dates, forecast dates and other capability related information by Defence.

Summary of the Auditor-General’s conclusion

2.9 The Auditor-General’s Independent Assurance Report for 2024–25 is found in Part 3 of this report. Based on the review procedures and the evidence obtained, the Auditor-General concluded that nothing came to her attention that caused her to believe that the information reviewed was not prepared in accordance with the 2024–25 MPR Guidelines.

2.10 The Auditor-General also included an Emphasis of Matter paragraph to draw attention to disclosures within the Statement by the Secretary of Defence (found in Part 3 of this report) that information has been removed from the relevant PDSSs due to Defence’s assessment that the information would or could reasonably be expected to cause damage to the security, defence or international relations of the Commonwealth.

Statement by the Secretary of Defence

2.11 The Statement by the Secretary of Defence (Part 3 of this report) was signed on 8 December 2025. The Secretary’s statement provides his opinion that the PDSSs for the 21 major acquisition projects, which form part of the MPR ‘comply in all material respects with the Guidelines and reflect the status of the projects as at 30 June 2025’.

2.12 The Secretary’s statement notes the significant subsequent project events that occurred post-30 June 2025 as well an update on Projects of Interest and Projects of Concern. This also outlines the security classification review on the material presented in the PDSSs to ensure only unclassified information is published and anything that has been withheld was marked in the PDSSs as NFP or delayed.

Not for publication (NFP) information by Defence

The amount of information marked as NFP in the PDSS has significantly increased from 2021–22 to 2024–25, reducing the ANAO’s capacity to publish longitudinal analysis.

2.13 The 2024–25 MPR Guidelines sets out the information to be included in an unclassified manner by Defence in its PDSSs, including forecast dates and capability related information. The 2024–25 Guidelines also state that:

Defence is responsible for ensuring that information of a classified nature is made available to the ANAO for review, as it relates to the data contained within the PDSSs. Defence will provide data for inclusion in the final MPR in a way that allows for unclassified publication. Defence will provide advice to the ANAO on the classification of information in individual PDSSs and the aggregated security classification of information contained across all PDSSs.

2.14 Defence marks information as NFP in the PDSSs where it has assessed that some details, both with respect to independent projects and in the aggregate, would or could reasonably be expected to cause damage to security, defence or international relations to the Commonwealth without sanitisation of the data. While not disclosing information in this report, Defence has provided all information necessary to the ANAO to conduct its review, as required by the 2024–25 MPR Guidelines.

2.15 NFP information is determined through representations made by the Vice Chief of the Defence Force (VCDF) to the Secretary, advising the non-disclosure of selected information for publication after performing a security review over the PDSSs. In the 2024–25 MPR, 19 of the 21 projects included information marked as NFP, for example the non-disclosure of FOC dates, and therefore this information has not been disclosed in the published PDSSs. The full list of the PDSSs and the respective sections, which have been marked as NFP by Defence is in the Auditor-General’s Independent Assurance Report in Part 3 of this report.

2.16 This application of NFP has led to four successive Emphases of Matter in the Auditor-General’s Independent Assurance Reports (2021–22 to 2024–25). These draw attention to the non-disclosure of certain information by Defence in its reporting on projects, including project-level capability milestones and forecast delivery dates. 19 The number of projects in prior years containing non-disclosures were 20 in 2023–24; 12 in 2022–23; and four in 2021–22. The change from 20 projects in 2023–24 containing non-disclosures, to 19 projects in 2024–25, is in relation to SEA3036 Phase 1 Pacific Patrol Boat Replacement where the prior year non-disclosures were removed.20 The impact of non-disclosure has reduced the level of transparency to the Parliament and stakeholders.

2.17 The issue of transparency was raised in two reports by the JCPAA – Report 503: Inquiry into the Defence Major Projects Report 2020–21 and 2021–22 and Procurement of Hunter Class Frigates21 and Report 507—Defence 2022–23 Major Projects Report22 relating to its annual inquiries on the MPR. This issue remains outstanding and was also discussed at the November 2025 JCPAA inquiry into the 2023–24 MPR (see paragraphs 1.27 to 1.28).

2.18 The level of information subject to NFP has led to the ANAO’s inability to provide complete schedule and project performance analysis since it was last published in the 2020–21 MPR. This has historically involved both in-year analysis (across the current MPR projects) and longitudinal analysis (across all projects included in the MPR over time). Such information is now provided in aggregate or in summarised form to not identify the individual impacted projects.

Minimum Viable Capability

Minimum viable capability is a new milestone introduced by Defence in 2023 and has been applied to one project in the 2024–25 MPR.

2.19 Following the Defence Strategic Review 2023, Defence introduced the term Minimum Viable Capability (MVC) as an acquisition milestone. The 2024 National Defence Strategy23 states that:

A minimum viable capability is a capability that can be introduced into service successfully, sustained effectively and achieve the directed effect in the required time. It is underpinned by minimum viable products, which achieve or enable the lowest acceptable mission performance in the required time. This approach retains a focus on value for money, but places greater emphasis on speed to acquisition.

2.20 MVC is designed to deliver capabilities faster, more flexibly, and with greater responsiveness to strategic priorities. In late 2025, Defence commenced development of a framework to support how MVC will be applied to projects in practice. On 29 September 2025, Defence advised the ANAO that since the concept was introduced in 2023 ‘it has become apparent that MVC involves a range of complex, inter-related processes’. Defence further advised that ‘IOC [Initial Operating Capability] and FOC remain the authoritative project delivery milestones for all capability projects and continue to serve as the primary metrics for assessing delivery of Defence materiel’.

2.21 In the 2024–25 MPR, Defence has applied MVC to one project — AIR6500 Integrated Air and Missile Defence Command and Control. Government second pass approval was based on an MVC milestone rather than the traditional IOC and FOC milestones. In the 2024–25 PDSS, Defence has yet to define an IOC or FOC date for this project. PDSS data pertaining to AIR6500 Integrated Air and Missile Defence Command and Control is not comparable with other projects that have a defined IOC and FOC and has therefore been excluded from analysis on schedule performance and materiel capability/scope delivery performance. The relevant tables or figures have accompanying notes identifying where this information has been excluded from the analysis. As this is the first year the project has been reported in the MPR, the impacts from the application of MVC as a milestone are unknown.

3. Results of the ANAO’s review

PDSS preparation and review process

In 2024–25, the overall quality of the PDSS preparation has improved from previous years.

3.1 Defence prepares Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) for the 21 selected major projects in accordance with the 2024–25 MPR Guidelines, which are required to be presented fairly and are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. A quality PDSS preparation and review process by Defence reduces the risk of untimely and/or inaccurate reporting. This will reduce the incidence of multiple reviews by the ANAO for the same project to ensure the required standard, as set by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) through the MPR Guidelines, has been met.

3.2 In 2024–25, Defence provided three versions (includes two drafts and a publication version) of the PDSSs for the ANAO’s review between May and October 2025. Early in the 2024–25 PDSS assessment process, the ANAO recognised the implementation of an improved quality assurance program by Defence and the development of key artefacts to support project teams in developing their PDSS. Quality issues identified in previous MPRs decreased significantly in the ANAO’s first review of all 21 PDSSs, with a decrease from 1,038 to 461 actions24 (44 per cent reduction) associated with the review in 2024–25 when compared with 2023–24. These improvements continued to be observed into the second review with a reduction of 38 per cent fewer actions.25

Project reporting improvements

3.3 Throughout the MPR series, the ANAO reviews coupled with the annual JCPAA inquiries into the report, have contributed to accountability and improved governance of Defence major projects, despite Defence’s recent increase in information marked as NFP. This includes but is not limited to:

- expanded efforts to centralise and standardise risk reporting, including adopting the ‘Predict!’ enterprise risk tool;

- enhanced compliance reviews to improve project governance;

- automated reporting on budget estimates, actual expenditure, and contingency usage;

- improved records management and reporting of Project of Concern (POC) and Project of Interest (POI) to Minister for Defence Industry;

- established the Lessons Governance Board to assess project and enterprise strategic lessons;

- reduced year on year liquidated damages;

- introduced accountability for the development of Australian Industry Capability plans; and

- developed automation of Defence processes to improve the quality of PDSS preparation.

Lesson learned section of PDSSs

In 2024–25, Defence improved its disclosure of lessons learned, which meant that the previous year’s qualification by the Auditor-General was resolved.

3.4 In the 2022–23 and 2023–24 MPRs, the Auditor-General’s Independent Assurance Report included a qualified conclusion due to insufficient audit evidence to determine whether Defence’s disclosures in Section 6 of the PDSSs, relating to lessons learned, was in accordance with the requirements of the MPR Guidelines.

3.5 The disclosures in section 6 of the 2024–25 PDSSs have been expanded from those in the 2023–24 MPR to clearly indicate lessons that are strategic in nature and those that are assessed as project level (non-strategic). This change was made to address both the prior year Auditor-General qualified conclusion and to bring forward implementation of recommendation 1 from the JCPAA Report 507.26

3.6 Defence has implemented a CASG MPR Lessons Board (chaired by a Senior Executive Service (SES) Band 2 official), which provides some assurance over the current year lessons disclosures in the PDSSs. Board minutes analysed also identified that remediation activities have commenced to address open lessons findings.

3.7 New manual controls have been implemented by the Defence project teams. These include review and sign off on lessons information by a SES Band 1 official, categorisation between strategic and project lessons, and documenting the decision process in selecting lessons for disclosure from those recorded in the Defence Lessons Repository.

3.8 In 2024–25, the Auditor-General has not issued a qualification over Defence’s disclosures in Section 6 of the PDSSs relating to lessons learned and has determined that the requirements of the MPR Guidelines have been met.

Defence acquisition governance

Defence utilises various governance and oversight mechanisms to support the management of acquisition projects.

3.9 Consistent with prior years, the ANAO considered Defence’s major project acquisition governance processes when planning and conducting the review for the 2024–25 MPR. While some of these processes are well established, others have not yet been fully implemented to achieve their intended impact. More detail can be found in Defence’s Part 2 of this report. Table 3.1 summarises each area that the ANAO observed and accompanying findings.

Table 3.1: ANAO analysis of Defence acquisition governance activities relating to the MPR

|

Defence governance arrangements |

ANAO assessment |

|

Independent Assurance Reviews (IARs) IARs are a review process that assures the Defence Executive that projects meet approved objectives within scope, schedule, and budget, and are ready for the next stage. IARs are typically undertaken in the lead up to Investment Committee consideration before major project milestones. |

During 2024–25:

|

|

Materiel Acquisition Agreements (MAAs) MAAs document the internal arrangements between CASG and the Defence Service Chiefs and confirm project requirements and approved activities. They draw on original approval documents, such as government decisions, and are reviewed as required to manage changes to capability, schedule, and cost with Defence contractors. MAAs also provide data for Defence business reporting systems. MAAs are monitored and reported monthly and must be established both before and after government approval for project funding. |

During 2024–25, 15 of the 21 projects had an MAA that was approved between 2023 and 2025:

|

|

Projects of Concern (POC) and Projects of Interest (POI) The POC process provides ministerial oversight to remediate underperforming projects through collaboration with senior Defence leadership and industry partners. The POI process is a Defence-led monitoring program to identify and address issues early to prevent an escalation to POC. |

Table 3.2 below outlines the two MPR projects classified as POC (2023–24: 2) and the six MPR projects classified as POI (2023–24: 7). |

|

Smart Buyer Framework The Smart Buyer Framework is typically undertaken following a project’s entry to the IIP, or to support ongoing strategy development. It identifies key project strategy drivers, and appropriate procurement and contracting methodologies, prior to consideration by the Investment Committee at each decision point. Application of the framework supports Defence to deliver value for money while optimising capability outcomes. |

Of the two projects entering the MPR in 2024–25 — LAND8113 Phase 1 Long Range Fires and AIR6500 Integrated Air and Missile Defence Command and Control — both applied the Smart Buyer framework. Smart Buyer activity has also been conducted in 2024–25 for two MPR projects (SEA1180 Phase 1 Offshore Patrol Vessel and SEA9100 Phase 1 IE Logistics Support Helicopter). |

|

Australian Industry Capability (AIC) A program that aims to provide Australian businesses the opportunity to compete for Defence work based on merit, influence foreign prime contractors and original equipment manufacturers to deliver cost-effective support, and encourage investment in Australian industry. AIC schedules and plans should describe how a tenderer has engaged with Australian industry to deliver the required goods, works or services. AIC schedules are required for materiel procurements valued between $4 million and $20 million. AIC plans are required for materiel procurements valued at $20 million or more. |

Seven of the 21 projects (2023–24: 5) did not have AIC plans in place.d Examples of reasons provided in the PDSSs included:

A further 10 projects had not published a public plan for one or more of their eligible contractors. |

Note a: The following projects underwent IARs in 2024–25 however the reports were finalised in 2025–26: AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B Joint Strike Fighter; AIR7001 MQ-4C Triton; AIR555 MC-55A Peregrine; AIR5341 Phase 3 CMATS; and SEA3036 Phase 1 Pacific Patrol Boat Replacement.

Note b: The projects with most recent MAAs finalised between calendar years 2021 to 2023 were: LAND400 Phase 2 Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles; AIR555 MC-55A Peregrine; LAND907 Armoured Combat; SEA1439 Phase 5B2 Collins Comms and EW.

Note c: Projects with most recent MAAs finalised prior to 2021: SEA1180 Phase 1 Offshore Patrol Vessel and LAND121 Phase 4 Hawkei.

Note d: The projects that did not have an AIC plan were: AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B Joint Strike Fighter, AIR555 Phase 1 Peregrine, AIR7001 MQ-4C Triton, LAND4503 Phase 1 ARH Replacement, LAND8113 Phase 1 Long Range Fires, LAND200 Tranche 2 Battlefield Command System, and SEA9100 Phase 1 IE Logistics Support Helicopter.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2024–25 PDSSs.

Projects of Concern and Projects of Interest

Of the 21 projects in the 2024–25 MPR, Defence had classified two as Projects of Concern (POC) and seven as Projects of Interest (POI).

3.10 Defence considers placing an acquisition project on the POI or POC list when significant risks or issues, and/or breaches of project parameters have been identified through its internal reporting and/or oversight mechanisms.

- The POC process intends to manage the remediation of underperforming projects. This process is led by the Minister for Defence Industry through joint collaboration with senior Defence officials and industry management, and the development of a plan to resolve issues.

- The related POI process is where projects are monitored internally by Defence to ‘ensure issues are remediated and that the projects does not progress to a POC’.

3.11 As at 30 June 2025, as set out in Table 3.2, two MPR projects were classified as POC (2023–24: 2 — same projects) and seven projects were POI (2023–24: 7 — same projects).

Table 3.2: 2024–25 MPR Projects of Concern and Projects of Interest

|

Projects of Concern |

|

AIR5431 Phase 3 CMATS |

|

SEA1180 Phase 1 Offshore Patrol Vessel |

|

Project of Interest |

|

SEA5000 Hunter Class Frigates |

|

AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B Joint Strike Fighter |

|

LAND400 Phase 2 Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles |

|

AIR555 Phase 1 Peregrine |

|

LAND121 Phase 4 Hawkei |

|

AIR2025 Phase 6 JORN Mid-Life Upgrade |

|

LAND200 Tranche 2 Battlefield Command System |

Note: AIR2025 Phase 6 JORN Mid-Life Upgrade exited the POI list in August 2024.

Source: Defence June 2025 Projects and Products of Interest and Concern.

Projects of Concern

3.12 AIR5431 Phase 3 CMATS was listed as a POC between August 2017 and May 2018 due to extended contract negotiations that delayed its formal commencement. After the contract was signed, AIR5431 Phase 3 CMATS was managed as a POI until October 2022, when it was reclassified as a POC. This decision was based on the project facing significant schedule, technical and cost challenges. Schedule delays are discussed further from paragraph 4.16. The anticipated exit date of AIR5431 Phase 3 CMATS from the POC list is mid-2027.

3.13 SEA1180 Phase 1 Offshore Patrol Vessel was listed as a POC on 20 October 2023 due to delays affecting both ship construction and the associated support system. On 20 February 2024, the Australian Government announced that SEA1180 Phase 1 Offshore Patrol Vessel would be reduced from 12 to six vessels. Defence and the contractor have committed to jointly addressing the project’s challenges through a POC remediation plan.

Projects of Interest

3.14 The seven MPR projects that were listed as POIs are discussed below.

- SEA5000 Hunter Class Frigates — A POI since March 2020 due to significant challenges in schedule, technical complexity, workforce availability and cost. Despite progress (including the transition to the construction phase for the first three ships in June 2024) the project continues to face risks related to design maturity and integration.

- AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B Joint Strike Fighter — a POI since June 2017 due to its strategic importance and early concerns about achieving IOC. Although IOC was declared on schedule in December 2020, the project remains under scrutiny due to its scale and complexity. A case study on the history of this project since entering the MPR in 2011 is presented at paragraph 3.38, noting that the 2024–25 MPR is the last year the project will be reported.

- LAND400 Phase 2 Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles — added to the POI list in June 2024 due to the complexity of delivering both LAND400 Phase 2 and the Boxer Heavy Weapon Carrier Export project. Persistent schedule pressures continue to affect the achievement of the FOC milestone.

- AIR555 Phase 1 Peregrine — a POI since September 2023 due to delays in the aircraft flight test program.

- LAND121 Phase 4 Hawkei — a POI from December 2018 to May 2021 and from July 2023, primarily due to unresolved brake issues and operating restrictions across the ADF fleet.

- AIR2025 Phase 6 JORN Mid-Life Upgrade — a POI since September 2019 due to unrecoverable delays in engineering design milestones, which has disrupted the original schedule for Initial and Final Materiel Release.

- LAND200 Tranche 2 Battlefield Command System — since September 2018 due to issues associated with vehicle integration and realisation of risks resulting in the request to access contingency funding.

3.15 From June 2023, the Minister for Defence Industry requested monthly POC and POI reporting. Monthly reports and the Quarterly Performance Reports are reviewed by the ANAO as part of the PDSS reviews to validate the POC and POI in the MPR.

Project budget and expenditure

Of the 21 MPR projects, one stated that there was insufficient budget for the project to be completed against the agreed scope.

Project financial assurance statement

3.16 The 2011–12 MPR introduced the project financial assurance statement, which is the project’s assessment of its budget sufficiency for the delivery of agreed capability/scope. The contingency statement has been included since the 2013–14 MPR. It is a description of the use of contingency funding to mitigate project risks during the reporting period. These statements aim to provide transparency over the project’s financial status.

3.17 A project’s total approved budget comprises of:

- allocated budget, which covers the project’s approved activities set out in the MAA; and

- contingency budget, which is set aside for the eventuality of risks occurring and includes unforeseen work that arises within the delivery of the planned scope of work.27

3.18 As at 30 June 2025, 20 of the 21 MPR projects stated that sufficient budget remained for the projects to be completed against the agreed scope. The exception was AIR5431 Phase 3 CMATS, which stated insufficient funds due to the extended project delivery duration, potential regulatory or compliance contract changes, rework of customer furnished services and ongoing external workforce requirements. The statement is restricted to Defence’s current financial contractual obligations for the project and current known risks and estimated future expenditure.

Caveats, deficiencies and contingencies

No caveats or deficiencies were declared and four projects either applied for or spent contingency funds.

3.19 In the PDSSs, Defence is required to declare any significant capability milestones with caveats or deficiencies, as well as the use of contingency funds.28

3.20 No caveats or deficiencies were declared in the 2024–25 MPR relating to the 21 projects.29

3.21 In 2024–25, four projects either spent or applied for contingency funds to manage project risks (2023–24: three).

- AIR5431 Phase 3 CMATS — for progressing the Air Traffic Management Capability Assurance Program under existing support arrangements for the Australian Defence Air Traffic System, and a CMATS remediation activity.

- LAND19 Phase 7B SRGB Air Defence — applied for contingency as a result of delays relating to the COVID-19 pandemic. Defence used quarantined funds for the Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air Missile Foreign Military Sale case for the treatment of these risks.

- SEA3036 Phase 1 Pacific Patrol Boat Replacement — primarily for engineering modifications, using part of the contingency funding applied for in 2022–23.

- AIR6500 Integrated Air and Missile Defence Command and Control — spent contingency associated with the application made in 2023–24 for price escalation.

3.22 In 2024–25, all 21 MPR projects complied with Defence’s financial policy relating to contingency funding. Defence policy states that a project’s contingency is to provide funding for cost, schedule and technical uncertainties that may materialise over the life of a project. The policy requires the project manager to maintain a project contingency log, which is intended to support management’s control of project contingency and facilitate reporting on its use. The use of contingency funding is dependent on the occurrence of a contingency risk event and contingency cannot be used to pay for activities, which could increase the scope of the capability project.

3.23 Two compliance issues emerged during the 2024–25 MPR review of project contingency logs.

- Lack of clarity of the relationship between contingency allocation and identified risks, an issue highlighted in previous MPRs.30 Two projects (LAND4503 Phase 1 Apache Attack Helicopter and SEA1448 Phase 4B ANZAC Air Search Radar Replacement) did not explicitly align the contingency log with the risk log to ensure that the expected cost impact of risks is maintained effectively.

- Insufficient timely review and updates of the contingency logs. A total of nine projects provided contingency logs that were not updated including: more than six months (seven projects)31; or more than 12 months (AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B Joint Strike Fighter); and one contingency log was not dated (AIR555 MC-55A Peregrine).

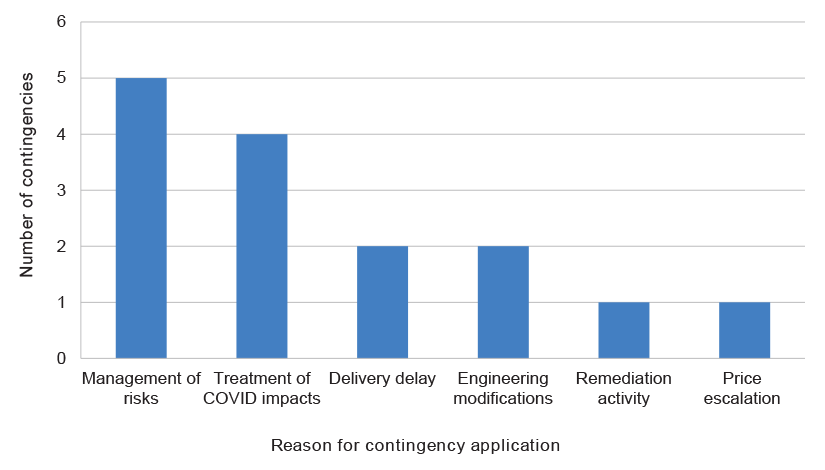

3.24 Table 3.3 sets out the projects that applied for or utilised contingency funds and Figure 3.1 provides a summary of the key reasons.

Table 3.3: Projects that either spent or applied for contingency funds between 2020–21 and 2024–25

|

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

2022–23 |

2023–24 |

2024–25 |

|

AIR9000 Phase 2/4/6 MRH90 Helicopters |

AIR9000 Phase 2/4/6 MRH90 Helicopters |

AIR9000 Phase 2/4/6 MRH90 Helicopters |

AIR5431 Phase 3 CMATS |

AIR5431 Phase 3 CMATS |

|

JNT2072 Phase 2B Battlespace Communications Systems |

SEA1180 Phase 1 OPV |

AIR5431 Phase 3 CMATS |

SEA3036 Phase 1 Pacific Patrol Boat Replacement |

SEA3036 Phase 1 Pacific Patrol Boat Replacement |

|

– |

LAND19 Phase 7B SRGB Air Defence |

LAND19 Phase 7B SRGB Air Defence |

LAND19 Phase 7B SRGB Air Defence |

LAND19 Phase 7B SRGB Air Defence |

|

– |

JNT2072 Phase 2B Battlespace Communications Systems |

– |

– |

AIR6500 IAMD Command and Control |

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2020–21 to 2024–25 PDSSs.

Figure 3.1: Reasons for contingency application between 2020–21 and 2024–25

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2020–21 to 2024–25 PDSSs.

Risk management

In 2024–25, all PDSSs contained risks and issues that Defence rated as ‘high’ or ‘very high’, with the number varying depending on factors including complexity or delivery stage of the project.

3.25 Defence standardised the use of Predict! as its corporate risk management system in May 2020.32 The ANAO’s review in 2024–25 identified that:

- all 21 projects offices utilised Predict! (no change from the 2023–24 MPR); and

- one project (AIR5431 Phase 3 CMATS) used Predict! and a bespoke SharePoint tool jointly with Airservices Australia, as Airservices Australia does not use Predict!.33

3.26 The 2024–25 PDSSs report both major risks and issues (those rated as ‘high’ and ‘very high’). Risks represent potential events that may impact project objectives. Issues are ‘high’ or ‘very high’ risks that have been realised or issues that have arisen that require immediate management action. The number of major risks and issues vary across the 21 MPR projects, reflecting factors such as the stage of the project and the complexity of the acquisition.

3.27 Figure 3.2 outlines the number of major risks and issues for each project in 2024–25. AIR5431 Phase 3 CMATS had the highest number of major risks (12) and is managing four issues, which is consistent with the POC status of the project. LAND907 Armoured Combat did not report any major risks or issues as it had reached the late stage of the project.

Figure 3.2: Total in-year reported risks and issues by project 2024–25a b c

Note a: Major project risks include risks and emergent risks reported in Section 5.1 and 5.2 of the PDSSs.

Note b: One project (SEA9100 IE Logistics Helicopter) included an issue marked as ‘not for publication’.

Note c: JORN Mid-Life Upgrade exited the POI list in August 2024.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2024–25 PDSSs.

3.28 Defence reported a total of 74 risks and 34 issues across the 21 PDSSs. This represents a total of 108 combined risks and issues, compared with a total of 71 in 2023–24. Analysis of the 2024–25 risks and issues is set out below.

- 19 risks (26 per cent) and seven issues (21 per cent) were in relation to the two POC projects (SEA1180 Phase 1 Offshore Patrol Vessels and AIR5431 Phase 3 CMATS).

- 28 risks and 15 issues were in relation to the six POI projects (SEA5000 Hunter Class Frigates, AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B Joint Strike Fighter, LAND400 Phase 2 Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles, AIR555 MC-55A Peregrine, LAND121 Phase 4 Hawkei and AIR2025 Phase 6 JORN Mid-Life Upgrade).

- 27 risks (36 per cent of all risks) and 23 issues (68 per cent of all issues) are reported as downgraded or retired and will be removed from the subsequent MPR.

3.29 For the 21 projects in the 2024–25 MPR, the number of major project risks and issues has varied across the three domains of LAND, SEA and AIR, see Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3: Total reported risks and issues by domaina

Note a: One project (SEA9100 IE Logistics Helicopter) included an issue marked as ‘not for publication’.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2024–25 PDSSs.

3.30 Projects within the AIR domain have the highest total number of major risks at 36 (49 per cent). Twelve of the major risks are in relation to AIR5431 Phase 3 CMATS. Under the OneSKY Australia program, Airservices Australia is the lead agency for the joint procurement of CMATS and Airservices Australia has entered into contracts for the acquisition and support of CMATS on behalf of Air Services Australia and Defence (see paragraph 1.22).

3.31 There were 18 major risks (24 per cent) for the SEA domain, and 20 (27 per cent) for the LAND domain. The AIR domain managed nine major issues, the lowest compared to the LAND domain (11) and the SEA domain (14).

3.32 Defence’s risk management has been a focus of the MPR since its inception in 2008–09. Risk management has also been reviewed by the JCPAA, most recently in its Inquiry into the Defence Major Projects Report 2020–21 and 2021–22 and Procurement of Hunter Class Frigates. In its June 2024 report on the inquiry, the Committee observed that:

… there are still inconsistencies in Defence’s risk management practices, although improvements have been made, and this still needs to be addressed going forward.34

3.33 Paragraph 3.3 outlines Defence’s efforts to centralise key governance processes, including risk management, however, the ANAO identified weakness in controls within Predict! in the 2022–23 MPR.35 These have not yet been addressed by Defence and continue to impact the effectiveness of the system and data quality. In the 2024–25 MPR, the ANAO identified the following issues.

- Variable compliance with corporate guidance. All 21 projects had an approved Risk Management Plan, however, three projects36 (AIR555 MC–55A Peregrine, AIR7001 MQ–4C Triton and SEA9100 Phase 1 IE Logistics Support Helicopter) were unable to demonstrate a review of their risk management plan as required by Defence policy.

- Lack of visibility of risks and issues when a project is transitioning to sustainment.

- Risks and issues logs are not reviewed and updated in a timely manner to ensure accurate, complete and up-to-date record of risks and issues.

- Lack of quality control resulting in inconsistent approaches in the recording of issues within Predict!.

Defence acquisition categories

3.34 Defence categorises projects into four acquisition categories (ACAT) of descending level of complexity, to aid in the management of risk:

- ACAT I projects are Defence’s most strategically significant major capital acquisitions;

- ACAT II projects are strategically significant major capital acquisitions;

- ACAT III projects are major or minor capital acquisitions of moderate strategic significance; and

- ACAT IV projects are major or minor capital acquisitions of lower strategic significance.

3.35 The number of ACAT I projects reported in the MPR has decreased over the past five years, and reporting of ACAT II and ACAT III projects has increased (see Table 3.4).

Table 3.4: ACAT ratings of projects between 2020–21 and 2024–25

|

Year |

ACAT I |

ACAT II |

ACAT III |

ACAT IV |

Total projects |

|

2020–21 |

10 |

11 |

0 |

0 |

21 |

|

2021–22 |

10 |

11 |

0 |

0 |

21 |

|

2022–23 |

10 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

20 |

|

2023–24 |

8 |

12 |

1 |

0 |

21 |

|

2024–25 |

7 |

13 |

1 |

0 |

21 |

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2024–25 PDSSs and previously published Defence PDSSs.

Use of different acquisition approaches

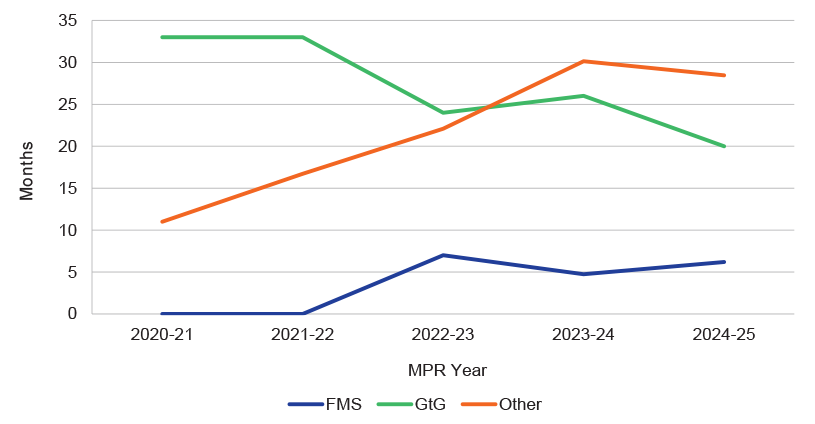

A combination of different acquisition approaches may be used simultaneously, or at different points, during a project’s delivery lifecycle.

3.36 The suite of current and historical PDSSs indicates that Defence has primarily acquired the major projects using the following approaches.

- Foreign Military Sales (FMS) — this is where the US Government and a foreign government enter an agreement called a Letter of Offer and Acceptance, in this case the foreign government is Australia. FMS cases tend to be acquisitions of mature platforms from existing production lines, for example LAND4503 Apache Attack Helicopter. There are a total of five projects using the FMS approach (see Table 1.1).

- Government-to-government (GtG) agreements — this is where the Australian Government and a foreign government enter into an arrangement, not an FMS acquisition, and is established through a Memorandum of Understanding, including co-operative agreements. These procurements are typically for developmental programs where Australia and another country will collaborate on the development of a platform, for example AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B Joint Strike Fighter. There are a total of three projects using the GtG approach (see Table 1.1).

- Other — these approaches typically involve direct contracts with commercial suppliers for developmental or domestic acquisitions. There are a total of 13 projects using the ‘other’ approach (see Table 1.1).

3.37 A project may have multiple approaches to acquiring different aspects of its scope. For example, AIR5349 Phase 6 Advanced Growler is being delivered through a GtG, FMS and a contract with a supplier. For the purposes of the analysis of this report, the ANAO has categorised projects based on their lead contract or primary acquisition arrangement.

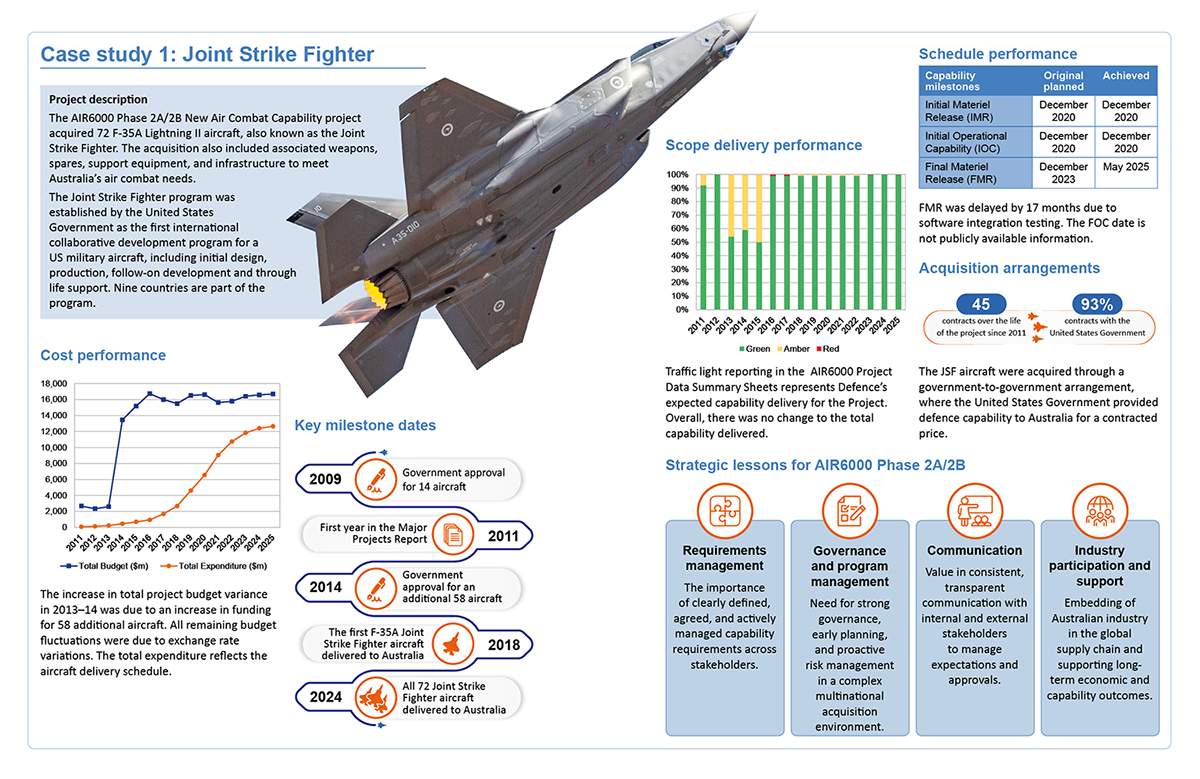

3.38 Case study 1 on AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B Joint Strike Fighter provides an overview of project performance since it was first reviewed in the 2010–11 MPR. This project has been the subject of the MPR review since 2008, is a GtG delivery and rated as an ACAT I (very high level of complexity) project by Defence. Overall, this project was delivered within budget and with no change to the total capability delivered, noting the project’s overall ‘green’ rating for scope delivery performance since 2016. The final materiel release date was 17 months later than planned, primarily due to software testing.

Case study 1: Joint Strike Fighter

4. Project performance analysis

4.1 The ANAO has undertaken an in-year analysis of the 21 PDSSs to review project performance in addition to its limited assurance review. The three performance elements analysed were cost, schedule and the delivery of capability/scope, as described in Figure 4.1. The ANAO has presented information in aggregate, average and median measures to analyse the three performance elements, selecting the most appropriate approach for each. This flexible methodology was necessary because a standardised format could not be adopted without risking unintended disclosure of not for publication (NFP) information contained in the Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs), which are prepared by Defence.

Figure 4.1: Project performance elements

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2024–25 MPR Guidelines.

Cost performance

The total expenditure for AIR domain projects is approximately double that of SEA and LAND domains.

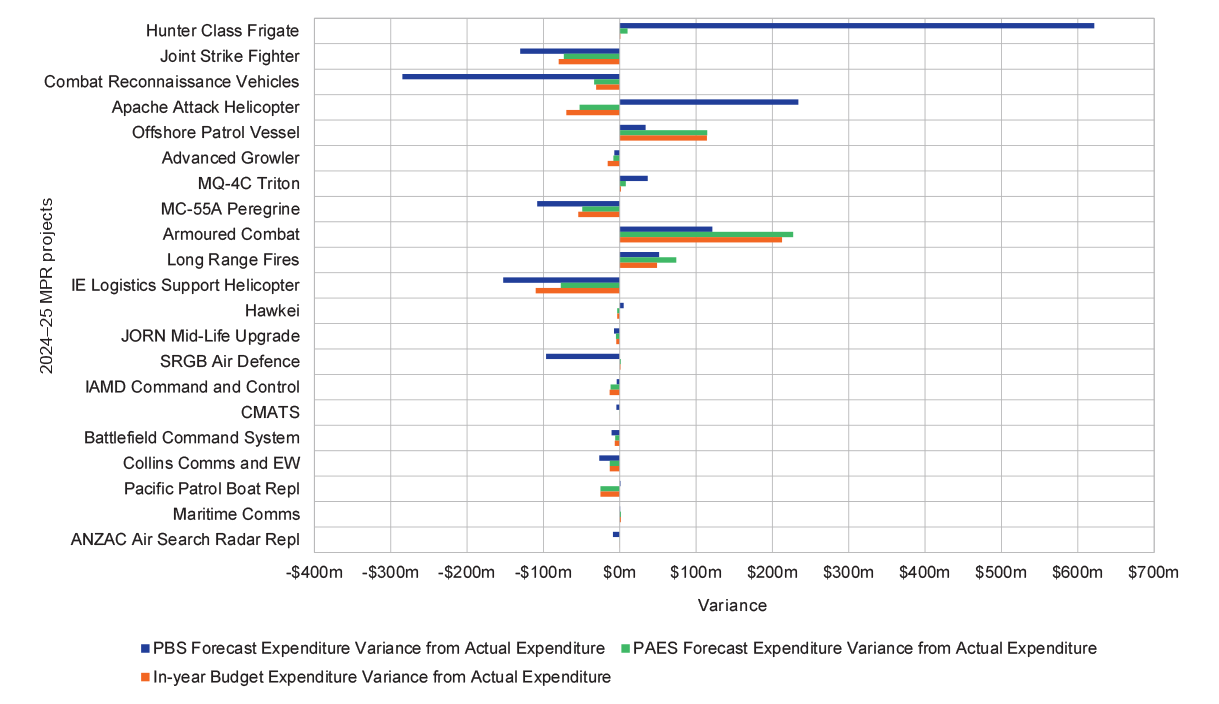

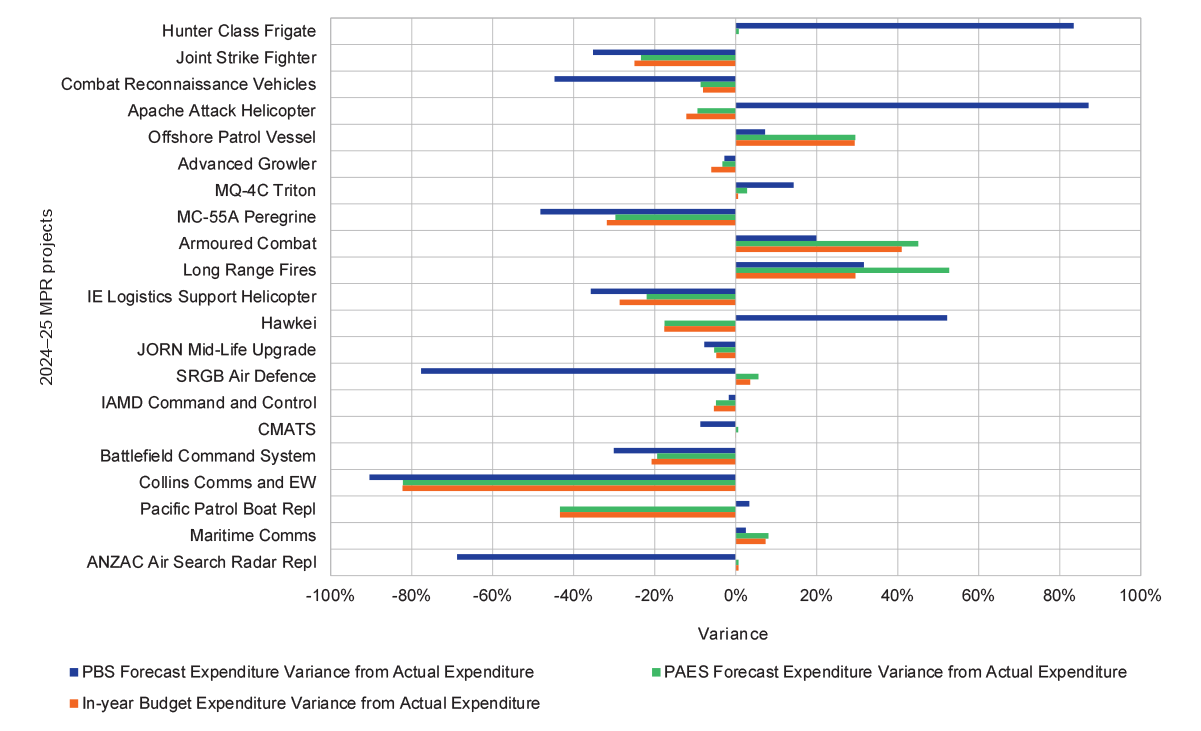

4.2 Analysis of the cost performance of the 21 projects includes: changes in budget since government second pass approval; total project expenditure by project and by domain; and forecast expenditure compared with actual expenditure.

4.3 Budget variations can include transfers of budget within Defence projects, additional funding from government approvals for scope changes, real cost increases, or administrative decisions. Budget variations since initial Second Pass Approval total $37,254.4 million. Of this, SEA5000 Hunter Class Frigate and AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B Joint Strike Fighter account for 80.9 per cent ($30,134.7 million) predominantly due to government approved changes in scope (an increase in 58 aircraft for AIR6000 and approval to commence construction of one to three ships for SEA5000) and exchange variations. Across all projects exchange variations contributes approximately $5,512.9 million. Table 4.1 sets out all budget variations for each project in the MPR as at 30 June 2025.

Table 4.1: Budget variations post government initial second pass approval by variation type as at 30 June 2025a

|

Project |

Budget at Second Pass Approval ($m)b |

Variation type |

Explanation of variation |

Year/s of variation |

Total variation ($m) |

|

SEA5000 Hunter Class Frigates |

6,183.9 |

Budget transfer/Government Second Pass Approval June 2024 (Batch 1 Construction) |

Funding transfers between CASG and other areas of Defence, and approval to commence construction of ships. |

2019–20 2021–22 2022–23 2023–24 |

19,661.6 |

|

LAND400 Phase 2 Combat Reconnaissance Vehicles |

5,762.7 |

Budget Transfer |

Funding transfer to enable Directorate of Land Training Capability to facilitate delivery of land simulation. |

2024–25 |

(4.5) |

|

AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B Joint Strike Fighter |

2,751.6 (Stage 1) |

Scope increase/Budgetary Adjustments/Transfer |

Government approval for 58 additional aircraft, and upgrades to air base facilities. |

2013–14 2017–18 2022–23 |

10,473.1 |

|

AIR5349 Phase 6 Advanced Growler |

271.1 |

Scope Increase/Transfer |

Next generation Jammer development and acquisition of aircraft upgrades, missiles and electronic warfare range upgrades and associated sustainment costs. Approval for facilities, offset by transfers between CASG and other areas of Defence. |

2019–20 2021–22 2022–23 |

2,878.4 |

|

AIR7001 MQ-4C Triton |

924.9 |

Scope increase/Budget Transfer/Real cost decrease/Budgetary adjustment |

Three additional aircraft across multiple approvals, and approval for initial sustainment funding. Minor transfers and budgetary adjustment. |

2017–18 2018–19 2019–20 2020–21 2021–22 2022–23 2023–24 2024–25 |

1,400.2 |

|

AIR555 MC-55A Peregrine |

2,166.3 |

Budgetary adjustment |

Minor transfers and corrections. |

2018–19 2021–22 2022–23 2023–24 2024–25 |

56.8 |

|

AIR2025 Phase 6 JORN Mid-Life Upgrade |

1,117.9 |

Scope increase/Budget Transfer/Budgetary adjustment |

Budgetary adjustment for High Power Amplifier Replacement Project. Other minor adjustments, transfers and scope increases. |

2020–21 2021–22 2022–23 2023–24 2024–25 |

132.6 |

|

LAND8113 Phase 1 Long Range Fires |

658.6 |

Scope Increase/Budgetary Adjustment |

Budgetary adjustment for estate components, and additional weapons systems. |

2023–24 2024–25 |

1,624.2 |

|

SEA9100 Phase 1 IE Logistics Support Helicopter |

1,460.2 |

Budget Transfer |

Budget transfer from AIR9000 Phase 8. |

2024–25 |

337.1 |

|

LAND19 Phase 7B SRGB Air Defence |

1,274.3 |

Budget Transfer |

Defence Science and Technology Group project closures and the transfer to Military Equipment Acquisition Projects. |

2024–25 |

0.6 |

|

AIR5431 Phase 3 CMATS |

731.4 |

Real Cost Increase/ Budgetary Adjustment/Budget Transfer |

Real cost increase and transfer of Air Force budget to the project, offset by minor transfers. |

2017–18 2021–22 2022–23 |

274.9 |

|

SEA1439 Phase 5B2 Collins Comms and EW |

247.7 (Stage 1) |

Scope Increase/Budgetary Adjustment |

Additional communications capability and minor budgetary adjustment. |

2016–17 2020–21 |

353.9 |

|

SEA3036 Phase 1 Pacific Patrol Boat Replacement |

504.5 |

Transfer |

Transfer of funding to NSSG for acquisition of three vessels. |

2023–24 2024–25 |

65.5 |

Note a: Some projects have multiple government second pass approvals. This table reports on variations since the first/initial Second Pass Approval. Projects that have had no Real Variations to their budget do not appear in this table. They were: Apache Attack Helicopter, Offshore Patrol Vessel, Armoured Combat, Hawkei, IAMD Command and Control, Battlefield Command System, Maritime Comms and ANZAC Air Search Radar Replacement. For a definition of ‘Real Variations’ see the 2024–25 MPR Guidelines in Part 4 of this report.

Note b: Budget at Second Pass Approval column is based off the initial Second Pass Approval of projects at the point of provision of the authority for a project to begin acquisition.

Source: ANAO analysis of 2024–25 PDSSs.

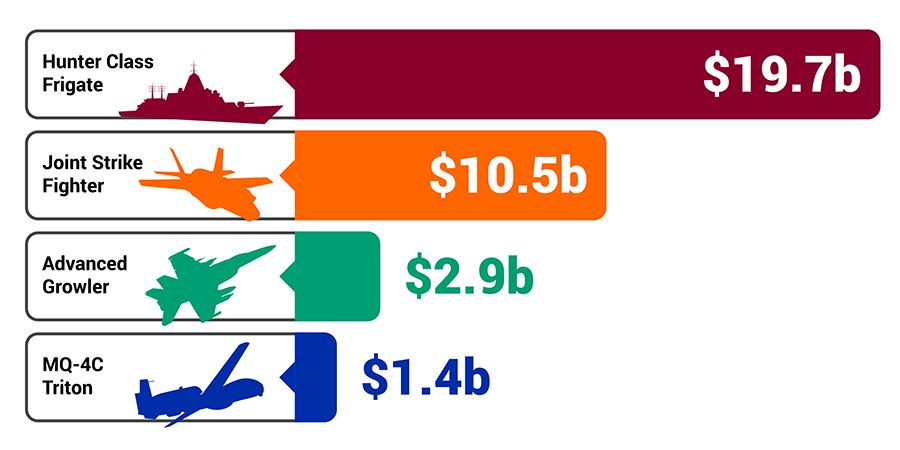

4.4 Real variations37 are a subset of all budget variations and primarily reflect changes to project scope, transfers between projects for approved equipment/capability, and budgetary adjustments such as administrative savings decisions. The two projects with the most significant real variations as at 30 June 2025 were:

- SEA5000 Hunter Class Frigate — $19,661.6 million for government second pass approval of construction of the first of three ships; and

- AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B Joint Strike Fighter — $10,473.1 million for Stage 2 government second pass approval of 58 additional aircraft.

4.5 The four projects with government approved scope increases valued at over $500 million ($0.5 billion) are set out in Figure 4.2

Figure 4.2: Projects with government approved scope increases over $0.5 billiona b c

Note a: Hunter Class Frigate – 2023–24: Second Pass Approval (Batch 1 Production); Joint Strike Fighter – 2013–14: 58 additional aircraft at Stage 2 Second Pass Approval; Advanced Growler - 2019–20: Government Interim Pass Approval ($0.3b); and 2022–23: Second Pass Approval for Tranche 1 ($2.6b); MQ-4C Triton - 2019–20: Second Pass Approvals Tranche 2 and 3 ($0.9b); 2020–21: Second Pass Approval Tranche 4 ($0.2b); and 2022–23: Subsequent Government Approval ($0.3b).

Note b: There are other scope increases across PDSSs that do not meet the $0.5b threshold.

Note c: For projects with multiple Second Pass Approval, this chart shows variations from the initial approval.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2024–25 PDSSs and previously published Defence PDSSs.

4.6 Exchange variations38 since government second pass approval across all 21 projects total $5,512.9 million. AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B Joint Strike Fighter accounts for 56.8 per cent ($3,132.4 million) of the total amount.

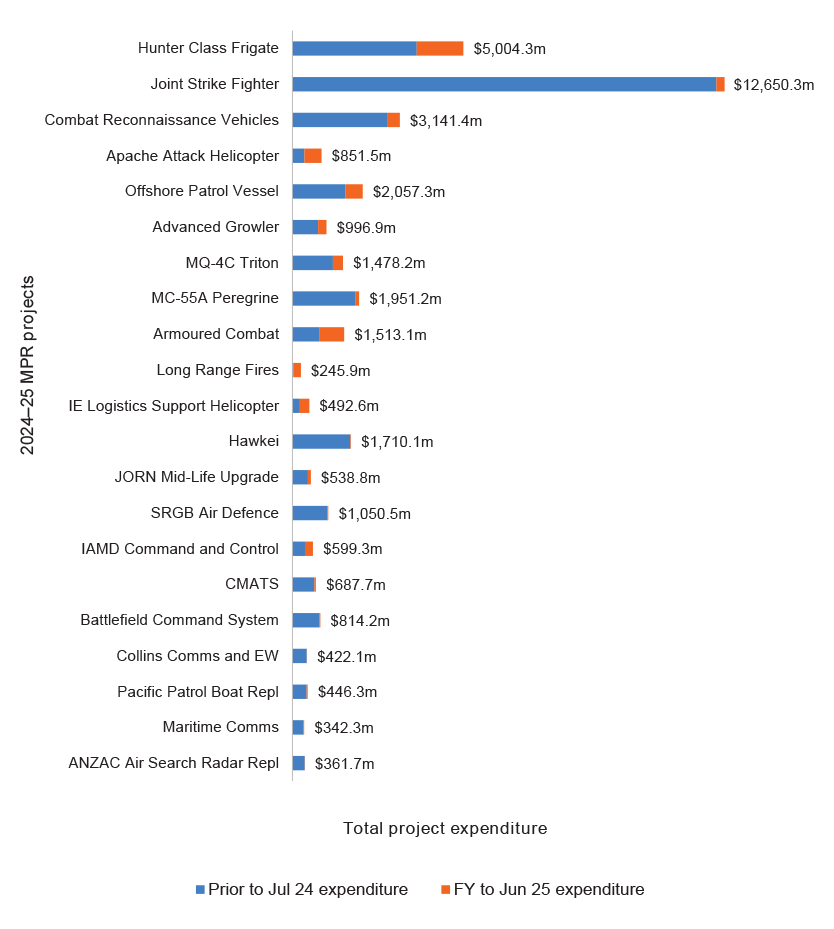

4.7 Figure 4.3 provides the total expenditure of the 21 MPR projects up to 30 June 2025, representing a total of $37,355.9 million. It also shows each project’s in-year expenditure for 2024–25 which is an indicator of milestone delivery and payments.

Figure 4.3: Total project expenditure as at 30 June 2025 ($m)

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2024–25 PDSSs.

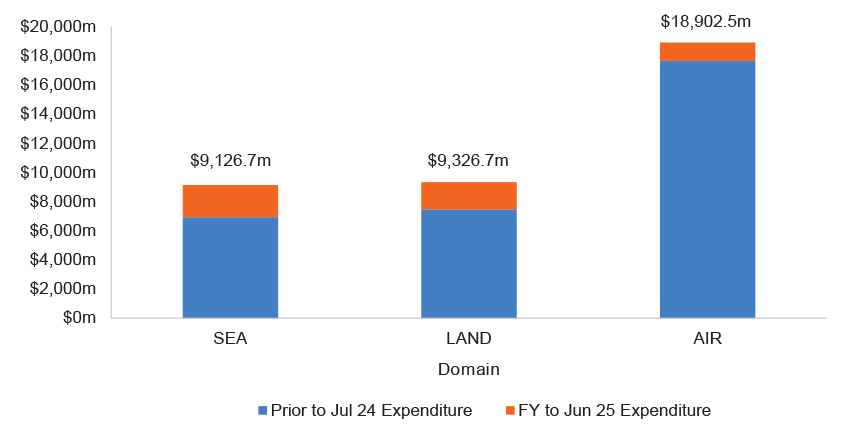

4.8 Figure 4.4 summarises the total project expenditure by domain, for the current year and for all years prior to July 2024, as reported in the 2024–25 PDSSs.

Figure 4.4: Total project expenditure by domain as at 30 June 2025 ($m)

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2024–25 PDSSs.

4.9 The total expenditure for AIR domain projects is approximately double that of each of the two other domains (SEA and LAND), accounting for 51 per cent of the total expenditure for the 21 projects. This is largely driven by AIR6000 Phase 2A/2B Joint Strike Fighter, which has $16.7 billion total approved budget (including $10.5 billion due to scope increase, see Figure 4.2). This contributed to 67 per cent of the total expenditure accrued by the AIR domain and 34 per cent of the total expenditure across all projects.

4.10 The SEA domain accounts for 24 per cent and the LAND domain accounts for 25 per cent of total expenditure accrued across all projects.