Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Currently showing reports relevant to the Education and Employment Senate estimates committee. [Remove filter]

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Australian Public Service (APS) employees have an obligation to comply with the Australian Government sector ethical framework and behave with integrity. The Australian Government sector ethical framework is defined by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) as the application of legislation and rules including the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule), Public Service Act 1999 (PS Act) and the APS Commissioner’s Directions 2022 (Commissioner’s Directions).

2. The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (DEWR) was established on 1 July 2022 as a result of machinery of government changes. DEWR’s 2024–25 Corporate Plan states that its purpose is to ‘support people in Australia to have safe, secure and well-paid work with the skills for a sustainable future’. DEWR is responsible for administering programs relating to training and employment, workplace relations, and work health and safety.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. All members of the APS are subject to ethical obligations established by legislation, specifically the PGPA Act, the PGPA Rule, the PS Act, and the Commissioner’s Directions. This audit will provide assurance to the Parliament on the effectiveness of DEWR’s approach to implementation of the Australian Government sector ethical framework.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of the implementation of frameworks to support ethical behaviours within DEWR.

5. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO applied the following high-level criteria.

- Do the ‘tone from the top’ and overarching strategies and policies within DEWR promote ethical behaviour and facilitate compliance with the Australian Government sector ethical framework?

- Are there appropriate supporting mechanisms in place to implement the ethical strategies and policies?

- Is there monitoring and reporting to provide assurance to the accountable authority that the strategies and policies are being implemented effectively?

Conclusion

6. DEWR has implemented largely effective enterprise-wide strategies and frameworks that have the potential to support its staff to comply with the Australian Government sector ethical framework. Effectiveness could be improved by ensuring its strategies and frameworks are measurable in terms of impact and establishing baselines and metrics for integrity-related reporting including across the delivery of its business.

7. DEWR’s tone from the top and overarching strategies and frameworks are largely effective in promoting ethical behaviour by DEWR staff and compliance with the Australian Government sector ethical framework. DEWR has messaging in place within its Corporate Plan 2024–25 to set the tone from top regarding expectations for DEWR leaders and staff to act with integrity. DEWR’s Integrity Framework 2024 provides guidance to all DEWR staff on integrity principles and sets out the resources available to assist staff to comply with the Australian Government sector ethical framework. DEWR’s People Strategy 2024–27 contains elements which reference the Australian Public Service (APS) Values and set expectations for DEWR’s leaders. DEWR has not developed a method for assessing the impact of the Integrity Framework and People Strategy in contributing to an ethical culture within DEWR, including when implementing its programs and measures. The DEWR executive provides regular communications to staff on matters relating to acting with integrity.

8. DEWR has largely appropriate mechanisms to implement its overarching ethical strategies and policies. These include: Accountable Authority Instructions (AAIs); the annual management assurance process; conflicts of interest processes; complaints and investigations mechanisms; fraud and corruption controls; credit card use policy; procurement and probity procedures; grants management guidance; gifts benefits and hospitality procedures; staff surveys; mandatory training; and Senior Executive Service (SES) performance management. Guidance and policy documents for these mechanisms sets out roles and responsibilities, oversight and reporting timeframes to DEWR’s governance committees. Where relevant, processes for non-compliance were identified in the process documentation. Assurance and oversight primarily occurs through reporting to DEWR’s governance forums.

9. Assurance on implementation of ethical strategies and supporting mechanisms is provided to DEWR’s Secretary through reporting to the Executive Board, the Audit and Risk Committee, the People, Culture and Engagement Committee and the Risk Committee. Instances of discussions relating to ethics, integrity, values or culture have increased across those forums since 2023. DEWR is developing a method to capture and report on key integrity-related matters in an Integrity Dashboard which it is planning to provide to the Executive Board. The dashboard focuses on information relating to financial management and performance under the requirements set out by the PGPA Act and the PS Act. DEWR has not set any baselines or metrics for relevant data sets in the dashboard, for example, rates of credit card non-compliance or mandatory training, which would enable performance over time to be monitored

Supporting findings

Ethical strategies and policies

10. DEWR’s purpose in its Corporate Plan sets its overall strategic direction and the Secretary’s messaging in the introduction to the Corporate Plan sets the tone for DEWR’s senior leaders (see paragraphs 2.3 to 2.6).

11. DEWR’s Integrity Framework was launched in June 2024 and sets out DEWR’s approach to building an integrity culture, including assigning roles and responsibilities and identifying guidance and procedures that contribute to driving integrity within the department. In October 2024 DEWR launched the People Strategy 2024–27 which incorporates an ethical leadership element aligned with the APS Values, sets out the expectations for DEWR leaders at all levels, and defines the priorities for its people and culture. DEWR has not developed an approach to ascertain the effectiveness of the implementation of the People Strategy or Integrity Framework (see paragraphs 2.7 to 2.45).

12. DEWR uses various communications to update staff on important information including: all staff emails; video messages from the Secretary and other Senior Executive Service (SES) officials; and weekly email updates. Within these communications, there are regular occurrences of staff being advised of their obligations around undertaking their roles ethically and with integrity, for example, reminders on fraud awareness training and embodying the APS Values. DEWR also communicated the launch of the Integrity Framework and training to all staff (see paragraphs 2.46 to 2.55).

Implementation mechanisms

13. DEWR has mechanisms in place to encourage ethical behaviour by its staff, facilitate compliance with Australian Government sector ethical framework, and identify and address areas of non-compliance. Processes and roles and responsibilities are set out in the supporting guidance for the mechanisms, including requirements around quality assurance and reporting to DEWR’s governance committees. Assurance and oversight are primarily provided through regular reporting to the DEWR executive and other governance forums. DEWR undertakes assurance activities within the processes for credit cards, fraud and corruption, code of conduct and SES personal declarations of interest. Non-compliance is managed for code of conduct, fraud investigations, credit card use and gifts and benefits. For these mechanisms, DEWR has procedures in place to manage non-compliance through avenues such as formal investigation, additional training, official warning or sanctions (see paragraphs 3.2 to 3.117).

Assessment, monitoring and reporting

14. DEWR has processes in place to enable monitoring and reporting on the progress and implementation of mechanisms that support DEWR’s implementation of the Australian Government sector ethical framework. DEWR is developing an Integrity Dashboard which intends to collate integrity-related data into the one report. DEWR has yet to develop metrics and baselines for the relevant data sets in the dashboard, or report on organisational integrity in delivering its programs and measures. DEWR’s Executive Board, Audit and Risk Committee, People, Culture and Engagement Committee and the Risk Committee regularly discussed matters relating to ethics, integrity, values or culture between 1 July 2022 and 31 December 2024. There has been an increase in the level of discussion of these themes in the forums since mid-2023 (see paragraphs 4.2 to 4.32).

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.32

The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations develops an approach to measure the effectiveness of the implementation of the Integrity Framework or People Strategy including how they support integrity in the administration of DEWR’s measures and programs.

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 4.25

The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations:

- establishes metrics and baselines for the relevant data sets in the Integrity Dashboard to enable compliance and performance to be tracked and reported over time;

- examines whether the dashboard (or other reporting) could be expanded to include broader assurance that ethical frameworks and mechanisms are being implemented in the administration of DEWR’s measures and programs.

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

15. The proposed audit report was provided to DEWR. DEWR’s summary response is provided below, and its full response is included in Appendix 1.

The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (the department) welcomes the audit’s recommendations and the recognition that the department has largely effective:

- strategies and frameworks, that have the potential to support its staff to comply with the Australian Government sector ethical framework

- promotional mechanisms in place, including tone from the top. This has included the department’s executive issuing regular communication on ethical matters

- mechanisms to support the implementation of ethical strategies and policies, including the People Strategy and the Integrity Framework

The department has agreed to both recommendations made by the ANAO; recognising the importance of fostering a strong ethical culture and maintaining robust integrity frameworks across all levels of the organisation. The department remains committed to embedding integrity into all aspects of our culture and recognises the importance of continuous improvement, ensuring frameworks also support integrity in the administration of departmental programs and measures.

The department is committed to ethical leadership at all levels, promoting an environment of accountability, where public officials act with probity and integrity. The department will continue to operate with transparency, designing and administering programs, policies and processes with a continual focus on the people they are meant to serve.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

16. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Child Care Subsidy (CCS) is administered by the Department of Education (Education) under the Family Assistance Law (FAL), to assist families to meet the cost of early childhood education and care.

2. At a cost of $13.6 billion in 2023–24, CCS is one of the ‘fastest-growing major payments’ of the Australian Government, with forecast average annual growth of 5.5 per cent over 2024–25 to 2034–35. As of September 2024, CCS supported 1.45 million children to attend approved care. This equates to 32.6 per cent of all 0 to 13-year-olds in Australia.

3. Education has policy responsibility for the CCS, including the CCS special appropriation. Services Australia is accountable for delivering payment and ICT services on behalf of Education, and for prioritising the service delivery within its budget appropriation.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. The CCS was estimated to be one of the top 20 expense programs in 2024–25. Australian Government spending on CCS was $13.6 billion in 2023–24, of which an estimated 3.6 per cent ($484.1 million) was lost to incorrect payments, including fraud and non-compliance. Fraud and non-compliance reduces available funds for public goods and services.

5. This audit was conducted to provide assurance to the Parliament over the effectiveness of the management and oversight of compliance activities within the Child Care Subsidy program. This audit was identified as a priority by the Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit in the context of the ANAO’s 2023–24 Annual Audit Work Program.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the management and oversight of compliance activities within the CCS program.

7. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level audit criteria were adopted:

- Have effective governance arrangements been established?

- Is the approach to compliance activities effective?

Conclusion

8. The management and oversight of compliance activities within the CCS is partly effective. Governance arrangements do not provide Education with whole of program oversight, and evaluation arrangements are only partly implemented. Although the payment accuracy rate improved in 2022–23 and 2023–24, and comprehensive prevention activities are in place, gaps in monitoring and enforcement are not being effectively managed.

9. Education has established partly effective arrangements to oversee CCS compliance activities. Committees accountable to a Senior Executive Service (SES) Band 2 within Education oversee its Child Care Subsidy Financial Integrity Strategy 2023–2027 (Integrity Strategy), which sets out its approach to risk based and data driven regulation of CCS providers and services, to be implemented from 2023 to 2027. To successfully complete its implementation of the Integrity Strategy, Education will need to improve its data quality in the Child Care Intelligence System (CCIS) and implement evaluation arrangements across the full suite of its compliance interventions.

10. Bilateral arrangements between Education and Services Australia are set out in a Statement of Intent and Program Delivery Services Schedule for Child Care Subsidy Program, which detail the objectives, governance, risk and issue management, roles and responsibilities and assurance obligations for CCS services. These arrangements do not provide Education with sufficient oversight of CCS compliance activities within Services Australia. Education has established a CCS Fraud and Corruption Risk Assessment (FCRA), but this is not supported by engagement with Services Australia over shared risks. Services Australia has not established a FCRA that includes CCS.

11. Education and Services Australia have established a partly effective approach to compliance activities. While Education and Services Australia have comprehensive arrangements to prevent non-compliance among providers and families respectively, deficiencies were identified in relation to monitoring, investigations and enforcement.

12. Services Australia is responsible for monitoring family compliance. It does not monitor non-employment activities, is unable to identify CCS-related matters within its tip-off data, and its income monitoring via the CCS reconciliation process is not consistent with the FAL, due to its reliance on lodged tax return data before a notice of assessment has been issued.

13. Education is responsible for monitoring provider compliance, and investigations and enforcement. It monitors whether providers continue to meet some conditions to administer CCS. It does not have assurance that all conditions are met, does not apply quality assurance across all monitoring and investigation activities, and does not investigate possible CCS provider overpayments identified while monitoring payment accuracy via the Random Sample Parent Check (RSPC). Its ability to effectively implement the Integrity Strategy is undermined by poor data quality in CCIS and a lack of cohesive enforcement strategy, which mean it is not able to assess whether decisions to take enforcement action are fair, impartial, consistent, or proportional.

Supporting findings

Governance arrangements

14. Education oversees CCS compliance activities via a Financial Integrity Governance Board (FIGB) and Financial Integrity Operational Committee (FIOC), that are accountable to the responsible SES Band 2. Education does not have visibility of compliance activities or risk management in Services Australia. Bilateral arrangements between the Department of Education and Services Australia are set out in a Statement of Intent between the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Services Australia and the Secretary of the Department of Education (Education Secretary). Under the Statement of Intent, the Program Delivery Services Schedule for Child Care Subsidy Program details the objectives, governance, risk and issue management, roles and responsibilities and assurance obligations for CCS services. These do not provide sufficient oversight of CCS compliance activities. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.26)

15. Education’s Integrity Strategy documents its approach to risk based and data driven regulation to be implemented from 2023 to 2027. To successfully complete its implementation of the Integrity Strategy, Education will need to improve its CCIS data quality. Although Services Australia’s annual CCS risk management plans document its approach to managing risk in the program, including compliance risk, there is no documented approach (either in Education’s Integrity Strategy or via Services Australia’s own program documentation) that provides strategic direction or describes how risk and data inform decision-making regarding Services Australia’s CCS compliance activities. Education has established a CCS FCRA, although information about the purpose, implementation status, and timeframes of risk treatments is not included. Risk identification, analysis and evaluation within the FCRA is not supported by engagement with Services Australia over shared risks. Services Australia has not established a FCRA that includes CCS. (See paragraphs 2.31 to 2.52)

16. Education monitors the effectiveness of the Integrity Strategy using payment accuracy data drawn from the RSPC and reporting against budget savings measures. As of March 2025, evaluations of compliance interventions have been planned but not yet implemented across the full suite of compliance interventions. Initial intervention evaluations and resulting adjustments for each team are due to be completed in 2025. As such, is not possible to effectively measure the impact of activities undertaken under the Integrity Strategy, or understand the relative contributions of different types of activities. (See paragraphs 2.53 to 2.70)

Approach to compliance activities

17. CCS program design, including the legislative framework administered by Education, has been strengthened to support compliance. Access to the program is managed via provider and individual application processes by Education and Services Australia respectively. Both entities provide appropriate information to stakeholders via a range of sector guidance, communications and advice. Education engages regularly with sector representatives and has commenced work to improve the capability of Family Day Care (FDC) providers to comply with their obligations under the FAL. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.19)

18. Education and Services Australia monitor family and provider compliance with the FAL using family income, sessions of care information from providers, electronic funder transfer (EFT) provider audits, and manual checking of provider reporting. These controls focus on incorrect session reporting resulting in incorrect payment. Education does not have assurance that certain other requirements, such as fit and proper person requirements, are met after initial CCS approval has been granted. Where non-compliance is suspected, Education may choose to conduct an administrative or criminal investigation. Services Australia’s use of data for checking family income is not consistent with the FAL, and there are deficiencies in Education’s record keeping, monitoring of ongoing provider and service eligibility for CCS, and quality assurance arrangements in both EFT provider audits and investigations. Services Australia’s collection of tip-off information does not effectively support the identification of CCS matters. (See paragraphs 3.22 to 3.62)

19. Education imposes fines, debts, conditions on approval, suspension and cancellation of approval, and refers matters for criminal prosecution as part of its work to enforce compliance with the FAL. Education does not have a policy to guide decisions on whether, and in what circumstances, to take enforcement action, and enforcement strategy has not been considered by the FIGB. Without cohesive policy guidance for staff, Education is unable to assess whether decisions to take enforcement action are fair, impartial, consistent, or proportional. From 2022–23 to 2023–24, across the CCS, Education withdrew $473,010 (42.2 per cent of the total $1.1 million) of fines issued, raised and recovered 11 compliance-related debts valued at $59,648 (0.9 per cent of the total $6.4 million) and identified but did not investigate 970 potential overpayments with a total value of $106,375. (See paragraphs 3.63 to 3.80)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.22

The Department of Education and Services Australia review and revise arrangements giving effect to the Statement of Intent and subordinate documents to ensure sufficient oversight of shared regulatory activities is provided.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Services Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.62

The Department of Education strengthen its approach to implementing evaluation of the effectiveness of compliance interventions, to cover all interventions in the Child Care Subsidy Financial Integrity Strategy 2023–2027.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.68

The Department of Education, in consultation with Services Australia:

- develop a program-level CCS compliance and enforcement strategy including:

- approaches to coordination;

- governance;

- risk management;

- reporting between the entities;

- reporting of savings outcomes against targets; and

- performance and impact measurement, review and evaluation.

- ensure a version of the strategy is published on each entity’s website.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Services Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.28

Services Australia work with the Department of Education to review and revise its arrangements for collecting and reporting information about Child Care Subsidy compliance-related matters, including tip-offs, risk assessments and controls, and investigations, to ensure sufficient information is provided to the Department of Education to oversee compliance activities.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Services Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.61

The Department of Education review whether its electronic investigation management system (EIMS) is fit for purpose and enables staff undertaking compliance related work to meet all requirements of legislation.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.73

The Department of Education seek independent legal advice from the Australian Government Solicitor regarding its obligations (under the Family Assistance Law and other relevant legislation such as the Privacy Act 1988) in respect to possible Child Care Subsidy provider overpayments identified while monitoring payment accuracy using the Random Sample Parent Check.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 3.79

The Department of Education update operational policies and procedures to:

- improve compliance related record keeping;

- ensure quality assurance and review arrangements are in place across relevant teams; and

- establish program-level investigations and enforcement policies to support fair, well documented, consistent, and proportional decision-making, and conflict-of-interest management.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

20. The proposed audit report was provided to the Department of Education and Services Australia. The summary responses are reproduced below and the full responses are at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

Department of Education

The Department of Education (the department) acknowledges the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) performance audit on the management and oversight of compliance activities within the Child Care Subsidy (CCS) program.

The management and oversight of compliance activities plays an important role in ensuring the proper use of CCS and the achievement of program outcomes. In the 2023–24 financial year, the department’s integrity activities resulted in the highest accuracy rates in provider claims for CCS on record, exceeding the program target.

These are substantial achievements, testament to the department’s commitment to strong regulation of CCS approved providers and its obligations under the Resource Management Guide-128.

The department is progressing a large work program to strengthen and further mature the delivery of its CCS compliance activities under the CCS Financial Integrity Strategy 2023–27. The department agrees with the seven recommendations and will address these as part of its ongoing commitment to strengthen the management and oversight of CCS compliance activities.

Services Australia

Services Australia (the Agency) welcomes the ANAO report on Management and Oversight of Compliance Activities within the Child Care Subsidy (CCS) Program. The Agency notes the report findings, including that management and oversight of compliance activities within the CCS Program are partly effective.

The Agency’s focus is on efficiently and effectively delivering payments and services to the Australian community, and compliance and program integrity are important aspects of this work. The Agency’s strategies, performance measures, and governance arrangements are focussed on ensuring the right payment to the right person at the right time.

The Agency is committed to continually improving its internal and external governance arrangements, performance monitoring and reporting, compliance activities, and guidance and support to staff to ensure the integrity of the CCS Program.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

21. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Program design

Performance and impact measurement

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Reducing the disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous economic outcomes has been a longstanding goal of Australian governments. The National Agreement on Closing the Gap aims to strengthen economic participation and development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and their communities.1 Increasing opportunities for Indigenous economic participation has also been an area of interest for the Australian Parliament.2

2. The Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP) was established in 2015 with the objective ‘to stimulate Indigenous entrepreneurship, business and economic development, providing Indigenous Australians with more opportunities to participate in the economy’.3 One of three elements of the IPP are the mandatory minimum requirements (MMRs), which are targets for minimum Indigenous employment and/or supply use for Australian Government contracts valued from $7.5 million in certain specified industries.4 The National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) is responsible for administering the IPP, including the MMRs.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. The stated policy objective of the MMRs is to ‘ensure that Indigenous Australians gain skills and economic benefit from some of the larger pieces of work that the Commonwealth outsources, including in Remote Areas’.5 Compliance with the MMRs is mandatory for non-corporate Commonwealth entities. The MMRs were established in July 2015 and became binding on contractors from 1 July 2016.

4. Auditor-General Report No. 25 2019–20 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Participation Targets in Major Procurements was undertaken to provide assurance that the MMRs were being effectively administered and selected entities were complying with them.6 The audit concluded that while the MMRs were effectively designed, their administration had been undermined by ineffective implementation and monitoring by the policy owner and insufficient compliance by the selected entities.7 The audit made six recommendations to improve administration of and compliance with the MMRs, which were all agreed to.

5. Auditor-General reports identify risks to the successful delivery of government outcomes and provide recommendations to address them. The tabling in the Parliament of an agreed response to an Auditor-General recommendation is a formal commitment by the entity to implement the recommended action. Effective implementation of agreed Auditor-General recommendations demonstrates accountability to the Parliament and contributes to realising the full benefit of an audit.8

6. This audit examines whether the NIAA; Department of Defence (Defence); Department of Education (Education); Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (DEWR)9; Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs); and Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts (Infrastructure) have effectively implemented agreed recommendations from Auditor-General Report No. 25 2019–20. Entities’ implementation of agreed recommendations will help provide assurance to the Parliament about whether the MMRs are meeting the objective of stimulating Indigenous entrepreneurship, business and economic development and providing Indigenous Australians with opportunities to participate in the economy.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The audit objective was to assess whether selected entities effectively implemented agreed recommendations from Auditor-General Report No. 25 2019–20 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Participation Targets in Major Procurements.

8. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Did the NIAA implement recommendations related to the administration of the MMRs?

- Does the NIAA manage exemptions to the MMRs effectively?

- Did selected entities implement recommendations related to their compliance with the MMRs?

Conclusion

9. Almost five years after the recommendations were agreed to, entities had partly implemented recommendations from Auditor-General Report No. 25 2019–20 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Participation Targets in Major Procurements. Although the NIAA had improved guidance for entities and sought to increase MMR reporting compliance, a recommendation for the NIAA as the policy owner to implement an evaluation strategy was not completed. The NIAA has not demonstrated whether the MMRs are improving Indigenous economic participation. A risk related to the inappropriate use of exemptions was not managed. Recommendations intended to address the risk that reporting on MMR contracts is incomplete and inaccurate were partly implemented by audited entities. Reforms to the Indigenous Procurement Policy were announced in February 2025 without a clear understanding of the policy’s effectiveness.

10. The NIAA largely implemented two of three recommendations relating to its administration of the MMRs: to develop guidance on the MMRs for Australian Government entities and contractors; and to implement a strategy to increase MMR reporting compliance. The NIAA did not complete a third recommendation as it developed but did not implement an MMR evaluation strategy. Additional commitments made by the NIAA in response to two recommendations were not met.

11. Contracts subject to the MMRs may be exempted by entities for valid reasons established in the Indigenous Procurement Policy. The inappropriate use of exemptions impedes achievement of the Indigenous Procurement Policy’s objectives. The NIAA’s management of exemptions has been partly effective. Systems have been set up to allow potentially invalid exemptions. There is a lack of guidance and assurance over the appropriate use of exemptions.

12. Defence, Education and Home Affairs largely implemented the agreed recommendations relating to compliance with the MMRs. The NIAA, DEWR and Infrastructure partly implemented the agreed recommendations. The MMRs are relevant to the approach to market, tender evaluation, contract management, reporting and finalisation phases of a procurement. Compliance with the MMR requirements was higher in the approach to market, tender evaluation and contract management phases than in the reporting and finalisation phases. All entities could do more to ensure contractors’ compliance with MMR targets and to gain assurance over reported MMR performance.

Supporting findings

Administration of mandatory minimum requirements

13. Auditor-General Report No. 25 2019–20 recommended that the NIAA develop tailored guidance on managing the MMRs throughout the contract lifecycle in consultation with entities and contractors. The NIAA published updated guidance on managing the MMRs in July 2020, following stakeholder consultation. The guidance included complete information for nine of 14 topics identified as requiring additional guidance in Auditor-General Report No. 25 2019–20. Guidance included incomplete information on MMR exemptions, managing MMR performance reporting, and obtaining assurance over contractors’ MMR performance reporting. As at March 2025, guidance had not been updated since July 2020 despite changes to MMR reporting requirements. A commitment to publish guidance tailored for Indigenous businesses was not met. (See paragraphs 2.5 to 2.22)

14. Contractors must report on, and Australian Government entities must assess, performance in meeting agreed MMR targets. Auditor-General Report No. 25 2019–20 recommended that the NIAA implement a strategy to increase entity and contractor compliance with MMR reporting requirements to ensure information in the Indigenous Procurement Policy Reporting Solution (IPPRS) is complete. The NIAA planned and undertook activities aimed at increasing contractors’ compliance with MMR reporting requirements and entities’ management of reporting non-compliance. These included improvements to the IPPRS and monitoring reporting compliance in Australian Government portfolios. The NIAA closed the ANAO recommendation before planned changes to the IPPRS were implemented. As at February 2025, the IPPRS did not fully support contract managers to meet reporting requirements for all types of MMR contracts. User feedback indicated ongoing access and support issues. While reporting compliance increased between 2022 and 2024, as at June 2024, entities and contractors were not fully compliant with MMR reporting requirements and information in the IPPRS was incomplete. Reforms to the IPP announced by government in February 2025 included potentially increasing transparency of suppliers’ performance against MMR targets. (See paragraphs 2.23 to 2.32)

15. Auditor-General Report No. 25 2019–20 recommended that the NIAA implement an evaluation strategy for the MMRs that outlines an approach to measuring the impact of the policy on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment and business outcomes. Although an evaluation strategy for the MMRs was finalised, it was not implemented. The NIAA has not met requirements to review the effectiveness of a procurement-connected policy every five years. There is no performance monitoring and limited public reporting about the MMRs. (See paragraphs 2.33 to 2.54)

Exemptions from mandatory minimum requirements

16. Between July 2016 and September 2024, 63 per cent (valued at $69.3 billion) of all contracts recorded in the Indigenous Procurement Policy Reporting Solution (IPPRS) were exempted from the MRRs by relevant entities. The proportion of contracts exempted by entities from the MMRs has increased over time. The IPPRS has been set up by the NIAA to allow entities to record reasons for exemptions. The reason categories in the IPPRS mainly align with the Indigenous Procurement Policy, however include a category called ‘other’ that does not align. Of exempted contracts, 34 per cent (valued at $30.2 billion) used the exemption category ‘other’. The NIAA advised the ANAO that some contracts exempted for ‘other’ reasons were exempted because they are in practice non-compliant with the Indigenous Procurement Policy. Entities’ use of the ‘other’ exemption category for non-compliant contracts obscures the degree of non-compliance with the MMRs and is not appropriate. The NIAA does not provide complete guidance on the use of exemptions, or assurance over the legitimacy of exemptions. The NIAA has not considered the strategic implications of exemption usage for the achievement of policy objectives. (See paragraphs 3.1 to 3.13)

Compliance with mandatory minimum requirements

17. Auditor-General Report No. 25 2019–20 recommended that all audited entities review and update their procurement protocols to ensure procuring officers undertaking major procurements that trigger the MMRs comply with required steps in the procurement process.

- As at December 2024, all entities updated their procurement protocols for MMR requirements. One component of this was the development of detailed internal guidance. As at December 2024, Defence, Education, Home Affairs and Infrastructure’s guidance identified key MMR requirements for the approach to market to contract management phases of the procurement lifecycle. DEWR’s guidance and the NIAA’s internal guidance did not identify all key MMR requirements.

- Aside from Home Affairs, all entities’ contracts were largely compliant with the MMRs at the approach to market, tender evaluation and contract management phases of the procurement lifecycle. Home Affairs’ contracts was partly compliant. Defence’s compliance was poorer for contracts resulting from panel procurements.

- All audited entities could improve tender evaluation processes by including an IPPRS search on tenderers’ past MMR compliance.

- In summary: Defence, Education, and Infrastructure largely implemented the 2019–20 recommendation, and the NIAA and DEWR partly implemented it. Home Affairs’ guidance was appropriately updated, however it has not consistently ensured that procuring officers undertaking major procurements that trigger the MMRs comply in practice with the required steps. (See paragraphs 4.3 to 4.18)

18. Auditor-General Report No. 25 2019–20 recommended that all audited entities establish processes, or update existing processes, to ensure contract managers and contractors regularly use the IPP Reporting Solution (IPPRS) for MMR reporting.

- Defence, Education and Home Affairs’ internal guidance identified key IPPRS reporting requirements, while the NIAA, DEWR and Infrastructure’s internal guidance did not identify all key requirements.

- For a sample of contracts, the NIAA’s MMR reporting was timely and based on accurate IPPRS data. For the other five entities, there were issues with both timeliness and accuracy. None of the five entities consistently followed up on late contractor reporting.

- When a contract variation is published on AusTender, IPPRS data is not consistently updated. This means a contract may be identified as on track to meet the MMR target based on incorrect values or a contract may move to the finalisation step prematurely as the end date is inaccurate.

- In summary: Defence, Education and Home Affairs largely implemented the 2019–20 recommendation, and the NIAA, DEWR and Infrastructure partly implemented it. (See paragraphs 4.19 to 4.37)

19. Auditor-General Report No. 25 2019–20 recommended that after guidance has been provided by the policy owner, all audited entities establish appropriate controls and risk-based assurance activities for active MMR contracts.

- As the policy owner, the NIAA published guidance in July 2020 that has a short overview on how MMR performance information could be verified.

- All six entities established at least some controls and arrangements to gain assurance over contractors’ MMR performance reporting. Controls and arrangements were more developed in Education and Home Affairs.

- For a sample of contracts examined, none of the entities consistently undertook assurance activities to verify contractor performance reporting. Defence undertook the most assurance activity.

- In summary: all entities partly implemented the 2019–20 recommendation. (See paragraphs 4.38 to 4.59)

|

Effectiveness of the mandatory minimum requirements |

|

Based on MMR performance information reported by Australian Government entities and contractors, the number and value of MMR contracts have grown since the introduction of the Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP) in 2015. In 2016–17, 17 contracts with MMR targets for Indigenous employment and/or supply use were awarded, with a total value of $756.4 million. In 2023–24, 189 MMR contracts were awarded with a total value of $5.9 billion. Between 1 July 2016 and 30 September 2024, 870 MMR contracts were awarded by 52 Australian Government entities with a total value of $45.2 billion. Indigenous employment and/or supply use targets established under the MMR contracts were reported to be met for 72 per cent of completed MMR contracts.a The majority of MMR contracts were reported to be meeting established employment and supply use targets. These results, however, were based only on contracts where reporting was complete. As at June 2024, 28 per cent of MMR contracts in the reporting phase were not compliant with MMR reporting requirements. Reporting relies on contractor information, and entities largely had not undertaken activities to verify that MMR performance information was accurate. While the application of the MMRs is trending upwards, between July 2016 and September 2024, 1,475 contracts valued at $69.3 billion were ‘exempted’ by entities from the MMRs, often for reasons that are unclear. There is a lack of performance information and evaluation data that allows for the impact and outcomes of the IPP to be assessed. The NIAA’s public reporting on the IPP does not provide information on the MMRs’ effectiveness. It is unclear if the IPP’s objectives of stimulating Indigenous entrepreneurship, business and economic development, and providing Indigenous Australians with more opportunities to participate in the economy, are achieved. While the Indigenous business sector has grown since the introduction of the IPP, in November 2024 the Joint Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs highlighted limitations in available data on the economic contribution of the sector and the impact of policies to support Indigenous economic participation.b |

Note a: Based on 161 contracts where an assessment outcome was reported as at 30 September 2024.

Note b: Joint Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, Inquiry into economic self-determination and opportunities for First Nations Australians (2024), pp. 13–19, 39–40.

Recommendations

20. This report makes eight recommendations.

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.21

To support Australian Government entities and contractors to comply with the mandatory minimum requirements (MMRs), in consultation with entities and contractors, the National Indigenous Australians Agency review and update MMR guidance material to ensure that it:

- accurately reflects the current process for managing MMR reporting in the Indigenous Procurement Policy Reporting Solution and provides guidance on appropriate reporting timeframes;

- provides sufficient information to support entities to implement risk-based assurance activities for MMR contracts; and

- provides sufficient information for entities and contractors on suitable evidence to support performance reporting.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.45

The National Indigenous Australians Agency establish a process to ensure it meets Australian Government requirements placed on policy owners of procurement-connected policies, including reapplication for recognition as a procurement-connected policy.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.52

The National Indigenous Australians Agency:

- complete and publish an evaluation of the effectiveness of the mandatory minimum requirements in contributing to meeting the objectives of the Indigenous Procurement Policy; and

- develop mandatory minimum requirements performance measures to enable ongoing monitoring.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.11

To ensure exemptions are accurately recorded in the Indigenous Procurement Policy Reporting Solution, non-compliance with the Indigenous Procurement Policy can be appropriately identified, all applicable contracts are subject to the mandatory minimum requirements reporting and assessment process, and the Indigenous Procurement Policy is achieving its policy objectives, the National Indigenous Australians Agency:

- amend its protocols to ensure that it is not treating non-compliance with mandatory minimum requirements as an exemption or exclusion;

- consider what scenarios that are consistent with allowable exclusions and exceptions within the Indigenous Procurement Policy are not covered by existing categories in the Indigenous Procurement Policy Reporting Solution and therefore whether the ‘other’ category is still justified and required;

- when implementing recommendation 1, provide additional guidance to Australian Government entities on the use of exemption categories, which includes information on when it is appropriate to classify a contract as an ‘exemption’, and when it is appropriate and inappropriate to use the exemption category of ‘other’; and

- implement a risk-based assurance process to ensure that reported exemptions or exclusions are legitimate.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed to parts a–c, Not agreed to part d.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 4.7

The National Indigenous Australians Agency and Department of Employment and Workplace Relations update internal procurement guidance to better support procuring officers undertaking major procurements that trigger the mandatory minimum requirements to comply with required steps in the procurement process.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 4.16

Department of Home Affairs strengthen controls to ensure compliance with the mandatory minimum requirements at the approach to market, tender evaluation and contract management phases of major procurements.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 4.24

The National Indigenous Australians Agency; Department of Employment and Workplace Relations; and Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts establish, strengthen or update guidance to ensure contract managers and contractors appropriately use the Indigenous Procurement Policy Reporting Solution for mandatory minimum requirements reporting.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations response: Agreed.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 8

Paragraph 4.53

All audited entities meet their responsibility under the Indigenous Procurement Policy to establish or strengthen processes to ensure contract managers undertake appropriate activities to ensure contractors’ compliance with mandatory minimum requirements (MMR) targets and verify that reported MMR performance information is accurate.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations response: Agreed.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

21. Extracts of the proposed audit report were provided to the NIAA, Defence, Education, DEWR, Home Affairs and Infrastructure. Entities’ summary responses are provided below. Entities’ full responses are provided at Appendix 1.

National Indigenous Australians Agency

The National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) welcomes the findings of the audit.

The primary purpose of the Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP) is to stimulate Indigenous entrepreneurship, business and economic development, providing Indigenous Australians with more opportunities to participate in the economy. The Mandatory Minimum Requirements (MMR) are a key component of this policy.

Prior to the implementation of the policy in 2015, Indigenous businesses secured limited business from Commonwealth procurement. The policy has significantly increased the rate of purchasing from Indigenous businesses.

The NIAA is proud to take the lead on behalf of the Commonwealth in providing advice on how to best meet the requirements of the IPP. The NIAA provides advice to Commonwealth entities through its many publications and its dedicated IPP team. Within the resources available, the NIAA has also invested in providing ICT tools and support to assist Commonwealth entities with their responsibility to ensure accurate reporting on targets and MMRs.

As with all other elements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, it is the responsibility of each Commonwealth entity to meet the obligations of the IPP. The NIAA welcomes the ANAO’s recommendations on how it can improve the advice it provides to entities to meet their obligations.

Department of Defence

Defence welcomes the ANAO Audit Report assessing whether selected entities effectively implemented the agreed recommendations from Auditor-General Report No. 25 2019–20 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Participation Targets in Major Procurements.

Defence agrees to the recommendation directed at all audited entities to establish or strengthen processes to ensure contract managers undertake appropriate activities to ensure contractors’ compliance with the mandatory minimum requirements (MMR) targets and verify that reported MMR performance information is accurate.

As the Commonwealth’s largest procurer, Defence is proud of its significant commitment towards supporting the long-term growth and sustainability of the Indigenous business sector, and will continue working with the National Indigenous Australians Agency to improve the monitoring and reporting of the MMR targets.

Department of Education

The Department of Education welcomes this report. The report recognises the significant efforts the department has made to implement changes recommended by the ANAO’s performance audit of February 2020, however the department acknowledges the need to continue its efforts to strengthen its processes to ensure contract managers undertake appropriate activities to ensure contractors’ compliance with mandatory minimum requirements (MMR) targets and verify that reported MMR performance information is accurate.

Education is already making progress towards meeting the report’s recommendation, including working with contract managers to ensure that assurance activities are performed more consistently, and that contract managers regularly review and verify contractor reports. Education will continue to engage with departmental contract managers to ensure that MMR contracts are actioned in the IPPRS within the audit’s recommended timeframes.

Education notes the audit’s broader messages to all entities on the importance of strengthening procurement processes to ensure tenderers’ Indigenous Participation Plans are assessed and that assessments are appropriately documented. Education has added additional information to its intranet guidance on the process required when evaluating tender responses for MMR contracts, and its guides on approaching the market and evaluating and selecting suppliers. In addition, Education has updated its Evaluation Plan templates to include MMR requirements as part of the evaluation process, where applicable.

Education are regular participants in the Commonwealth Procurement and Contract Management Community of Practice and participate in networking opportunities across the Australian Public Service, including informal knowledge sharing across entities.

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations

The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (DEWR) acknowledges the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO) report detailing the outcomes of the follow up audit of Targets for minimum Indigenous employment or supply use in major Australian Government procurements.

DEWR is committed to delivering compliant procurement processes that deliver the expected business outcomes. This includes ensuring compliance with the Indigenous Procurement Policy and that our high value (as defined by the Indigenous Procurement Policy) contracts are properly managed and reported on. Starting from a low maturity level, we have been on a continuous journey of improvement since the Department’s creation in July 2022 (following a Machinery of Government change). We acknowledge and accept the ANAO’s findings and commit to implementing their recommendations as part of our broader procurement maturity program of work.

Department of Home Affairs

The Department of Home Affairs is committed to the implementation of the Government’s policy objective to drive growth in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses and employment.

The Department agrees with the two recommendations made by the Auditor-General aimed at improving the Department’s compliance with mandatory minimum requirements (MMR) of the Indigenous Procurement Policy throughout the procurement and contract management phases, and will strengthen its processes, guidance, reporting and assurance activities to achieve this.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts

The department supports the policy objectives of the Indigenous Procurement Policy and the achievement of the Mandatory Minimum Requirements (MMR) as a key element of the IPP. This follow up audit, which examined all five of the department’s procurements that triggered the MMR, has highlighted the need for further improvement in aspects of the department’s arrangements for meeting the MMR. The department is committed to making the necessary improvements to its processes.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

22. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Policy implementation

Procurement

Governance and risk management

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman (the OFWO) was established on 1 July 2009 as an independent statutory office created by the Fair Work Act 2009 (the Fair Work Act) to promote compliance with workplace relations through advice, education and, where necessary, enforcement.1

2. The OFWO regulates all businesses and workers covered by the Fair Work Act. This represents approximately one million employing businesses and around 13 million workers. In 2023–24 the OFWO reported that it recovered $473 million in unpaid wages and entitlements for nearly 160,000 employees, of which $333 million was recovered from the large corporates sector.2

3. The Fair Work Ombudsman is the accountable authority of the OFWO. The Minister for Employment and Workplace Relations sets government policies and objectives relevant to the OFWO in carrying out its statutory functions as a regulator.3 Since July 2022, there have been legislative amendments to the Fair Work Act, including changes to the protection and entitlements of employees and additional responsibilities and funding for the OFWO. This included the OFWO assuming responsibility for the regulation of the Fair Work Act for the commercial building and construction industry and the ability to investigate allegations related to the prohibition of workplace sexual harassment.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. The OFWO is the national workplace relations regulator. Its functions include promoting and monitoring compliance with workplace laws, inquiring into and investigating breaches of the Fair Work Act and taking appropriate enforcement action. Since July 2022, the OFWO has made changes to its approach and operations in response to: the expansion of the coverage of the Fair Work Act; implementation of the recommendations resulting from an external review; and revisions to its budget. This audit was conducted to provide assurance to Parliament that the OFWO is exercising its regulatory functions effectively.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman’s exercise of its regulatory functions.

6. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Has the OFWO established fit-for-purpose governance arrangements to support the effective management of compliance with the Fair Work Act?

- Are the OFWO’s arrangements to encourage voluntary compliance and detect non-compliance with the Fair Work Act effective?

- Are the OFWO’s arrangements to enforce compliance with the Fair Work Act effective?

Conclusion

7. The OFWO is largely effective in the exercise of its regulatory functions. There are opportunities for it to improve its effectiveness by improving strategic oversight of its regulatory objectives and outcomes, establishing frameworks for implementing and monitoring of regulatory priority areas and activities, and measuring the efficiency and effectiveness of its regulation.

8. The OFWO has established largely fit-for-purpose governance arrangements to support the effective management of compliance with the Fair Work Act. The OFWO developed compliance strategies that reflected ministerial Statements of Expectations. The compliance strategies were partly risk-based and not fully integrated into OFWO’s business planning. The OFWO is effective in managing its stakeholder relationships except for not assessing regulatory capture risk as a discrete source of risk. The OFWO’s monitoring of its regulatory performance focused on operational decision-making rather than the achievement of its regulatory priorities and outcomes. The OFWO is redeveloping its performance measures with the intention of improving its reporting of efficiency and effectiveness.

9. The OFWO’s arrangements to encourage voluntary compliance and detect non-compliance with the Fair Work Act are largely effective. The OFWO has established arrangements for the prevention, and proactive and reactive detection, of non-compliance and has published a compliance and enforcement policy. The OFWO does not monitor timeliness, risk, or return on investment for its prevention and detection of non-compliance. The OFWO does not have insight into whether the balance of preventative and detective compliance and enforcement activities is appropriate.

10. The OFWO’s arrangements to enforce compliance with the Fair Work Act are largely effective. The OFWO has established arrangements to manage non-compliance cases and the OFWO deploys its enforcement tools in line with its regulatory posture and policies. The OFWO’s monitoring and reporting does not provide an assessment of the effectiveness of its enforcement activities and outcomes in promoting compliance with the Fair Work Act. The OFWO compliance and enforcement actions were undertaken in accordance with internal policies. These actions were not adequately documented in OFWO’s records management systems. The OFWO documented that it would deviate from implementing the mandatory requirements of the Australian Government Investigations Standard, October 2022 (AGIS 2022). Deviations include not implementing a quality assurance framework.

Supporting findings

Governance arrangements

11. The OFWO’s approach to developing and implementing regulatory priorities and compliance strategies takes into consideration the requirements of the ministerial Statements of Expectations. The OFWO’s regulatory priorities and compliance strategies are not fully integrated into business planning and do not reflect a comprehensive assessment of risk exposures and mitigations. (See paragraphs 2.4 to 2.30)

12. The OFWO has established stakeholder engagement and management arrangements to support its regulatory functions. The OFWO has also established stakeholder feedback processes. The OFWO has not documented regulatory capture as a discrete source of risk or assessed the adequacy of its controls to mitigate regulatory capture risk. (See paragraphs 2.31 to 2.49)

13. The OFWO’s governance arrangements have a focus on operational decision-making. The enforcement board did not fully meet its terms of reference to provide strategic monitoring of regulatory activities. The OFWO’s performance reporting arrangements prior to 2024–25 included measures of output rather than efficiency and effectiveness. The OFWO is re-developing its performance measures and will need to provide greater insight into the ongoing effectiveness of its regulatory outcomes and impacts. (See paragraphs 2.50 to 2.84)

Prevention and detection of non-compliance

14. The OFWO has provided assistance, advice and education to employees, employers, outworkers, outworker entities and organisations to achieve regulatory objectives. The OFWO has developed and published a compliance and enforcement policy. The policy does not provide clear guidance to users about: how services will be prioritised and provided; and does not fully address the different needs of internal and external users. (See paragraphs 3.4 to 3.33)

15. The OFWO has established arrangements for proactive and reactive detection of non-compliance, including intelligence and analysis, proactive investigations, responding to requests for assistance, self-reporting of non-compliance and ad hoc investigations. These arrangements do not consider operational requirements and constraints, such as budgets, timeliness, risk and return on investment. This information would allow the OFWO to monitor the efficiency and effectiveness of its regulatory activities and assess whether the balance of preventative and detective activities is appropriate for the OFWO’s regulatory objectives. (See paragraphs 3.34 to 3.66)

Enforcement

16. The OFWO deploys its compliance and enforcement tools in line with its regulatory posture and compliance and enforcement policy. The use of compliance and enforcement tools requires long term management. Fifty per cent of investigations take more than 136 days to finalise with two per cent taking more than two years. The OFWO’s monitoring and reporting does not provide an assessment of the effectiveness of its enforcement activities and outcomes in promoting compliance with the Fair Work Act. (See paragraphs 4.2 to 4.17)

17. In July 2024, the OFWO assessed and agreed deviations from AGIS 2022. One ‘notable deviation’ from AGIS 2022 was the decision not to implement a quality assurance framework. Prior to July 2024, the OFWO did not use the relevant AGIS to inform the development of its policies, procedures, staff roles and staff qualifications. At November 2024, 50 per cent of OFWO staff conducting or oversighting investigations did not hold the relevant certification as required by AGIS 2022. The OFWO’s decision records did not evidence that compliance and enforcement activities were performed adequately. For example, case monitoring meeting and approvals were not consistently recorded in OFWO’s records management systems. (See paragraphs 4.18 to 4.55)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.29

The Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman delivers a framework for the implementation and monitoring of regulatory priority areas and activities that is integrated with business planning and is risk-based.

Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.63

The Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman ensures that governance bodies perform strategic oversight and monitoring of regulatory objectives and outcomes and consider the efficiency and effectiveness of regulatory activities.

Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 4.54

The Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman ensures that there is:

- documentation of the completion of mandatory steps set out in policies and procedures for investigations; and

- appropriate review and quality assurance of investigations to improve levels of compliance and to take corrective action where necessary.

Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

18. The proposed audit report was provided to the OFWO. The OFWO’s summary response is reproduced below and its full response is at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

The OFWO welcomes the ANAO’s report and agrees with the recommendations.

The OFWO has experienced considerable transformation over the past year. Central to the new strategic enforcement approach is tripartism, recognising that each element within the workplace relations system plays an important role in fostering a culture of compliance. As part of this, the OFWO has established a range of collaborative mechanisms with stakeholders and is updating critical strategic documents that define the Agency’s approach and operating environment.

A new organisational structure took effect on 1 July 2024 so that the OFWO is best positioned to deliver its identified objectives and strategic goals.

As detailed in our Statement of Intent, we use intelligence and data to inform our work, including the selection of our priority areas. We are committed to maintaining strong governance, supporting transparent and consistent decision-making.

As detailed in our Statement of Intent, we strive for continuous improvement in our policies, processes and practices. We are committed to focussing on developing the leadership and operational capability of staff at all levels, through our capability uplift program, to ensure we effectively discharge our statutory functions.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

19. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

Policy/program implementation

Executive summary

1. Performance information is important for public sector accountability and transparency as it shows how taxpayers’ money has been spent and what this spending has achieved. The development and use of performance information is integral to an entity’s strategic planning, budgeting, monitoring and evaluation processes.

2. Annual performance statements are expected to present a clear, balanced and meaningful account of how well an entity has performed against the expectations it set out in its corporate plan. They are an important way of showing the Parliament and the public how effectively Commonwealth entities have used public resources to achieve desired outcomes.

The needs of the Parliament

3. Section 5 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) sets out the objects of the Act, which include requiring Commonwealth entities to provide meaningful performance information to the Parliament and the public. The Replacement Explanatory Memorandum to the PGPA Bill 2013 stated that ‘The Parliament needs performance information that shows it how Commonwealth entities are performing.’1 The PGPA Act and the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) outline requirements for the quality of performance information, and for performance monitoring, evaluation and reporting.

4. The Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) has a particular focus on improving the reporting of performance by entities. In September 2023, the JCPAA tabled its Report 499, Inquiry into the Annual Performance Statements 2021–22, stating:

As the old saying goes, ‘what is measured matters’, and how agencies assess and report on their performance impacts quite directly on what they value and do for the public. Performance reporting is also a key requirement of government entities to provide transparency and accountability to Parliament and the public.2

5. Without effective performance reporting, there is a risk that trust and confidence in government could be lost (see paragraphs 1.3 to 1.6).

Entities need meaningful performance information

6. Having access to performance information enables entities to understand what is working and what needs improvement, to make evidence-based decisions and promote better use of public resources. Meaningful performance information and reporting is essential to good management and the effective stewardship of public resources.

7. It is in the public interest for an entity to provide appropriate and meaningful information on the actual results it achieved and the impact of the programs and services it has delivered. Ultimately, performance information helps a Commonwealth entity to demonstrate accountability and transparency for its performance and achievements against its purposes and intended results (see paragraphs 1.7 to 1.13).

The 2023–24 performance statements audit program

8. In 2023–24, the ANAO conducted audits of annual performance statements of 14 Commonwealth entities. This is an increase from 10 entities audited in 2022–23.

9. Commonwealth entities continue to improve their strategic planning and performance reporting. There was general improvement across each of the five categories the ANAO considers when assessing the performance reporting maturity of entities: leadership and culture; governance; reporting and records; data and systems; and capability.

10. The ANAO’s performance statements audit program demonstrates that mandatory annual performance statements audits encourage entities to invest in the processes, systems and capability needed to develop, monitor and report high quality performance information (see paragraphs 1.18 to 1.27).

Audit conclusions and additional matters

11. Overall, the results from the 2023–24 performance statements audits are mixed. Nine of the 14 auditees received an auditor’s report with an unmodified conclusion.3 Five received a modified audit conclusion identifying material areas where users could not rely on the performance statements, but the effect was not pervasive to the performance statements as a whole.

12. The two broad reasons behind the modified audit conclusions were:

- completeness of performance information — the performance statements were not complete and did not present a full, balanced and accurate picture of the entity’s performance as important information had been omitted; and

- insufficient evidence — the ANAO was unable to obtain enough appropriate evidence to form a reasonable basis for the audit conclusion on the entity’s performance statements.

13. Where appropriate, an auditor’s report may separately include an Emphasis of Matter paragraph. An Emphasis of Matter paragraph draws a reader’s attention to a matter in the performance statements that, in the auditor’s judgement, is important for readers to consider when interpreting the performance statements. Eight of the 14 auditees received an auditor’s report containing an Emphasis of Matter paragraph. An Emphasis of Matter paragraph does not modify the auditor’s conclusion (see Appendix 1).

Audit findings

14. A total of 66 findings were reported to entities at the end of the final phase of the 2023–24 performance statements audits. These comprised 23 significant, 23 moderate and 20 minor findings.

15. The significant and moderate findings fall under five themes:

- Accuracy and reliability — entities could not provide appropriate evidence that the reported information is reliable, accurate and free from bias.

- Usefulness — performance measures were not relevant, clear, reliable or aligned to the entity’s purposes or key activities. Consequently, they may not present meaningful insights into the entity’s performance or form a basis to support entity decision making.

- Preparation — entity preparation processes and practices for performance statements were not effective, including timeliness, record keeping and availability of supporting documentation.

- Completeness — performance statements did not present a full, balanced and accurate picture of the entity’s performance, including all relevant data and contextual information.

- Data — inadequate assurance over the completeness, integrity and accuracy of data, reflecting a lack of controls over how data is managed across the data lifecycle, from data collection through to reporting.

16. These themes are generated from the ANAO’s analysis of the 2023–24 audit findings, and no theme is necessarily more significant than another (see paragraphs 2.12 to 2.17).

Measuring and assessing performance

17. The PGPA Rule requires entities to specify targets for each performance measure where it is reasonably practicable to set a target.4 Clear, measurable targets make it easier to track progress towards expected results and provide a benchmark for measuring and assessing performance.

18. Overall, the 14 entities audited in 2023–24 reported against 385 performance targets in their annual performance statements. Entities reported that 237 targets were achieved/met5, 24 were substantially achieved/met, 24 were partially achieved/met and 82 were not achieved/met.6 Eighteen performance targets had no definitive result.7

19. Assessing entity performance involves more than simply reporting how many performance targets were achieved. An entity’s performance analysis and narrative is important to properly inform stakeholder conclusions about the entity’s performance (see paragraphs 2.37 to 2.44).

Connection to broader government policy initiatives

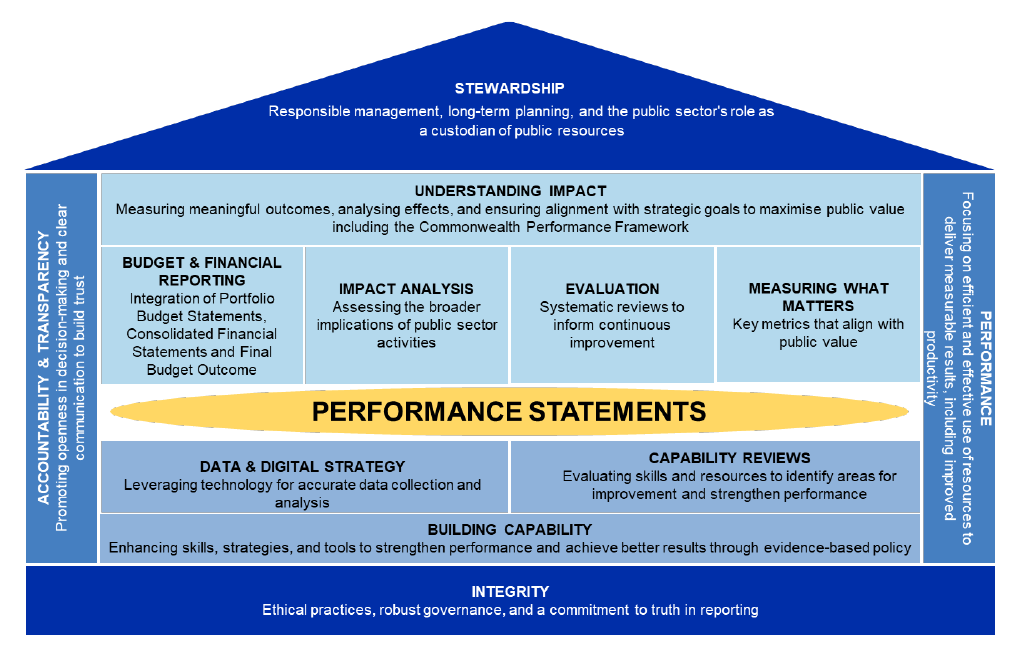

20. Performance statements audits touch many government policies and frameworks designed to enhance government efficiency, effectiveness and impact, and strengthen accountability and transparency. This is consistent with the drive to improve coherence across the Commonwealth Government’s legislative and policy frameworks that led to the PGPA Act being established.8 The relationship between performance statements audits and existing government policies and frameworks is illustrated in Figure S.1.

Figure S.1. Relationship of performance statements audits to government policies and frameworks

Source: ANAO analysis.

The future direction of annual performance statements audits

21. Public expectations and attitudes about public services are changing.9 Citizens not only want to be informed, but also to have a say between elections about choices affecting their community10 and be involved in the decision-making process, characterised by, among other things, citizen-centric and place-based approaches that involve citizens and communities in policy design and implementation.11 There is increasing pressure on Commonwealth entities from the Parliament and citizens demanding more responsible and accountable spending of public revenues and improved transparency in the reporting of results and outcomes.

22. A specific challenge for the ANAO is to ensure that performance statements audits influence entities to embrace performance reporting and shift away from a compliance approach with a focus on complying with minimum reporting requirements or meeting the minimum standard they think will satisfy the auditor.12 A compliance approach misses the opportunity to use performance information to learn from experience and improve the delivery of government policies, programs and services.