Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

2024–25 Performance Audit Outcomes

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

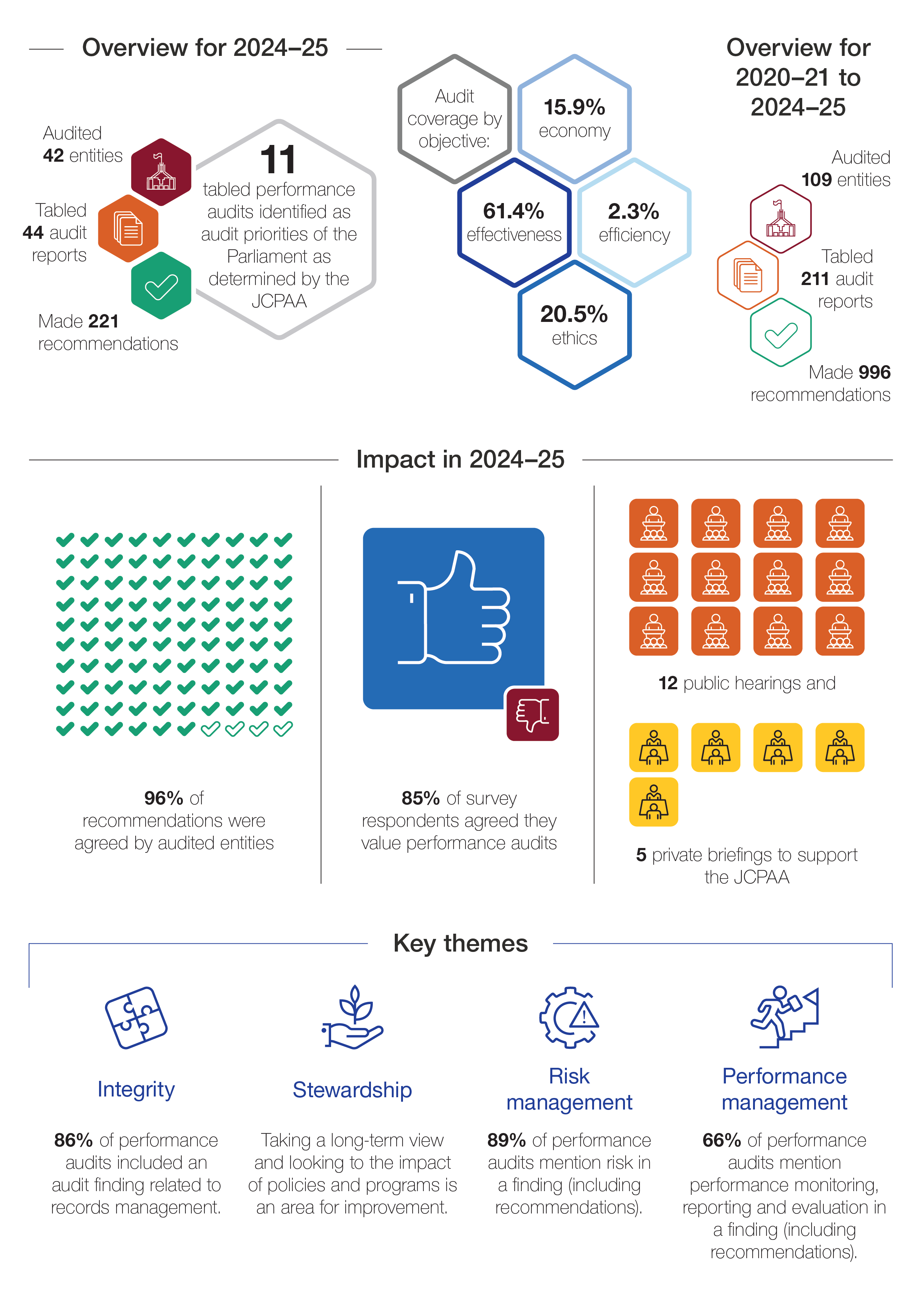

Snapshot: 2024–25 performance audit reports

Executive summary

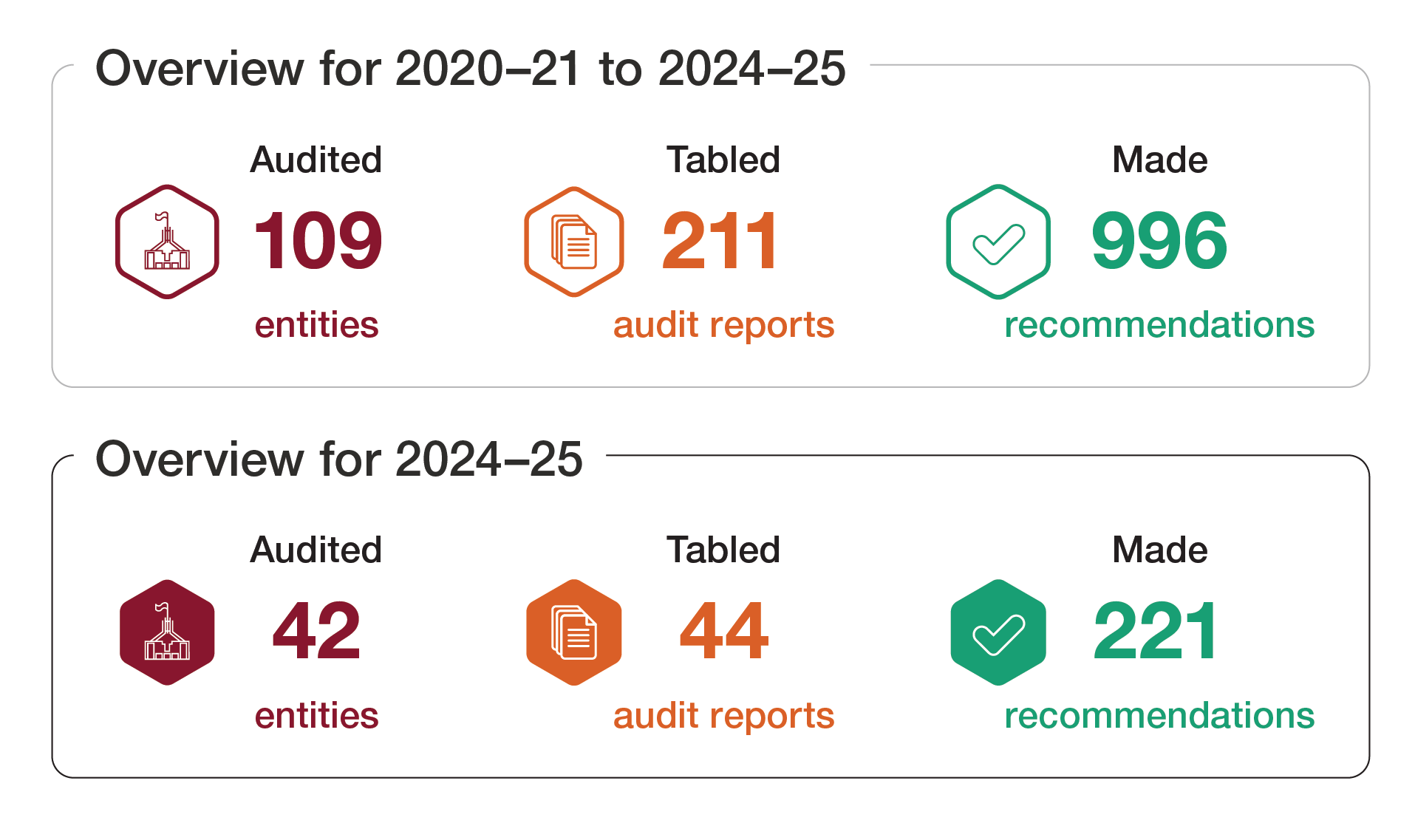

The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) conducted 44 performance audits across the 2024–25 financial year to provide independent and objective assessments of all or part of an entity’s operations. This report presents themes and insights from the 2024–25 performance audit program, as well as analysis of the outcomes of performance audits between 2020–21 and 2024–25.

Performance audits provide transparency, accountability and insights to the Parliament of Australia (Parliament), the Executive Government and the public on areas in which improvements can be made to public administration. Recommendations in performance audits assist entities to improve performance.

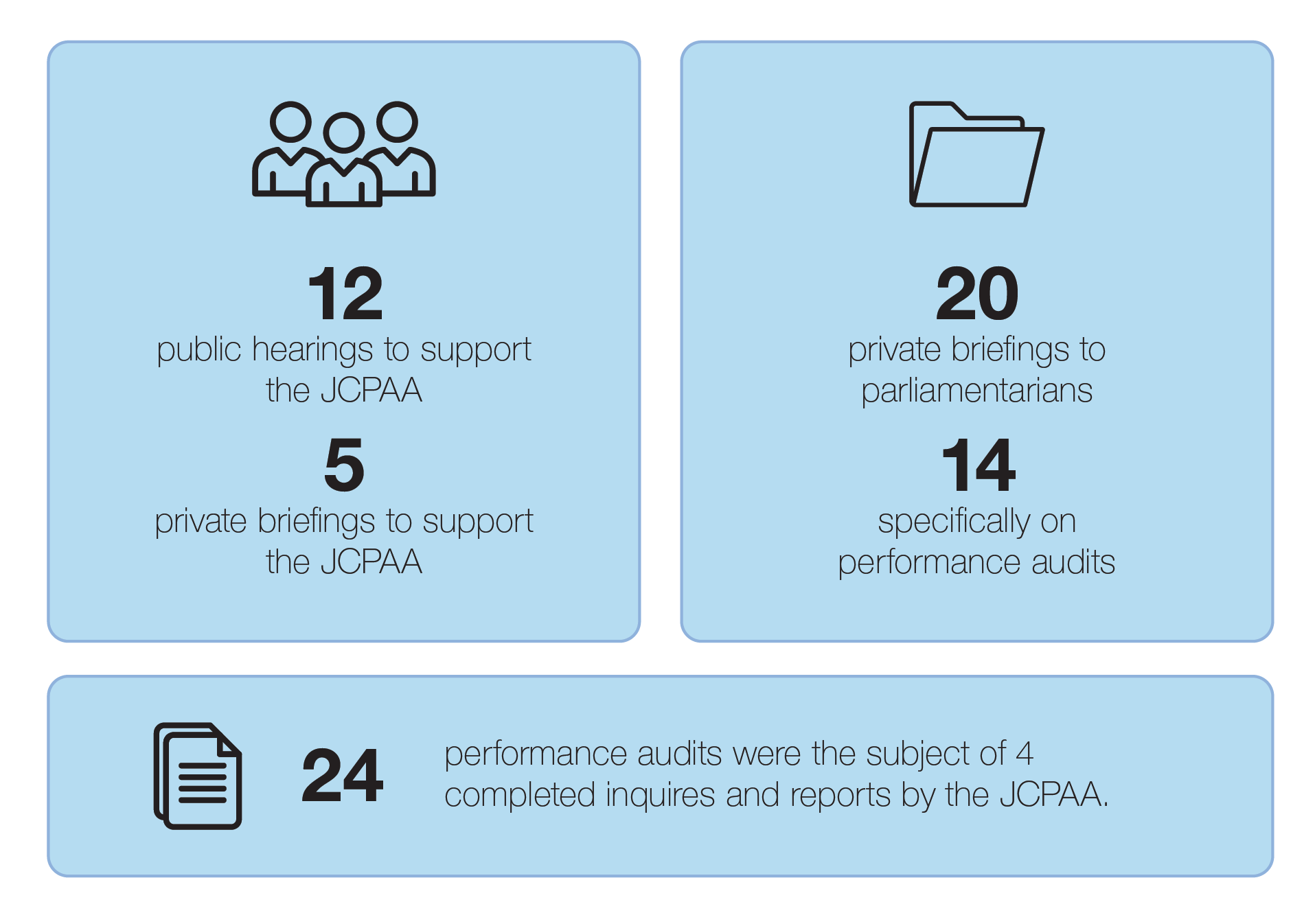

Performance audits undertaken in 2024–25 included topics drawn from both the 2023–24 and 2024–25 Annual Audit Work Programs and had regard to the priorities of the Parliament, as identified by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA). In 2024–25, the JCPAA completed four inquiries relating to 24 ANAO performance audit reports.

The 2024–25 program continued a focus on audits of integrity matters, including compliance with legislative and policy requirements, such as compliance with gifts, benefits and hospitality requirements, fraud control arrangements and management of conflicts of interest. These audits were aimed at assessing performance in broad areas of integrity, as the public sector continues to build stronger systems of integrity including through the implementation of the Louder Than Words: An APS Integrity Action Plan, and observing themes raised by the Commissioner of the National Anti-Corruption Commission.

The program also continued a series of audits on procurements by the Australian Government, including major Defence procurements, as well as Indigenous service delivery, grants management and entity governance.

Between 2020–21 and 2024–25, 54 per cent of audit conclusions were assessed as ‘positive’, indicating that entities were either unqualified (fully effective) or largely effective in delivering outcomes and complying with relevant frameworks. Audits of policy development showed the strongest overall performance, with 64 per cent of audits receiving ‘positive’ conclusions (‘unqualified’ or ‘largely effective’). In contrast, audits of grants administration and procurement recorded the highest share of ‘adverse’ conclusions, at 23 per cent and 19 per cent respectively. Notably, 55 per cent of grants administration audits resulted in ‘negative’ conclusions (for example, ‘adverse’ or ‘partly effective’).

Four key themes emerged from our performance audits: integrity; stewardship; risk management; and performance management. Audits have observed good practices as well as deficiencies, and examples of both are provided in this report.

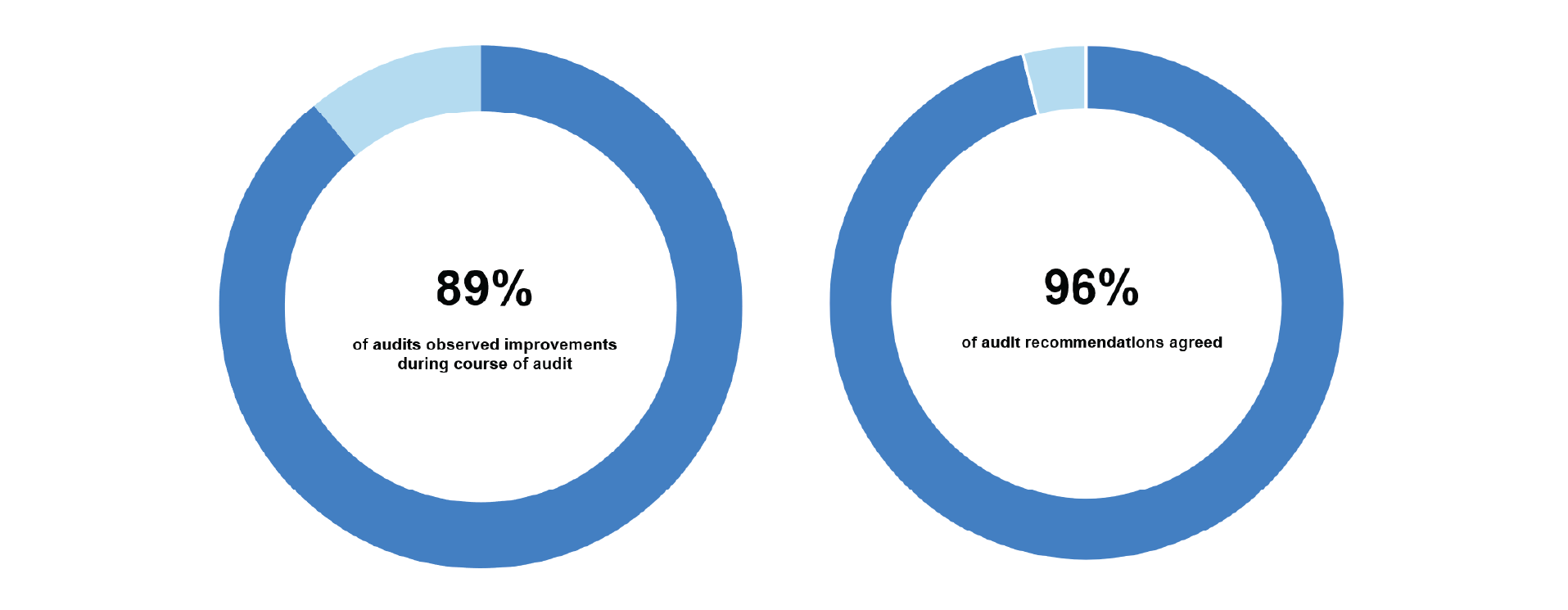

Performance audits have led to improvements in whole-of-government frameworks as well as in individual entities. Ninety-six per cent of the 2024–25 performance audit recommendations were agreed to by audited entities and 89 per cent of audits observed improvements during the audit. In this way, performance auditing is an invaluable tool to assist the Parliament in exercising its critical accountability functions and help the sector to drive performance improvement.

1. Introduction

1.1 To promote transparency, accountability and improved performance in the public sector, the Auditor-General undertakes performance audits, with reports tabled in the Parliament of Australia (Parliament). Performance audits involve the independent and objective assessment of all or part of an entity’s operations and administrative support systems, including the proper use of public resources.1 Performance audits may involve multiple entities and examine common aspects of administration or the joint administration of a program.

1.2 Drawing on insights from these performance audits, this information report2 presents a summary and analysis of outcomes from the 44 performance audits undertaken across the Australian Government sector and tabled in the Parliament during 2024–25. It highlights emerging key themes around integrity, stewardship, risk management, and performance management and includes a five-year longitudinal analysis of performance audit outcomes from 2020–21 to 2024–253 (see Appendix 1 for a full list of performance audits tabled in 2024–25).

1.3 This report complements other summary reports presented to the Parliament covering the operation of controls in material entities, and results of the programs covering financial statements audits and performance statements audits.4 This report is intended to assist the Parliament in understanding the results of the performance audit program and emerging and ongoing themes. It also aims to share insights more broadly across the public sector to support continuous improvement (see Appendix 2 for a list of 2024–25 Insights and Audit Matters publications).

Performance audits — independent assurance to the Parliament

Auditor-General’s role and relationship with the Parliament

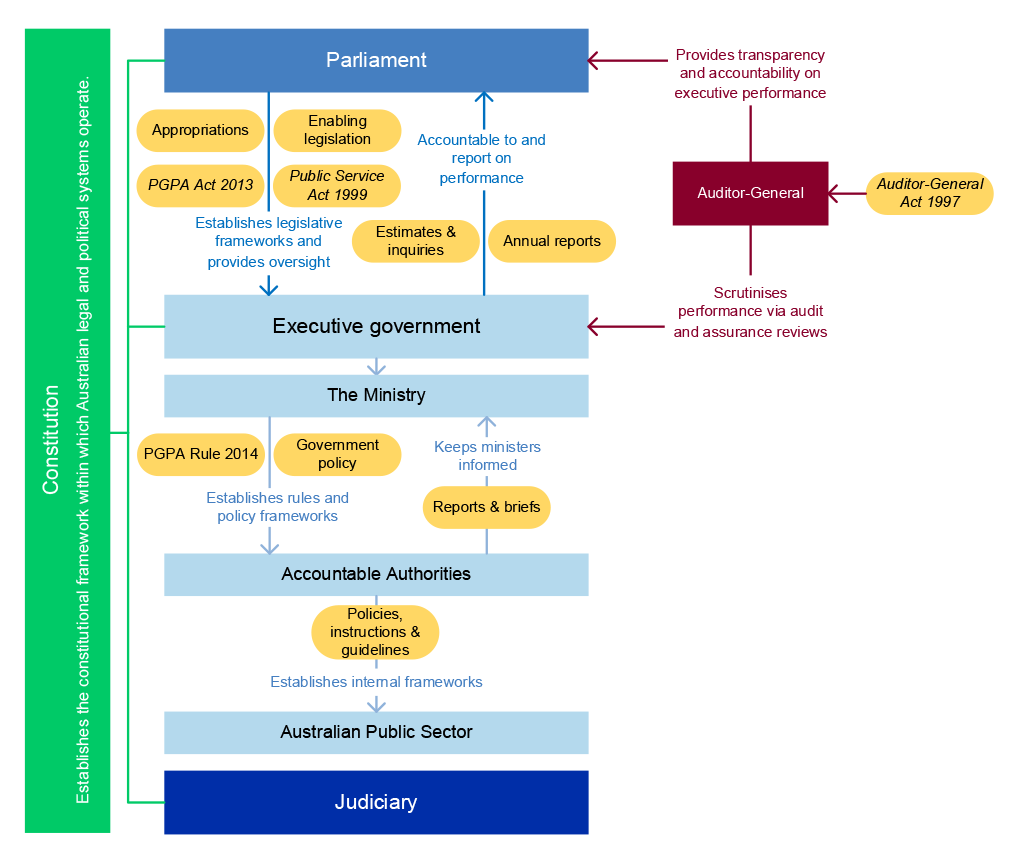

The Auditor-General provides independent assurance to the Parliament on the performance of government entities.

1.4 The Auditor-General has a unique role within the Australian public sector accountability framework (see Appendix 3), providing independent assurance on whether the executive government is operating and accounting for its performance in accordance with the Parliament’s intent.

1.5 The Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act) establishes the Auditor-General as an independent officer of the Parliament and provides that the Auditor-General has complete discretion in the exercise of audit functions or powers.5 In particular, the Auditor-General is not subject to direction from anyone in relation to: whether or not a particular audit is to be conducted; the way in which a particular audit is to be conducted; or the priority to be given to any particular matter. The Auditor-General must have regard to the audit priorities of the Parliament, as determined by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA).

1.6 The Auditor-General provides a range of audit and assurance services, including financial statements audits, performance statements audits and performance audits. Performance audits examine all or part of an entity’s operations to assess its economy, efficiency, effectiveness, ethics, and legislative and policy compliance. The Auditor-General conducts performance audits of: Commonwealth entities; Commonwealth companies and their subsidiaries; or of a Commonwealth partner.6

1.7 The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) supports the JCPAA and other parliamentary committees by providing advice and assistance in reviewing audit reports. These committees may also initiate further inquiries based on ANAO audit findings. Through this relationship, the ANAO plays a critical role in enabling the Parliament to hold government entities accountable for their use of public resources and for delivering programs and services in line with legislative and policy intent.7

Performance audit topic selection

Performance audits in 2024–25 reflected Annual Audit Work Programs and parliamentary priorities.

1.8 The ANAO identifies topics for performance audits through structured planning processes, including the development of the Annual Audit Work Program (AAWP). The AAWP is designed to ensure a broad coverage of public administration while balancing strategic priorities with the ANAO’s available resources and capabilities.8 The Auditor-General must have regard to priorities of the Parliament as identified by the JCPAA. Priority consideration is given to topics requested by the Parliament, Ministers and accountable authorities throughout the year.9 The Auditor-General also considers emerging developments in the public sector and areas of public interest.

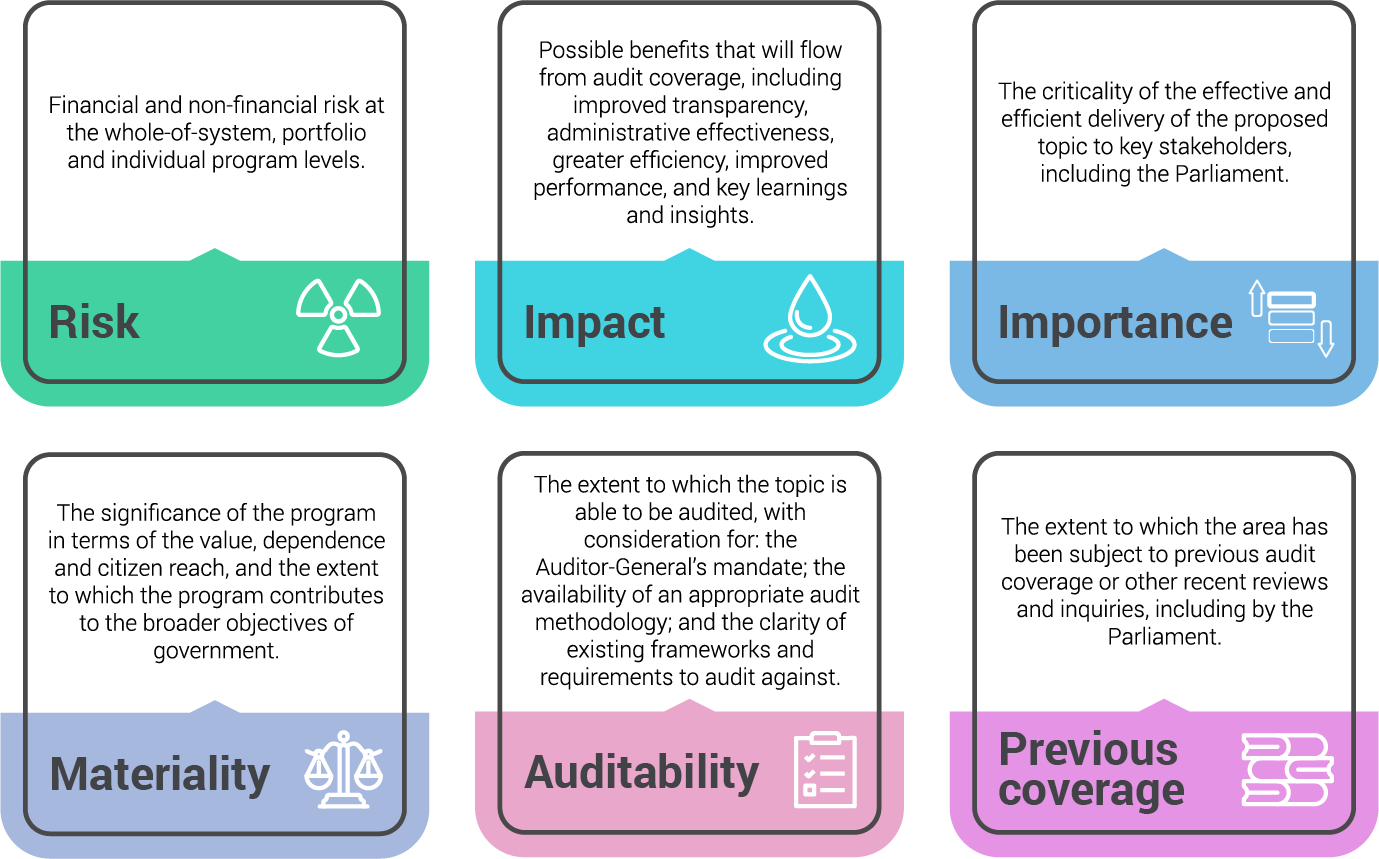

1.9 In selecting and refining performance audit topics, the Auditor-General is guided by six key considerations: risk, impact, importance, materiality, auditability and previous coverage (see Figure 1.1).10 As part of this process, the most suitable audit approach is determined, whether though a performance audit, financial statements audit, performance statements audit or other approaches.

Figure 1.1: Key considerations in the selection of a performance audit

Source: ANAO, Insights: Audit Procedure Performance Audit Process, ANAO, Canberra, November 2024, available from https://www.anao.gov.au/work/insights/performance-audit-process [accessed 28 July 2025].

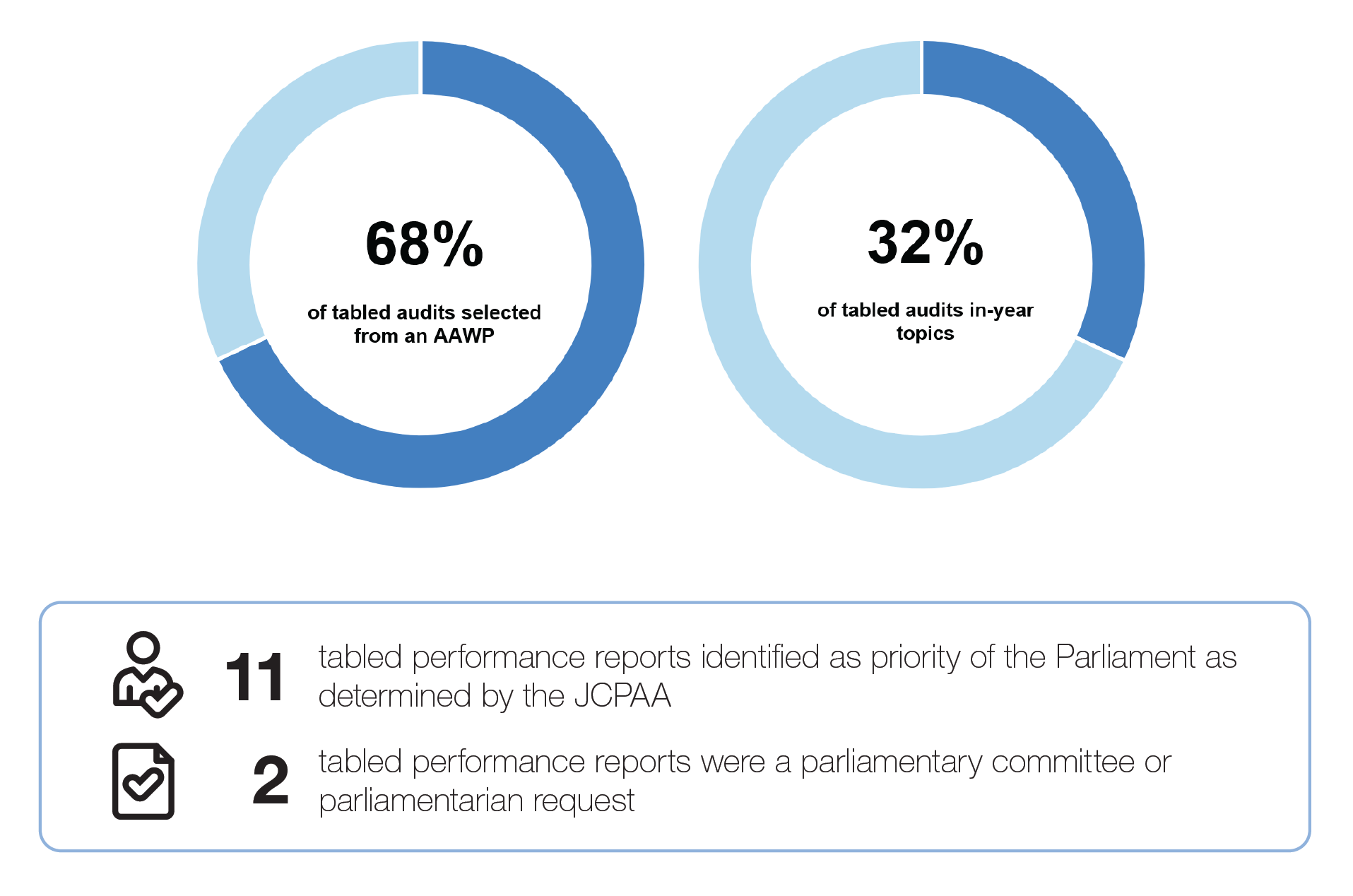

1.10 Performance audits undertaken in 2024–25 included topics drawn from both the 2023–24 and 2024–25 AAWPs.11 In 2024–25, 11 of the 44 performance audits tabled in the Parliament were audit priorities of the Parliament determined by the JCPAA. A further two were requested by either a parliamentary committee or a parliamentarian (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: 2024–25 performance audits selection, including requests of the JCPAA, other parliamentary committees, or parliamentarians

Source: ANAO analysis.

Undertaking the 2024–25 performance audits

1.11 Independence and quality are fundamental to the work of the ANAO. These principles underpin the trust placed in the Auditor-General and the ANAO by the Parliament and, by extension, the Australian public. They ensure that the ANAO delivers audits that are accurate, objective and credible, reinforcing confidence in the performance and accountability of Australian Government entities.

Access to information

Information-gathering powers are supported by confidentiality provisions.

1.12 The Auditor-General has broad information-gathering powers (see Appendix 4).12 While these powers are available to ensure the reliability of audit reports, the Auditor-General’s preferred approach is to obtain information through cooperative engagement with audited entities, using formal powers only when necessary.

1.13 For the 2024–25 performance audits tabled in the Parliament, the ANAO applied its information-gathering and access provisions under sections 32 and 33 of the Act on 11 occasions (see Appendix 4).

- Section 32 of the Act:13

- Seven notices were issued by the Auditor-General to four entities (the Department of Health, Disability and Ageing14; the National Disability Insurance Agency; the National Reconstruction Fund Corporation; and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade).

- One notice issued to a service provider (KPMG Forensic).

- Section 33 of the Act15 — three instances were used to access information from two entities (Department of Defence and Services Australia).

1.14 The Auditor-General used information-gathering powers in these circumstances to avoid doubt, or resolve potential breaches of other secrecy or privacy legislative provisions (including but not limited to the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013, or the Privacy Act 1988).

1.15 Poor recordkeeping in entities can delay auditing processes in addition to compromising good public administration and decision-making. The ANAO uses e-Discovery tools to sort through records collected as audit evidence. A key deficiency in entities is storage of records in appropriate systems. Equally, finalising draft documents and keeping complete records remains an area for ongoing diligence.

1.16 The Auditor-General’s information-gathering powers are balanced by strict confidentiality provisions. The Auditor-General is exempt from the Freedom of Information Act 1982. ANAO officials are prohibited from disclosing audit information except when performing an Auditor-General function. Draft and proposed audit reports provided to accountable authorities and persons with a special interest are subject to confidentiality requirements under subsection 36(3) of the Act.16 These documents, and any extracts, must be safeguarded at all times and may not be shared with external parties, including legal advisers, contractors, consultants, or ministers, without the written consent of the Auditor-General.

1.17 Performance audit reports draw findings and conclusions from an extensive evidence base not limited by confidentiality nor sensitivity of information. Evidence is confirmed with relevant entities through both iterative and formal processes. Adherence to confidentiality requirements is a key part of the ANAO’s process — building trust and confidence in the sector, and for the Parliament and public. Reporting on sensitive matters requires consideration of section 37 of the Act, which obliges the Auditor-General to form an opinion whether it is contrary to the public interest for sensitive information to be disclosed.

1.18 Subsection 37(1) of the Act also enables the Attorney-General to issue a certificate to the Auditor-General stating that in the opinion of the Attorney-General, disclosure of particular information would be contrary to the public interest for any of the reasons set out in subsection 37(2). In 2024–25, no certificates were issued by the Attorney-General under subsection 37(1).

Performance audit quality

ANAO’s quality framework ensures reliable audits, including through external oversight.

1.19 The ANAO’s quality framework and plan17 articulate the system of quality management that the ANAO has established to support the delivery of high-quality audit work, and enables the Auditor-General to have confidence in the opinions and conclusions in the reports prepared for the Parliament.

1.20 Auditing standards18 established by the Auditor-General under section 24 of the Act require sufficient and appropriate audit evidence to support conclusions. This process is designed to reduce the risk of forming an incorrect conclusion to an acceptable low level, thereby safeguarding the integrity of audit outcomes. External oversight of quality at the ANAO is provided through scrutiny from the Parliament, peer review arrangements with the Office of the Auditor-General New Zealand, and audits conducted by the Independent Auditor.19,20

Audit conclusions

1.21 The ANAO’s performance audits can include four types of audit conclusions assessing the effectiveness of public sector programs, systems and processes: unqualified (fully effective); largely effective; partly effective; and adverse (not effective). Audit conclusions are independent judgements that consider a range of factors including the quality of audit evidence, risk considerations and the extent to which intended objectives are met. In this report, ‘unqualified (fully effective)’ and ‘largely effective’ conclusions are considered ‘positive’ conclusions while ‘partly effective’ and ‘adverse (not effective)’ conclusions are considered ‘negative’ conclusions.

For further information

- Insights: Audit Practice Performance Audit Process — explains ANAO methodologies for officials within government entities responsible for governance, internal audit or a government activity that may be the subject of an ANAO performance audit.

Audit work during caretaker period

The ANAO continues its audit programs during the caretaker period.

1.22 During 2024–25, the ANAO continued undertaking its audit programs during the caretaker period for the 2025 Federal election. The ANAO tabled performance audit reports out of session in the Senate, as permitted by Senate Standing Order 166 (except in the case of prorogation of the Parliament due to a double dissolution). These reports were presented to the House of Representatives on 23 July 2025.

Impact of performance audits

The ANAO maintained strong engagement with the Parliament and audited entities.

1.23 Performance audits are conducted objectively and independently, free from external influence. This enables the ANAO to deliver credible, evidence-based reporting that identifies risks and shares insights to support meaningful improvements in public administration, often in ways not achievable through internal reviews or other oversight mechanisms. During 2024–25, performance audits took approximately 11 months with an average cost of $571,000.

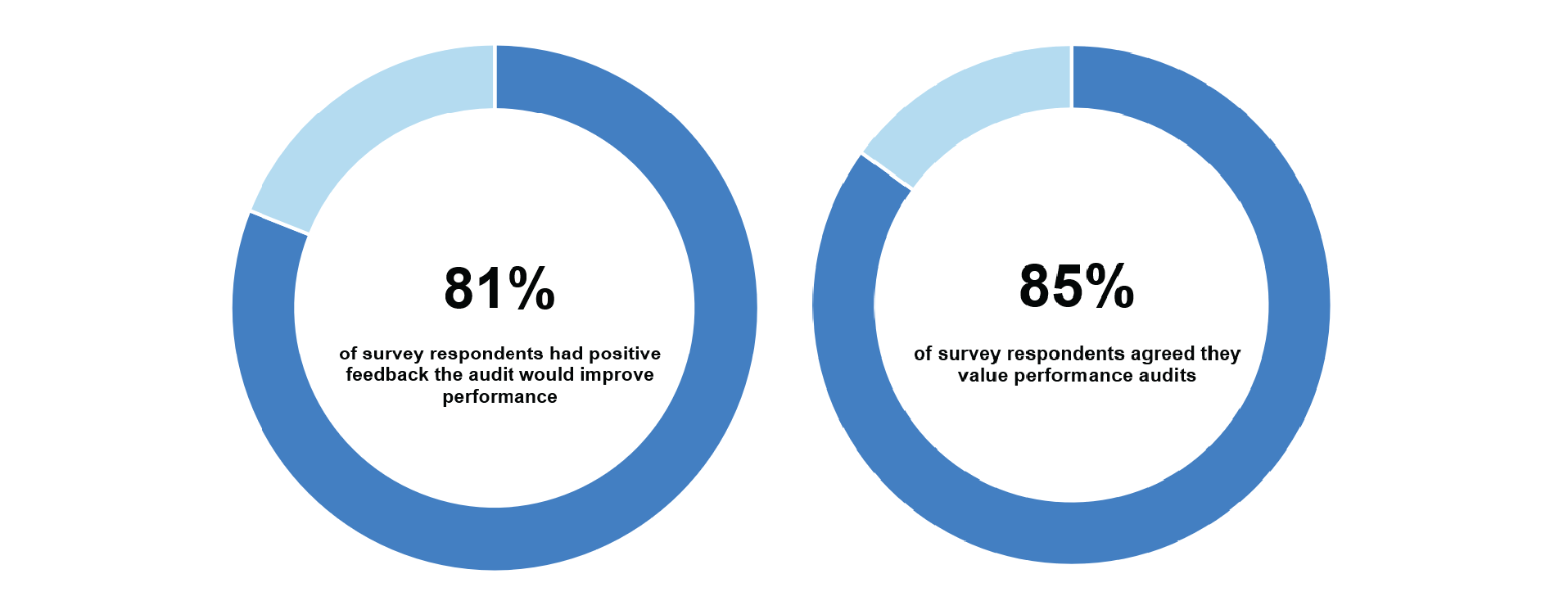

1.24 In 2024–25, the ANAO maintained strong engagement with audited entities. A high proportion of audits observed improvements during the process, with entities demonstrating a high level of acceptance of audit recommendations. Improvements observed during audits are summarised in an appendix in each performance audit report — an approach implemented at the suggestion of the JCPAA. Feedback collected through a survey of audited entities reflected positive perceptions of the impact and value of ANAO performance audits.21 Figure 1.3 provides an overview of audited entities’ view of the value and impact of ANAO performance audits in 2024–25.

Figure 1.3: Audited entities view of the value and impact of ANAO performance audits, 2024–25

Source: ANAO analysis.

1.25 The ANAO places a high value on feedback from audited entities to continuously refine its audit processes. In the 2024–25 survey, 36 out of 47 entities (77 per cent) described the audit process as a valuable contribution to their operations. Respondents also provided constructive suggestions to improve scope clarity, improve timing, and ensure greater consistency across audit teams. Figure 1.4 provides an overview of the percentage of audits which observed an improvement over the course of the audit and the responses to recommendations.

Figure 1.4: Improvements observed and responses to recommendations for ANAO performance audits, 2024–25

Source: ANAO analysis.

1.26 All performance audit reports are tabled in the Parliament and are considered parliamentary products, reinforcing transparency and enabling broad scrutiny. The ANAO’s direct and independent relationship with the Parliament, particularly through the JCPAA, is central to its role in strengthening public sector accountability and performance. The JCPAA supports this role by reviewing audit reports, conducting inquiries including public hearings, and following up on recommendations to drive improvements in public administration. In 2024–25, the JCPAA completed four inquiries relating to 24 ANAO performance audits. Key details are outlined in Figure 1.5.

Figure 1.5: ANAO support to the Parliament in 2024–25 for the performance audit program

Source: ANAO analysis.

1.27 Performance audit work plays a vital role in fostering improvement across the public sector by sharing lessons learned, insights, and examples of good practice. These contributions encourage new thinking and promote more effective ways of working.

1.28 The Auditor-General’s performance audit reports, supported by the ongoing engagement with the Parliament and public sector entities, have driven system-level improvements across government. These include legislative amendments, updates to public sector frameworks (such as the Commonwealth Procurement Rules), and enhancements to guidance materials. Case Study 1 provides a summary of key changes that were also informed by inquiries from the JCPAA.

Case study 1. Impact of audits on whole-of-government frameworks

Amendments to the Commonwealth Procurement Rules

In July 2024, the Australian Government released updated changes to the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). A summary of changes published by the Department of Finance (Finance) identifies that 22 per cent of these changes were directly influenced by ANAO performance audits or were implemented in response to audit work.a

An additional nine per cent of changes to the CPRs were the result of a JCPAA inquiryb into five performance audits, which examined procurement practices across various Commonwealth entities.

Amendments to whole-of-sector guidance on contract management

The JCPAA initiated an inquiry into the contract management frameworks used by Commonwealth entities prompted by findings from the five ANAO performance audits.c

The Committee examined ‘whether the expertise, governance arrangements, record keeping, performance measures, and policies and guidelines supporting contract management by various Commonwealth entities are fit for purpose to ensure project delivery’.d

In March 2025, the JCPAA concluded its inquiry and issued six recommendations, including a key recommendation for Finance to produce more effective guidance addressing identified weaknesses in contract management practices.d e

Note a: These were:

Recommendation no. 1 in Auditor-General Report No. 19 2022–23 Procurement Complaints Handling; and

Recommendation no. 6 in Auditor-General Report No. 21 2023–24 Management of the Australian War Memorial’s Development Project.

ANAO reports are available from https://www.anao.gov.au/pubs.

Note b: JCPAA, Parliament of Australia, Report 498: ‘Commitment issues’ - An inquiry into Commonwealth procurement, Canberra, 2025, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Public_Accounts_and_Audit/CommonwealthProcurement/Report [accessed 18 August 2025], p. xvii.

Note c: The five audits were:

Auditor-General Report No. 21 2023–24 Management of the Australian War Memorial’s Development Project;

Auditor-General Report No. 36 2023–24 Procurement of My Health Record;

Auditor-General Report No. 37 2023–24 Administration of the Adult Migrant English Program contracts;

Auditor-General Report No. 47 2023–24 Defence’s management of contracts for the supply of munitions: Part 1; and

Auditor-General Report No. 1 2024–25 Defence’s Procurement and Implementation of the myClearance System.

ANAO reports are available from https://www.anao.gov.au/pubs.

Note d: JCPAA, Parliament of Australia, Report 511: Inquiry into the contract management frameworks operated by Commonwealth entities, Canberra, 2025, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Public_Accounts_and_Audit/~/link.aspx?_id=702D6F4143B24514A999022B657EC3BE&_z=z [accessed 18 August 2025], pp. xii and xv.

Note e: For the relevant contract management guidance produced by Finance, see Department of Finance, Contract Management Guide, Canberra, 2023, https://www.finance.gov.au/government/procurement/contract-management-guide [accessed 18 August 2025].

1.29 Another example of impact of ANAO’s performance audits included revisions taking effect in October 2024 to the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines now known as Commonwealth Grants Rules and Principles, and the Commonwealth Contracting Suite changes incorporated integrity, probity and ethics matters raised by the ANAO.

2. Key themes from performance audits

2.1 The Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO’s) performance audit program is designed to deliver impact where it matters, focusing on areas of significant risk, matters of public interest, cross-entity or system-wide issues, and achievement of value for money. Within this context, performance audits provide a unique opportunity to identify and share insights across the entire Australian Government sector. These insights assist entities to identify opportunities for improvements, highlight lessons learned, and inspire new thinking and better ways of working.

2.2 Drawing on the outcomes of the 2024–25 performance audits the ANAO has identified four key themes that reflect some of the foundational elements of good public administration (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: Key themes from 2024–25 performance audits

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2024–25 performance audits.

Integrity

Public sector resource management frameworks are in place to deal with risk. Not following them exposes entities and the sector to risk and can be an indicator of a culture where compliance with rules and their intent is not respected.

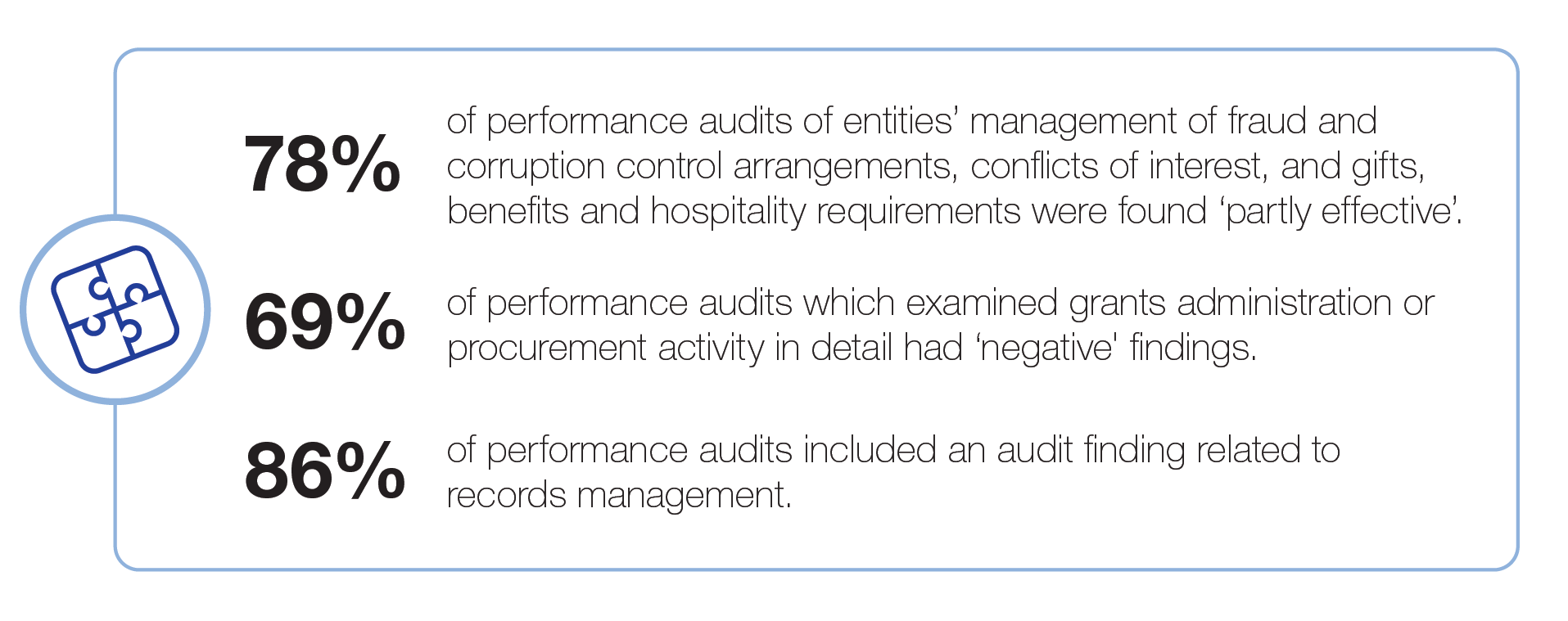

2.3 One of the recurring themes in ANAO performance audit findings and recommendations is integrity, particularly in relation to ‘getting the basics right’ by adhering to applicable policies, frameworks and laws. Performance audits often identify that integrity issues arise in areas of public administration already governed by clear and well-established legislative and policy frameworks. These include the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule), the Public Service Act 1999, Archives Act 1983, and relevant enabling legislation. Figure 2.2 outlines key information on integrity in the 2024–25 performance audits.

Figure 2.2: Integrity in the 2024–25 performance audits

Source: ANAO analysis of 2024–25 performance audits.

2.4 In 2024–25, nine performance audits examined how entities managed key integrity-related responsibilities, including fraud and corruption control arrangements, conflict of interest, and gifts, benefits and hospitality requirements. These are key areas that underpin a strong integrity culture in the public sector.22 Of the nine audits, two made ‘positive’ conclusions, while seven contained ‘negative’ conclusions.23 These audits identified instances where integrity arrangements were either not established or not effectively managed by entities. This included occasions where senior public officials were not meeting established requirements. Strong leadership is critical, including senior executives leading by example and setting the tone from the top, modelling ethical behaviour and clearly defining what is acceptable conduct within their organisations. Case study 2 provides examples of good practice and areas for improvement on integrity arrangements and controls.

Case study 2. Integrity arrangements and controlsa

Performance audits identified the importance of establishing integrity arrangements and managing them effectively. Examples include:

In Report No. 7 Fraud Control Arrangements in the Department of Health and Aged Care:

In Report No. 47 Management of Senior Executive Service Conflict of Interest Requirement:

Key: Area for improvement.

Note a: To read more, see:

Auditor-General Report No. 7 2024–25 Fraud Control Arrangements in the Department of Health and Aged Care, paragraphs 10, 2.31 to 2.32, 2.35 and 2.45; and

Auditor-General Report No. 47 2024–25 Management of Senior Executive Service Conflict of Interest Requirements, p. 42 grey box.

ANAO reports are available from https://www.anao.gov.au/pubs.

2.5 Between 2020–21 and 2024–25, 55 per cent of grants administration audits and 45 per cent of procurement activity audits resulted in ‘negative’ conclusions. This trend continued in 2024–25, with nine out of the 13 performance audits examining grants administration or procurement activity (including contract management) identifying ‘negative’ conclusions.24 These performance audits identified failures to comply with well-established rules and a lack of adherence to the intent of those rules — particularly in relation to the management of probity, transparency and competition in procurement processes.25 Case study 3 provides examples of good practice and areas for improvement on integrity in grants administration and procurement activities.

Case study 3. Integrity in grants administration and procurement activitiesa

Performance audits identified the importance of complying with well-established rules and adherence to the intent of those rules. Examples include:

In Report No. 11 Procurement by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade through its Australian Passport Office:

In Report No. 13 Implementation and Award of Funding for the Growing Regions Program:

In Report No. 37 Administration of the Future Fit Program:

Key: Good practice Area for improvement.

Note a: To read more, see:

Auditor-General Report No. 11 2024–25 Procurement by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade through its Australian Passport Office, blue box p. 19, paragraphs 3.61 to 3.64 and 3.72 to 3.74;

Auditor-General Report No. 13 2024–25 Implementation and Award of Funding for the Growing Regions Program, paragraphs 3.1 to 3.22; and

Auditor-General Report No. 37 2024–25 Administration of the Future Fit Program, p. 45.

ANAO reports are available from https://www.anao.gov.au/pubs.

2.6 Performance audit findings over time suggest a high tolerance for non-compliance when speed of delivery or output decisions are prioritised. This mindset could lead to short-term gains at the expense of long-term effectiveness and public trust.

2.7 Appropriate management of records is a persistent issue across the public sector. In 2024–25, 86 per cent of performance audits tabled in the Parliament of Australia (Parliament) included at least one finding related to inadequate records management. Furthermore, 24 Auditor-General recommendations across 17 performance audits address records management deficiencies. Effective records management is not only a legal requirement, it is essential for maintaining reliable evidence to support sound decision-making, responsive service delivery, and accountability to both the Parliament and the public. Case study 4 provides examples of areas for improvement in record keeping.

Case study 4. Record keepinga

Weaknesses in the management of records is a persistent issue across the public sector. Examples include:

In Report No. 32 Delivery of the Biosecurity Workforce:

In No. 37 Administration of the Future Fit Program:

In No. 44 Conduct of Procurements Relating to Two New Child Sexual Abuse-related National Services:

Key: Area for improvement.

Note a: To read more, see:

Auditor-General Report No. 32 2024–25 Delivery of the Biosecurity Workforce, p. 70 blue box;

Auditor-General Report No. 37 2024–25 Administration of the Future Fit Program, paragraph 3.67; and

Auditor-General Report No. 44 2024–25 Conduct of Procurements Relating to Two New Child Sexual Abuse-related National Services, paragraph 3.69.

ANAO reports are available from https://www.anao.gov.au/pubs.

For further information

- Insights: Audit Lessons Management of Conflicts of Interest in Procurement Activity and Grants Programs — summarises key messages on the management of conflict of interest in Australian government entities in relation to procurement and grants programs.

- Insights: Audit Lessons Procurement and Contract Management — eight lessons for effectively conducting Australian Government procurements.

- Insights: Audit Lessons Probity Management: Lessons from Audits of Financial Regulators — seven lessons for managing probity in an Australian Government entity.

- Insights: Audit Lessons Grants Administration — eight lessons aimed at improving grants administration across the five stages of the grants lifecycle.

- Insights: Audit Lessons Gifts, Benefits and Hospitality — seven lessons aimed at improving Australian Government entities’ compliance with gifts, benefits and hospitality requirements.

- Insights: Audit Lessons Records Management — eight lessons on improving records management practices in Australian Government entities.

Stewardship

Taking a long-term view and looking to the impact of policies and programs is an area for improvement.

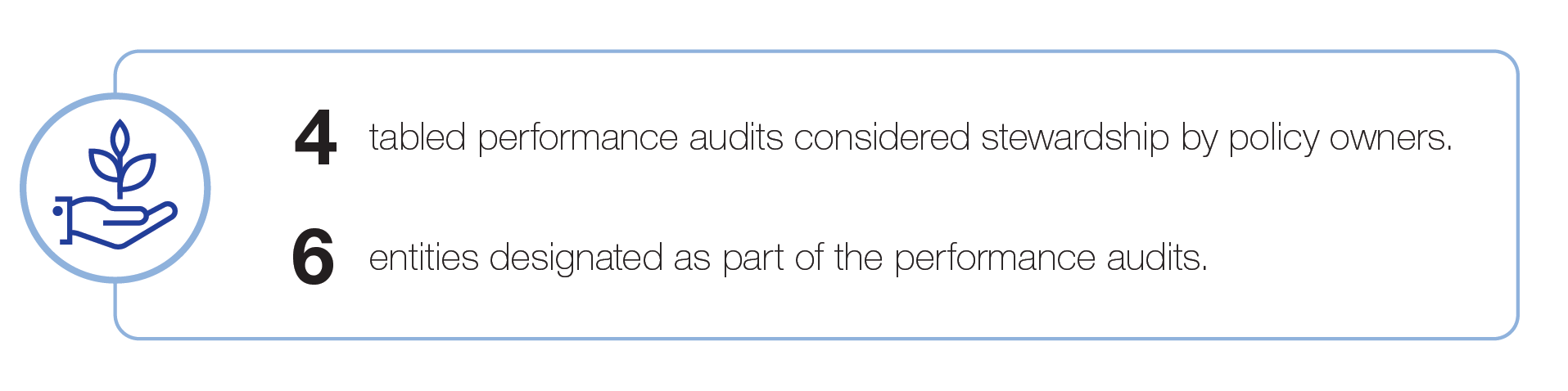

2.8 The Public Service Amendment Act 2024 introduced a new Australian Public Service (APS) value: stewardship.26 This value requires all APS employees to uphold the principle that the ‘APS builds its capability and institutional knowledge and supports the public interest now and into the future, by understanding the long-term impacts of what it does’.27 Figure 2.3 presents key information on stewardship drawn from the 2024–25 performance audits.

Figure 2.3: Stewardship in the 2024–25 performance audits

Source: ANAO analysis of 2024–25 performance audits.

2.9 Stewardship was assessed in four performance audits focused on policy owners, with three being assessed as having ‘positive’ conclusions. As stewards, policy owners need to ensure whole-of-government frameworks are not only effective today but remain fit for purpose into the future.28 These audits highlighted how entities monitor policy implementation and assess whether policies are effective in achieving their intended outcomes. Case Study 5 provides examples of good practice and areas for improvement on stewardship by policy owners.

Case study 5. Stewardship by policy ownersa

It is important that policy owners take a long-term view and consider the impact of policies and programs. Examples include:

In Report No. 29 Australian Government Advertising: November 2021 to November 2024:

In Report No. 33 Administration of the Impact Analysis Framework:

In Report No. 34 Treasury’s Design and Implementation of the Measuring What Matters Framework:

In Report No. 38 Ministerial Statements of Expectations and Responding Statements of Intent:

Key: Good practice Area for improvement.

Note a: To read more, see:

Auditor-General Report No. 29 2024–25 Australian Government Advertising: November 2021 to November 2024, p. 28 blue box;

Auditor-General Report No. 33 2024–25 Administration of the Impact Analysis Framework, p. 67 blue box;

Auditor-General Report No. 34 2024–25 Treasury’s Design and Implementation of the Measuring What Matters Framework, paragraph 3.40; and

Auditor-General Report No. 38 2024–25 Ministerial Statements of Expectations and Responding Statements of Intent, paragraphs 10 and 1.10.

ANAO reports are available from https://www.anao.gov.au/pubs.

2.10 In 2024–25, ANAO performance audits also examined how entities are achieving current outcomes while also maintaining focus on the long-term by considering whether entities are equipped to adapt to future challenges and whether their decisions avoid introducing or elevating long-term risks. Examples include: arrangements supporting the adoption of new technologies; asset management practices across the full life cycle; and frameworks designed to respond to future events and evolving service delivery needs. Case Study 6 provides examples of good practice and areas for improvement on stewardship for the long term.

Case study 6. Stewardship for the long terma

Performance audits identified the importance of achieving current outcomes with a long-term view. Examples include:

In Report No. 5 Australian Government Crisis Management Framework:

In Report No. 21 Bureau of Meteorology’s Management of Assets in its Observing Network:

In Report No. 50 Department of Defence’s Sustainment of Canberra Class Amphibious Assault Ships (Landing Helicopter Dock):

Key: Good practice Area for improvement.

Note a: To read more, see:

Auditor-General Report No. 5 2024–25 Australian Government Crisis Management Framework, p. 45 blue box;

Auditor-General Report No. 21 2024–25 Bureau of Meteorology’s Management of Assets in its Observing Network, paragraph 11, p. 44 blue box and p. 45 grey box; and

Auditor-General Report No. 50 2024–25 Department of Defence’s Sustainment of Canberra Class Amphibious Assault Ships (Landing Helicopter Dock), paragraph 4.46.

ANAO reports are available from https://www.anao.gov.au/pubs.

2.11 Stewardship is fundamental to sustaining long-term capability of the APS. Insights from ANAO performance audits prompt important reflection on whether the public service is adequately positioned to uphold this long-term focus, particularly as the sector navigates rapid technological advancements and an increasingly complex external environment. Key ANAO observations on aspects of policy stewardship are outlined in Box 1.

Box 1: ANAO observations on key aspects of stewardship by policy owners

Risk management

Actively identifying and managing risk sets entities up for success in complex environments.

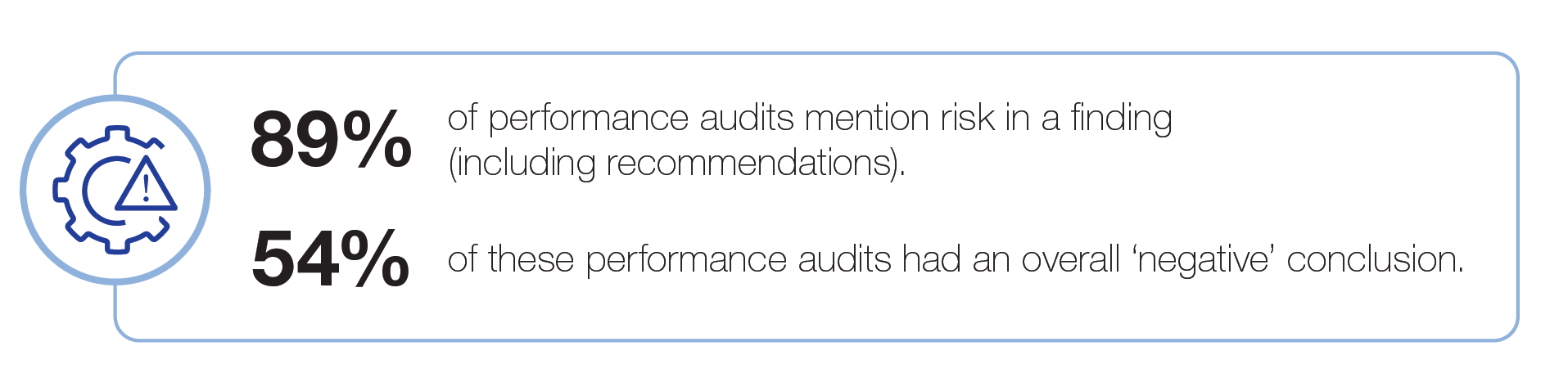

2.12 Risk is inherent in all government activities. The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy seeks ‘to embed risk management into the culture and work practices of [Australian Government] entities to improve decision making in order to maximise opportunities and better manage uncertainty’.29

2.13 Given the diversity and complexity of risks faced by the public sector, ANAO performance audits routinely assess how entities manage risk. In 2024–25, 89 per cent of tabled performance audits included findings or recommendations related to risk management. This is further outlined in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4: Risk management in the 2024–25 performance audits

Source: ANAO analysis of 2024–25 performance audits.

2.14 A theme across these performance audits is the presence of deficiencies in entities’ risk management practices. Many entities have not fully embedded risk management into their organisational culture or day-to-day operations. Common gaps include: failure to establish effective risk management frameworks or policies; lack of regular review and updating of controls for relevance and effectiveness; and limited visibility and coordination across different risk management activities, including poor alignment with enterprise-level risks and defined risk appetites. Case Study 7 provides examples of good practice and areas for improvement on risk management practices in the public sector.

Case study 7. Risk management practicesa

Performance audits identified the importance of actively identifying and managing risks. Examples include:

In Report No. 19 Administration of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme:

In Report No. 41 Effectiveness of the Board of the National Disability Insurance Agency:

In Report No. 42 Management and Oversight of Compliance Activities within the Child Care Subsidy Program:

Key: Good practice Area for improvement.

Note a: To read more, see:

Auditor-General Report No. 19 2024–25 Administration of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, paragraphs 13 and 2.55 to 2.65;

Auditor-General Report No. 41 2024–25 Effectiveness of the Board of the National Disability Insurance Agency, paragraphs 25 and 3.20 to 3.47; and

Auditor-General Report No. 42 2024–25 Management and Oversight of Compliance Activities within the Child Care Subsidy Program, paragraphs 2.17 to 2.19.

ANAO reports are available from https://www.anao.gov.au/pubs.

2.15 Audit findings frequently highlight shortcomings in the implementation of risk-based approaches to regulation. In 2024–25, five performance audits examined regulatory activities, four resulted in ‘negative’ conclusions, with one assessed as having a ‘positive’ conclusion.30 Where audits identified entities were ‘partly’ effective, risk-based and data driven approaches were not central to the management of their regulatory responsibilities. A core principle of effective regulation is that actions taken by regulators31 should be proportionate to the risk being managed. Without a robust risk-based approach, regulators are less equipped to encourage compliance, deter non-compliance and deliver consistent, fair, and effective regulatory outcomes. Despite these challenges, ANAO performance audits also identified examples of good practices, such as: establishing effective risk arrangements; management of shared risks; and the integration of risk information into advice provided to government. Case Study 8 provides an example of area for improvement on management of risk by regulators.

Case study 8. Risk management by regulatorsa

Performance audits identified shortcomings in the implementation of risk-based approaches to regulation. An example includes:

In Report No. 27 Sport Integrity Australia’s Management of the National Anti-Doping Scheme:

Key: Area for improvement.

Note a: To read more, see:

Auditor-General Report No. 27 2024–25 Sport Integrity Australia’s Management of the National Anti-Doping Scheme, paragraphs 2.38 to 2.39 and p. 39 blue box.

ANAO reports are available from https://www.anao.gov.au/pubs.

2.16 ANAO audit activity continues to highlight the importance of ensuring public sector entities fully meet expectations set out in the Commonwealth Risk Management policy.32 This includes establishing the fundamentals of risk management33; embedding risk based considerations into decision-making processes; and maintaining ongoing monitoring and review of risks. Effective risk management should be a core feature of all government activity and be tailored to the context in which it operates.

For further information

- Insights: Audit Lessons Risk Management — eight lessons aimed at improving risk management practice.

- Insights: Audit Lessons Administering Regulations — five key learnings on the administration of regulation.

Performance management

Measuring performance enables adjustment, improvement and transparency.

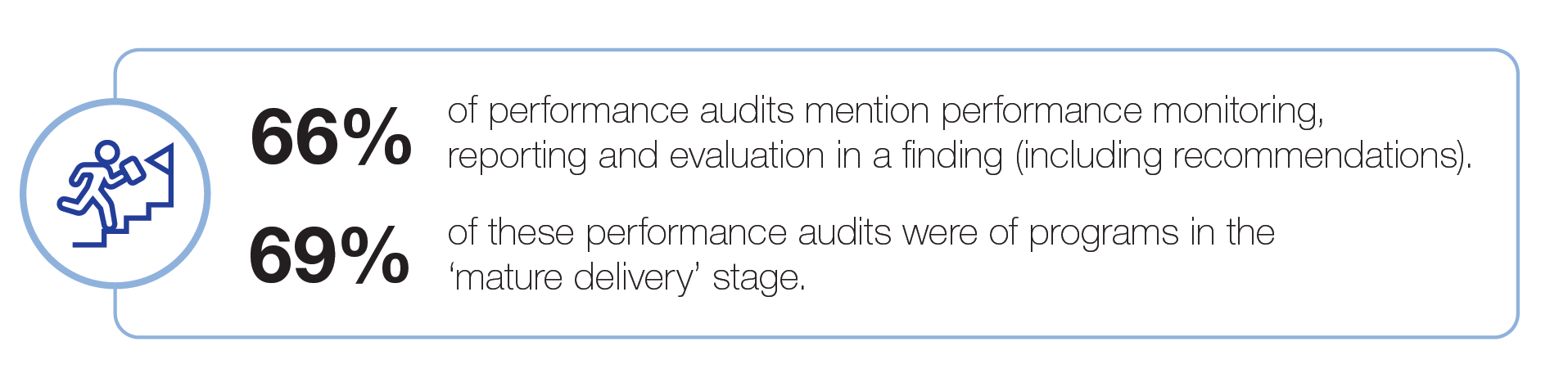

2.17 Performance information, including how it is measured, reported, and used to demonstrate whether public funds are making a difference and delivering on government objectives, is a central focus of the PGPA Act. In 2024–25, 29 of the 44 performance audits (66 per cent) included findings or recommendations related to performance monitoring, reporting or evaluation.34 This is outlined in Figure 2.5. While these audits identified examples of good practice in the sector, they also identified that entities fall short in effectively measuring and reporting on performance at the project, program and entity level.

Figure 2.5: Performance management in the 2024–25 performance audits

Source: ANAO analysis of 2024–25 performance audits.

2.18 A key risk emerging from audit findings is that entities have not yet consistently established robust systems for measuring and reporting program performance. This is notable, given that 69 per cent of the audits were related to programs in the ‘mature delivery’ stage. Common issues included incomplete or inadequate performance information and a lack of reporting on program outcomes, which limits an entity’s ability to assess whether objectives are being met or what change might need to be made to program delivery to better achieve the outcome. Case study 9 provides examples of good practice and areas for improvement on performance monitoring and reporting in the public sector.

Case study 9. Performance monitoring and reportinga

Performance audits identified the importance of monitoring and reporting in assessing the achievement of objectives or improving outcomes. Examples include:

In Report No. 19 Administration of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme:

In Report No. 27 Sport Integrity Australia’s Management of the National Anti-Doping Scheme:

In Report No. 28 Management of Complaints by the Australian Taxation Office:

Key: Good practice Area for improvement.

Note a: To read more, see:

Auditor-General Report No. 19 2024–25 Administration of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, paragraph 2.42;

Auditor-General Report No. 27 2024–25 Sport Integrity Australia’s Management of the National Anti-Doping Scheme, paragraphs 2.12 and 2.14; and

Auditor-General Report No. 28 2024–25 Management of Complaints by the Australian Taxation Office, paragraphs 3.10 and 3.11.

ANAO reports are available from https://www.anao.gov.au/pubs.

2.19 These issues also extend to contract management and supplier performance. Performance audits identified that entities often failed to ensure compliance with contractual requirements or verify that deliverables were met as intended.35 Without effective performance monitoring and reporting, entities cannot reliably assure that they, or contractors acting on behalf of the Commonwealth, have delivered the intended outcomes. Case study 10 provides examples of good practice and areas for improvement on contract management and supplier performance.

Case study 10. Contract management and supplier performancea

Performance audits identified the importance of ensuring compliance with contractual requirements and verifying that deliverables were met as intended. Examples include:

In Report No. 18 Procurement and Contract Management by Tourism Australia:

In Report No. 46 Management of the OneSKY Contract:

In Report No. 50 Department of Defence’s Sustainment of Canberra Class Amphibious Assault Ships (Landing Helicopter Dock):

Key: Good practice Area for improvement.

Note a: To read more, see:

Auditor-General Report No. 18 2024–25 Procurement and Contract Management by Tourism Australia, paragraphs 3.27, 3.35 and p. 63 grey box;

Auditor-General Report No. 46 2024–25 Management of the OneSKY Contract, paragraphs 1.15 to 1.16; and

Auditor-General Report No. 50 2024–25 Department of Defence’s Sustainment of Canberra Class Amphibious Assault Ships (Landing Helicopter Dock) p. 57 grey box.

ANAO reports are available from https://www.anao.gov.au/pubs.

2.20 Evaluation continues to be a recurring area of concern, with seven reports identifying instances where evaluations were: not planned early or at all; not implemented or conducted regularly; or were unable to accurately measure the program’s impact on its intended policy objectives. Case study 11 provides opportunities for improvement on evaluation of programs and initiatives.

Case study 11. Evaluation of programs and initiativesa

Performance audits identified evaluation of programs and initiatives continues to be an area of concern in public administration. Examples include:

In Report No. 26 Governance of Artificial Intelligence at the Australian Taxation Office:

In Report No. 42 Management and Oversight of Compliance Activities within the Child Care Subsidy Program:

Key: Area for improvement.

Note a: To read more, see:

Auditor-General Report No. 26 2024–25 Governance of Artificial Intelligence at the Australian Taxation Office, paragraph 11; and

Auditor-General Report No. 42 2024–25 Management and Oversight of Compliance Activities within the Child Care Subsidy Program, paragraph 2.59.

ANAO reports are available from https://www.anao.gov.au/pubs.

2.21 The ANAO is in the fourth full year of audits of performance statements. Over the past four years, the ANAO has observed stronger compliance with legal requirements and greater reliability of measures. In entities with repeat audits, the ANAO observes fewer findings and growing maturity of performance measurement systems, including improved governance and established and empowered central performance teams. Notwithstanding the important progress that has been made, the ANAO is yet to consistently see entities shift from a compliance to a performance and accountability approach through our performance statements audit work. Audits point to many lessons, among which are the need for a greater emphasis on meaningful reporting, outcomes, impact, efficiency and linking reporting to decision-making through enterprise performance systems.

2.22 Observing performance, understanding what drives it, and making decisions to improve it are essential to achieving outcomes, and is important for transparency and accountability in delivery. Implementing improvements in performance management — whether by addressing deficiencies, scaling successful approaches or discontinuing ineffective ones — will help lift public sector productivity. The ANAO’s performance audit and performance statements work highlights that good performance monitoring and evaluation is a maturing area of public sector capability. Performance management needs to be applied across all aspects of public sector activity, and equally important at the ‘early delivery’ and ‘mature delivery’ stages of a program or policy.

For further information

- Insights: Audit Opinion Using Performance Information to Drive Effectiveness — Commonwealth Performance Framework and how it can be better used to drive effectiveness in the Australian public sector. This includes the need to prioritise the improvement of performance frameworks, embed a performance culture and use performance information to drive business improvement.

- Insights: Audit Lessons Reporting Meaningful Performance Information — six key areas within the framework where lessons can support entities prepare useful and high-quality performance statements.

- Insights: Audit Lessons Performance Measurement and Monitoring — Developing Performance Measures and Tracking Progress — five key areas of performance information, monitoring and evaluation learnings.

3. Performance audit analysis

3.1 This chapter presents an analysis of performance audits tabled by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) over a five-year period, from 2020–21 to 2024–25. It provides insights into the public sector’s performance across a range of metrics captured through audit activity, highlighting both areas of strength and opportunities for improvement. For the purposes of this analysis, audited entities were grouped by portfolio in accordance with the ANAO’s 2025–26 Annual Audit Work Program (AAWP) portfolio classification.36

Performance audit program, 2020–21 to 2024–25

44 performance audits tabled in 2024–25.

3.2 Between 2020–21 and 2024–25, the ANAO tabled 211 performance audits, with 44 audits tabled in 2024–25. Figure 3.1 outlines the high-level details from the performance audits tabled in the Parliament of Australia (Parliament) between 2020–21 and 2024–25.

Figure 3.1: Performance audit program, 2020–21 to 2024–25a

Note a: This analysis reflects the number of discrete entities at time of audit publication.

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits between 2020–21 and 2024–25.

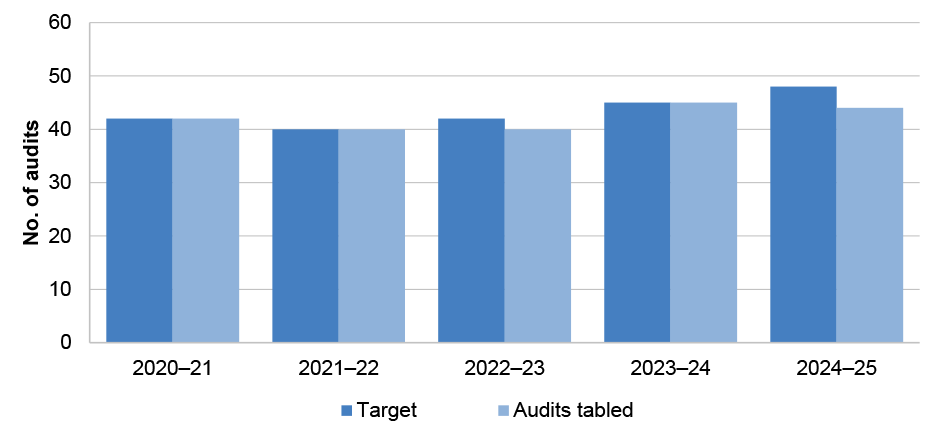

3.3 Figure 3.2 outlines the number of performance audits tabled in the Parliament compared to the target as outlined in the ANAO’s 2024–25 Portfolio Budget Statement and Corporate Plan.37

Figure 3.2: Number of performance audits tabled compared to performance target, 2020–21 to 2024–25a

Note a: In 2020–21, 42 audits and 41 reports were tabled in the Parliament. Auditor-General Report No. 11 2020–21, Indigenous Advancement Strategy — Children and Schooling Program and Safety and Wellbeing Program was completed as two separate audits but was tabled as a single report.

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits between 2020–21 and 2024–25.

3.4 The ANAO met its performance audit report targets in 2020–21, 2021–22 and 2023–24, demonstrating consistent delivery against planned audit activity. However, as outlined in the ANAO’s 2025–26 Portfolio Budget Statements, the target of 48 performance audits for 2024–25 was not achieved with 44 audits tabled by year-end. During 2024–25, the ANAO acted to right-size its work within the budget available and this involved targeting the ANAO’s available resources to the areas of highest priority, which impacted the ANAO’s ability to deliver the target for performance audits.

Analysis of audit coverage of the public sector

Audit coverage of the public sector is informed by budget commitments, responsibilities and risks.

3.5 The Auditor-General has the authority to conduct performance audits of: Commonwealth entities; Commonwealth companies and their subsidiaries; or a Commonwealth partner. Audits of Commonwealth partners that are part of, or controlled by, state or territory governments must be requested by the responsible minister or the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA). Similarly, performance audits of government business enterprises can be conducted only if requested by the JCPAA.38 Section 17 of the Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act) enables the Auditor-General to propose that the JCPAA make such a request.

3.6 The ANAO aims to deliver a balanced performance audit program that is informed by risk and designed to promote accountability, transparency and improvements to public administration. The number of audits conducted within each portfolio or entity type reflects a range of considerations during the audit selection process, including: risk, impact, importance, materiality, auditability and previous coverage (see paragraph 1.9).

3.7 Between 2020–21 and 2024–25, the four portfolios with the highest number of performance audits tabled were: Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts (34 audits); Home Affairs (28 audits); Defence (26 audits); and Health, Disability and Ageing (26 audits). The distribution reflects the complexity, scale, and strategic importance of these portfolios.

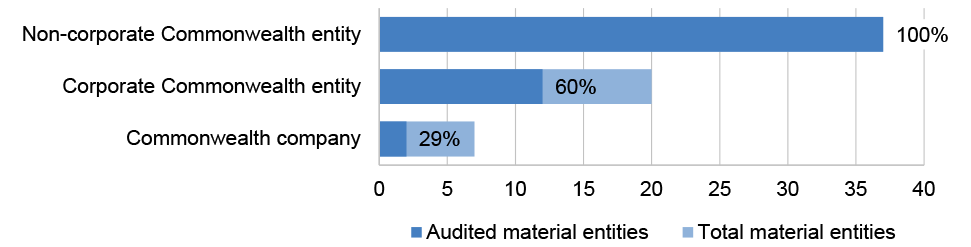

3.8 Between 2020–21 and 2024–25, performance audit coverage of material government entities are outlined below. Material entities39 are defined as government entities whose total financial income, expenses, assets and liabilities fall within the top 99 per cent of the total general government sector, including all departments of state (see Figure 3.3).40

Figure 3.3: Audit coverage of material entities by type of entity, 2020–21 to 2024–25

Source: ANAO analysis of audited entities between 2020–21 and 2024–25 against the Australian Government Organisation Register, as at 29 May 2025.

Performance audits on matters relating to Indigenous Australians

16 performance audits related to Indigenous matters between 2020–21 and 2024–25.

3.9 As part of the performance audit program, the Auditor-General undertakes audits that focus specifically on Australian government policies and programs affecting Indigenous Australians. In doing so, the ANAO is committed to undertaking performance audits that are culturally respectful, transparent, and inclusive of Indigenous Australians’ perspectives and circumstances. The ANAO is developing its approach to audits on Indigenous matters and aims to ensure that performance audit teams undertake cultural capability training and engage with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stakeholders, including traditional owners, Indigenous organisations and governance bodies including, at times, in-community and on country. This engagement allows for firsthand insights into the effectiveness of systems and process of organisations and programs which seek to achieve outcomes for First Nations people.

3.10 In 2024–25, the Auditor-General tabled four performance audit reports whose audit objective specifically related to Indigenous matters. These audits examined areas such as: fraud control arrangements; implementation of recommendations; management of conflicts of interest in entities responsible for Indigenous matters; and ‘mandatory minimum requirements’ targets for minimum Indigenous employment and/or supply use for certain Australian Government contracts in other entities required to operate within frameworks established to support First Nations peoples.

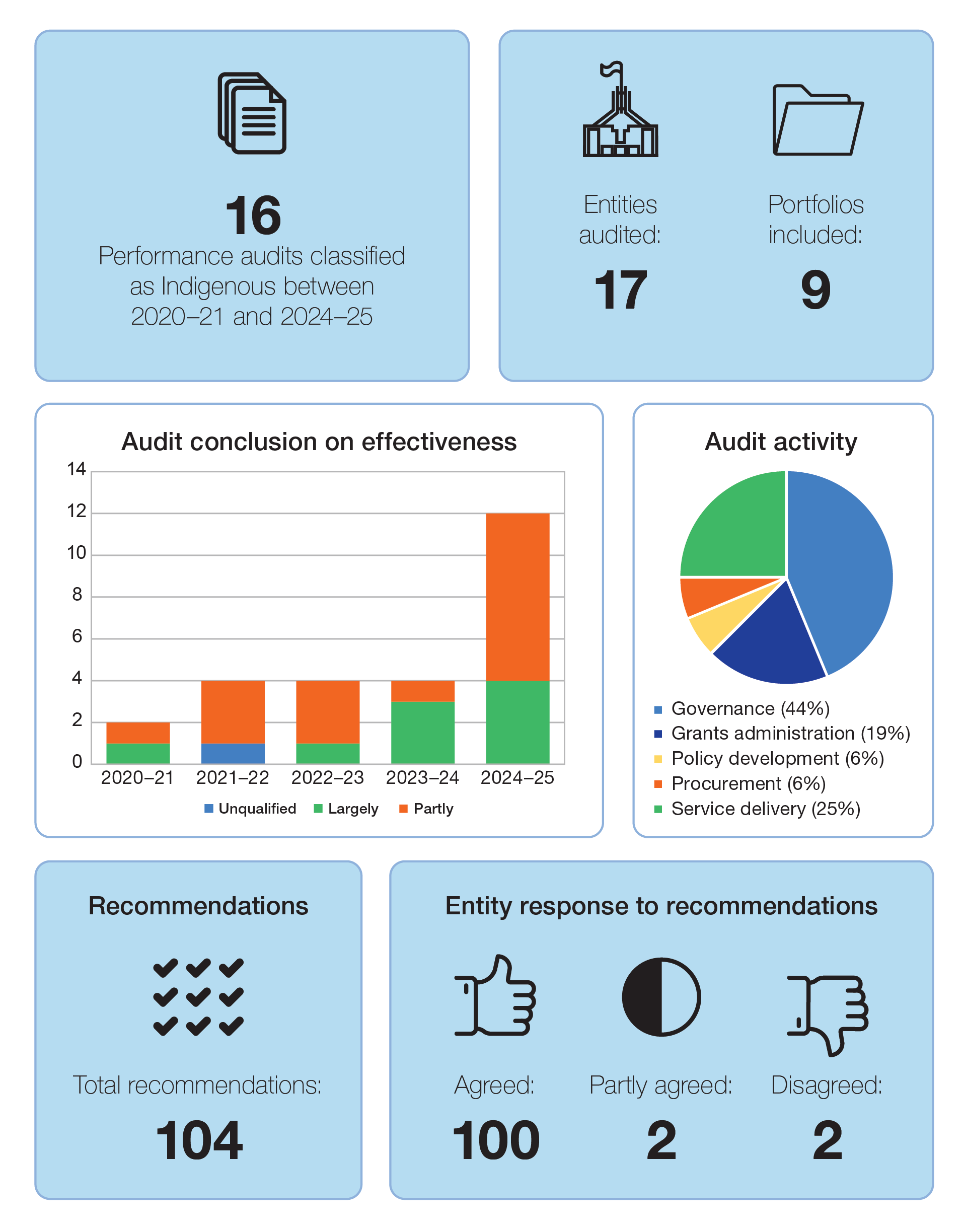

3.11 Between 2020–21 and 2024–25, 16 performance audits have been tabled whose audit objective specifically related to Indigenous matters.41 The performance audits involved 17 entities across nine portfolios, with 104 recommendations made.42 Figure 3.4 provides an overview of the performance audits classified as ‘Indigenous’ over the five-year period.

Figure 3.4: Performance audits classified as Indigenous, 2020–21 to 2024–25

Source: ANAO analysis of Indigenous themed performance audits from 2020–21 and 2024–25.

3.12 The ANAO’s audit program also extends to cover Indigenous matters where they intersect with broader areas of public administration. A further eight performance audits included substantive analysis of Indigenous related matters between 2020–21 and 2024–25. The audits covered a range of activities including Indigenous health outcomes, vaccination and immunisation programs, schemes to promote access to education and employment initiatives.

Analysis by audit conclusion

Over the past five years, 54 per cent of audit conclusions have been assessed as ‘positive’.

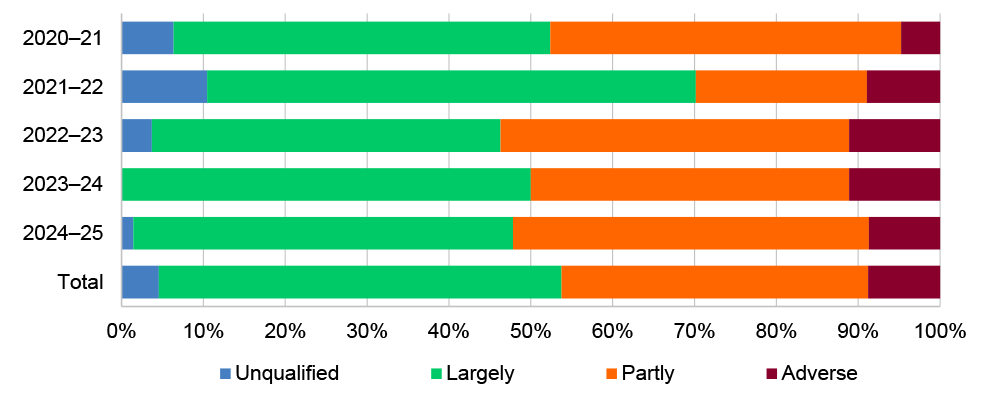

3.13 Between 2020–21 and 2024–25, 54 per cent of audit conclusions have been assessed as ‘positive’, indicating that entities were either unqualified (fully effective) or largely effective in delivering outcomes and complying with relevant frameworks.43 Figure 3.5 outlines the percentage distribution of the audit conclusions for the audits tabled between 2020–21 and 2024–25.

Figure 3.5: Audit conclusions, 2020–21 to 2024–25a

Note a: Between 2020–21 and 2021–22, COVID-19 audits focused on identifying risks and lessons for public sector entities amid rapid implementation of government initiatives. Three of four audits tabled in December 2020 focused on key messages for entities to consider in managing related risks and challenges.

Source: ANAO analysis of audit conclusions by audited entities in audits tabled from 2020–21 to 2024–25.

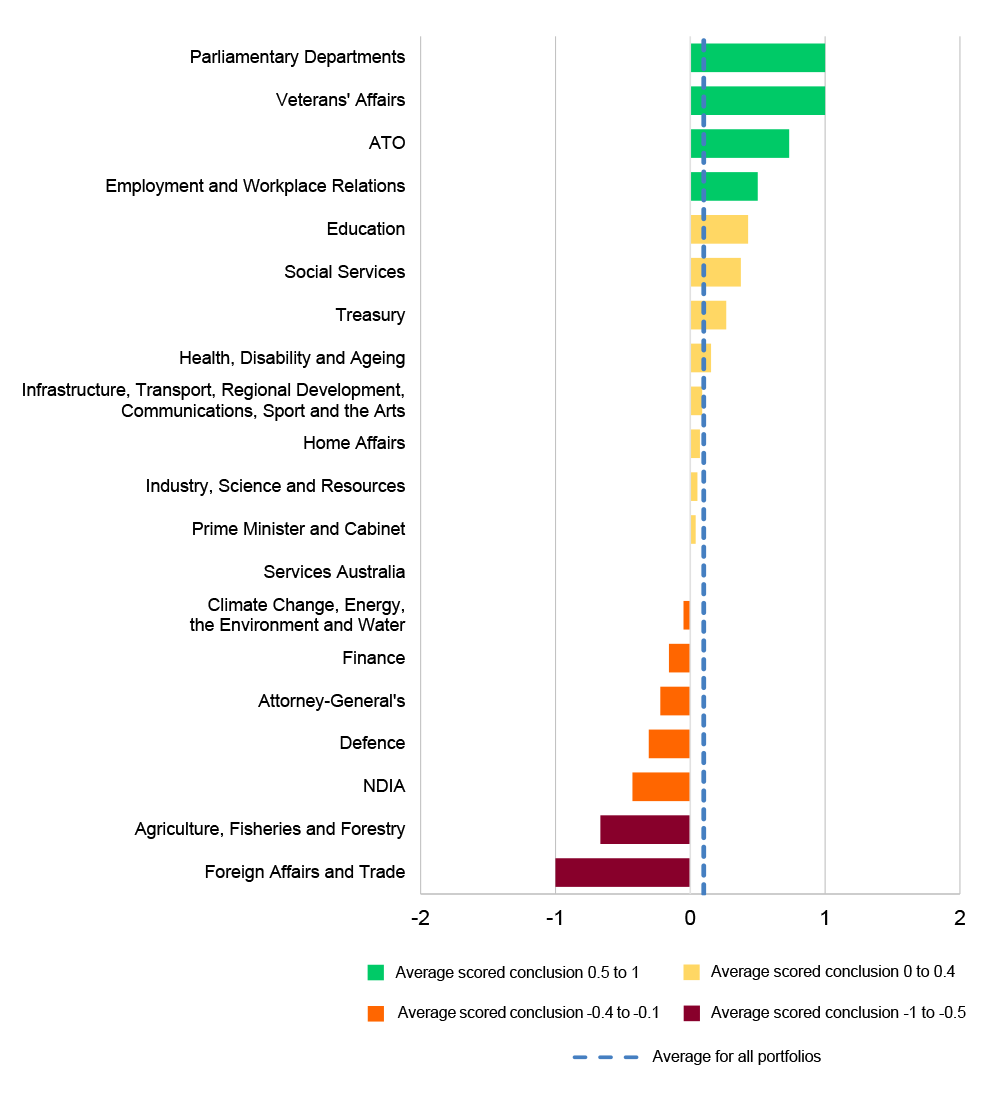

3.14 Figure 3.6 outlines the average score based on audit conclusions: ‘adverse’ (-2); ‘partly’ (-1); ‘largely’ (1); and ‘unqualified’ (2). Scores are calculated by tallying all audit conclusions per entity between 2020–21 and 2024–25 and averaging the result for the portfolio.

3.15 The portfolios with the lowest average score are the Foreign Affairs and Trade portfolio (-1), and the Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry portfolio (-0.7). The highest average scores are with the Parliamentary Departments and Veterans’ Affairs (1); noting, Parliamentary Departments only had one audit.

Figure 3.6: Average audit conclusion score, 2020–21 to 2024–25a, b

Note a: The average score is calculated based on the following rules: ‘adverse’ (-2); ‘partly’ (-1); ‘largely’ (1); and ‘unqualified’ (2). The average score across all portfolios is around 0.1.

Note b: Two audited non-governmental entities are excluded from this figure.

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits tabled between 2020–21 and 2024–25.

Analysis by audit objective

Opportunities exist to consider efficiencies when delivering government programs or priorities, especially in the context of service delivery functions.

3.16 Subsection 15(1) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requires the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity to govern the entity in a way that promotes the proper use and management of public resources. The PGPA Act defines ‘proper’ as efficient, effective, economical and ethical (see paragraph 1.1 and footnote 1). Entities also must comply with relevant legislative requirements, and for non-corporate Commonwealth entities, operate in a way that is not inconsistent with the policies of the Australian Government.44

3.17 In line with these obligations, each ANAO performance audit includes an assessment of whether the entity has implemented the audited program or activity in a way that meets one or more of the PGPA Act’s core principles — efficiency, effectiveness, economy, and ethics. Table 3.1 outlines the percentage of audits against each of the four objectives for 2020–21 to 2024–25 (211 performance audits) and 2024–25 (44 performance audits).

Table 3.1: Audit coverage by objective, 2020–21 to 2024–25 and 2024–25a

|

Audit objective |

2020–21 to 2024–25 (%) |

2024–25 (%) |

|

Effectiveness |

73.9 |

61.4 |

|

Economy |

11.8 |

15.9 |

|

Ethics |

11.4 |

20.5 |

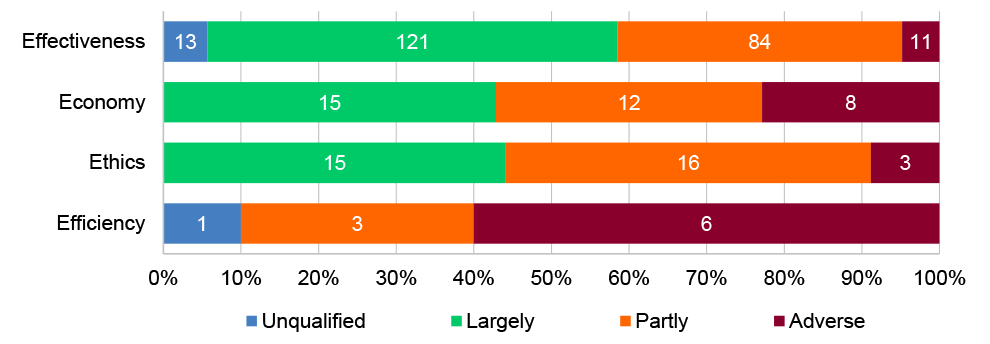

|

Efficiency |

2.8 |

2.3 |

Note a: Percentages may not total 100 per cent due to rounding.

Source: ANAO analysis of audit objectives between 2020–21 and 2024–25.

3.18 As outlined in Figure 3.7, between 2020–21 and 2024–25 performance audits assessing effectiveness had the highest proportion of ‘positive’ conclusions (59 per cent) and audits assessing efficiency had the highest proportion of ‘negative’ conclusions (90 per cent).

Figure 3.7: Audit objectives by audit conclusions per entity, 2020–21 to 2024–25

Source: ANAO analysis of audit objectives against audit conclusions for each entity from 2020–21 to 2024–25.

3.19 Performance statement audits also examine efficiency in public sector operations.45 While the Commonwealth Performance Framework aims to achieve a balance between outputs, efficiency and effectiveness measures, ANAO audits of selected Australian Government entities’ performance statements have consistently noted that ‘There is currently limited reporting by entities of efficiency (inputs over outputs) and even less reporting of both efficiency and effectiveness for individual key activities.’46 Efficiency or proxy efficiency targets accounted for 15 per cent of all targets in the 2023–24 performance statements audits.47

3.20 Each performance audit is guided by a clearly defined audit objective, which focuses on an aspect of an entity’s operations.48 This objective is determined by the Auditor-General and communicated to the entity and relevant parties at the outset of a performance audit. Between 2020–21 and 2024–25, audits focused on efficiency have predominantly examined government service delivery, with audits focused on economy largely concentrated on procurement activities. Figure 3.8 outlines the distribution of audit objective by audit activity, highlighting the areas of focus across the ANAO’s performance audit program.

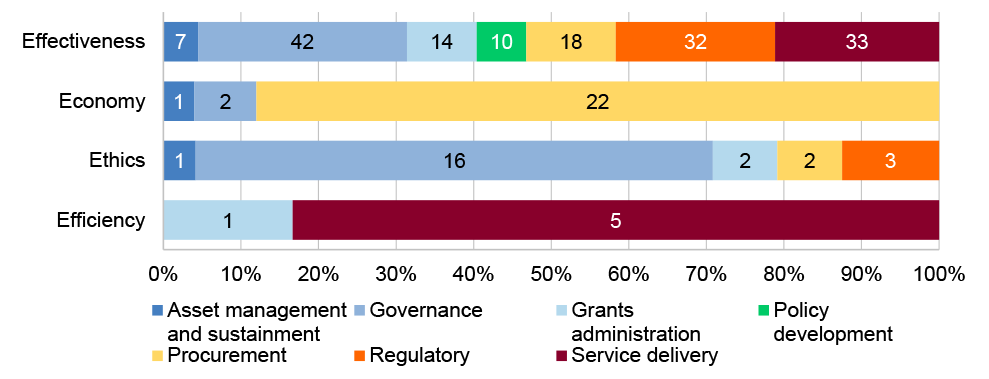

Figure 3.8: Audit objective by audit activity, 2020–21 to 2024–25

Source: ANAO analysis of audit objectives against audit activity between 2020–21 and 2024–25.

Analysis by activity

Entities generally demonstrate strong capability in policy development. Grants administration and procurement are areas for attention to improve performance across the public sector.

3.21 All ANAO performance audits assess one of seven key public administration activities, referred to as the ‘audit activity’. The performance audit program is designed to deliver a balanced mix of audits across these activities.

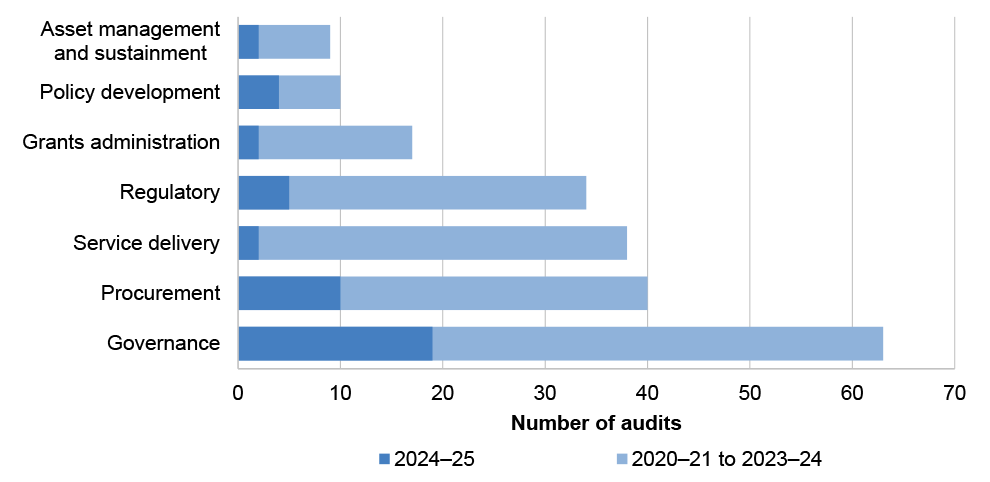

3.22 Between 2020–21 and 2024–25, the most frequently audited activity was governance, accounting for 30 per cent of all performance audits.49 This reflects the foundational role governance plays in enabling effective public administration, as required by the PGPA Act or other legislative requirements. Procurement was the second most common audit activity accounting for 19 per cent of all performance audits, while asset management and sustainment was the least audited activity area. Figure 3.9 outlines the distribution of audits by activity over the five-year period.

Figure 3.9: Audits by activity tabled in 2024–25 and 2020–21 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits tabled between 2020–21 and 2024–25.

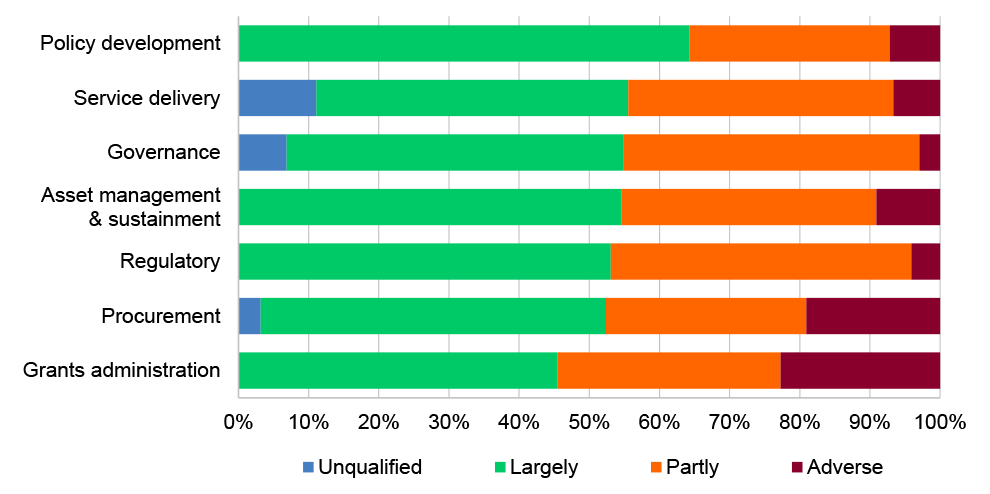

3.23 Audit conclusions vary across the seven key public administration activities, as outlined in Figure 3.10. Among the performance audits tabled between 2020–21 and 2024–25, service delivery had the highest proportion of ‘unqualified’ audits (11 per cent), indicating effectiveness. Policy development showed the strongest overall performance, with 64 per cent of audits receiving ‘positive’ conclusions (‘unqualified’ or ‘largely effective’). In contrast, grants administration and procurement recorded the highest share of ‘adverse’ conclusions, at 23 per cent and 19 per cent respectively. Notably, 55 per cent of grants administration audits resulted in ‘negative’ conclusions (e.g. ‘adverse’ or ‘partly effective’).

Figure 3.10: Audit conclusions per entity by audit activity, 2020–21 to 2024–25

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits tabled 2020–21 to 2024–25.

3.24 This analysis reinforces that while entities generally perform well in policy development, grants administration and procurement remain areas requiring improvement. Despite the existence of well-established legal and policy frameworks, performance audits continue to identify breaches of rules and non-compliance with their intent (see paragraph 2.5).

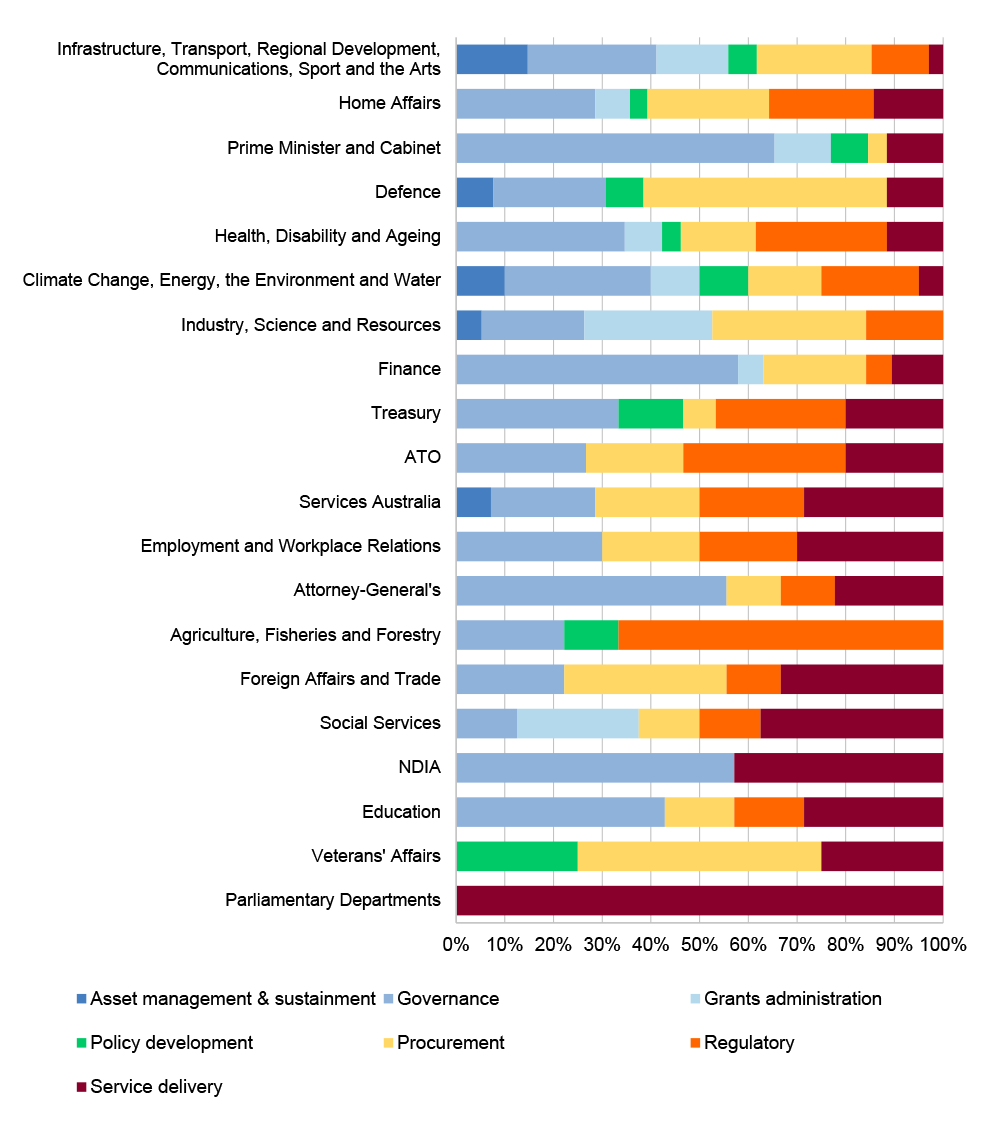

3.25 Figure 3.11 presents a breakdown of tabled performance audits across portfolios by their primary audit activity.50 The distribution of performance audits by audit activity reflects the distinct operational mandates and risk profiles of each portfolio. For example:

- Fifty per cent of tabled audits in the Defence portfolio had procurement as the primary audit activity, reflecting the Department of Defence’s ranking as the Australian Government’s largest procurer.51

- More than half of audits in the Finance and the Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolios have governance as the primary audit activity, reflecting both portfolios’ stewardship roles in the whole-of-government frameworks to achieve intended outcomes.52

3.26 The Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Sports and the Arts portfolio recorded the highest number of tabled performance audits (34 audits) across all government portfolios over the five years. Notably, this portfolio had audits covering all seven key public administration activities, reflecting the number of policy areas and the diverse entities covered by the portfolio. Forty-five per cent of audits on ‘asset management and sustainment’ were in this portfolio, reflecting its role in managing major national assets.

3.27 Figure 3.11 outlines the audit coverage by primary audit activity by portfolio, from most audited to least audited portfolio, for 2020–21 to 2024–25.

Figure 3.11: Audit activitya of tabled audits by portfoliob, 2020–21 to 2024–25

Note a: Two audited non-governmental entities are excluded from this figure.

Note b: Portfolios are as at 13 May 2025. Audits of entities that have moved portfolios as part of machinery of government changes between 2020–21 and 2024–25 are classified by their current portfolios.

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits between 2020–21 and 2024–25.

Analysis by stage of delivery

Mature delivery audits are the most common stage of delivery with 49 per cent of audit conclusions assessed as either effective or largely effective.

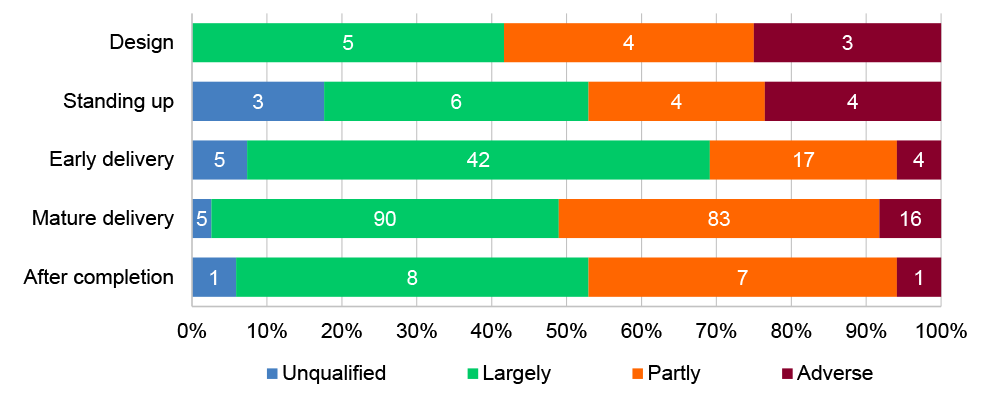

3.28 Australian Government programs and activities exhibit diverse risk profiles depending on their stage of maturity and the nature of the environment of delivery. Performance audits conducted during the design, standing up and early delivery phases provide valuable insights that can inform implementation strategies and strengthen delivery mechanisms. These early-stage audits can be useful for identifying foundational risks and opportunities for course correction. In contrast, audits of programs at the mature delivery and after completion stage are geared towards providing assurance, collecting evidence of outcomes, capturing lessons learned, and assessing whether the objectives were achieved. Figure 3.12 outlines the audit conclusion per entity by the five stages of delivery.

Figure 3.12: Audit delivery stage by audit conclusion per entity, 2020–21 to 2024–25

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits between 2020–21 and 2024–25.

3.29 Between 2020–21 and 2024–25, most portfolios were subject to audits across multiple stages of delivery. The mature delivery audits were the most frequently audited, accounting for 63 per cent of all audits. Of these, 49 per cent were assessed as having ‘positive’ conclusions, indicating a relatively high level of assurance at this stage of delivery. For conclusions assessed as ‘adverse’, these were notably higher in earlier stages: 25 per cent for programs in the design phase and 24 per cent for those in the standing up stage of delivery. These findings suggest that early stage programs are more vulnerable to implementation risks and governance challenges.

Entity responses to recommendations

Entities fully agreed to 93 per cent of all recommendations between 2020–21 and 2024–25.

3.30 Through its performance audits, the ANAO identifies opportunities for improvement and makes targeted recommendations to strengthen public sector program management and governance. These recommendations are designed to support entities in enhancing their performance, accountability, and service delivery. When an entity responds to a recommendation in a tabled audit report, it formalises a public commitment to the Parliament to implement the agreed actions.53 This response is a key mechanism for reinforcing transparency and accountability in the Australian Government sector.

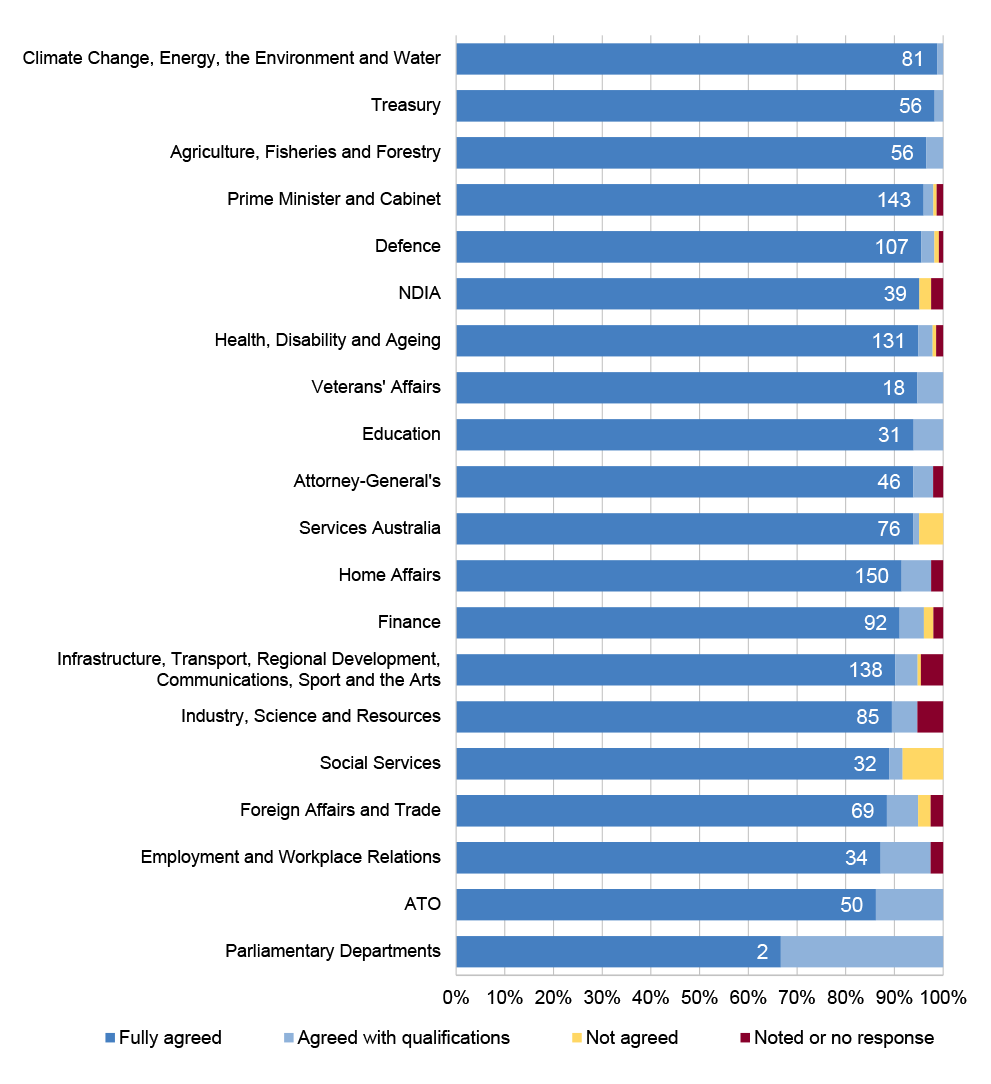

3.31 The ANAO classifies entity responses to the audit recommendations into four categories: fully agreed; agreed with qualification; noted/no response; or disagreed. Between 2020–21 and 2024–25, entities agreed in full to 93 per cent of all recommendations, demonstrating a strong level of acceptance and alignment with the ANAO findings. This high rate of agreement reflects constructive engagement between the ANAO and audited entities, and the relevance of the recommendations in improving public administration (see Figure 3.13).

Figure 3.13: Entity response to recommendations, 2020–21 to 2024–25a

Note a: Two audited non-governmental entities are excluded from this figure.

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2020–21 and 2024–25.

3.32 In 2024–25, 213 recommendations (96 per cent) were counted as ‘agreed’ (this includes three recommendations that were agreed with qualification and assessed to be ‘agreed’). Six recommendations were agreed with qualification and assessed to be ‘not agreed’ and one that was not agreed, and one was noted. Over the five year period, the portfolios with the highest number of recommendations ‘not agreed’ were Services Australia (four recommendations) and Social Services (three recommendations).

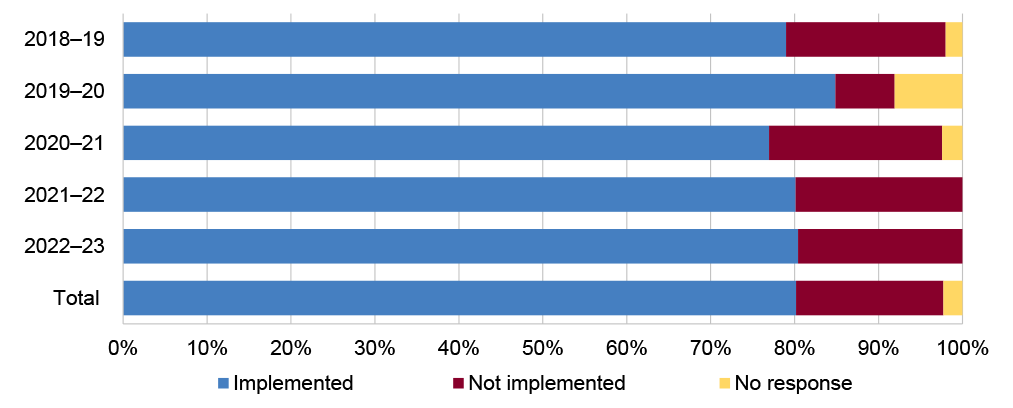

Implementation of recommendations

3.33 Implementation of recommendations is the responsibility of the accountable authority/s (or the government) to which they are made. The ANAO observes progress on the implementation of performance audit recommendations through attendance at entity audit committees, and conducts a program of performance audits to assess that progress of previous recommendations made. The ANAO requests annual advice from relevant entities, seeking updates on implementation progress of recommendations, over a 24-month period following the tabling of the audit.

3.34 To assess whether ANAO recommendations have been addressed by entities, a full 24-month implementation period is required from the time the audit recommendations are made. The 24-month period is used in recognition of the variety of recommendations made. Many recommendations require immediate attention to address risk. Some recommendations may require longer-term planning to achieve successful implementation. Between 2018–19 to 2022–23 entities self-reported that an average of 80 per cent of recommendations were implemented in this timeframe (see Figure 3.14).54

Figure 3.14: Implementation of recommendations within 24 months, 2018–19 to 2022–23a

Note a: Where a recommendation addresses multiple entities, it is considered ‘implemented’ if the majority of entities have reported implementing the recommendation.

Source: ANAO analysis.

3.35 The ANAO maintains an ongoing program of performance audits focused on assessing entities’ implementation of both parliamentary committee and Auditor-General recommendations.55 These audits are critical for verifying whether entities have taken meaningful action in response to audit findings. These audits have identified discrepancies between reported and actual implementation: in several cases, entities have self-reported recommendations as implemented, yet audit evidence has shown otherwise. To date, audits in this program have identified that 29 per cent of recommendations that entities had reported as implemented were assessed by the ANAO as not implemented or partly implemented.

For further information

- Insights: Audit Insights Implementation of Recommendations — key observations on governance and implementation arrangements to support effective implementation of recommendations.

Appendices

Appendix 1 2024–25 tabled performance audits by portfolio

|

Audit titlea |

Entities audited |

|

Across Entity |

|

|

|

|

Ministerial Statements of Expectations and Responding Statements of Intent |

|

|

Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry portfolio |

|

|

|

|

Attorney General’s portfolio |

|

|

Management of Conflicts of Interest by the Australian Financial Security Authority |

|

|

Management of Complaints by the Australian Human Rights Commission |

|

|

Australian Government Advertising: November 2021 to November 2024b,c |

|

|

Conduct of Procurements Relating to Two New Child Sexual Abuse-related National Services |

|

|

Australian Taxation Office |

|

|

Governance of Artificial Intelligence at the Australian Taxation Office |

|

|

|

|

Australian Taxation Office’s Procurement of IT Managed Services |

|

|

Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water portfolio |

|

|

Compliance with Gifts, Benefits and Hospitality Requirements in the Murray–Darling Basin Authority |

|

|

|

|

Bureau of Meteorology’s Management of Assets in its Observing Network |

|

|

|

|

Administration of the Equipment Energy Efficiency Program (GEMS) |

|

|

Defence portfolio |

|

|

Defence’s Procurement and Implementation of the myClearance System |

|

|

|

|

Maximising Australian Industry Participation through Defence Contracting |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Education portfolio |

|

|

Management and Oversight of Compliance Activities within the Child Care Subsidy Programb |

|

|

Employment and Workplace Relations portfolio |

|

|

Fraud Control Arrangements in the Australian Skills Quality Authority |

|

|

Effectiveness of the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman’s Regulatory Functions |

|

|

Finance portfolio |

|

|

Australian Government Advertising: November 2021 to November 2024b |

|

|

Design and Establishment of the National Reconstruction Fund Corporationb |

|

|

Foreign Affairs and Trade portfolio |

|

|

Procurement by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade through its Australian Passport Office |

|

|

|

|

Management of Senior Executive Service Conflict of Interest Requirementsb |

|

|

Health, Disability and Ageingc portfolio |

|

|

Fraud Control Arrangements in the Department of Health and Aged Care |

|

|

Fraud Control Arrangements in the National Health and Medical Research Council |

|

|

Management of Conflicts of Interest by Corporate Commonwealth Entity Boardsb |

|

|

|

|

Sport Integrity Australia’s Management of the National Anti-Doping Scheme |

|

|

Australian Government Advertising: November 2021 to November 2024b |

|

|

|

|

Management of Senior Executive Service Conflict of Interest Requirementsb |

|

|

Home Affairs portfolio |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Management of Senior Executive Service Conflict of Interest Requirementsb |

|

|

Industry, Science and Resources portfolio |

|

|

Implementation and Award of Funding for the Growing Regions Programb |

|

|

Design and Establishment of the National Reconstruction Fund Corporationb |

|

|

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts portfolio |

|

|

Australian Government Commitment to the Melbourne Suburban Rail Loop East Project |

|

|

Management of Conflicts of Interest by Corporate Commonwealth Entity Boardsb |

|

|

Implementation and Award of Funding for the Growing Regions Programb |

|

|

Fraud and Corruption Control Arrangements in Creative Australia |

|

|

|

|

National Disability Insurance Agency |

|

|

Effectiveness of the Board of the National Disability Insurance Agency |

|

|

|

|

Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Services Australia |

|

|

|

|

Management and Oversight of Compliance Activities within the Child Care Subsidy Programb |

|

|

Treasury |

|

|

|

|

Treasury’s Design and Implementation of the Measuring What Matters Framework |

|

Note a: Auditor-General reports are available from https://www.anao.gov.au/pubs. Two entities are split out from their designated portfolio due to materiality and complexity: the National Disability Insurance Agency are split out from the Health, Disability and Ageing portfolio; and the Australian Taxation Office is split out from the Treasury portfolio.

Note b: There is a total of 56 audits listed. This includes 44 tabled audits plus 12 duplicate entries addressing cross-entity audits which included entities from multiple portfolios.

Note c: On the 13 May 2025, the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts changed to the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications, Sport and the Arts.

Source: Australian National Audit Office analysis of performance audit reports from 2024–25.

Appendix 2 2024–25 Insights and Audit Matters publications

1. The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) supports the work of the Australian Government by producing reports and products that provide insight into public sector performance (based on the findings within our audit programs) and understand areas for improvement in performance.

2. The ANAO publishes the following Insights reports: Audit Lessons, which aim to make it easier for the Australian public sector to apply insights from our audit; Audit Practice, which aim to explain ANAO methodologies to help entities prepare for an ANAO audit; and Audit Opinion, which aim to provide the Auditor-General’s views on key issues facing the Australian public sector.56 In 2024–25, four audit lessons and two audit practice Insights products were published.

2024–25 Insights publications

|

Gifts, Benefits and Hospitality This edition is targeted at those responsible for implementing internal policies and controls on the receipt of gifts, benefits and hospitality in Australian Government entities. |

|